In the beginning of the 1993 movie Gettysburg, Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain of the Twentieth Maine receives orders assigning 120 men of the Second Maine Regiment who had recently been mustered out of service to his own regiment. In the movie, Chamberlain is told that he could shoot any man “who refuses to do his duty.” The 120 men from the Second Maine, declared to be mutineers, are marched to the camp of the Twentieth Maine under armed escort. Upon their arrival in camp, Chamberlain gives an impassioned speech about preserving the Union and Emancipation. The men of the Second Maine are so taken by the speech that 114 of them vote to pick up their muskets and join the Twentieth. The remaining six remain under guard, but they redeem themselves two days later on Little Round Top. Much of the history of this incident was dramatized for the movie, and the true story of the merger of the Second and Twentieth Maine is much more complex. However, in the movie, Jeff Daniels, playing the role of Chamberlain utters, “Mutiny. I thought that was a word for the Navy!” Mutinies did occur on land as well during the Civil War. One of these involved the Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers in the summer of 1862.[1]

Recruited from throughout Rhode Island in August and September of 1861, the Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers would earn a reputation as a solid, dependable infantry regiment, but would not rise to the fame of other Union units such as the Iron Brigade, Excelsior Brigade, Vermont Brigade, or the Twentieth Maine. Indeed, these Rhode Islanders in time would eventually become nearly totally forgotten by their own state, overshadowed by the deeds of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers and the First Rhode Island Light Artillery.[2]

Rhode Island governor William Sprague had to appoint the commander of the Fourth. He appointed Justus I. McCarthy, a tough, old Army regular and Mexican War veteran. McCarthy was welcomed by the men of the regiment. He worked hard to train the raw recruits of the Fourth into a disciplined unit.

After only a few weeks of command Colonel McCarthy had a falling out with Governor Sprague and resigned. Sprague quickly promoted Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Peace Rodman to become colonel of the Fourth. A mill owner from Peace Dale in South Kingstown, Rodman was a devout Baptist (and not a Quaker as has been often quoted, as a result of his Quaker-sounding middle name). He was also active in politics and prior to the war had served as the commander of the Narragansett Guards, a militia unit. The Narragansett Guards became Company E of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers with Rodman as captain. On the morning of July 21, 1861, Rodman’s men fired the first infantry shots at the First Battle of Bull Run. Performing well in the battle, Rodman was promoted and transferred to the Fourth.[3]

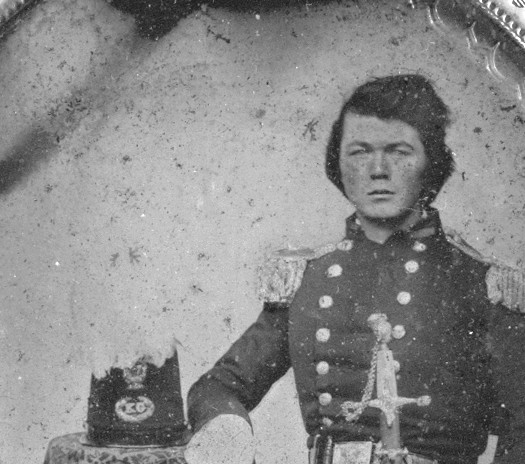

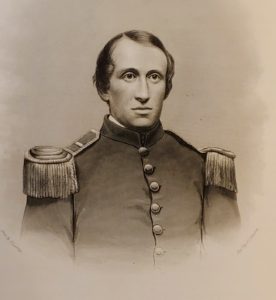

The promotion of Isaac Peace Rodman of South Kingstown to brigadier general set off the chain of events that led to the mutiny in the Fourth Rhode Island. He was mortally wounded at Antietam leading a division (RG Collection)

As the new lieutenant colonel of the Fourth, Sprague selected George W. Tew of Newport. A brick mason, Tew had served as the commander of the Artillery Company of Newport before the war. The first man from Newport to volunteer for the Union Army in August 1861, Tew led the Artillery Company of Newport to war as Company F of the First Rhode Island Detached Militia. After being mustered out in August 1861, Tew again reentered service as captain of Company G of the Fourth Rhode Island, composed of men from Aquidneck Island. His commission as lieutenant colonel of the Fourth Rhode Island was dated November 11, 1861.[4]

Rodman and Tew trained their men hard for service at the front. In December 1861, the Fourth was assigned to the Coast Division, forming at Annapolis, Maryland. Commanded by fellow Rhode Islander Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside, the Coast Division was composed largely of men from the New England states. Soon they were all bound for the North Carolina coast. On February 8, 1862, the Fourth took part in the fighting at Roanoke Island.

Five weeks later on March 14, the Fourth fought in the Battle of New Bern. Advancing to support the Twenty-First Massachusetts, which was bogged down, Rodman ordered the Fourth to fix bayonets and charge the Confederate fortifications. The Rhode Islanders gave “three cheers and a Narragansett,” and vaulted over the Confederate earthworks, capturing Latham’s North Carolina Battery. The charge split the Confederate line in two, allowing Union forces to exploit the breech and rout the Confederate defenders.

In his after action report, General Burnside singled out the exploits of the Fourth and praised Rodman for courage in leading the assault. The Fourth suffered moderate losses: sixteen dead and twenty wounded. Colonel Rodman was among the wounded, slightly injured.

A month after the capture of New Bern, the Fourth was again in action, taking part in the siege and capture of Fort Macon. Burnside’s campaign on the North Carolina coast had been a success.

As one of the first decisive Union victories of the war, President Abraham Lincoln sought to reward those who had participated in the Burnside Expedition. Burnside, together with his three brigade commanders (Jesse Reno, John Foster, and John G. Parke) all received promotion to major general.

Among those given their first star as a brigadier general was Isaac Peace Rodman of the Fourth; his commission was dated April 28, 1862. Rodman found out about the promotion in June, as he recovered from a severe attack of typhoid at home in South Kingstown. Quickly donning the new uniform of his rank, Rodman received orders to remain in Rhode Island throughout much of the summer of 1862 and assist in recruiting efforts.[5]

Meanwhile, in Beaufort, North Carolina, Lieutenant Colonel Tew handled the day-to-day affairs of the Fourth Rhode Island, which assumed garrison duty in the city. Receiving almost daily mail delivery from Rhode Island, Tew was certain that the mail would soon bring him his commission as colonel of the Fourth Rhode Island. However, on June 30, several regiments at New Bern, including the Fourth, received orders to head north as reinforcements to McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, then in full retreat during the Peninsula Campaign. By mid-July, these regiments, which later formed the nucleus of the Ninth Corps, were encamped near Newport News, Virginia. The men, many of them hailing from towns surrounding Narragansett Bay, greatly enjoyed the opportunity to harvest oysters and swim daily. Soon a surprise visitor to the regiment arrived in camp and darkened their moods.

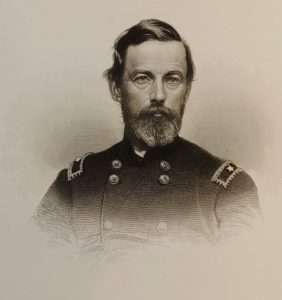

A highly respected officer from Newport, Lieutenant Colonel George W. Tew was passed over promotion. He later became colonel of the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. RG Collection.

Civil War regiments, particularly the companies composing those regiments, were recruited in the same community. Company D of the Fourth Rhode Island, for example, was composed of men from the rural northwestern Rhode Island towns of Glocester and Burrillville. Company D included a dozen men from the southern town of Hopkinton. They were assigned to Company D after Hopkinton failed to raise its own company for the regiment. Originally cast down as “The South County Boys” by their northern neighbors, the men from Hopkinton eventually blended in and were accepted by the regiment’s soldiers from the northern part of the state.

Typically, when men were promoted to non-commissioned officer rank, such as sergeant, they remained in their own company. By contrast, newly commissioned offers were often assigned to another company to make up for a casualty sustained by death or resignation.[6]

Men who stood shoulder-to-shoulder marching into combat, oftentimes surrounded by relatives and neighbors, placed great trust in their officers, who often led from the front. Indeed, Union lieutenants and captains suffered the highest casualty rate of any group during the war. Almost exclusively, these officers were men who had proven themselves in combat, serving in the same regiment that they now commanded. When an outsider was assigned to a regiment as a replacement officer, it often threatened the very core of the regiment. These outsiders, some of whom had never seen combat before, were often political appointees who did not understand the men they were being assigned to command.[7]

With Rodman now wearing the stars of a brigadier general, Lieutenant Colonel Tew eagerly awaited his own promotion. Corporal George H. Allen, who served in Company B of the Fourth, wrote of Tew, “He was a man very well liked by the entire regiment, and nothing would have pleased us better than to see him wear the silver eagle as our commander.” Unfortunately, Lieutenant Colonel Tew would not wear silver eagles in the “Fighting Fourth,” a moniker given to the regiment by the Providence Journal after its participation in the Burnside Expedition.[8]

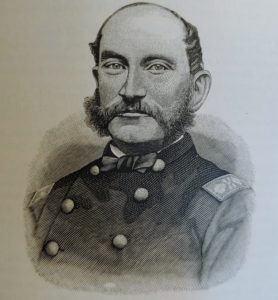

On August 1, 1862, a man no one had ever seen in the Fourth Rhode Island suddenly appeared in camp wearing the eagles of a colonel. He was William H.P. Steere. Originally from Providence, Steere had years of service before the war in the National Cadets, a militia company. When the war began, he recruited in Providence a company, which became Company D of the Second Rhode Island. This company included the famed diarist raised in Pawtuxet, Elisha Hunt Rhodes. Rhodes respected Steere, whom he declared to be “all right.” Captain Steere led his men into action at Bull Run, much like Rodman had done, and was promoted for his efforts. With the battle deaths of Colonel John Stanton Slocum and Major Sullivan Ballou, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Wheaton was promoted to colonel of the Second Rhode Island and Steere became its lieutenant colonel. Steere’s commission was dated July 22, 1861. With silver oak leaves on his shoulder, Steere led his men throughout the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, until his promotion to colonel and reassignment to the Fourth, with a commission dating to June 12, 1862.[9]

Colonel William H. P. Steere of Providence was the reason for the mutiny. He redeemed himself through his battlefield leadership at Antietam, where he was severely wounded. RG collection.

The appearance of Colonel Steere in camp was met “with much displeasure.” When Steere appeared in camp, Captain Jeremiah Brown of the Fourth was the regiment’s officer of the day. As such Brown was responsible for guard mounts, pickets, and other duties in the camp. When the new colonel approached Brown to inquire of the state of the regiment, Brown swore that he would not take any orders from Steere, and would not serve under his command. Colonel Steere promptly sent charges of insubornation to Burnside’s headquarters. Captain Brown was instantly dismissed and cashiered from the service.

Walking among the camp of the regiment, Steere was met with hoots and swears from both officers and men. That evening, he called the regiment out for dress parade. For months, the men of the Fourth had been used to Lieutenant Colonel Tew leading the regiment for the daily parade. This time, Tew took his subordinate place in line, rather than in front of the regiment. Corporal Allen wrote, “To see him who, since Colonel Rodman relinquished command, had held his position in front of the regiment, give way now to a perfect stranger, a man whom we knew nothing of us, was more than we could stand.” Tew promptly responded to Steere’s orders, taking his place in line without grumbling. But Tew did little to stop the feelings of discord harbored by the men in the Fourth.

As Colonel Steere attempted to lead his men through the manual exercise at dress parade, many of the officers and men refused to follow his orders, did not properly execute the movements, or simply stood there. Finally Steere had had enough, he stated that Governor Sprague had ordered him to command the regiment, that he was simply following orders, and that he would not resign. Steere dismissed the disgruntled men, who returned to their tents. One member of the Fourth wrote, “A storm was brewing in camp. It needed but one more incentive to create an eruption.”[10]

That eruption was caused by alcohol. At the time the parade was being dismissed, boxes from Rhode Island were being distributed to the men of the Fourth. Oftentimes these boxes were inspected for liquor, and any located was promptly seized (and often drank by the officers). This time, however, the boxes were not inspected, allowing the alcohol to enter the regimental camp. Soon “most of the men” in the regiment were quite intoxicated, especially those of Company E, composed of men from Smithfield.

Captain Martin Buffum was the new officer of the day and with his guard he tried his best to quiet down the men of the regiment and order them into their tents. The men were soon “singing and howling” quite loudly, and then attacked Buffum and his guard with sticks and old army boots, forcing them to retreat. Colonel Steere came out of his quarters and tried to arrest the ringleaders. After being hit in the head a few times, the “worst of them” were arrested, and the Fourth’s camp quieted down for the night.

The next morning, August 2, Steere ordered the regiment to fall into line and prepare to leave Newport News. The officers and men of the Fourth again refused to follow his command. That morning the Eighth and Eleventh Connecticut Regiments that formed part of the same brigade as the Fourth were paid off. Colonel Steere refused, however, to allow the paymaster to pay off the Fourth until they were onboard the ship that would transport them, as he feared they would use the money to buy more alcohol. Colonel Steere now had a real mutiny on his hands: the officers and men of the regiment refused to march and simply stayed in camp.

General Burnside, hearing of the mutiny, ordered the Eighth Connecticut to surround the camp and force the Fourth onboard the steamer. The men of the Eighth refused to march. The Ninth New York, a Zouave unit under the flamboyant Colonel Rush C. Hawkins, was also ordered to the Fourth’s camp; they likewise refused the orders. Finally, Steere ordered the regiment to be paid. The men received their money and promptly boarded the steamer West Point, which brought them to a new camp at Falmouth, Virginia.[11]

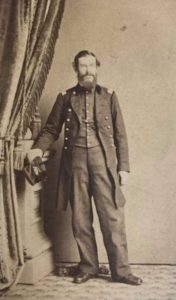

At Falmouth, yet another act of insubornation took place. On August 4, the officers of the regiment held a meeting and decided, en masse, to resign their commissions rather than serve under Steere. Joseph B. Curtis, who had originally been adjutant of the Fourth, but was now a captain serving on General Rodman’s staff, went to the regiment to try and tell his friends to not take this course of action. Captain Curtis spoke to the officers, “If you feel wronged, it is still your soldierly duty to submit to your superior officers; and why, to revenge your own griefs, should you wrong the country by unofficering the regiment, and making it more inefficient than a new one, by leaving in it heart-burnings and jealousies?” Despite Curtis’s best efforts, the officers remained determined to resign.

Lieutenant Colonel Joseph B. Curtis urged restraint among his fellow officers in the wake of the promotion of Colonel Steere. He was killed at Fredericksburg in December 1862. RG Collection.

In Providence, Governor Sprague, after hearing about the incidents at Newport News, took the unusual step of traveling south to deal with the matter first hand. Embracing his role as “captain general” of the state militia, Sprague took a deep, personal interest in the Rhode Island regiments that he raised.

On August 11, Sprague met with Burnside. They decided, for the good of the regiment, to accept the resignation of the officers and to commission new officers from the ranks. Half of the officer corps of the Fourth resigned that day, stripping the regiment of invaluable leadership that had been trained in the hard fought North Carolina Campaign. The officers to resign were: Lieutenant Colonel George W. Tew; Major John A. Allen; and Captains Israel M. Hopkins, Nelson Kenyon, Erastus E. Lapham, Henry Simon, and William C. Wood; First Lieutenants Charles W. Munroe and Walter E. West; and Second Lieutenants Otis A. Baker, Albert N. Burdick, John E. Drohan, Jabez S. Smith, and Henry L. Starkweather. The officers quickly bade farewell to their men and left for Rhode Island.

Lieutenant Otis Barker of Company A was one of the many Fourth Rhode Island officers to resign. Library of Congress.

After meeting with Burnside, Governor Sprague decided to visit the Fourth’s camp. The governor was greeted with a barrage of hardtack and potatoes, along with “groans, jeers, and hootings.” Following a lengthy meeting with Colonel Steere discussing the state of the regiment, and the promotion of men from the ranks to replace the officers who had just resigned, Sprague left camp to return home.[12]

That night, Colonel Steere finally got the Fourth Rhode Island under his command. Forming a hollow square, with Steere in the middle, Steere stated that he hoped now that the recalcitrant officers were gone that matters would return to normal. A list of new officers, most of them promoted from the regiment’s sergeants, were also read. Captain Curtis of Rodman’s staff was introduced as the new lieutenant colonel of the regiment. The promotion of these sergeants, along with Curtis, a respected, skilled officer who had been a civil engineer before the war, helped to steady the nerves of the men. Steere knew the Fourth was composed of good material and did not want a few “bad apples” to spoil the good reputation that the regiment had earned in North Carolina. Finally, the colonel stated he hoped “his experience with them would be a source of lasting pleasure to him during his life.” Steere then dismissed the men.[13]

The next day, August 12, it appeared as though nothing had ever happened in the regiment. The new officers assumed their positions and the regiment went out on picket, performed drill and did guard duty. According to one observer, “the discipline and routine of duty progressed without further duty.” By removing the mutinous officers and promoting men who had already earned the respect of the enlisted men in the Fourth, Steere was able to cement his control over the regiment.

Corporal George H. Allen wrote in his memoirs of Colonel Steele:

In his subsequent course of action, and by the kindness and the fatherly care he manifested towards us, the old colonel at last won the respect and esteem of the whole regiment, and they were willing to do his least bidding, and ready to follow him anywhere in the face of death he might lead them. Never did such a change of heart toward any one man occur as was experienced in time by that regiment, and there is not a man living to-day of the veterans of that old rough and ready Fourth Rhode Island but loves to honor the name and revere the memory of our faithful old colonel, William H. P. Steere.[14]

While Colonel Steere won over his men on the parade ground, he was still unproven with the Fourth in combat. His chance came on September 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam. Forming the extreme left flank of the Army of the Potomac, the Fourth plunged ahead into a forty acre cornfield on the farm of John Otto. In the dense corn, Colonel Steere could not see what was in front of him. Soon the men of the Fourth encountered men to their front wearing blue uniforms and carrying what appeared to them to be the United States flag. In actuality, these troops were South Carolinians from Gregg’s Brigade wearing captured Union uniforms from Harpers Ferry, while the flag was the Stars and Bars, which bore a resemblance to the Confederacy’s Stars and Stripes.

A heavy volley erupted to the front of the Fourth, leading Steere to realize these men were Rebels. Pinned down in a slight depression, Steere knew that the Fourth had to charge up a rise of ground to drive back the enemy. The colonel instantly earned the respect of those who still doubted his ability through his leadership at Antietam, as he calmly walked the line, encouraging his men. The Sixteenth Connecticut was on the right flank of the Fourth. A green regiment, fresh from Hartford, the soldiers of the Sixteenth had barely been given anytime to familiarize themselves with the tactics of the day; indeed after the war, some veterans would go so far as to claim they had never been taught how to load their muskets. After firing a disjointed volley, the men of the Sixteenth panicked and fled to the rear, leaving the Fourth alone and unsupported. Tragically, General Rodman, who was that day commanding the Third Division of the Ninth Corps, attempted to lead the Eighth Connecticut to the relief of the Fourth, but was shot in the chest and mortally wounded.[15]

Alone and with no other support, the men of the Fourth were receiving fire from an entire brigade of South Carolinians in both flanks and their front. Newly-commissioned Second Lieutenant Henry Joshua Spooner recalled, “We were left alone, nothing to the right of us, nothing to the left of us. The hot fire continued on both sides, the hottest I ever encountered, the bullets whistling around us like hives of loosened bees.”

Colonel Steere went down with a severe, painful wound to the hip. For his heroism that day, he was later awarded the brevet of brigadier general.

Soon the Confederates gained the left flank of the Fourth. Corporal George H. Allen stated, “Our men fell like sheep at the slaughter.” “The Rebels, seeing our predicament, determined to wipe us out,” recalled one veteran of the Fourth. Lieutenant Colonel Curtis attempted to charge the enemy line, but in the swirling fury of the cornfield, “amidst a confused babel of orders,” it appeared little could be done to stop the destruction of the Fourth.

Finally, the Fourth broke and ran to the rear, but later than night it reformed near Burnside Bridge. The Fourth brought 247 men into the fighting at Antietam. On that bloody day, the regiment lost 116 men, including 37 dead or mortally wounded.[16]

After Antietam, the Fourth went on to fight at the Battle of Fredericksburg, where Lieutenant Colonel Curtis was killed. In the spring of 1863, the regiment took part in the Suffolk Campaign.

Colonel Steere never fully recovered from his Antietam injuries. He held several administrative posts, and did lead a brigade at Suffolk, but spent much of his time recovering from his wounds. While the Fourth was sent to guard Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout, Maryland in late 1863, Steere remained near Yorktown, in command of a depot. In July 1864, the Fourth and Colonel Steere received orders to rejoin the Ninth Corps, then besieging Petersburg.

Colonel Steere’s last battle was in command of the Fourth at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. Advancing into the “horrid pit,” the Rhode Islanders, as well as thousands of other Union troops, were pinned down and trapped. The Fourth again lost heavily that day—one-third of the regiment went down. After the battle, stricken with severe dysentery, Steere returned to Providence where he stayed until mustered out in October 1864.[17]

After the disaster at the Battle of the Crater, the Fourth remained on the Petersburg line, taking part in the fighting at Hatcher’s Run and Poplar Spring Church. In October 1864, while the majority of the regiment returned to Rhode Island, some 226 officers and men who had reenlisted or had enlisted after 1861 remained in the field. Consolidated into a three company battalion, these men were combined with the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, a unit that had also lost heavily in the 1864 battles.

The consolidation with the Seventh did not sit too well with the veterans of the Fourth. They nearly mutinied again. They felt that they had earned the right to continue to be called the Fourth, the regiment they had enlisted in. Corporal George H. Allen proudly recalled in his memoirs, “We were once and always, the Fourth Rhode Island Regiment.”

Lieutenant Colonel Percy Daniels of the Seventh Rhode Island was equally despised by the men of the Seventh, as well as those of the Fourth. Daniels assigned the men of the Fourth to the most hazardous part of Fort Hell, which the Seventh was garrisoning in front of Petersburg, and demanded they perform constant picket and fatigue duty. When the men of the Fourth nearly mutinied again, Daniels finally backed down.

The consolidation with the Seventh was a bitter end for the men who were proud to call themselves the Fourth. After the war, although they were eligible, no member of the Fourth who had served with the Seventh joined the Seventh’s veteran association. Furthermore, to a man, they had engraved on their headstone that they had served in the Fourth, not the Seventh Rhode Island. Colonel Steere died in 1882.[18]

George W. Tew, the man whose lack of promotion caused the mutiny, returned to service almost immediately after his resignation from the Fourth. He recruited a company of men from Newport and was again appointed as a captain. This time, he was assigned to the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, then on garrison duty in North Carolina. Tew was subsequently promoted to major, lieutenant colonel, and colonel of the Fifth. As did Steere, Tew ended the war a brevet brigadier general.[19]

Was Governor Sprague right to select Steere a colonel of the Fourth Rhode Island over Tew? Both men had similar pre-war militia experience, were veterans of Bull Run, and had seen hard service (Steere on the Peninsula, and Tew in North Carolina during the Burnside Campaign). The crux was, however, in the details. Steere’s commission as lieutenant colonel was dated July 22, 1861, and Tew’s was dated November 11, 1861. In an army system where seniority, rather than experience, counted for everything, Steere technically was the senior officer and was therefore promoted to the position.

While Steere was the senior officer, his promotion to another unit greatly adversely affected the Fourth’s unit cohesion. Only after the problem officers were dismissed and he proved himself under fire at Antietam did Colonel Steere earn the respect of his men.

Did Governor Sprague learn from the August 1862 mutiny of the Fourth Rhode Island? No! He actually incited another incident, this time in the Second Rhode Island, in December of 1862 by promoting the regimental chaplain, Thorndike C. Jameson to major. As the chaplain was a staff officer, with no place in the regimental line, Sprague by-passed every officer in the regiment. Rather than mutiny, a few of the officers who felt slighted resigned and went home. Lieutenant Elisha Hunt Rhodes wrote of Jameson, “He is incompetent, and we do not want him with us.” Two weeks later, “Major Jameson has resigned. We are very glad to get rid of him, for we have had a constant quarrel ever since.”

Sprague had one last trick up his sleeve. In one of his last acts as governor, before resigning to serve in the United States Senate in March 1863, the governor appointed Jameson to major of the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. Jameson was eventually dismissed for incompetence in February 1865.[20]

The August 1862 incident involving the Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers is one of the few documented mutinies of the Civil War. In promoting an officer from outside of the regiment, Governor William Sprague had upheld the tradition of date of rank. But in doing so he upset the cohesion of a regiment that had earned a reputation for tough fighting in the Burnside Expedition. The officers of the Fourth, rather than attempting to help stop the insurrection, actually helped spur it on, adding fuel to an already volatile situation. Only after these officers were removed, and new officers appointed from the ranks, was Colonel William H. P. Steere able to assume true command of the regiment. Colonel Steere proved himself to the men of his new regiment, leading from the front, and suffering a severe wound at Antietam. Only after he had proven himself in combat was Steere respected as the colonel of the “Fighting Fourth” Rhode Island Volunteers.

[Banner image: The promotion of Isaac Peace Rodman of South Kingstown to brigadier general set off the chain of events that led to the mutiny in the Fourth Rhode Island. He was mortally wounded at Antietam leading a division (RG Collection)]

Notes:

[1] Ronald F. Maxwell, Randy Edelman, Tom Berenger, Jeff Daniels, Martin Sheen, and Michael Shaara. Gettysburg. Burbank, CA: Turner Entertainment, 1993.

[2] For a history and roster of the Fourth Rhode Island, see Robert Grandchamp, Like Sheep at the Slaughter: A Statistical History of the Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2018).

[3] Isaac Peace Rodman Papers and Journal of Patrick Lyons, South County History Center, Kingston, RI. Despite claims in nearly every biography that Rodman was a Quaker, this is a complete fallacy. His papers establish that Rodman was a devout Baptist.

[4] John Russell Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers, Who Were Engaged in the Service of Their Country During the Great Rebellion of the South: Illustrated with Thirty-Four Portraits (Providence, RI: Sydney S. Rider, 1867), 320-323.

[5] George Allen, Forty-Six Months with the Fourth R.I. Volunteers in the War of 1861 to 1865: Comprising a History of the Marches, Battles, and Camp Life (Providence, RI: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1887), 88-102; Charles F. Walcott, History of the Twenty-First Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, in the War for the Preservation of the Union, 1861-1865: With Statistics of the War and of Rebel Prisons (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin and Co, 1882), 59-80. On the Burnside Expedition to North Carolina, see Richard A. Sauers, “A Succession of Honorable Victories”: The Burnside Expedition in North Carolina (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1996).

[6] Kris VanDenBossche, “War and Other Remembrances,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 47, No. 4 (November 1989), 115-119. These are the edited and published memoirs of George Bradford Carpenter who served in the Fourth Rhode Island. The original typescript of the manuscript is held at the Westerly Public Library Special Collections.

[7] On this phenomenon, refer to Mark H. Dunkelman, “A Just Right to Select Our Own Officers:” Reactions in a Union Regiment to Officers Commissioned from Outside Its Ranks” Civil War History Vol. 44, No. 1 (March 1998), 24-34.

[8] Allen, Forty-Six Months, 124-125. Memoirs of R.I., 321-323.

[9] Elisha Hunt Rhodes, All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, Edited by Robert Hunt Rhodes (Woonsocket, RI: Andrew Mowbray, 1985), 1-25. Memoirs of R.I., 199-201.

[10] Allen, Forty-Six Months, 124-126; Newport Daily News, August 3-12, 1862; Providence Journal, August 3-12, 1862; VanDenBossche, “War and Other Remembrances,” 121-122.

[11] Same sources as in above note.

[12] Memoirs of R.I., 225-235; Allen, Forty-Six Months, 127-129; Regimental Descriptive Book, Fourth Rhode Island Volunteers and Resignation Letters to William Sprague, August 4, 1862, Executive Correspondence, Rhode Island State Archives.

[13] Memoirs of R.I., 225-235.

[14] Allen, Forty-Six Months, 128-129.

[15] VanDenBossche, “War and Other Remembrances,” 122-132; Memoirs of R.I., 233-235. Samuel Francis to “Dear Friends,” October 3, 1862, Varnum Armory Collection, East Greenwich, RI.

[16] Francis to “Dear Friends,” October 3, 1862; Providence Journal, September 25, 1862; Henry J. Spooner, The Maryland Campaign with the Fourth Rhode Island (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnum, 1903), 1-21; Joseph B. Curtis to Edward C. Mauran, September 22, 1862, Fourth Rhode Island Correspondence, Rhode Island State Archives.

[17] Memoirs of R.I., 203-206. Allen, Forty-Six Months, 200-309.

[18] Allen, Forty-Six Months, 309-329; William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War, 1862-1865 (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnum, 1903), 222-229; Papers of the Seventh Rhode Island Veteran Association, 1873-1921, Robert Grandchamp Collection.

[19] Memoirs of R.I., 320-324; Charles E. Douglas, 1863 and 1864 Journals, Robert Grandchamp Collection.

[20] Rhodes, All for the Union, 85-89; Henry T. Blanchard to Father, January 15, 1863, Robert Grandchamp Collection.