Queen Elizabeth II was a frequent visitor to the United States, sometimes quietly to visit horse-breeding farms in Kentucky, and sometimes publicly representing her country. She came twice to the Williamsburg, Virginia area, fifty years apart, in order to speak at the 350th and 400th anniversaries of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, the first permanent English settlement in North America. She also came to Virginia in July 1976 during the U.S. Bicentennial, when she made a five-day visit to the United States. Her schedulers gave her one day off in that time and asked her what she wanted to do. “I want to go to Monticello,” she replied. “I am full of admiration for what Thomas Jefferson achieved.”

The Queen was scheduled to visit historic Newport, Rhode Island, during her July 1976 visit, to dedicate Queen Anne Square, a park around beautiful Trinity Church, built 1723. I then lived in Newport and sang in the choir at Trinity Church, so that is where I met the Queen.

Queen Elizabeth II, on one of several tours to the United States. Here she meets Duke Ellington (American royalty!) in 1958 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

In 1970, I had raised the money and built a full-size, operational copy of the 24-gun Royal Navy frigate Rose so that people could see what a Revolutionary War ship looked like in the Bicentennial. After a successful sixteen-year career of one-week adventure sail-training cruises commanded by Captain Richard Bailey, the ship starred with Russell Crowe in “Master and Commander,” and she is now on permanent display at the San Diego Maritime Museum. Back in 1976, she was on display in Newport.

Queen Anne Square was a redevelopment project, which involved demolishing a number of relatively recent, ugly buildings. One of those buildings had been a laundry with a 75-foot-high black iron smokestack, bearing giant green neon letters, “Egan’s.” The former owner of the building, smelling a chance to make even more money from having sold the property to the Redevelopment Agency, obtained an injunction against the demolition of the building until he was paid much more money. The Redevelopment Agency refused to play ball.

That brought us to less than two weeks before the Queen was due to arrive aboard the Royal Yacht Britannia. To my eye, that black smokestack symbolized a middle finger aimed at the Queen. Fortunately, most of the world’s Tall Ships were visiting Newport for a few days before sailing off to New York City for Operation Sail that would take place on July 4th. I consulted crewmembers of the British sail-training vessel Sir Winston Churchill to see if they would help me to pull down the smokestack in the middle of the night. They agreed to do it, but a spectacular and dangerous thunderstorm broke out just as we were assembling, and the next morning the Tall Ships sailed away to New York – with that smokestack still standing.

I then asked Richard Bailey and other crewmembers of the Rose if they could help. I had tickets to attend the Queen’s dedication, and I offered Richard one of the tickets as an incentive. We assembled after midnight with bolt-cutters to clip the guy-wires holding up the smokestack, and two units of blocks-and-tackles that we could attach to a nearby tree in order to pull the stack over. The bottom of the stack was clearly rusted through, so we were able to pull the stack over to an angle of about thirty-five degrees, but it would not go any further before daylight, so we departed in a gentle rain. If the stack were to fall, it would fall only on the empty building, so we felt confident that no one was at risk of injury.

A neighbor, who later said he was in favor of removing the smokestack, telephoned the local police, the state police, the FBI, and the Secret Service, claiming that it was all an Irish Republican Army plot to kill the Queen.

Richard walked over from the Rose to see what was happening. The neighbor pointed him out to police, so Richard was hauled off to the police station under arrest. The police wanted to know who else was involved, but Richard would not say. Finally, Richard offered to make a telephone call to see if someone else (me) would come and talk to them. When I showed up minutes later at the police station, a few of the police welcomed me with open arms, because I had only just given them good grades for a college course I had taught them about local history.

The police quickly told me that they completely approved of my efforts to destroy the smokestack, but they said that the FBI and Secret Service were very concerned, and I would have to be interrogated by them, as well as have mug-shots and finger-prints taken. Several federal officers with biceps as large as my thighs, wearing three-piece suits, walked up and down in front of me, asking such things as, “How long have you hated authority figures?” and “How long have you wanted to kill the Queen?”

After what seemed hours, they said, “Maybe we believe you, and maybe we don’t, but we’ll be watching you, and if you take one step towards the Queen, we shoot first and ask questions later.” They added that Richard and I would be added to their list of potential assassins, but if we behaved for seven years we would be dropped from the list.

On Saturday, July 10, the Queen, accompanied by her husband Prince Philip, landed at T. F. Greene Airport. Their motorcade made its way down Route 95 to Route 4 and ultimately over the Jamestown and Newport bridges. Her Majesty then waved at spectators lining the streets along Washington Street, Long Wharf, America’s Cup Avenue, Memorial Boulevard, and Spring Street, ending at Trinity Church, where the dedication occurred at about 6 p.m. Later in the evening the Queen and Prince Philip dined with President Gerald Ford and his wife, Bette, on board the Royal Yacht Britannia in Newport Harbor.

Richard and I were presented to the Queen, and some of the spectators must have been confused, as the Secret Service officers greeted us both by name.

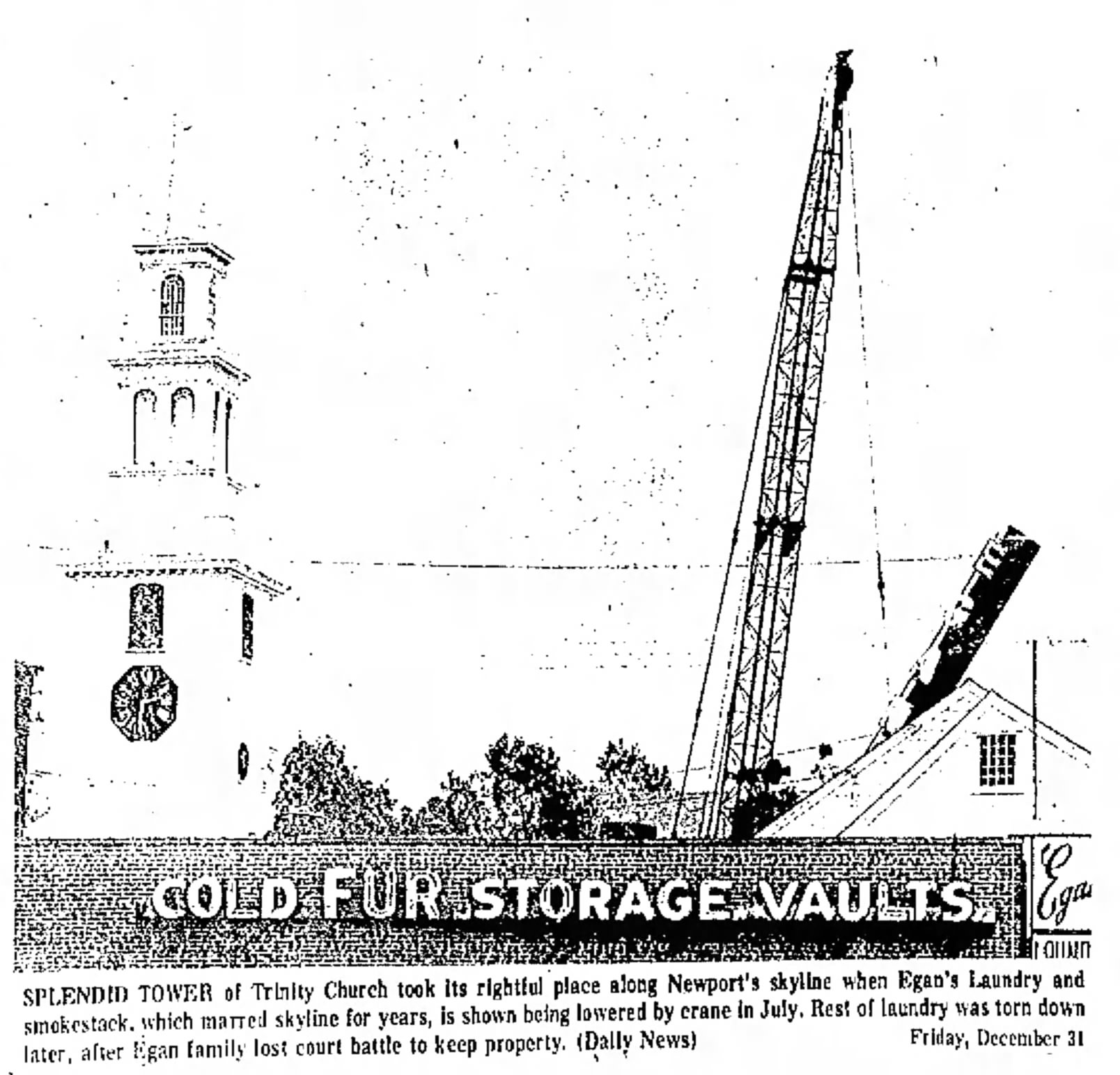

Unfortunately, the smokestack was not removed before the Queen’s visit to Trinity Church. But within a week, a local judge quickly ruled that in spite of the restraining order the stack must be removed as a public safety hazard. About mid-day on July 15, a giant crane arrived.

Trinity Church, founded in 1698, the oldest Episcopal parish in the state. From this aerial view, to the left of the church remains crowded with buildings, before the current open and charming Queen Anne Square was dedicated by Queen Elizabeth in 1976 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections).

The matter was written up in a local newspaper. The July 16 edition of the Newport Mercury reported:

“Trinity Church no longer has any competition in the Newport skyline.

The smokestack rising about the old Egan’s laundry plant on Thames Street was taken down yesterday afternoon after vandals cut some of the cables holding it in place.”

The newspaper ended the article:

“The Newport police took one person in for questioning and then released him. A police spokesman said the incident was not directed against the Queen.

‘Actually, it was the nicest thing that could have been done for her visit,’ one eyewitness said.”

In 1980, I moved to Williamsburg for graduate study at William & Mary, and I immediately joined the choir at Bruton Parish Church. You can imagine my apprehension when I learned that the G-7 meeting of World leaders was being held in Williamsburg and the Bruton Choir was asked to sing for the dignitaries. Would I be arrested instead? Luckily, no such thing happened.