Ever since my book, The Seventh Rhode Island Infantry in the Civil War was published by McFarland in 2008, it opened a literal floodgate of material relating to the Seventh Rhode Island. In that time my private collection has grown tremendously and I have crisscrossed the country gathering almost every scrap of paper I could find regarding the regiment. Even better, advances in technology have brought to light many new contemporary newspaper accounts on the Seventh Rhode Island. The result of all of this research has produced several file cabinets full of new and useful material that will one day be used to write an updated unit history.

Among the many resources not available to me when I wrote my book in 2006-2007 were the absolutely fantastic and vital papers of Major Thomas Fry Tobey contained within the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Covering nearly his entire life, the Tobey papers provide a great deal of material relevant to Seventh Rhode Island. Among the gems found within was a long letter that Tobey penned to his brother John F. Tobey a week after the Battle of Fredericksburg. Transcribed and edited below, this letter contains the best descriptions I have ever found regarding the Seventh Rhode Island at Fredericksburg.[1]

Thomas Fry Tobey was the son of Dr. Samuel Boyd Tobey and Sarah Earl Fry Tobey. He was born in Providence on September 30, 1840. The Tobey family members were “eminent Quakers,” and Thomas took part in the faith growing up. He graduated from Brown University in 1859; among his acquaintances was John Hay, private secretary to Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and later United States Secretary of State. Thomas graduated from Harvard Law School in 1861 and went into the practice of law with his brother John F. Tobey.[2]

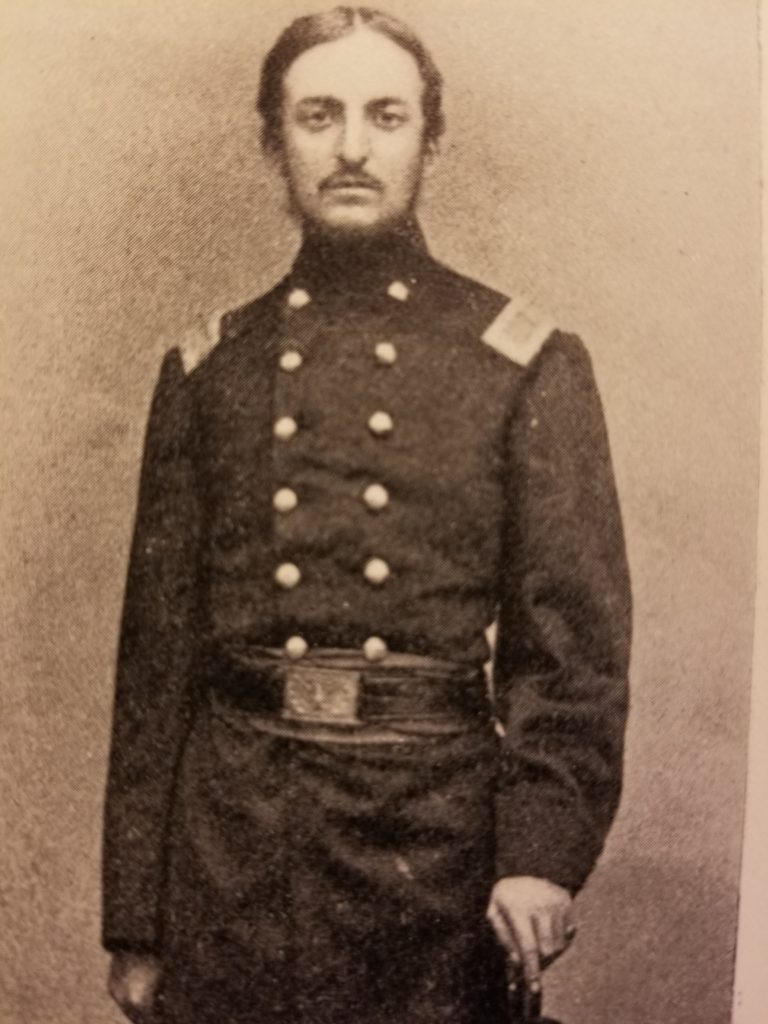

Thomas Fry Tobey. A Quaker, he forsaked his religion to volunteer to save the Union. Promoted to major for his actions at Fredericksburg, Major Tobey became severely ill during the Mississippi Campaign and resigned his commission. He later had a thirty year career on the Western frontier in the U.S. Army (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

On May 26, 1862, Tobey volunteered, against his parent’s wishes, to serve three months as a member of the Tenth Rhode Island Volunteers; he served as a sergeant in Company D. Hastily raised within forty-eight hours and rushed to Washington. Tobey’s brother John served as adjutant of the regiment. The Tenth, as well as its sister regiment the Ninth spent their term of service garrisoning the city before being mustered out on August 30, 1862. Tobey remained with the Tenth when he reported back to Rhode Island, where he assisted in raising a company for the Seventh Rhode Island. Tobey became a captain in the Seventh and was placed in command of Company E, a group of men raised in the Blackstone Valley towns of Cumberland, Woonsocket, and Smithfield. He defended his decision to his parents to take a commission in the Seventh, “I hope you will both do me the justice to believe that I have not chosen lightly in this important matter, and that it is not a boyish impulse, but a sense of duty to my country, that sends me into certain discomfort and danger, and possible death.”[3]

Tobey received his commission on September 4, and left Rhode Island with the regiment a week later. The officers of the Seventh had drawn lots to determine their seniority, with Tobey and Company E becoming the sixth ranked captain, as well as the sixth company in line. After performing garrison duty around Washington, D.C. and joining the Army of the Potomac’s Ninth Corps in October 1862, the Seventh set out for Fredericksburg, Virginia, arriving at the city’s outskirts in late November.[4]

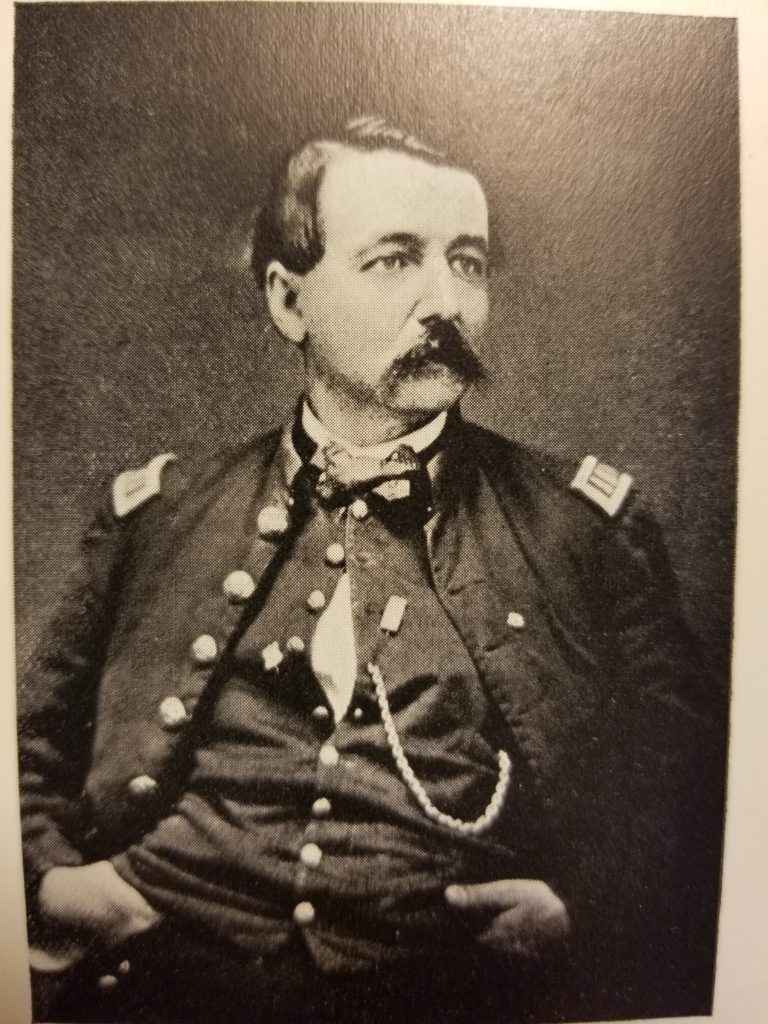

George A. Wilbur. Receiving his commission in the Seventh Rhode Island on the same day that he passed the Rhode Island Bar Exam, Wilbur was severely wounded at Fredericksburg. He ended the war as captain of Company K. After the war, Wilbur became a successful lawyer in Woonsocket and served as an associate justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

In volunteering for service in the Seventh Rhode Island, Tobey was excommunicated from the Society of Friends (Quakers); in Providence, a committee put before the entire membership that “his present position is incompatible with membership in our religious society.” Because he had broken the Quaker vows to remain peaceful and not take up arms, the Society voted to “disown thee as a member of our religious society.” Tobey would find religion again late in life.[5]

At 12:20 p.m. on December 13, 1862, the Seventh Rhode Island was ordered to the front as part of the assault at Marye’s Heights outside the Fredericksburg. Of 570 officers and men who took part in the battle, forty-nine were killed or mortally wounded, 145 were wounded, and three were captured. Tobey’s Company E suffered five dead and seventeen wounded.[6]

A week after the battle, Tobey wrote back to his brother John in Providence and told him about his experiences in the battle. This letter provides the most vivid, detailed account of the Seventh’s role at Fredericksburg. Unlike most Union soldiers, Tobey did not shirk in describing the fear and other feelings he felt during the battle, as well as the horrors he witnessed that day. He paints a moving, touching image of the terrible carnage suffered by the Seventh Rhode Island at Fredericksburg. This letter has been transcribed from the original at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library with footnotes added to identify the men Tobey described.

Camp near Fredericksburg Va., Dec. 20th 1862

My Dear John,

I have been too busy since the action to find time for more than a few hurried notes. To day, however, there seems a little more chance to write, and I will improve it by trying to give you some slight account of my share in the events of the last weeks.

To begin at the beginning. Last Wednesday night of last week we were ordered to have 3 days cooked ration ready and served out, with 60 rounds of ammunition. Thursday morning about 2 o’clock, I was awakened by the sound of the guns. Such a cannonade I never found any conception of. The rapidity of the discharges was more like musketry than like artillery fire. (This firing continued till evening with scarcely any cessation). Towards 8 o’clock we were formed into line and sent out to front- as that was next morning and advanced up on the hill just out of range of the rebel guns where we remained all day, expecting every moment to be ordered to charge across the bridge as some as it should be them across. At night we were ordered back to quarters. Leaving, as you hear, [sic] the bridge across and over troops in the town. (By the way, while we were waiting that day, I saw the first sight I ever saw in the military line- a brigade of cavalry advancing in line. It was a noble site + their horses kept their alignment better than any infantry of the same length of front that I have ever seen).

Before daylight next morning (Friday- we formed in line again- had whiskey served out to the men- and marched over the hill and down through a ravine to the pontoon bridge. The firing had ceased, except an occasional gun. Just as we got across the bridge, the rebs sent half a dozen shells from the batteries beyond the town, which passed over our heads, all but one or tell which fell in the water close to us. They had a beautifully accurate range. However we got safely across.

Well, I have partially fixed my assets. But I would give an order on the Paymaster for $20.00 (or twenty five cents in cash) for an hour’s talk with you. I could tell you a great many things that I don’t dare write, which might open your eyes, as mine have been opened. I dare say you think I am mistaken, but oblige me by keeping this letter till the war is over (a day I don’t expect to see, but which I hope you will). The mouths of the army will be unsealed then. But we must pass through great suffering first. Woe to the nations that is cursed with corruption in high places.

Well enough of this. To return to Fredericksburg. In the afternoon as we were sitting, smoking, and waiting the troops coming over the hill cross over us. One brigade band marched over in great style, playing Yankee Doodle. It sounded fine, and so did the rebel shell that came over our heads in about two minutes and struck right into the column, skedaddaling the band, and killing one of the soldiers. I never head music quit so quick.[7] Then for a few minutes the shells did come over us lively, hitting none on our side the river however. In a little while our heavy batteries on the other side silence the rebel batteries, and we had no more trouble that day. Towards evening we marched down in to the centre of the town and quartered ourselves for the night.

Saturday morning, after a short season of pillaging, our brigade was found and marched towards the outskirts of the town (still near the river bank) where we halted and waited for orders. Here Gen. Meagher’s brigade came along and halted beside us, and the General made them a short speech.[8] It was a very interesting speech, and the more interesting to us from the fact that our division was to follow theirs. Meagher is a fine looking fellow, and a great dandy- dresses entirely in black, with a silver star on each shoulder (no shoulder straps) and looks altogether like a black Brunswicker. By the way, the artillery and musketry began to sound heavy towards the front, and the shot and shell were constantly flying over us. Off went the Irish Brigade and very soon the firing grew still heavier, and the shot and shell began to drop even into our sheltered position. Lieut. Kenyon[9] was wounded here and one private killed + two or three wounded.[10] It was pretty tiresome to sit doing nothing + have the men hit. But before long up came the order to move.

So we fell into line, face by the right flank, and started up a side street towards the front (Each regiment of our brigade moved up a separate street). The shell whistled smartly over our heads, but no one was struck at first. Thank God the distance was not long, for the shot enfiladed at first. We had gone a little way, when a shell burst a few yards in front of me, covering me and my 1st sergeant with mud, [11] and filling my eyes with mud and gravel. A few fragments of stone or a piece of the shell (I don’t know which, but I fancy the former) also scratched my left hand. When the dirt flew in my eyes, I instinctively raised my hand to my face, and staggered, but someone called out “the Captain’s hit,” and that set me on my legs again. I said, “No, I’m not hurt,” and started ahead, rubbing my eyes.

In two or three second (for these things which I see happened in almost no time), and just as I was showing my hand to Lieut. Wilbur,[12] and saying “First blood for Co. E Wilby,” a big rifled projectile came walking down the street, taking steps of 20 yards or thereabouts. For a thing that came too fast to be dodged, it did not take a while to get past from the moment it first have in sight. I could think of nothing but a shark. It first struck a fence in the left near Col. Bliss, [13] went by him and over the regiment to the other side of the street, struck a building on that side, turned and next past the left of my company within about a foot of Lieut. Daniels, [14] passing between him and my 3d sergeant, and hurt no one in our Regiment after all.

Well we couldn’t stop to look after it, we were too near the enemy so in a moment more we filed to the right and crossed a railway cut (where our men began to fall), on to the field where we lay down behind a little ridge, having got there before the rest of the brigade. Indeed Ferrero[15] whom we were to follow, brought his brigade past us while we were laying there. You should have seen him take them in. He is brave, if ever a man was. So instead of having to follow the 2d Maryland (which didn’t get on the field at all) + the 6th NH + 48th Pennsylvania, as the Herald correspondent says, our regiment was under fire more than half an hour before one of them came up.

Well, we lay there, waiting to be ordered up to help Ferrero and now I had plenty of time to think. Now I am going to tell you how I felt and what I did for I know you will want to know, and as I believe I did my duty I shall say so. You will know what I mean, but don’t say anything about it to anyone not of the family, for a stranger would think it foolish and vain talk, but you know I don’t mean it for that.

I think the first thing that surprised me was that there was not more noise. To be sure there was a heavy fire of artillery and musketry over the ridge in front and solid shot, grape, rifle balls, + all sorts of projectiles were flying over us, and shrapnel and case shot bursting about our heads, but my notions were formed from Thursday’s cannonade, and I had expected a defining roar. (I heard noise enough later in the day) My next surprise was that I didn’t feel afraid. I was anxious, especially for my men of whom some had fallen so far, and rather expected to be hit every moment, but I felt no fear. Before we were ordered up, while waiting in the street, Kenyon was hit. I felt very nervous and uneasy, and had feared the feeling would grow on me when I got to the field.

Coming up the street I had been too busy keeping my files closed to think of anything else, except once, when the thought flashed through my mind whether the first man I saw shot would sicken me (which it didn’t), but now that I had nothing to do but to keep my men still, I was I confess agreeably surprised to find that if not indifferent to the danger, I at least did not fear it excessively.

Here Wilbur was hit. I was lying a few feet front of the company, he was in his place as a file closer, lying nearly behind me. A shrapnel shell, or a case shot, I don’t know enough about artillery to tell which, burst over our heads and threw bullets +c all round us. I turned round + asked if any one was hurt- no one answered and I was about to say something when Wilbur cut me short by saying, “My God Captain, I’m wounded.” I detailed 4 men and had him carried off the field. I confess, as I saw him carried off, I thought, ‘well I suppose my time will come next,’ but I cheered myself up with the thought that I was doing my duty.

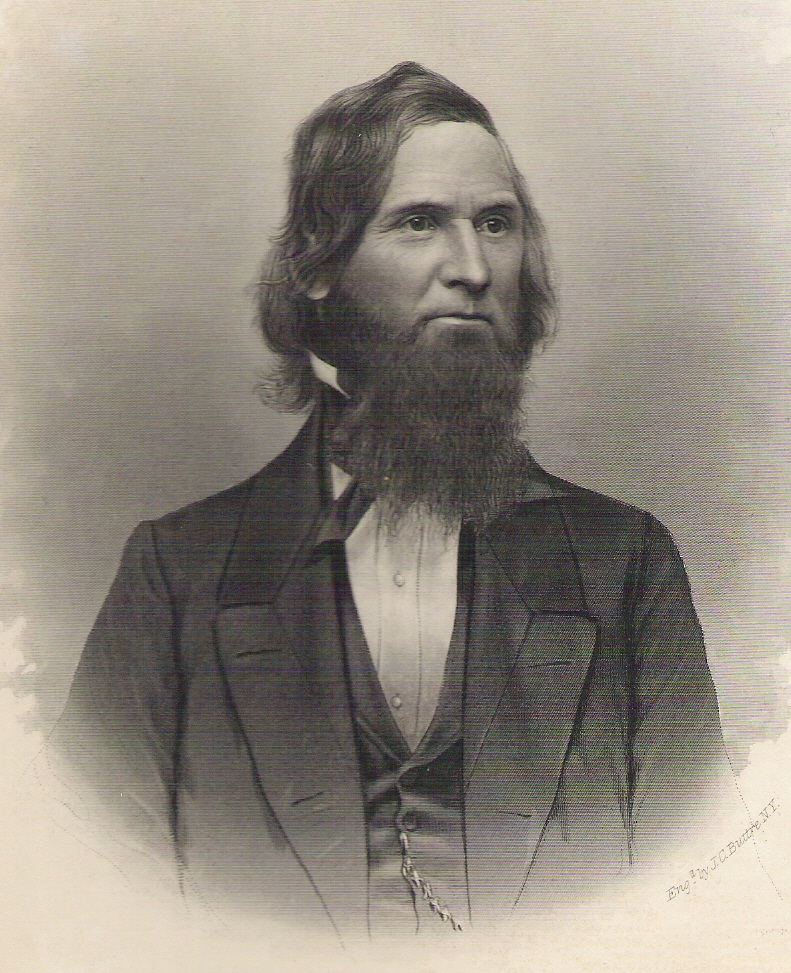

It was in this field that Lieut. Col. Sayles was killed.[16] Thank God I did not see him fall. Col. Bliss had a very narrow escape from being killed by the same shell. He was talking to the Lieut. Col. only a few moments before. They had a battery on our right that enfiladed us, and our loss would have been terrible had we lain there much longer.

Well after about half an hour or more of time, as I said, I heard the Colonel’s voice, as cool as if at battalion drill call out, “Battalion.” Up jumped every man in a moment, not a man flinched. “Forward, guide centre, march,” and off we went to the front, guiding on an old calico rag, that we have carried for 3 months.[17] Over a fence into the next field and then came the order, “by the right flank march.” The men were dropping pretty fast, but the regiment faced by the flank + marched off with perfect steadiness. Talk about it being impossible to drill under fire, but our regiment did it at Fredericksburg.

We moved by the flank until we got, I should think, nearly opposite to the battery that had worried us, and then marched by the left flank straight up towards the enemy (all this was done at the double quick, and better executed that I ever saw the regiment execute any maneuver of equal difficulty at battalion drill). Right in front of us was a rail fence, about 3 rails high, over which we had to climb, and here we lost many good men (I believe Manchester was hit here),[18] but we got well over this and formed line on the other side.

When we got on the other side however, I found that my company, being on the extreme left was separated by a board fence from the rest of the regiment. Supposing however that the regiment would advance straight forward, I started off with my company, along the line of this fence (at right angles to the one we had just climbed + on in line of battle), through an orchard, past a swail, and up to the crest of the hill in front of the batteries. Here I found 3 companies of the 12th (the only companies from that regiment that were in the action) who had just got up.[19]

I halted, called to my men to hurry up + being lighter than the average I had them dressed than, and gave the order “commence firing.” There for the first time I felt I and my company could go through any fire or do anything that men can do and more to. I felt big, no phrase will express it. I stood there and wave my sword and talked to my men as uncowardly as if I were a thousand miles from danger.

In the meanwhile I tried to see if I could see our Regiment beyond the fence to our right. Not being able to, I called for a man who would go to death with a message for Col. Bliss. Half a dozen of my men sprang forward in a moment. I picked out a smart active boy and told him to get to the other side of the fence and find where the Regiment was, and then to report to me. “I’ll do it Captain, and come back if I live,” said he, and off he went. In a few minutes he came back safe (and came out of the fight safe, I am glad to say) and repeated that after we crossed the fence, the regiment had aligned to the right and was now on the same alignment with us, but some little distance to the right.

So I called my company into line, faced them by the right flank, and off we started. Into the next field, and there were the colors on the ridge. “Company by the left flank march- now follow me boys,” said I, as loud as I could yell, and we charged up through the field. I tell you that was rough. As I started to lead the Company up, I could hear the rifle balls and the grape whistling by my head, and could see them cutting up the dirt on all sides, and at my very feet. I fancied I felt the wind of one ball at my cheek. The thought came into my mind, ‘This is death. A man might as well hope to go through a hailstorm untouched as to get to that ridge unhurt.’ But I knew my place was ahead of my men, and I kept there, though it cost me an effort, for a moment. I was badly scared but I kept on waving my sword, and calling to my men to keep up and though they fell all around me, I reached the ridge safely.

As soon as I got on the ridge, to the left of Co. A, I looked round, my company was close behind me, coming up in good shape, but now reduced. I noticed in an instant that a number of the men were done. In coming up I had only seen one fall (and felt another, who fell against me as he went down) but now I could recognize the figures of some of my men and I knew more must be down that I didn’t know of. But I had no time to feel heart sick- that came next day. I held up my sword for to mark the rallying point for the company (the only use I know of for an officer’s sword), got them together, and ordered them to lie down. Then after resting there for a moment I have them to order to commence firing again. We were I should think in very much such a position as Burnside’s brigade at Bull Run.[20] We lay under the crest of a little ridge where we could rise up to fire, and lie down to load. The ridge was not protection enough to keep men from being hit while lying down, but it was better than none. In every place it dipped men were there. The 12th Regt was quite well sheltered.

Before us was a valley, at the bottom of which was a canal, lay the rebel infantry line, and back of them, on the top of a steep hill, were their batteries. The position was too strong for us. As the Colonel says, “They might have defended such a position by rolling stones down in us.”

Well we lay there and fired away all our ammunition. It sickens me now to think of the waste of the energies and lives. The men behaved splendidly, but what use was it? Every now + then one of my men would turn to me and say “I’m hit Captain,” and drop. I heard no cries of pain, nor words of complaint. The men did nobly. I did little the rest of the day, but sit there, talk to the men to encourage them, do what I could for the wounded, and now + then, when I thought the men slackened their fire a little, go forward, and call on them to come up and fire. In fact that was all there was to be done. So I had plenty of time to look about. I was surprised (in fact the battle spent a great many of my previous ideas) to see how little confusion there was, and how easily I noticed everything going on anywhere near me.

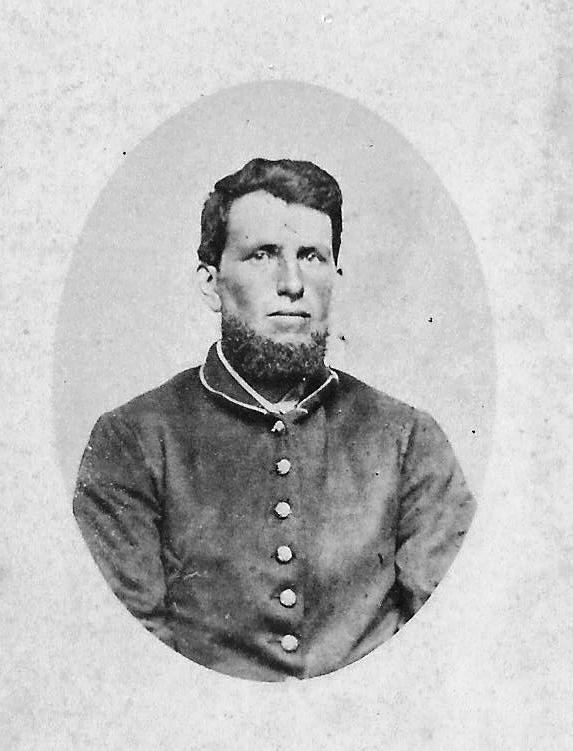

The first man I saw was the Colonel. I don’t know what to say about him. I can’t say anything half good enough. He came out large that day. He took the regiment in nobly and showed courage which I don’t believe can well be beaten. The second bravest men I saw that day were Col. Barnes[21] (commanding a brigade in Griffin’s division, I believe)[22] who rode by us several times at a slow trot- he was the only mounted officer I saw. Col. Potter of the 51st NY[23] and a sergeant of the 51st. But I saw very few men who were not brave. How could our regiment at any rate fail to do its duty with such a Colonel to set an example? Major Babbitt, too behaved finely.[24] The Colonel told me he was satisfied with my conduct, so I suppose I have the right to say that no officer of our regiment, so far as I know, or have heard, misbehaved that day. But the Colonel was the man that day. Our regiment swears by him ever since that fight.

Soon after we got on the field the 6th NH of our brigade- a splendid regiment- came up in line on our right. It was a fine sight. They marched up in quick time, closing the gaps as men fell, and keeping the alignment unbroken. The 51st NY (Ferrero’s old regt) did the same thing when they came up.

Well, I am spinning this out to a tremendous length, and shall never had it done if I go on at this rate. I will close up. During the long hours that we lay there, there was plenty of incidents which I could tell you, but which I will leave until if it please God, I get a chance to tell them to you with my own lips. This letter is entirely egotistical, as I warned you. I make it so because I don’t know about what was done outside of Sturgis’ Division.[25]

I was cooler and less excited on the field than I had expected. Indeed, I think it must be impossible in battle to realize the full extent of the danger. I have received a good many compliments since the fight for coolness and courage, which I cannot feel that I deserve. I had my duty to do, and tried my best to do it. If I had failed, I should have deserved blame, but I don’t feel that I have earned any praise. Two or three times it was not courage, but only a sense of duty that made me express myself.

But you should have seen the Colonel. Three times or more he took a musket, went up on the crest and fired. One of the times a man who was standing next to him was shot down. You can judge how we cheered for him—so conspicuous a mark as he is, too, and close to the colors, which had 16 holes and one shell hole through them. You can judge how ancious we felt for him, the fact that several of us formed and waved our swords to distract the enemy’s attention, and I for one, forgot any danger in anxiety for him. “I know it isn’t my business,” said he, “but I want the men to see I am not afraid.” And he is so kind hearted too.

After dark, when our supports had come up, and our cartridges were all gone, and we were still lying in our places, waiting for orders relieving us to come, the enemy’s fire slacked a little. I went up to the Colonel who was lying not very far from me, and we had a pleasant talk together. Just in the middle of it- crash!- came a smashing volley from the rebels and their batteries opened again. Talk of hot fire. I never imagined anything like that. Our Regt could do nothing but lie still, but the 51st NY and the other fresh regt which had just relieved us stood up to them splendidly. “Lie down Tom,” said the Colonel and down I dropped beside him. We lay there a few minutes, and then the Colonel said, “That battery on our right ought to open on them. Tom, do you think you can get to it?”

I tell you that it was rough. I don’t believe any man could have passed alive through that fire down to our right. But of course my duty was clear, so I said) as men do in books, you know) “I don’t know Colonel, but I can try.” “No,” said the Colonel after waiting a moment. “I won’t order you to any such service as that.” Of course I said that I needed no order to go in any duty that he thought was necessary. “Well, wait a little,” said he, and in a moment more, whoo-oo-oo-oo came a shell from one battery over us towards the rebs. “Bully for you,” said the Colonel. “That is one of our whistlers. Lie quiet Tom.” I can tell you it was a great weight off my chest.

I was just tightening my belt to run that terrible gauntlet, expecting nothing short of certain death, when that shell came. But it was as kind of the Colonel to keep me there till the last moment, as he did. He is bully. It is too bad that he will be lost to us soon- for if there is any decency left in Washington they can’t fail to give him his brigade. Well Church [26] will make a good Colonel if Sprague[27] will promote him, but no one can ever replace our Colonel. But we haven’t lost him yet.[28]

One more remark, and I have done. Grape is disgusting, shot, shell, canister, shrapnel for me. It sounds more like a flock of quails than anything else I can compare it to, and it makes such nasty sounds. But the sound is what I especially object to. That fluttering noise made me feel uncomfortable than all the other noises of projectiles put together.

Well, I will stop here. I hate to speak of the retreat from the field. Long after dark, when the wounded men had begun to mourn, and almost every step was over the body of a man, and then came the manly task of visiting the hospitals to find my men where I saw sights that made me wish myself back facing the rebel batteries. Finally, thank God on Monday evening came as safe retreat from that hapless enterprise. There came the reaction. All last week I couldn’t hear a sudden noise of any kind without standing. I couldn’t hear a gun in the distance without listening for a shell to whiz over my head.

There, I have done. I wanted to give you some little idea of how it felt on the field, because I thought you would like to know. I don’t pretend to give you any account of the fight or even of our share in it, but only to tell you of a few little things that might interest you.

Our regiment receives praises from all quarters. The 12th I am sorry to say skeddaddled- all but the 3 right companies. The fault is said to be in their officers. Major Dyer was wounded[29] before reaching the field by a piece of shell which hit him in the leg, but made no bruise or abrasion of the skin, or other external mark. However, he was unable to get to the field. You will be glad to learn that he is well now. Bah! God keep me from ever deserting my post. What a contemptable animal and coward he is!

Well good bye. Love to all at home. I have some bully old letter from the family and my various friends. Write to me when you can. Please send me the Atlantic for December + January- if not too much trouble. Love to Addie- Regards to Parsons + all my friends. Don’t show this letter to any one out of the family.

Well, God bless you

Yours

Tom

Merry Christmas

Immediately after the Battle of Fredericksburg, Colonel Bliss was faced with a crisis in command. The Seventh’s two other field officers, Lieutenant Colonel Welcome Ballou Sayles and Major Jacob Babbitt had both died at Fredericksburg. Furthermore, Second Lieutenant Charles H. Kellen was also killed, and eight other officers wounded. In the aftermath of the battle, half of the Seventh’s officer corps resigned and went home. Bliss promoted men who had distinguished themselves at Fredericksburg to the lieutenant positions in the Seventh, while moving up several promising lieutenants to captain and company command. As his new lieutenant colonel, Bliss appointed Captain George E. Church. As major, Bliss appointed Thomas F. Tobey who had proved his leadership capabilities at Fredericksburg. In a letter to Governor William Sprague, Bliss wrote of his new major, young and of not much experience, a brave soldier.” Tobey quickly purchased the new uniform of his rank and sewed on the gold oak leaves of a major.[30]

Colonel Zenas Randall Bliss. A native of Johnston, Bliss was an 1854 graduate of West Point. He molded the Seventh Rhode Island into a fine combat regiment. At Fredericksburg he earned the Medal of Honor for his heroism in the fight. After the Civil War, Bliss became an advocate for the Buffalo Soldiers and spent the rest of his career commanding them. Bliss served forty-five years in the Army and retired a major general. He died in 1900 and is buried at Arlington (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Major Jacob Babbitt, a wealthy banker and merchant from Bristol well respected by the men under his command, was mortally wounded at Fredericksburg (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

In the spring of 1863, Tobey and the Seventh were sent to Kentucky, and in June embarked for Vicksburg. Like dozens of men from the Seventh Rhode Island, Tobey’s health was “severely shattered by remittent fever.” Major Thomas F. Tobey was discharged for disability contracted in the service on February 9, 1864 at Point Burnside, Kentucky. He returned to Providence, but surprisingly, he enlisted in the United States Army on February 27, 1865. Enlisting as a sergeant in Company F, Second Battalion, Fourteenth Infantry, and by May 1865 he was a first lieutenant.

First Sergeant Charles H. Kellen of Providence served in Company F. Mortally wounded at Fredericksburg, he was posthumously promoted to second lieutenant for heroism on the field ((Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Tobey remained in the army, but promotion in the Regulars to higher rank was always extremely slow, so it was not until 1874 he became a captain. He was active in the Indian Wars of the 1870s and 1880s, seeing combat in Oregon, Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Tobey married Marie Wingard in 1881 and had two children, who both died young. He was active in the Masons, Grand Army of the Republic, as well as the Military Order of the Loyal Legion. Despite his many years of service in the Fourteenth Infantry, Tobey always retained a deep interest in the Seventh Rhode Island. When he found out that the veterans of the regiment had published a history of the Seventh in 1903, Tobey wrote to author William Palmer Hopkins two years later, “I really must have the history of the dear old regiment. It was only the other day that I learned that the book had been published. I wonder why I was not notified.” After receiving his copy of the book two weeks later, the old soldier wrote back to Hopkins, “I have read it with deepest interest, and how it brought back to me the days of our campaigning together. You have done a most valuable work, which every man of the old Seventh will cherish.”

Lieutenant Colonel Welcome B. Sayles of Providence was a prominent Democratic politician who ran the Providence Press, the organ of the Rhode Island Democratic Party. He had been a strong supporter of Thomas Wilson Dorr in 1842. At Fredericksburg, he was killed early in the fight as he was hit directly by a shell that evacerated him.

Tobey retired from the United States Army as a captain in 1892, but was placed on the retired list as a major in 1904, allowing him to earn a larger pension. Major Thomas Fry Tobey converted to Catholicism late in life. He died on June 7, 1920 at Sea Isle, New Jersey and is interred at North Burial Ground in Providence.[31]

Alfred Sheldon Knight served in Company C of the Seventh. A dairy farmer from Scituate, he survived the assault on Marye’s Heights, but died of pneumonia six weeks later.

[Banner Image: The Seventh Regiment of Rhode Island in action at Fredericksburg, by Alan Archambault (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

NOTES

[1] “Introduction to the Thomas Fry Tobey Papers,” http://drs.library.yale.edu/fedora/get/beinecke:tobey/PDF, accessed January 27, 2017. [2] William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War: 1862-1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1903), 326-327. Thomas F. Tobey to John Hay, April 8, 1862 and June 28, 1864, Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, RI. [3] Descriptive Book of Company E, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Rhode Island State Archives, Providence, RI. Thomas F. Tobey to Parents, July 11, 1862, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT. [4] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 1-22. Zenas R. Bliss, The Reminiscences of Major General Zenas R. Bliss, 1854-1876: From the Texas Frontier to the Civil War and Back Again, Edited by Thomas T. Smith, Jerry Thompson, Robert Wooster, and Ben E. Pingenot (Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2007), 312-315. [5] Samuel Austin to Thomas F. Tobey, December 20, 1862, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. [6] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 57-59. Company E Seventh Rhode Island , NY Descriptive Book. Providence Journal, December 19-30, 1862. [7] This was the band of the Twelfth New Hampshire Volunteers. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 40. [8] Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher, 1823-1867, was the leader of the Irish Brigade, composed of the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York, as well as the 28th Massachusetts, and the 116th Pennsylvania. He was an Irish revolutionary, who fled to America, becoming a leader in the New York Irish community. See Timothy Eagan, The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 2016). [9] David R. Kenyon, 1833-1897, was originally the first lieutenant of Company A. A native of Richmond, RI he was a mill superintendent before the war. Wounded at Fredericksburg, he was promoted to captain of Company I, but resigned on March 2, 1863. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 345-346. [10] The first man killed in the Seventh Rhode Island was Private Nicholas W. Matthewson, a farmer was West Greenwich who served in Company F. The same shell wounded Nicholas’s brother Calvin, as well as James W. Bates, also of Company F. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 43. [11] The first sergeant of Company E was Charles L. Porter, a twenty-one-year-old shoemaker from Burrillville. Porter was wounded at Bethesda Church on June 3, 1864 and survived to be mustered out on June 9, 1865. He later moved to Thompson, Connecticut and died there in 1900. Company E Descriptive Book. [12] George A. Wilbur, 1830-1906, of Woonsocket was the second lieutenant of Company E. Wilbur had a harrowing Civil War career. He was shot in the thigh at Fredericksburg, and nearly died of disease contracted in Mississippi in 1863. He ended the war as captain of Company K. A lawyer before the war, he later became an associate justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court and was highly active in veterans affairs. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 357-358. [13] Colonel Zenas Randall Bliss, 1835-1900, of Johnston was the commander of the Seventh Rhode Island. An 1854 West Point graduate he had served on the Texas frontier before returning to Rhode Island in 1862 to command the Tenth and later the Seventh Rhode Island Regiments. A born leader, Bliss was universally beloved by his men. He earned the Medal of Honor leading the regiment at Fredericksburg. Mustered out of volunteer service in 1865, he spent much of the next three decades in Texas commanding the Buffalo Soldiers. Bliss is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 311-314. [14] Percy Daniels, 1840-1916, served as the first lieutenant of Company E during the battle. A native of Woonsocket, he was an engineer before the war. Daniels was promoted to captain after the battle and later to lieutenant colonel. He commanded the regiment from May 1864 through the rest of the war, but was not respected by the men. He later moved to Kansas and became involved in politics. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 322-325. Stephen Farnum Peckham, “Recollections of a Hospital Steward in the Civil War,” Newport Historical Society, Newport, RI. [15] Brigadier General Edward Ferrero, 1831-1899, commanded the Second Brigade, Second Division, Ninth Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg. He was relieved of command in 1864 for his failure at the Battle of the Crater. New York Times, December 13, 1899. [16] Lieutenant Colonel Welcome Ballou Sayles, 1812-1862, was the second in command of the Seventh Rhode Island. A prominent member of the Providence Democratic Party, Ballou had been an active participant in the Dorr Rebellion, and published the Providence Press before joining the Seventh Rhode Island. At Fredericksburg he was hit in the chest by a Parrott shell fired from Marye’s Heights and was eviscerated, pieces of his body flying over members of the regiment, including Colonel Bliss who was covered head to toe in Sayles viscera. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 314-315. [17] The Seventh Rhode Island had not been given a flag when they left Rhode Island in September 1862. To make up for this, the members of Company D, the Color Company of the regiment, purchased a small American flag in Baltimore when the regiment passed through the city. It was nailed to a rake handle and carried into battle at Fredericksburg by Sergeant Frederic Weigand. It was nearly ripped in half by a shell and hit by sixteen bullets. Weigand received a battlefield commission for his heroism at Fredericksburg. The flag was known as the “Fredericksburg Flag.” A larger, proper National color was received in January 1863 from the “Ladies of Providence.” Today both flags are at the Rhode Island State House. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 291-293. [18] Sergeant Major Joseph Swift Manchester, 1841-1872, of Bristol lost his left arm at Fredericksburg. He later became a captain in the commissary department. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 363. [19] Although the Twelfth Rhode Island lost twenty men killed and over eighty wounded at Fredericksburg, the regiment disintegrated under fire, men fled for their lives under fire. A nine-month regiment, the Twelfth was led by Colonel George Browne, a former Congressman. Poorly equipped, and poorly led, the Twelfth’s flight was recorded by many Rhode Island soldiers. Pardon E. Tillinghast, History of the Twelfth Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War 1862-1863 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1904), 37-45. [20] At Bull Run, on July 21, 1861, Ambrose Burnside had led a brigade consisting of the Second New Hampshire, Seventy-First New York, as well as the First and Second Rhode Island Regiments. The Second Rhode Island fought alone for nearly an hour before reinforcements finally came up. Brent Nosworthy, Roll Call to Destiny: The Soldier’s Eye View of Civil War Battles (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 33-83. [21] Colonel James Barnes, 1801-1869, led the 18th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War. A West Pointer, he later became a brigadier general and was wounded at Gettysburg. Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), 20-21. [22] Charles Griffin, 1825-1867, was a West Pointer and career army officer who spent much of the war commanding a division in the Fifth Corps. Warner, Generals in Blue, 190-191. [23] Colonel Robert Brown Potter, 1829-1887, led the Fifty-First New York. He later commanded a brigade and division in the Ninth Corps as a brigadier general. After the war he settled in Newport, Rhode Island where he died. Warner, Generals in Blue, 382-383. [24] Major Jacob Babbitt, 1809-1862, had attended Norwich University, graduating in 1826. A wealthy Bristol banker, he was heavily involved in civil affairs in his native town, as well as active in the Rhode Island Militia. At Fredericksburg, he was shot in the chest as he attempted to order the 127th Pennsylvania Regiment to stop firing over the heads of the Seventh Rhode Island when they were pinned down in front of Marye’s Heights. He died ten days later on December 23, 1862 and was buried in Bristol in one of the largest funeral’s Rhode Island has ever seen. Julia Emily Babbitt, Sketch of Major Jacob Babbitt, 7th Rhode Island Regiment (Bristol, RI: NP, 1890), 1-10. [25] General Samuel D. Sturgis, 1822-1889, commanded the Second Division, Ninth Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg. He later became colonel of the Seventh Cavalry. His son was killed at the Little Big Horn. Warner, Generals in Blue, 486-487. [26] George E. Church, 1835-1910, served as captain of Company Cat Fredericksburg. An engineer, he had extensively traveled throughout South America before the Civil War. Given a battlefield commission as lieutenant colonel in the Seventh Rhode Island, Church became colonel of the Eleventh Rhode Island in March 1863, and was mustered out in July 1863. After the war he returned to South America. Today his large collection of South Americana is housed at Brown University. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 315-319. [27] William Sprague, 1830-1915, served as governor of Rhode Island from 1860-1863, before his election to the United States Senate. As captain-general of the Rhode Island Militia, Sprague had led the First Rhode Island Regiment to war in 1861 and had two horses shot out from under him at Bull Run. As governor of Rhode Island, Sprague approved of and signed the commissions of the officers in the Seventh. Henry Wharton Shoemaker, The Last of the War Governors: A Biographical Appreciation of Colonel William Sprague (Altoona, GA: Altoona Publishing Co., 1916). [28] Colonel Bliss was nominated for promotion to brigadier general for his gallantry at Fredericksburg, but was turned down for promotion. In addition to earning the Medal of Honor, he also earned a brevet of major in the Regular Army. Reminiscences, 333-334. [29] Major Cyrus Grinnell Dyer, 1831-1892, was a lawyer in Providence before the war. He had seen prior service in the First and Second Rhode Island Regiments before becoming major of the Twelfth Rhode Island in October 1862. Tillinghast, Twelfth Rhode Island, 336. [30] Regimental Descriptive Book, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Rhode Island State Archives. Zenas R. Bliss to William Sprague, December 30, 1862, Rhode Island State Archives. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 326-327. [31] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 327. Providence Journal, June 10, 1920. Thomas F. Tobey to William P. Hopkins, November 1, 1905 and November 20, 1905, author’s collection.