During the period when slavery was lawful in America, it is claimed that the underground railroad assisted more than 100,000 African-American slaves reach freedom. (The underground railroad was not a real railroad, but a secret system for escaped slaves to use to travel to freedom.) Some fugitive slaves escaped to Spanish Florida before it became a U.S. territory in 1821, while other fugitives found refuge among the indigenous tribes of the American South and West. Most fugitives, however, found their way from border states North over land by way of Pennsylvania and Ohio, or by sea into New York and New England, and then on to Canada. Rhode Island played a role in assisting some fugitives finding their way to freedom to the North. Little is written on this subject. This article brings to light an overlooked narrative by a man who as a teenager in Ashaway risked his own freedom to assist runaway slaves.

By its very nature the underground railroad was a secretive enterprise. The Compromise of 1850, with its Fugitive Slave Law, made it a crime punishable with a fine ($1,000) and a jail sentence (six months) for anyone aiding an escaped slave. Yet in Rhode Island, and elsewhere throughout the North, people aided in helping fugitive slaves find a way to Canada and freedom. Exactly how many will never be known.

There are places in Rhode Island that served as stations, where a slave could be harbored, fed, and clothed before moving along his or her way with the aid of a conductor to the next safe station. Sometimes the stops were for just a day. Most movement on the “railroad” was, for obvious reasons, conducted at night. Sometimes a slave would be held for a while until the next leg of the journey could be safely accomplished. In all instances there was an apprehension of being exposed. Not all northerners supported abolition. But Rhode Island was populated with a large number of Quakers, many of whom favored abolition, and others of different faiths, who were willing to work to get fugitive slaves to their promised land of freedom, their Canaan as it were.

The work of moving a slave to freedom from one stop to the next was a secretive venture so that today we know little of the “stations” along the underground railroad and even less of those “conductors” who assisted in this operation. A few are known. Perhaps the most famous of these operatives was Elizabeth Buffum Chace, daughter of Arnold Buffum, one of the founders of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Not all abolitionists were involved in the underground railroad but Arnold Buffum’s daughters, Elizabeth, and her husband Samuel, as well as Elizabeth’s sister, Sarah, and her husband, Nathaniel Borden, were all active in assisting runaways. This family ran slaves from their residences in Fall River, Massachusetts, to Valley Falls, a small village in the town of Cumberland. See Figure 1.

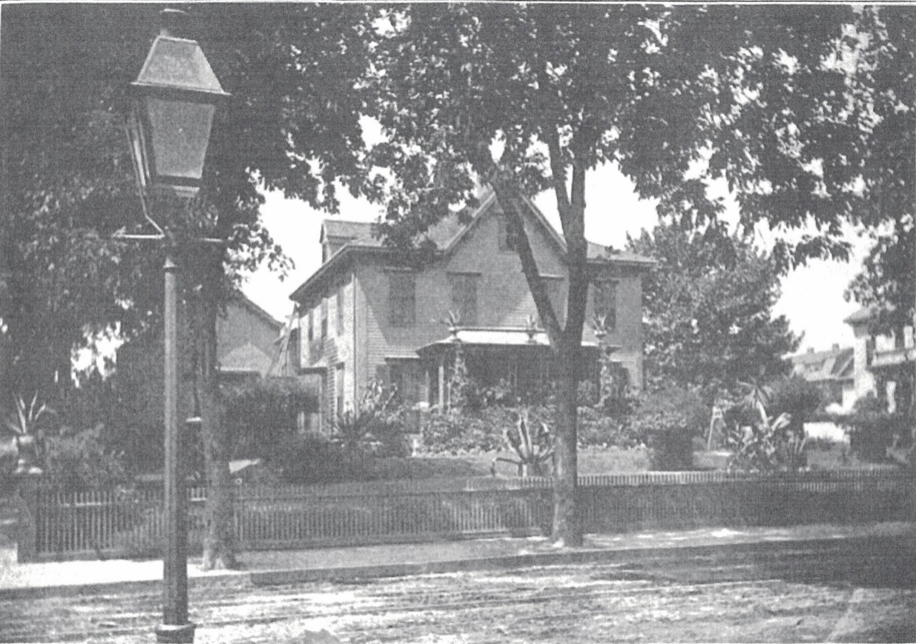

Figure 1 – A late 19th century view of the Elizabeth Buffum Chace house in Valley Falls (house no longer standing).

Other Rhode Islanders who aided fugitive slaves included the Quaker industrialist Moses Brown of Providence [1], Daniel Mitchell of Providence, Charles Perry of Westerly [2], George and Sarah Fayerweather, free blacks of Kingston, Jethro and Anne Mitchell of Middletown [3] and Isaac Rice, Sophia Little, and George Downing of Newport. The Rice house at the corner of William and Thomas streets in Newport served as a station on the underground railroad. Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Sojourner Truth are all known to have stayed at the Rice house when lecturing in Rhode Island. In 1838, when Frederick Douglass escaped from bondage in Maryland, he came through Newport on his way to New Bedford. While we do not know where he stayed, he could have sought shelter in the Isaac Rice house. See Figure 2.

Other places that served as stations on the underground railroad included the Bethel AME Church in Providence and the Pidge farm in Pawtucket, as well as the Babcock and Foster homes in the Hopkinton area. Locations that also have some claim as stations for fugitive slaves include the First Baptist and the Pond Street churches in Providence, and the Touro Synagogue and the George Downing house in Newport as well as houses in Mooresfield section of South Kingstown and Slate Hill area of Middletown Doubtless there are other places now unknown that were involved in the underground railroad.

Personal accounts or reminiscences of Rhode Islanders involved in the underground railroad are few. As noted, the most visible person involved in such activity was Elizabeth Buffum Chace. Often regarded as “the conscience of Rhode Island,” she left a printed account of her doings in a small book, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, published in 1891 when she was eighty-five years old and just several years before her passing. The following is an excerpt from her account:

From the time of the arrival of James Curry at Fall River, and his departure for Canada, in 1839, that town became an important station, on the so-called underground railroad. Slaves in Virginia would secure passage, either secretly or with consent of the Captains, in small trading vessels, at Norfolk or Portsmouth, and thus be brought into some part of New England, where their fate depended on the circumstances into which they happened to fall. A few, landing in some town on Cape Cod, would reach New Bedford, and thence be sent by an abolitionist there to Fall River, to be sheltered by Nathaniel B. Borden and his wife, who was my sister Sarah, and sent by them to Valley Falls, in the darkness of night, and in a closed carriage, with Robert Adams, a most faithful friend, as their conductor. Here, we received them, and, after preparing them for the journey, my husband would accompany them a short distance, on the Providence and Worcester railroad, acquaint the conductor with the facts, enlist his interest in their behalf, and then leave them in his care, to be transferred at Worcester, to the Vermont road, from which, by a previous general arrangement, they were received by a Unitarian clergyman named Young, and sent by him to Canada, where they uniformly arrived safely. I used to give them an envelope, directed to us, was sufficient by its post-mark, to announce their safe arrival, beyond the baleful influence of the Stars and Stripes, and the anti-protection of the fugitive slave law.

One evening, in answer to the summons at our door, we were met by Mr. Adams and a person, apparently in a woman’s Quaker costume, whose face was concealed by a thick veil. The person, however, proved to be a large, noble-looking colored man, whose story was soon told. He had escaped from Virginia, bringing away with him a wife and child. Reaching New Bedford, he had found employment, which he had quietly pursued, for eleven months. Being a very valuable piece of property (I think he was a blacksmith), his master had spared no pains in discovering his whereabouts; and, finally, traced him to New Bedford. Coming to Boston, he secured the service of a constable, and repaired to New Bedford, and went prowling round in search of his victim. But the colored people of that town, discovered their purpose, communicated with some of the few abolitionists, and the man was hurried off to Fall River, before the man-stealers had time to find him; and the Friends there, dressed him in a Quaker bonnet, and shawl, and sent him off in the daylight, not daring to keep him till night, lest his master should follow immediately. He said he carried a revolver in his pocket, and if his master should overtake him on the road, he would defend himself to the death of one of them, for no slave, would he ever be again. We sent him off on an early morning train, with fear and trembling; but, had the happiness in a few days, to hear of his safe arrival, of his having procured work, at once; and, afterwards, that he had been joined by wife and child. His master, after searching for him a whole day, in New Bedford, had returned to Boston, very much disgusted with the indifference of the “Yankee Mudsills” (as the lordly Southerners used to call New Englanders) to the misfortune of the slave-holders; and wrote an indignant letter to a Boston proslavery newspaper, in which he complained bitterly of their want of sympathy and co-operation, in his endeavor to recover his property. He said that, when he arrived in New Bedford, the bells were rung, to announce his coming, and warn his slave, thus aiding in his escape; and that every way, he was badly treated. The truth was, as we afterward learned, that he arrived at nine o’clock in the morning, just as the school-bells were ringing; and he understood this as a personal indignity.

The Chace book provides a fascinating account of other fugitives who came to her home. As these accounts are lengthy and too long to be quoted here the reader is encouraged to visit https://archive.org/details/antislaveryremin00chac and read them online. In one instance, Chace notes, the fugitive, a young black man who was harbored in her home for ten days, turned out to be a fugitive of a different sort—an escaped burglar from the New York State prison in Auburn.

In addition to specific accounts of slaves, Chace often mentioned Robert Adams. Adams, born in Scotland in 1816, had by 1826 relocated his family to Pawtucket where he went to work in a cotton mill owned by Samuel Slater. His obituary published in the Pawtucket Times on April 4, 1900 noted, “It was part of Mr. Adams’s work to convey from New Bedford to Pawtucket such as were stowed away and brought from the South in ships. All of this was done under cover. Quakers received Mr. Adams at Pawtucket and sent the refugees along another day’s journey toward safety.” [4]

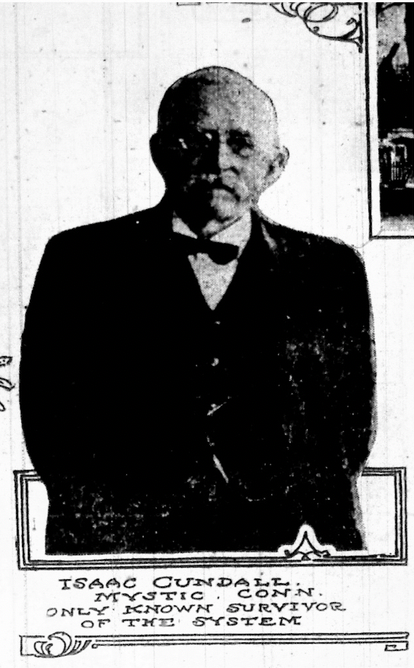

Another account provided by Isaac Cundall (1841 – 1929), published in 1918 in the Providence Journal, also provides a window into the workings of the underground railroad. [5] At the time of his first involvement in the underground railroad, Cundall was just sixteen years-old and living at his parent’s home in Ashaway. Cundall recalled the following:

One evening, in December 1857, when I was at my brother’s house, there came a knock at the door. Answering this, I was told that Uncle Jacob [Babcock] wanted to see me outside.

Uncle Jacob drew me quite a way apart from the house and when he had done this he said in an undertone, “I have a colored man slave I want you to take away to-night.”

I told him that I would have to see father about the business. I was but 16 years old then and naturally I wanted to consult with father before undertaking the mission. I knew all about the business and realized what was expected of me. There had been several slaves taken over our part of the “underground” except in the briefest possible way I had a full understanding of it.

Ours was the first “station” in Rhode Island. Where the slaves came from to us I never knew, and I never asked. Strict secrecy was observed; what we did not know we could not be expected to tell should anybody begin asking questions. All that I knew concerning the system was that ours was the first “station” and that the next one was at Mr. Foster’s house in Hopkinton.

Uncle Jacob said that I could do as I pleased with regard to his request, and that perhaps after all it would be better if I went home and talked with my father.

To my surprise, father was prepared for my coming, for as soon as I entered the house, he asked me if I had seen Uncle Jacob. If so, what did I propose to do? I replied that I did not know, but that it was up to him to decide. My mother, overhearing our conversation, asked what it was all about. “Don’t ask so many questions wife. Don’t be too inquisitive,” father replied.

My mother guessed right off I had been asked to pilot a negro over the road and asked me if I was afraid to engage in that undertaking.

This seemed to put me right on my mettle, for I replied that I was not afraid to do anything that was right. Looking into my father’s eyes I said, “Father, I will go.”

It was very evident that this was exactly the decision my father had hoped I would arrive at, for taking me by the hand he told me to go up-stairs and get into bed as though I was retiring for the night. There was ample reason for this strategy, for my brother-in-law was in the house. He was a strong pro-slavery man and had said that he would inform the authorities if he ever discovered the whereabouts of a fugitive slave.

Following father’s instructions, I went to bed and made the fact as clearly known as possible. About 11:30 o’clock I arose, dressed quietly, took my boots in my hand and crept down stairs. Father was asleep and waiting for me in the dining room. He had previously said “Isaac, you know what this means? If you are caught it will mean a fine of $1000 and six months in jail. Uncle Jacob and I will look out that the fine is paid, but you will have to take care of the jail end of the business. Only, my son, don’t tell who is to pay the fine, for if you should do that it will mean further trouble for Uncle Jacob and me.”

Father cautioned me to keep as quite as possible in hitching up the horse, and when the coast was clear I drove out of the yard and over to Uncle Jacob’s. Mr. Babcock was on the watch for me, so that there was no delay in getting the negro out of the house and up to the wagon. When the man saw me, he turned to Uncle Jacob and asked if he was to be sent away in the charge of a mere boy. Being assured that I would be all right, the man got in and we drove toward Hopkinton.

As we were nearing Well’s bridge, I heard another horse and wagon coming up the road after us. I realized that we were being hunted for and at my request the negro leaped over the side of the wagon and hid in the bushes by the roadside.

Something had to be done quickly on my part and springing to the horse’s head, I lifted one of the animal’s forelegs and began pounding on his shoe with a big stone.

While I was thus engaged the other rig came up and the driver halted his horse. To my surprise it was the sheriff of the county. He asked me what I was doing and where I was going. I told him my horse had gone lame because of the lodgment of a stone in its shoe and that when I got the stone out, I was intending to go for a doctor.

That was a most plausible excuse to offer, for the sheriff knew that there was no physician in our part of the country and that I would have to drive either to Westerly or Hopkinton to find one. He asked me if I had seen any other rig on the road. I told him I had not, which was absolutely true. Then he wanted to know if he could be of any assistance. I told him that I needed no help, and with this he whipped up his horse and drove on.

Waiting for the sheriff to get a good start I called to the negro to jump in again and soon we were at Mr. Foster’s place. I told Mr. Foster that I had a man for him and was told to bring the poor fellow in, but when I went back to the wagon the negro was not there. I called to him. Inducing him to come from behind the wall where he had hidden himself, fearing as he explained that I had made a mistake and taken him to the wrong house.

Mr. Foster led the man into the house and that was the last I saw of him although some time later we received word that the fugitive had been safely taken through to Canada.

I saw but one woman slave carried over our route, and I had the fortune to be selected as her guide, in March 1858. This time word was brought to me that Uncle Jacob had a woman who must be taken from the house right away even though it was broad daylight, as Sheriff Berry of Westerly, accompanied by the owner of the woman, was in our part of the town looking for the runaway.

On my way to Uncle Jacob’s house, I met the sheriff and the slave-owner, a Virginian. They showed me a large handbill, bearing a description of the woman, and offering a reward of $500 to whoever disclosed her whereabouts. “Here is a chance for you to make $500, my lad. Where is the woman?” exclaimed Mr. Berry.

I told him that I could not tell him that which I did not know. With this they drove on.

Upon my arrival at Uncle Jacob’s house, Mr. Babcock told me that it would be impossible for him to get the woman that night, as the sheriff was watching the roads too closely. “Isaac,” he said, “you must get her away from here now; as soon as possible. The sheriff will get a search warrant and look through all the houses hereabouts.”

I asked Uncle Jacob if his daughter, Sarah, was in the house, and, ascertaining that fact, invited her to take a ride with me. I think she must have divined my purpose, for she readily accepted. At my suggestion, she put on an old bonnet, pulled a heavy vail down over her face, and wrapped a big shawl about her shoulders.

We drove down the road, met Sheriff Berry, stopped and talked with him, and made it perfectly apparent that it was Miss Babcock who was with me. Sheriff Berry remarked that the weather was very cold, and I agreed with him on that point. We drove up the road for a mile, turned about, and purposely met the sheriff, telling him that it was so cold that we were obliged to go back for additional wraps.

Arriving at Uncle Jacob’s, Sarah took off the old dress, shawl and bonnet, directed the slave to put them on and gave her another outside wrap to throw over her shoulder. We made another start this time the heavily veiled slave being on the seat beside me.

Up the road we met Sheriff Berry. He seemed to persist in watching that part of the highway. As we reached him, I held up a trifle and exclaimed, “Now we are off.” “Good luck to you,” the sheriff shouted as we drove on.

I carried her to Preacher John Wilbour’s house, a short distance beyond Hopkinton and that night as I was told she was taken on to the next station. I never experienced any fear in thus piloting slaves. I was a boy, and the excitement of the undertaking appealed to me strongly. Other runaway slaves came that way in the years that intervened before the breaking out of the Civil War. My father died in 1861 and in the following year I entered the service remaining until after Lee’s surrender and the war had been brought to an end. [6]

Figure 3 is an image of Isaac Cundall taken at the time of his reminiscence in 1918, while Figure 4 is a photograph of the Jacob Babcock house as it looks today. The Cundall home is also still standing and is located on the corner of Main and West streets in Ashaway.

Unfortunately, few accounts of the underground railroad in Rhode Island exist. If it is discussed at all, Rhode Island’s role in the underground gets grouped in with other states. Even Rhode Island history books pay little attention to this topic with at best a paragraph or two vaguely touching on it. Interestingly, one of the best accounts of Rhode Island’s role in the underground railroad can be found in Horatio Strother’s book, The Underground Railroad in Connecticut, published more than a half century ago. For the few surviving homes on the underground railroad none have an historical marker commemorating its role in this important chapter in American history. To remedy this sad state of historical indifference the Rhode Island Heritage Harbor Foundation is undertaking an initiative to supply historical markers and interpretive signage to selected homes as part of its Historical Marker Initiative.

[Banner image: “Uncle” Jacob Babcock house, High Street, Ashaway. Babcock was a participant in the Underground Railroad (Russell DeSimone)]

Notes:

[1] Moses Brown managed a station at his residence at Humbolt and Wayland avenues. He also harbored escaped slaves on his farm lands, hid runaways on his fleet of merchant vessels, and provided funds for fugitives to pay for passage along their escape routes. [2] Charles Perry of Westerly harbored fugitive slaves at his house on Margin Street, often moving them to their next stop on the underground at his brother Harvey’s home in North Stonington, Connecticut. Perry also had constructed on his land in a wooded area near Shumuncanoc a number of stone cottages with sod roofs where fugitive slaves could stay until agents could convey them to their next stop. As such this hideaway as much as any house served as a station on the underground railroad. Following the 1857 Dred Scott decision, a number of terrorized free Rhode Island blacks, who had long resided in the state, took to living in these huts. [3] Jethro and Anne Mitchell were Middletown Quakers. Jethro, a vice president of the Rhode Island State Anti-Slavery Society, was brother to Daniel Mitchell of Providence [4] One known Pawtucket station along the underground railroad was the Pidge farm; it is conceivable Robert Adams conveyed fugitive slaves there as well as the home of Elizabeth and Samuel Chace in Valley Falls. [5} Cundall had previously presented a paper on the underground railroad to the Westerly Historical Society on October 11, 1917. [6] On August 7, 1862 Cundall enlisted in Company A of the 7th Rhode Island Volunteers and served until he was mustered out of service on June 9, 1865. Later in life he relocated to Mystic Connecticut and died there in 1929. He is buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Stonington, Connecticut.Bibliography:

Bartlett, Irving H. From Slave to Citizen. The Urban League of Greater Providence, 1854.

Best, Mary A. The Town That Saved a State. The Utter Co., 1943.

Blight, David. Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory. Smithsonian Press, 2001.

Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan. Amistad, 2005.

Chace, Elizabeth B., Anti-Slavery Reminiscences. E.L. Freeman, 1891.

Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom. W.W. Norton, 2016.

Hudson, J. Blaine. Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad. McFarland and Company, 2006.

Kuns, Richard and John Sabino (ed.). The Underground Railroad in New England. American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, 1976.

Mayer, Henry. All on Fire. St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Siebert, Wilbur H. The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom. The Macmillan Company, 1898.

Snodgrass, Mary E. The Underground Railroad – An Encyclopedia of People, Places and Operations. M.E. Sharpe, 2008.

Stevens, Elizabeth C. Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman. McFarland and Company, 2003.

Strother, Horatio T. The Underground Railroad in Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 1962.

Van Brockhoven, Deborah B. The Devotion of These Women – Rhode Island and the Anti-Slavery Network. University of Massachusetts Press, 2002.