I am sure that the word sharecropping brings to most folk’s minds, images of the antebellum deep South, poor Black men and women toiling away for little reward, and merciless southern landowners. But you know what, as with most things associated with slavery, from its beginnings to its aftermath, we northerners in general, and Rhode Islanders in particular, are just fooling ourselves regarding our ultimate responsibilities. We were a part of all this too; indeed, in some cases, we were the driving wheel behind the evil engine that was slavery.

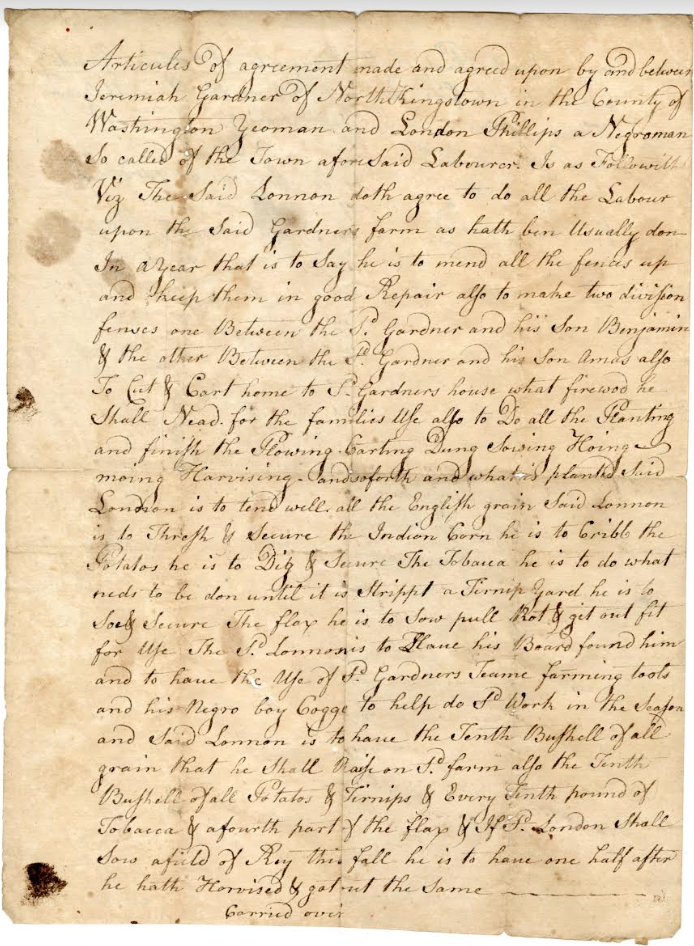

Sharecropping is a case in point. This 1783 sharecropping agreement between a local landed gentry farmer (“Yeoman” is the period correct term) Jeremiah Gardner and a freed enslaved man, Lonnon Philips, informs us an awful lot about where South County (now formerly Washington County) stood when it came to the one-sided dignity-crushing practices of sharecropping that occurred, not only in the post-Civil War era South, but in late 18th century Rhode Island too.

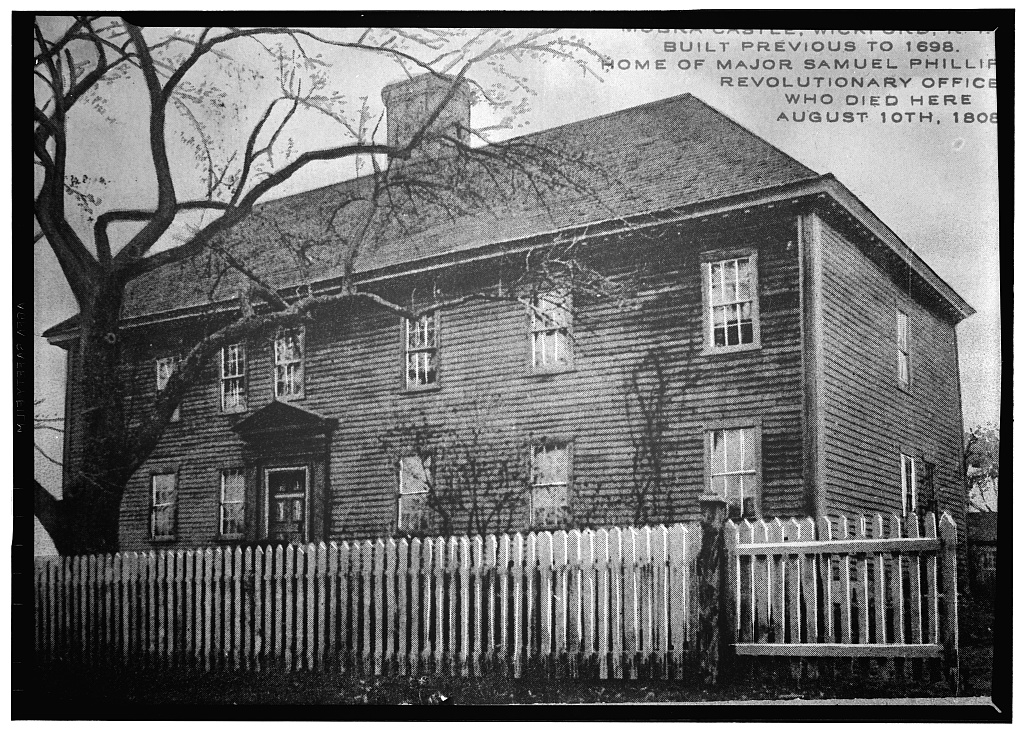

This is a postcard showing the Phillips Mansion House, known as Mowbra Castle, which was the centerpiece of the South County plantation at which Lonnon had formerly been enslaved.

The American Revolutionary War and the period afterwards did see a number of manumissions of enslaved people in Rhode Island. Or enslaved people negotiated their freedom with their masters or even freed themselves by running away. But badges of slavery continued in South County. One of them was that freed men and women were often forced into temporary work arrangements, particularly sharecropping agreements. Set forth below is an exact transcription of a sharecropping agreement that I found when reviewing the Hammond Family Papers of the South County Room Collection at the North Kingstown Free Library.

Articles of agreement made and agreed upon by and between Jeremiah Gardner of North Kingstown in the County of Washington, Yeoman, and Lonnon Philips a negroman so called of the town aforesaid, laborer. Is as followeth; Viz the said Lonnon doth agree to do all the labor upon the said Gardner’s farm as hath been usually done in a year, that is to say, he is to mend all the fences up and keep them in good repair. Also, to make two division fences, one between the said Gardner and his son Benjamin and the other between the said Gardner and his son Amos. Also, to cut & cart home to said Gardner house what firewood he shall need for the families use. Also, to do all the planting and finish the plowing and carting dung sowing, howing, mowing, harvesting and so forth and what is planted, said Lonnon is to tend well. All the English grain said Lonnon is to thresh and secure. The Indian corn he is to crib. The potatoes he is to dig and secure. The tobacco he is to do what needs to be done until it is stripped. A turnip yard he is to sow and secure. The flax he is to sow, pull out and get out fit for use. The said Lonnon is to have his board found him and to have the use of said Gardner’s team, farming tools, and his negro boy “Cogge” to help do said work in the season and said Lonnon is to have the tenth bushel of all grain that he shall raise on the farm, also the tenth bushel of all potatoes and turnips and every tenth pound of tobacco and a fourth part of the flax. If said Lonnon shall sow a field of rye this fall, he is to have one half after he hath harvested and got out the same.

Each party hath here unto set their hands and seals this first day of April in the seventh year of Independence, Anno Domino 1783. Signed sealed and delivered in presence of Wm. Hammond.

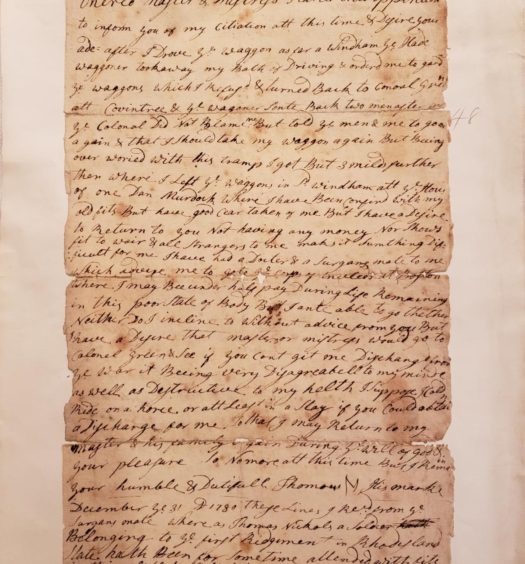

First page of the sharecropping agreement between Lonnon Philips and Jeremiah Gardner, 1783, from the North Kingstown Town Hall records

The tasks assigned to Lonnon under this agreement appear to be the ones a white master would order an enslaved man to accomplish. Lonnon has a whole raft of things he must do, many of them farming related, but also the task of continuously providing the Gardner family with firewood in an age where that was the only heat source and cooking fuel. Oh yeah, by the way, he also needs to construct two long fence lines along each side of the whole farm and keep all the existing fences and stone walls in good order. These tasks he must do before he can even begin farming to earn money for himself.

What does Lonnon get for all the non-farming work and the farming work of clearing land, planting, maintaining the crops in the ground and harvesting them? He gets room and board, probably in a small shack, outbuilding or barn. He can use Jeremiah’s team of draft animals, farm tools and an enslaved boy named Cogge. What are the fruits of his labor that Lonnon obtains? After all, the tenant’s “share” is what sharecropping agreements are all about. Lonnon’s share, for the most part, is a meager one tenth of what he raises. Meanwhile Jeremiah he sits up in the big house (which still exists to this day at 1510 Boston Neck Road) and gets the other 90% of Lonnon’s labors.

It is not clear how Lonnon acquired food to subsist until the crops had been harvested and he obtained his share. He may have had to borrow money, perhaps from Jeremiah. Then Lonnon would have been in a debt trap.

I have got to tell you all, this dash of South County reality has got me thinking about equity just about as much as the times we live in have. I am also struck by the irony built into the quite common phrasing for the time frame that describes the year 1783 – “The seventh year of Independence”. Independence for who? All men are created equal? I wonder what Lonnon thought about that on the April day when he made his mark on this sharecropper agreement?

[For a related article, see “Newport Philips: A North Kingstown Slave Negotiates his Way to Freedom,” by Tim Cranston, at https://smallstatebighistory.com/newport-philips-a-north-kingstown-slave-negotiates-his-way-to-freedom/. Lonnon may have been related to Newport Philips.]