Newport Gardner was born Occramer Marycoo, perhaps in Ghana, in 1746. When he was fourteen, he was captured and taken as a slave to Newport, Rhode Island, where he was sold to Caleb Gardner, a young Newport ship captain and later a merchant. Caleb Gardner changed his slave’s name to Newport Gardner. Newport, Rhode Island, was, as is well known, one of the premier ports in the thirteen colonies for slave trading (although most of the slave-trading was done by English merchants).

Considering the times, the Gardner family showed considerable benevolence toward the precocious boy, Newport Gardiner, making sure that he was educated at least as thoroughly as their own children. Within four years of his arrival in Newport, he learned English, French, and the basics of music, and became a Christian. (Of course, he had no knowledge of these languages or subjects before his arrival in Newport.) It is thought that he was taught music by composer Josiah Flagg and possibly by composer William Sampson Morgan, both who spent time in Newport in this era.

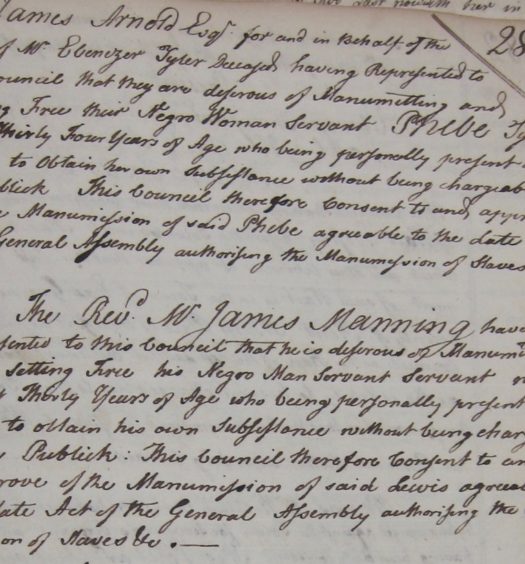

On the verge of the American Revolution on June 10, 1774, as a result of efforts by signer of the Declaration of Independence, Stephen Hopkins, the Reverend Samuel Hopkins (no relation) the pastor of Newport’s First Congregationalist Church on Mill Street, and wealthy Quaker merchant Moses Brown of Providence, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a law outlawing the importation of slaves to the colony, the first place in the New World to do that. However, the General Assembly felt that it had no authority over the behavior of Rhode Island residents when they were outside the colony, and thus Rhode Island merchants, such as the De Wolfe family of Bristol, were among the major importers of African slaves to Santo Domingo, Cuba, and other colonies in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century.

Rhode Island did not ban slavery until 1784, and even then the law did not apply to those who were already slaves in the state. Thus, the new law did not help Newport Gardner. Newport did marry a woman named Limas and they had five children. Probably a few were born before 1784 and a few after, so that some of his children were, like him, not covered by the law, and some were. Even the ones who were had to stay with their white masters until they attained adulthood.

House at 25 Pope Street in Newport, originally constructed around 1810 but greatly altered; believed to have been owned and occupied by Newport Gardner

The year 1791, when he was forty-five years old, was a special one for Newport. It is reported that in that year Gardner had the good fortune to be in a pool of friends who won the lottery, which enabled him to buy freedom for himself and his family. He then moved into a house on Pope Street and supported his family by teaching music. His former master’s wife reportedly was one of his students in music, dance, and composition. He was also a composer of music. After his freedom, he opened a school on School Street (the eighteenth-century building still stands) primarily to educate blacks.

In 1997, music historian Eileen Southern identified a tune, “Crooked Shanks,” as having been written by Gardner (before her death in 2002, she was not so sure).* The tune was published in 1803 in A Number of Original Airs, Duettos and Trios. Kate Van Winkle Keller’s National Tune Index makes it possible to find that this tune had been previously published for two English country dances: a 40-bar version for “The Seaside” in Bride, 1768 (published when Gardner was only 22 years old), and a 28-bar version for “Bill of Rights” in Thompson in the 1770s. I still believe that Gardner wrote both tune and dance directions, but I can’t prove it. Both dances were published in my 1990 book Country Dances of Colonial America, now out of print, but used editions are available online. (Incidentally, African-British writer-composer Ignatius Sancho, who was the first black to vote in a British election, published a collection of his English country dances in London a few years after Gardner in 1779. English country dancing was the most popular form of recreation for all social classes in the Europeanized world in the eighteenth century.)

All other music written by Gardner is presumed lost, including the musical part of a church anthem “Promise,” whose text survives, based on Jeremiah 30: 1-3, and Mark 7: 27-8.

Gardner was ordained a deacon in the First Congregationalist Church on Mill Street (the 1729 building still mostly stands, although now converted to condos). The pastor of this church was Samuel Hopkins, one of the nation’s leading ministers of his time and one of the first abolitionists outside the Quaker sect. Believing that the white establishment did not do enough to end the slave trade and slavery, and frustrated by continuing prejudice against blacks, Hopkins spent years trying, unsuccessfully, to organize a mission of free blacks to settle in Africa. Newport became a believer in the colonization movement and an admirer of Hopkins. In 1799, one of Hopkins’s last years as a preacher, Newport, then a sexton of the First Congregational Church, would walk or ride with Hopkins every Sunday in a one-horse chaise to the meeting house and help the elderly pastor to mount the steps to his pulpit. Newport would then sit behind the infirm preacher, ready to assist him if needed. Hopkins died in 1803.

Eventually, the black members decided to separate and founded their own Colored Union Church in 1824 (whose later gothic-revival building still stands on Division Street, now used as a residence), and Gardner transferred his membership along with them.

A good indication of how educated one was at this time was to read his or her letters. Newport’s letters, in beautiful handwriting, showed that he had excellent English writing skills, much better than most whites of the period. In 2012, with donations from its members, the Newport Historical Society purchased an 1821 letter Gardner wrote his niece Sarah Burk in Alexandria, Virginia. He wrote, “I received yours dated June 25 with great pleasure; for as cold water to a thirsted soul so is a good news from far country: I rejoice to hear that there are two coloured churches there, and that one of these have two hundred communicants; I hope they are not only professor, but professor of true religion.”

During the American Revolution, British troops and officials set free thousands of slaves they encountered in America, including a few in Newport. At war’s end, many ex-slaves were crowded in British-held New York City, until they were transported by British vessels to Halifax and other Canadian ports. At the end of the war, these former slaves in Canada began to petition the British government for a place in Africa to which they could return, and so in 1786 the British bought the colony of Sierra Leone for them, and the first British blacks arrived there on May 17, 1787; they called their first settlement Freetown.

By 1820, a similar movement arose in the United States, backed in part by the Reverend Samuel Hopkins until his death in 1803. After being pressed with petitions from white and black Americans, slave-holding President James Monroe acquired a piece of Africa near Sierra Leone where blacks could voluntarily go. The new colony was named Liberia (Land of Liberty) and was named in honor of the President, Monrovia. Many blacks in the United States then emigrated to Liberia, but they faced two hurdles. First, they had no immunities to African diseases, so they died with alarming frequency. Second, the indigenous blacks resented the arrival of the American newcomers, so that they started a civil war that continued at varying intensities until just a few years ago.

Newport Gardner thoroughly backed the Liberia project and proselytized for it. Leading a group of about thirty African American colonists, in late December 1825, he departed for Liberia. But, tragically, he died of disease only a few months after arriving.

Still, the extraordinary Newport Gardner is the first black musician to be identified as a professional music teacher and composer.

*Professor Eileen Southern, author of The Music of Black Americans, told me that, since Gardner was a Congregationalist deacon, he would never have written a dance tune because dance was anathema to Congregationalists. This is not true. First of all, he was not a deacon at the time that he wrote the tune. Second, even though Congregationalists were banned from participating in Morris and maypole dancing, which were deemed to be associated with too much licentious behavior, English country dance (in the sixteenth century, but not so much in the eighteenth century, closely related to Morris and maypole dancing) was central to their lives. Whenever possible, for example, a Congregationalist minister would sponsor an English country dance ball not only to celebrate his ordination, but also even his installation at a new church.

[Banner image: Current view of the First Congregational Church in Newport, whose pastor was the Reverend Samuel Hopkins, and at which Newport Gardner attended]For further reading:

Joseph A. Conforti: Samuel Hopkins & the New Divinity Movement (Christian University Press, 1981)

John Fitzhugh Millar: Country Dances of Colonial America (Thirteen Colonies Press, 1992)

Eileen Southern: The Music of Black Americans: A History, 3rd ed. (W. W. Norton & Co., 1997)

“Newport Gardner Letter,” Newport Historical Society website, in History Bytes, at http://www.newporthistory.org/2012/newport-gardner-letter/