Eighteenth-century American society allowed women to take on some roles outside of homemaker. Women were plaintiffs in court cases, administrators of wills, held powers of attorney, and were property owners. We know from reading merchant account books, financial agreements. advertisements, wills, epitaphs, and diaries that there were women who ran businesses in colonial times. Many of these women were widows.[1]

Several enterprising females emerged as business managers in the mid-eighteenth-century urban seaport of Newport. Shopkeepers Alice Gould, Mary Maylem, Sarah Peckham, and Sarah Rumreil advertised in Newport newspapers their shops near the waterfront. They sold textiles, household tools, and produce. Sarah Arnold and Lydia Townsend made clothes-to-order for men and women. Sarah Leach and Mary Gould Almy each ran a boarding house. Mary Pinnegar was a tavern keeper, a popular occupation for widows; her tavern stood on Banister’s Wharf. Ann Franklin, after her husband James’ death, (he was the brother of Benjamin Franklin), printed Rhode Island government documents.[2]

Mary Cowley was one of these extraordinary Newport women. She was the proprietor of both the Cowley Dancing School and the Crown Coffee House on Church Street.

Most people grasp that running an inn could be useful to the community and profitable to the woman. However, the idea of a woman teaching dance to survive economically requires investigation. Why did the general populace, those who were wealthy and those who aspired to more status, desire this experience for themselves and their progeny? How did such schools affect political and economic life in Newport for residents and soldiers, under military occupation by the British, then during a French occupation, and in the recovery from war? This research looks at how Mary Cowley as a dance master became an authority of societal standards.

First, as an integral part of education, dance demonstrated to peers and adults that a young person knew how to show social grace and good manners. John Locke, Alexander Pope, and Henry Fielding commented that dance taught a person etiquette and deportment, which made a person accepted in various social, economic, and political situations.[3] Knowing how to dance gave young persons the ability to communicate family status in the clothes they wore, to exhibit the civility they had learned in the way to greet others with a bow or curtsy, and to express the manners they attained in learning how to drink and eat with ease while dressed in proper attire. Secondly, dancing provided opportunities to enjoy the company of the opposite sex in a welcoming and socially permitted setting. As such, all classes in society found ways to enjoy dancing to music.[4]

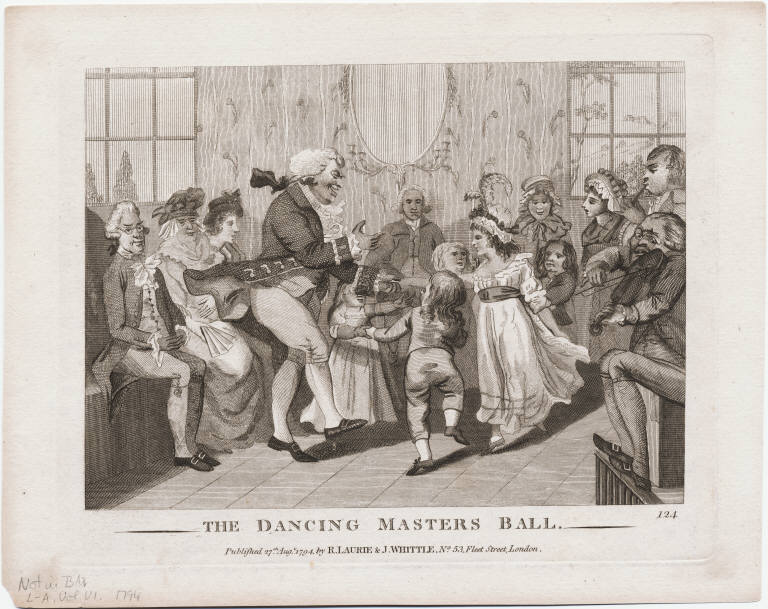

“A Country Dance,” printed in London by W. Pearson and John Young in 1728. The longwise rows for a country dance were the most typical dance of the time (Library of Congress)

Finally, dancing helped breathing, decreased stress, and improved overall well-being, as well as being fun. Dance was exercise, as it took physical skill to attain balance. Even ministers allowed their children to attend, if the assemblies did not distract from academic studies, occur late into the night, or require wasteful expense.[5] Dance helped with cultural, physical, and economic improvement.

A Dance Master taught young people how to step with the beat of the music, “Head upright…Eyes lively…Body with a swing in motion…Foot light and easy.”[6] An instructor could teach from published books, but personal practice and training in the skills were a prerequisite. The teacher had to have knowledge of the French names for many of the steps, such as chassé, contretemps, and pas de bourrée. Mary Cowley had to be familiar with “fashionable” musical pieces for the Minuet, Cotillion, or English Country Dance. The Master understood music, the meter, tempo, and beat of each composition. Although sheet music was readily available and inexpensive, a respected master decided which musical compositions should accompany her students based on their ability level.[7] Cowley’s job was like that of the Riding Master, Music Master, or Drawing Master, for which there were standards of excellence.[8] She held private lessons, public schooling, and pre-ball assembly practices. Certain qualities made her successful; she had to be generous and agreeable as well as strict.

To manage such a business, required Mary Cowley to market her skills through advertisements, which addressed the needs of her potential customers—those who had the financial ability to pay for her service.[9] She accepted some children, who were not blessed by “Birth, Fortune, or Education.” However, Mary Cowley insisted her protégés be willing to learn proper manners, show punctuality, and be of “good character.”[10] She set payment so that both craftsmen and merchants could afford lessons for their children allowing fluidity of class relations. Cowley emphasized she had “no respect for Persons who show Rudeness or Indecency.”[11] As long as students followed her rules, and paid her reasonable fees, position in society did not prevent inclusion.

For her business Mary Cowley had to cover the costs of hiring a local fiddler or fifer.[12] For a Ball, the price paid by the gentlemen covered the costs of printing the tickets and refreshments, usually cakes, nuts, and raisins. She had to know food and beverage caterers.

Although we do not know the exact method of financing, based upon what other men and women did during this era, Cowley used cash or may have exchanged her services for goods (such as clothing, food, and tools). Cowley had to know how to balance expenses and income and budget her finances over slow times for her business. The use of “book debt,” i.e., accounting debits and credits, and the use of promissory notes, i.e., payment returned over time, were also regular practices.[13]

Cowley advertised in the local newspaper from the 1760s through the 1780s, encouraging students to enroll at her school of dance. “Next Thursday evening I shall open school, and every Thursday after for the season, on condition the gentlemen and ladies conform to the rules, act in character, and behave with a decency agreeable to that most approved accomplishment.” She provided the rules of those dancing in her hall:

Every lady attends for the pleasure and improvement of dancingEvery lady will be punctual at sunset; no lady shall be admitted an hour afterNo lady shall engage, either in school or out, to dance with any gentleman without my approbationNo lady shall refuse being taken out by any gentleman that’s admitted by a ticket, without giving a sufficient reason, on pain of being publickly reprimanded, and immediately dismissedNo gentleman nor lady shall come in an undressNo gentleman shall be admitted without a ticket None to be admitted that don’t danceThe number of gentlemen not to exceed sixteenThe hours from five to nine

Mrs. Cowley encouraged student progress by offering to hold a ball in her assembly room beginning at 4 o’clock the following Monday. “Any parents that incline to see the performances of their children, who are presented with tickets, shall meet with a kind reception.” She choreographed solo performances of the hornpipe or jig as well as cotillions and country dance. The culmination activity “kept everyone on their toes,” from dance instructor to parents or grandparents who evaluated the results of her instruction. In addition, with refreshments being served, the students had to learn elements of socialization, including thinking of topics for conversation (including what is now known as small talk).[14]

As the leading teacher of dance in Newport from about 1760 to 1790, location was important. Mrs. Cowley’s home was in the heart of Newport close to the wharves, Colony House (later State House), town market, and mall (green space, i.e., the Common and Parade). On the south side of Church Street, Cowley’s home was the second lot and third house east of Thames Street near Trinity Church.[15] The size of a room limited the number of dancers and audience, but with chairs moved to the perimeter of the room and no additional furniture therein, one or more of her second-floor rooms could serve for an assembly. By 1769 a second-floor addition on the eastern side of her house provided a much needed, larger space about twenty feet by fifty feet. Cowley’s Assembly Hall during the Revolutionary War opened to British officers and then to the French, and to town celebrations such as the arrival of General Washington.[16]

Personal History

Mary Dunbar’s father, George Dunbar (ca 1697-1754), married Elizabeth Hicks (1701-ca 1741) at Trinity Church in Newport on June 15, 1718. Dunbar was of Scottish heritage, while his wife descended from families who were well-established Newport commercial or social leaders. Dunbar became a freeman (voter and taxpayer) of Newport and vestryman at Trinity Church, an Anglican institution.[17] He was both a successful merchant and a respected deputy judge on the Rhode Island Admiralty Court.[18] Born in 1726, Mary was the third child of four.[19] In 1735, when Mary was nine years old, Peter Pelham (1707-1751), who had taught dance for a decade in Boston, arrived in Newport and ran a successful school and dance assemblies for three years for children of her social class.[20] This was a decade in which there was a constant stream of vacationers to Newport from the South, visitors who enjoyed dance as a form of social interaction. It was a time for “turtle frolics,” which were festive dance parties on Goat Island run by a group of young bachelors of Newport.[21]

Since Mary married at age seventeen to mariner William Sweet in 1742 and had three children by 1755, a career as a businesswoman may not have crossed her mind.[22] However, her wealthy merchant father passed away in 1754, as did her husband in 1756, having served on privateer ships during colonial wars.[23] While there is no indication of cash inheritance, Mary along with her older sister, inherited the Dunbar home on Church Street.[24] Mary Sweet lived there with her children, including a newborn daughter.

Four years later, on January 8, 1758, having struggled as a young widow with three children, Mary Sweet married a second time; she was thirty-two. Her husband was widower Joseph Cowley, a merchant who also attended Trinity Church, and inherited Cowley Wharf from his deceased wife, Penelope Pelham.[25] Together the couple had a daughter, Rosalia Cowley.[26] They became a blended family with seven children, three of whom were teenagers. That is the period when she started to teach dance, including a son of merchant John Banister, her brother-in-law by marriage to Cowley. In October 1759, Banister paid “Expences on my son Thomas to Mrs. Cowley, his Dancing Mistress…£20.”27]

When second husband Joseph Cowley died just four years later in 1762, there is no indication of a monetary inheritance. Penelope Cowley was twenty, Elizabeth twelve, Mary seven, and Rosalia just two. The will of second husband Captain Joseph Cowley revealed trading connections in the Caribbean, but not income for the family.[28]

A Cultural Entrepreneur

Over the next decades, Mary Cowley maintained her businesses on Church Street. From at least 1768, her house served as an inn. At her home, called the Crown Coffee House, Mary Cowley rented rooms to judges who were in town when the court was in session during March and September. Legislators from off-island arrived when the General Assembly met in Newport every May and some months of October in rotation with Providence, South Kingstown, Bristol, and East Greenwich.[29] Based on her probate inventory with dozens of plates and mugs, Mrs. Cowley served coffee and other beverages, and food, to her boarders for breakfast (9 a.m.), dinner (usually at 2 p.m.), or supper (7 p.m.) when not running her dance school. Places called coffee houses also often served alcohol, but there is no indication in the probate inventory of glassware for alcoholic beverages; nor do the town council records show a liquor license ever issued to Mrs. Cowley. With a total of twenty chairs, nine tables, and six beds, as well as a fireplace in each room, guests could find comfort at her inn.[30]

Mary Cowley taught dancing school in the fall and winter, with an occasional spring and summer school over the years. By contrast, the inn service ran year-round and occasionally was a location to sell books and textiles or as an auditorium for itinerant actors, singers, and traveling dentists! She had to work, but it is likely that her two older unmarried daughters living in her household assisted her in running the businesses.[31]

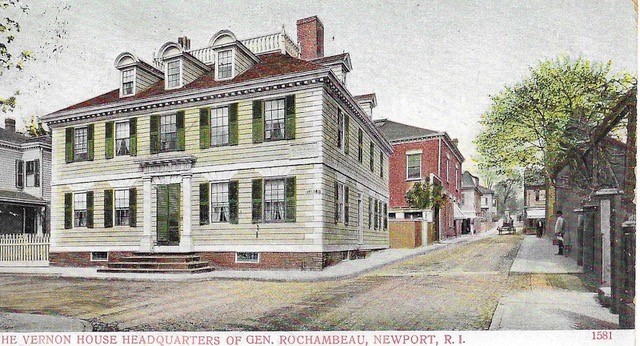

Postcard of the Vernon House, the headquarters of the Comte de Rochambeau and where he held a number of dances in 1780 and 1781 (Christian McBurney Collection)

From 1776 to 1781, during the American Revolution, dances provided year-round entertainment and recreation for officers of the British and then French armies. A dance was a venue for the occupying military leaders to meet local merchants for supplies and financiers for money. Sponsoring a Ball honored the arrival of a dignitary or celebrated a special event, such as a birthday of the king or a victory in battle. There was no end to the possibilities for public assemblies or afternoon dance parties.[32]

When the British army established a military base of over six thousand officers and soldiers in Newport in December 1776, it would be three years before they departed in October 1779 (although the number of soldiers fluctuated, sometimes falling to just over three thousand men). The British army included not only British officers and soldiers, but also German officers and soldiers (often called Hessians), and Loyalist officers and soldiers (sometimes called Tories).

Mrs. Cowley made the decision to hold a great ball in January 1777, the month after the British occupation began, at her Church Street location. She extended an invitation to Lord Hugh Percy, a prominent English aristocrat who took over command at Newport when General Henry Clinton left for London. She invited Elizabeth Pelham Harrison, widow of colonial architect Peter Harrison.[33]

During the three years of the British occupation of Newport Mrs. Cowley regularly hosted dancing assemblies and made a decent living. The Newport Gazette, the British-funded newspaper, published her personal thanks to the garrison and town.[34]

The British army evacuated Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island in October 1779, and a French expeditionary force occupied the same locations starting in July 1780. While the French occupied Newport, from July 1780 through June 1781, the operation of Mrs. Cowley’s dance school continued. The French commander, Comte de Rochambeau (1725-1807), recorded an event in his memorial book as taking place on March 7, 1781. On that day, General George Washington was in the city to meet with Rochambeau. “In the evening a ball was given at Mrs. Cowley’s Assembly Room, graced with the presence of the most fashionable families of the town and many gay French officers.” The big story from that evening was that General Washington danced for much of the night with daughters of town patriots. Peggy Champlin chose, “A Successful Campaign,” as the music for her dance with the General.[35]

Planning a final farewell to their Newport friends before heading for Boston to exit America, French officers stopped in Newport from November 9 to 16 in 1782. The Newport Mercury edition of November 16 included the following:

Prince de Broglio, son of the Mareschal de Broglio, the Comte de Segur, son of the Prime Minister of France, the Comte de Vauban organized an elegant Ball at the Assembly Room of Mary Cowley for the Ladies and Gentlemen of the Town. The Room was ornamented in a splendid Manner a Sight beyond Expectations with great Taste and Delicacy by Monseigneur Dezoteux, an aide to the Baron de Vioménil. [36]

After the Revolutionary War, up to 1788, there is a record of Mrs. Cowley continuing her dance school. By this juncture she was in her fifties.[37] Not only was she managing the dancing school but also her inn with a new name, the American Coffee House.

Advertisement for Mary Cowley’s dancing classes in the July 19, 1783 edition of the Newport Mercury. Mary was then almost 60 years old (Collection of the author).

Cowley had a core message used repeatedly over her thirty-year career to convey positive attitudes towards her teaching and a recognition of the comfortable space of her public accommodations. She offered “Gentlemen and Ladies to reserve rooms for informal gatherings on a weekly basis at one dollar per person with “Music, Lights, Cards, and Refreshments.” She also noted her gratitude for the public support of her business.[38]

In addition, Mary Cowley opened her home to theatrical performances. One week she invited members of the American Company of Comedians to perform songs and dialogues. Another time there were musical scenes from Henry Fielding’s “The Miser” and “The Virgin Unmasked.” There were also evenings with popular music, such as “Love in a Village,” a ballad opera in three acts by Thomas Arne. Another evening a performer sang all the parts of the cantata for “The Beggar’s Opera” by John Gay. Each entry fee was one quarter dollar, or two shillings per person. Itinerant singers, musicians, dancers, and actors gave Newport residents an opportunity to hear and see the contemporary presentations of Drury Lane and Covent Garden in London.[39]

Mary Cowley neared the end of her remarkable life. On the sixth of January 1791, Mary Cowley’s death notice appeared in the Newport Herald and her burial at Trinity Church was recorded in church records.[40] Newport County probate records showed that at her demise she held household goods with a total value of £33.14.6, certainly not the estate of a wealthy woman.

Mary Cowley’s legacy continued as one daughter, widow Mary Penrose, lived at the Cowley home on Church Street and taught reading, writing, arithmetic, Latin, and Greek to students for between twelve to eighteen shillings per quarter year. From 1794 to 1802, advertisements in the Newport Mercury show that Ms. Penrose continued her mother’s dancing school and managed the inn.[41]

In conclusion, Mary Cowley lived a remarkable life with a respected position in the Newport community. She was one of a unique group of women who married, had several children, and became widowed, yet managed to be productive and creative in running her businesses in colonial and Revolutionary America. Hard work, wise monitoring of her resources, and networks of exchange reveal that Cowley affected commerce, social change, and the political culture of the eighteenth-century seaport.[42] Mary’s story reveals a woman of risk taking and perseverance during changing conditions in the war interacting with foreign officers and in a bustling then devastated post-war Newport economy. Moreover, her life was freer than those of many women in that she was able to fulfill her goals without societal or legal interference.

Mary Cowley’s drive derived from a need to provide for her family. Running an inn for boarders as well as a dancing school was no easy task. She was a role model, showing acumen in developing her business. Sharing her knowledge about the value of dance as well as showing the connection between dance and social advancement met her goal as an instructor for young people in Newport. Six male instructors attempted unsuccessfully to wrest a share of the teaching of dance during Cowley’s tenure. Mary Cowley was unique, being one of only sixteen female dance masters noted in newspaper ads of her era anywhere in the country. [43] In addition, her interests were trans-Atlantic as seen in music she used at the school, as well as the contemporary books she sold, the performers she invited, and the varied activities she offered at her inn to expand the cultural horizons of Newport residents. While Mary Cowley’s vocation was essential to the economic survival of her family, her commercial ability was a gift to the cultural life of the Newport community and for thirty years filled a growing need in a civil society—even during times of war.

Notes

[1] Sara T. Damiano, To Her Credit: Women, Finance, and Law in Eighteenth Century New England Cities (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021); Kim Todt, “A Venture of Her Own: Early American Women in Business,” Early Modern Women, vol. 10, no. 1 (2015), 152–63, accessed at https://www.jstor.org/stable/26431364; Elizabeth Anthony Dexter, Colonial Women of Affairs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1924). [2] Marian Mathison Desrosiers, John Banister of Newport: The Life and Accounts of a Colonial Merchant (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2017),79-83; Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor, The Ties That Buy: Women and Commerce in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2009), 51-53, 85, and 89; Patricia Cleary, Elizabeth Murray: A Woman’s Pursuit of Independence in Eighteenth Century America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000); Christina J. Hodge, “The Genteel Revolution: Material Lives of Newport’s Middling Sorts,” Salve Regina University, PowerPoint Lecture, April 25, 2012. [3] Trevor Fawcett, “Dance and Teachers of Dance in Eighteenth Century Bath,” vol. 2 (1971), 27, accessed at https://historyofbath.org. [4] Kate Van Winkle Keller and Charles Cyril Hendrickson, “Dances of Washington’s Time” (2015), accessed at www.mountvernon.org/; George Washington, A Biography in Social Dance (Sandy Hook, CT: The Hendrickson Group, 1998), 18-23; Ralph G. Giordano. Social Dancing in America: A History and Reference (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2007); John Fitzhugh Millar, Country Dances of Colonial America (Williamsburg, VA: Thirteen Colonies Publishing, 1990). [5] Joy van Cleef and Kate van Winkle Keller, “Music in Colonial Massachusetts 1630-1820,” The Massachusetts Colonial Society, vol. 53: 4-10 (2007), accessed at https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/2007; Kate Van Winkle Keller, Dance and Its Music in America 1528-1789 (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2007), 300-314. Seventeenth century Puritans decried public dancing and the Maypole, but generations later debate changed views. [6] François Nivelon, The Rudiments of Genteel Behavior (1737) (reproduced at Paul Holberton, London, 2003). There is no known description of Mary Cowley to know if she was slim or stout or stood with a dancer’s posture. Given she was a dance instructor, she likely was a person of good health and stamina. [7] Van Cleef and Keller, “Music in Colonial Massachusetts, 12-14. London publishers offered a pocketbook format in the 1720s. The most popular dances on the Continent were in English language books, but the American Revolution interrupted the supply. [8] Fawcett, “Dance and Teachers of Dance in the Eighteenth Century,” 27. Music masters and foreign language masters were from families of professionals (physician, clergyman, or lawyer). Dancing teachers rarely came from an educated or wealthy background. [9] J.L. Bell, “Colonial Newspaper Advertising Rates,” Boston 1775 blog (June 5, 2017). In the 1770s, eight colonial newspapers charged between three and seven shillings for the first ad and one shilling for each additional week. The Providence Gazette charged four shillings for the first three weeks. One shilling was equal to twelve pence. [10] Newport Mercury, Dec. 19,1763. The Assembly was not a place for young Ladies to “pre-engage” with men; they were there to dance. [11] Newport Mercury, Oct. 17,1768; Fawcett, “Dance and Teachers,” 31 and 38. What began among English court nobility filtered down to the children of prosperous businessmen and tradesmen in public assembly halls and gardens at seaside resorts. Not until about 1800 in Newport were there several free people of African heritage who operated businesses and owned property in Newport. [12] Wilkins Updike, A History of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett, Rhode Island (New York: H.M. Onderdonk, 1847), 185. Van Winkle Keller, Dance and Its Music, 215. Updike commented that enslaved people were the musicians who played at balls, celebrations for the harvest, and Christmas. During the Revolution, a Newport resident of African heritage, namely Nkrumah Mireku (also known as Newport Gardner) played the violin and composed music. John F. Millar, “Newport Gardner: From Slave to Musical Composer,” accessed at http://smallstatebighistory.com/newport-gardner-fromslave-to-musical-composer [13] Hartigan-O’Connor, The Ties That Buy, 84-85 91-92, and 103-107. Mary Cowley does not seem to have left account books. [14] Newport Mercury, Oct. 15, 1764; Van Winkle Keller, Dance and Its Music, 389-400; Newport Mercury, Nov.11 and Dec. 19, 1763, Oct.15,1764, Oct.28, 1765, July 21 and Aug.11,1766, Sept. 26,1768, and Oct. 10,1768. [15] “The Last Will of James Honeyman (1710-1778) of January 16, 1778, Newport, RI” in Abraham van Doren Honeyman, The Honeyman Family in Scotland and America 1548-1908 (Plainfield, NJ: Honeyman Publishing, 1909), 89-90. The will gives the bounds of Mary Cowley’s location on Church Lane. Among her neighbors on the block south to Mill Street were tailors, ferrymen, gunsmiths, mariners, merchants, and Trinity Church’s Anglican minister. [16] Hartigan-O’Connor, The Ties That Buy, 50. The ideal assembly hall was twice as long as it was wide. In 1780, General Rochambeau held many dances at the Vernon House located still at 46 Clarke Street in Newport, the home of Newport merchant William Vernon, where there were eight rooms eighteen feet long and between fourteen and sixteen feet wide. James Center Swan (1811-1898) saw the building in his lifetime and wrote of it in “Historical Notes,” Newport Mercury, not dated, cut out and pasted into Stanhope’s Scrapbook N: 43, NHS. Also, George Champlin Mason (1820-1894) wrote about this house in Reminiscences of Newport (1884). [17] James N. Arnold, ed., Vital Records of Rhode Island 1636-1850 (Providence: Narragansett Publishing Co., 1891-1912), vol. 10, no. 4, 446, 453; John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 3 (Providence:1856-1865), 420; George Champlin Mason, Annals of Trinity Church, Newport, Rhode Island, 1698-1821 (Newport: Hammett, 1891), 52, 62, 69, 107. The date of 1741 for Mary Cowley’s mother’s death is based on her father’s remarriage. Since there is no burial for Elizabeth, she may have died in the smallpox epidemic of 1739, when infected residents were isolated on Goat Island and, if they died, were buried there. [18] Proceedings of the General Assembly June 1733, Maritime Papers-Colonial Wars, C#0180 Admiralty Court Papers, vol. 1 (1726 – 1743), James Collingwood vs. Ship Oratava, July 9, 1740, pp. 3-25, Rhode Island State Archives; Land & Public Notary Records, vol 5, 3, July 1741, in ibid. Thanks to Ken Carlson at the Rhode Island State Archives for this information. Records of the Rhode Island Vice Admiralty Court 1716-1752, Dorothy S. Towle, ed (1936), reproduced at ibid. (Millwood, NY: The American Historical Association, 1975), 90-91. [19] Arnold, ed., Vital Records, vol. 10, 496. The four Dunbar children were Robert (born 1721), Elizabeth (born 1722), Mary (born 1726), and Ann (born 1729). Robert went to sea, Elizabeth married in Warwick, Ann married in Bristol. For more on the siblings of Mary Cowley, her husbands, her and children, see the forthcoming article by Cherry Fletcher Bamberg and Marian Mathison Desrosiers, “George Dunbar of Newport, RI and His Descendants,” Rhode Island Roots, Dec. 2024. [20] Van Winkle, Dance and its Music in America, 314-16. [21] The Rhode Island Historical Society has folders on Samuel Freebody and his friends who ran these parties. Carl Bridenbaugh, “Colonial Newport as a Summer Resort,” Rhode Island History, vol. 26 (Jan. 1933), 1, discusses the influence of vacationers on Newport society. [22] Arnold, ed., Vital Records, vol. 10, 528. Mary’s three children by Sweet were George (born in 1745), Elizabeth (born in 1753), and Mary (born in 1755). George went to sea, Elizabeth and Mary married and lived in Newport. [23] Howard Chapin, A List of Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors in King George’s War : 1740-1748 (Providence, Rhode Island: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1920), 64, 123-124, 127-129, and 161-162. [24] Will of George Dunbar, Feb. 10, 1754, proved Feb. 18, 1754, Case #A643, 5: 11-12, in Providence Wills, Providence City Archives. Thank you to Cherry Fletcher Bamberg for this source. [25] Arnold, ed., Vital Records, vol. 10, 464. In 1741, Joseph Cowley, about age 34, married seventeen-year-old Penelope Pelham, after her father’s death. She passed at about age thirty-two in about 1756. Arnold, ed., Vital Records, vol. 10, 444 and 479. [26] The baptism of Rosalia Cowley is in Arnold, ed., Vital Records, vol. 10, 493. [27] Marian Mathison Desrosiers, The Banisters of Rhode Island in the American Revolution: Liberty and the Costs of Loyalties (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2021), 52,126, 215, and 250. See also Desrosiers, Banister of Newport, 210 n37. Mary’s teaching may have started earlier than the first issue of the Newport Mercury in 1758. [28] Will of Joseph Cowley of Newport, 1762, presented to the council April 1762, Newport Town Council Records, vol. 13, 144, Newport Historical Society. The British sailed the Town Council Records to New York but returned them to Newport waterlogged and torn. Cowley listed investments in the Canary Islands, Jamaica, the Bahamas, and South Carolina. Thanks to Bert Lippincott for this will. We have no probate record or burial information. [29] Existing Newport Mercury advertisements for rooms at her inn are in issues Oct. 24,1768, Jun. through Aug. 1774; May 1780 and May 1782; Jan. through Mar. 1783; Jul. through Oct. 1783; Sept. to Oct. 1784; Jan. through Feb. and Apr. to Jun. in 1786; Sept. to Oct. 1787 and Jun. 1788. Thomas Durfee, “Gleanings from The Judicial History of Rhode Island,” No. 18 in Rhode Island Historical Tracts (Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1883), 17-20. In 1747, the state created Bristol County for the towns of Barrington, Bristol, and Warren. In 1750, Rhode Island created Kent County for Coventry, West Warwick, and East Greenwich. [30] Mary Cowley Probate Records, April 2, 1792, vol. 2, 227-228, Newport City Hall. Thank you to Christina Alvernas for this information. Sharon V. Salinger, Taverns and Drinking in Early America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2002), 154. Rhode Island towns sold liquor licenses for 40 shillings with reapplication yearly, to men and occasionally to women who owned taverns. However, individuals could apply for a license for special events, such as upon an ordination of a minister, lottery selection, militia training, or a community celebration. [31] Cherry Fletcher Bamberg, “1774 Census of Rhode Island: Newport (Part 2), Rhode IslandRoots, Vol. 35, No. 2 (June 2009), 86. Two adult women are noted in the census with Mary. In 1774, Arabella Cowley was aged twenty-two and Mary Sweet was nineteen. Jay Mack Holbrook, Rhode Island 1782 Census [hereafter RI 1782 Census] (Oxford, Mass.: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979), 38. In 1782, Arabella was thirty and Rosalia Cowley was twenty-two.

[32] David Hildebrand, “George Washington and the Dance” (Jan. 2023), accessed at www.mountvernon.org. War did not stop the tea parties, garden walks, or picnics in the glen by members of British, American, and French armies in the cities they occupied. [33] Carl Bridenbaugh, Peter Harrison (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1949), 159. The story of Elizabeth Harrison joining General Percy at the dance is in the Van Buren Papers of her descendants. Elizabeth Pelham was seventy-one and the sister of Penelope, Joseph Cowley’s first wife. See also Frederick Mackenzie, Diary of Frederick Mackenzie: Giving a Daily Narrative of his Military Service as an Officer of the Regiment of Royal Welch Fusiliers During the Years 1773-1781 in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931), 234 and 237 (recording a similar party on January 19,1778, for Queen Charlotte’s birthday). [34] Newport Gazette, May 1 and 8, and Dec. 26,1777. Just before the British occupation of Newport, editor Solomon Southwick moved the printing of the Newport Mercury to Attleboro, Massachusetts; the British took over his Franklin printing press and published the Newport Gazette. [35] Margaret Champlin, aged seventeen, daughter of Margaret and Christopher Champlin, Newport merchant, danced that night. She was not only beautiful but spoke French. After the French left Newport, she married Dr. Benjamin Mason. Her grandson, George Champlin Mason, included this story in his book, In a Series of Pen and Pencil Sketches (Newport, RI: C.E. Hammett, 1875) 78-81, saying that she opened the ball with the General. Van Winkle points out that would have been highly irregular as the most honored lady of the town would have danced first with the General. Champlin likely led the first dance after intermission. The Town Council Records Feb 1781, p. 17 at NHS described the purchase of candles for all residents to put in their windows. Edwin Stone, in his Our French Allies, Rochambeau and His Army, Lafayette and His Devotion (Providence: Providence Press, 1884), 266, provides the Champlin genealogy and a description of her by French officers. None of the officer’s journals detail the specific event and there is no newspaper account. Captain Berthier (1753-1815) wrote about the town’s greeting for General Washington with “illuminations” in the windows of homes. [36] Newport Mercury, Nov. 16,1782. Mount Vernon’s website, at www.mtvernon.org, has information about the military leadership of the war. Prince Victor de Broglio (1756-1794) was a soldier in Rochambeau’s army, later a member of the French Revolutionary Assembly. During the Reign of Terror, he suffered death by the guillotine. He described Miss Brinley as “a rosebud” and Polly Lawton (a Quaker) as a “goddess of grace.” “Other Belles of Newport” were the sisters Anthony, Channing, Easton, Hunter, Robinson, Wanton, and Vernon. See The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783, translated and edited by Howard C. Rice Jr. and Anne S.K. Brown, vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 59. Marquis de Segur (1753-1830) served as a colonel and then a diplomat to Russia in the 1780s, and supported Napoleon and the Revolution of 1830. In his memoirs, he complimented the people of Newport, as “polite without ceremony and well-informed while devoid of affectation.” Comte de Vauban (1754-1815) was Rochambeau’s aide de camp and would be imprisoned at the Temple in Paris in 1806. Baron de Vioménil (1728-1792) was a major general and second in command to Rochambeau. He returned to France and died defending the King. [37] Advertisements in Newport Mercury, May 6,1780; Nov. 16,1782; Jan. through Mar. 1783; July 19 and 26, August 2, Oct. 11 and 25, 1783. Jun. to Aug. 1783, Oct. 1786, Jan. through Mar. 1787, Aug. 1787, Jan. 1788. Mary Cowley states she has been teaching for twenty years. Redwood Library and Athenaeum. The collection is there for the 1780s. [38] Newport Mercury, Jan.20, Apr.27, and Oct. 9,1786. [39] Newport Mercury, Sept. 4,5, and 11,1769, Apr. 20,1772, Aug. 9,1773, Jul. 1780, and Aug. 21,1788. [40] Arnold, ed. Vital Records, vol. 10, 538. [41] “Dancing School,” Newport Mercury, Jan.14,1794, Mar.19,1799, Dec.22, 1801, and Jan. 5,1802; “To Be Let,” Newport Mercury, July 2,1808. Thank you to Cherry Fletcher Bamberg for this information. [42] Hartigan-O’Connor, Ties That Buy, 195. Vendors of shoes, gloves, textiles, and candles saw business increase from consumers among the dancing crowd. [43] Van Winkle Keller, Dance and its Music, 400, index. One competitor, Abigail Stoneman, held dance assemblies but did not teach. Van Winkle examined eighteenth century newspapers from all thirteen colonies/states and found records of only sixteen women dance masters, nine of whom taught in Pennsylvania. They were wives or sisters of the male dance instructors. Accordingly, Mary Cowley was unique.