Newport never fully recovered as a thriving maritime port following the American Revolutionary War. Its merchants did well in the trade with India and China in the times around 1800. Then whaling helped. At one point, Newport had a whaling fleet of a dozen or so ships. But whaling did not provide the cure for long; by 1849, the whale fishery in Newport was on the decline. When Newport mariners heard about the California gold rush in late 1848, they caught “gold fever” and found the urge to try their hands at mining gold irresistible. At the time, California had few settlers from the United States and little was known about it in the East.

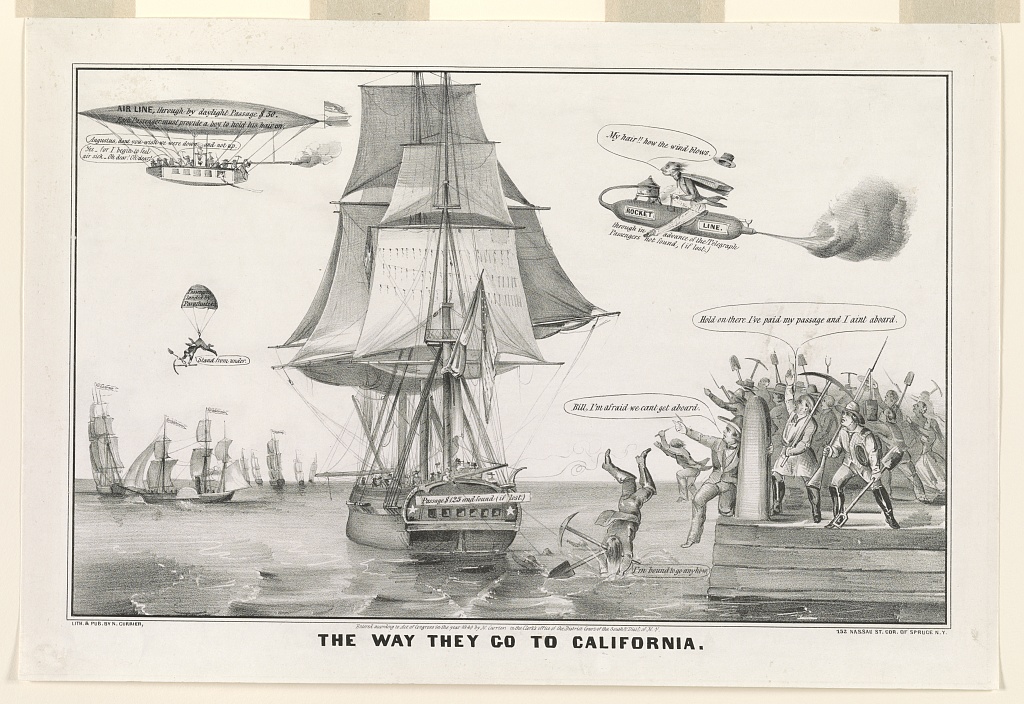

“The Way to Go to California.” The New York authors poke fun at the rush to sail to the California gold mining fields, circa 1849. The rocket and balloon at remarkable! (Library of Congress)

Newspaper reports in December 1848 covered President James K. Polk’s address to Congress in which he announced the discovery of gold in California. But Newporters may have found about it eve earlier. Reportedly, Newporters were inspired to form a company to sail to San Francisco by news of the gold finds brought to Newport by Charles Stanhope. He had sailed into San Francisco just as gold was discovered in California in 1848. At the time, Stanhope was serving as an officer aboard a whaling ship commanded by Captain Sherman of Newport.

Writing in an article for the Newport Mercury in 1882, Charles Stanhope of Newport recalled that the “gold fever” in the winter of 1848 and 1849 had resulted in several New England seaports sending out expeditions of fortune hunters to California before the fever reached Rhode Island. He further recalled that gold fever:

was the all-absorbing topic of conversation in our streets, back shops, in fact everywhere. The late Capt. Charles Cozzens, James R. Newton and the writer were one evening conversing upon the subject, when one of the number proposed something like this, “I believe a company could be raised in Newport to buy and fit out a vessel for an expedition; suppose we try the experiment.” The proposition was agreed to and a notice calling for a meeting was inserted in the newspapers for conference upon the subject. The meeting was held in the sail-loft, on Devens’ (now Commercial) wharf, occupied by the late Benjamin Freeborn, which was largely attended, and great enthusiasm prevailed. The meeting was organized by the election of a president, secretary and treasurer. Several meetings were held and action was taken, and in the Newport Mercury of January 6, 1849, the following notice appeared: “Ho for the Land of Gold. We understand the whaling ship Audley Clarke has been purchased by a company in this town for an expedition to California.”

William A. Coggeshall of Newport was selected as the President of the venture. The Audley Clarke was repaired and refitted and provisions were purchased for a long voyage to San Francisco. The passengers and crew included some of the top maritime families of Newport.

The Audley Clarke was built in Newport in 1833 by William H. Crandall and Son, which had a shipyard on the Point. Audley Clarke of Newport, for whom the ship was named, was the vessel’s main investor. The ship weighed 333 tons. Its original use was as a whaling ship.

The Rhode Island Republican, a Newport newspaper, occasionally carried snippets of information about the vessel’s far-flung whaling voyages. For example, in March 1836, it was reported that Peleg Burroughs, a chief’s mate from the ship, had been dragged off a small whaleboat and killed after getting caught in the rope that was attached to a harpoon embedded in a fleeing sperm whale. In February 1839, the Audley Clarke of Newport was reported being seen in the Pacific Ocean with 800 barrels of sperm oil on board, nine months out of Newport. In its August 12, 1840 edition, the Audley Clarke was reported to have returned to Newport a week earlier with a full load of 2,350 barrels of sperm oil. Its owners were P. and A. Clarke, R. Coggeshall, and others. In a November 1847 edition of the newspaper, it was reported that the captain of the Audley Clarke had committed suicide in Hawaii. The next month, it was reported that the whaling vessel, with just 600 barrels of sperm oil as of April 1847, was on its way to Japan. After a three year voyage, the ship returned to Newport in 1848.

The Audley Clarke departed Newport for San Francisco on February 15, 1849, at around 2 p.m. Despite the frigid temperatures, many Newporters lined the Point District to see the ship and its passengers off. On board were 70 passengers and crew, and two stewards and two cooks. A total of 56 of the passengers and crew hailed from Newport, five from Providence, five from Bristol, two from South Kingstown and two from Massasoit also joined the voyage.

All of the people on board the Audley Clarke were men. They must have thought that the remote gold fields of the interior of California were no place for women or children. Losing so many Newport sailors accelerated the decline of Newport as a whaling port and must have been a blow to the town’s maritime industry.

On its first day of sailing, the Audley Clarke was found to have three feet of water in its holds, but the eager passengers and crew carried on, taking shifts pumping out the water. March 21st was the first day of good weather, at 82 degrees, but the ship continued to leak forcing thirty men to continue to man the pumps. On the 39th day of the voyage, the ship landed at St. Antonio, one of the Cape de Verde Islands, where more provisions were purchased and the leak was plugged.

On May 31, the Audley Clarke was sailing between the Falkland Islands off Argentina in South America and Cape Horn, when the passengers and crew experienced their first “heavy” gale. On June 9, the ship passed the longitude of Cape Horn 100 miles south of land. Another gale struck the ship, lasting some thirty hours. The Audley Clarke eventually safely reached the Pacific Ocean. The ship proceeded in decent weather up the west coast of South and North America.

The Audley Clarke finally sailed through the Golden Gate and arrived in San Francisco Harbor on September 1. It had been a relatively fast voyage of 198 days. The Magnatia, which had sailed from New Bedford a day before the Audley Clarke left Newport, had arrived at San Francisco a day before the Audley Clarke.

The passengers and crew members at once headed for the gold fields. They did not stick together. Some worked individually and others joined small companies.

The Audley Clarke was brought up the Sacramento River for a temporary stay. Some of the passengers and crew returned from the mining fields, took the ship back to San Francisco, and spent the rest of the winter on it. Later it was sold. The crew members had no intention of returning to Newport with it. They left for the gold fields too. This was a common approach at the time; indeed, many of the old whalers were simply abandoned by their crews. After housing miners and being used for a storehouse through the Civil War, the Audley Clarke was eventually sold for scrap iron and copper.

The fate of all the passengers and crew are not known. No one died on the voyage to San Francisco, but William Welsh passed away from unknown causes twenty days after landfall. A few may have died of disease in the unsanitary mining camps. Many likely did not succeed in gaining much wealth. Some got out of mining and did better establishing small businesses in San Francisco and other towns.

Eventually, many of the ‘49ers drifted back to the East. It may be that these returnees all along had the idea of getting rich and returning to Rhode Island with their new-found wealth. As maritime men, they did not find the prospect of another voyage around Cape Horn as daunting. They must have missed their families, and they likely did not appreciate the lack of women in California. Still, others saw opportunities in California to begin a new life and stayed there.

William W. Morris, Benjamin Malbone, William H. Gardner and Oliver Hazard served as stewards and cooks on the Audley Clarke. In the 1840 census, Morris was listed as a 40-year-old man of color residing in the seafaring island of Nantucket. He was still listed as residing in Nantucket in 1850, indicating that he returned there, Malbone was listed as 23 years old in February 1849. He may have been the son of Jeremiah Malbone, a man of color from Johnston, Rhode Island (Benjamin may have been the male minor listed in Jeremiah’s household in the 1840 census). Gardner and Hazard were minors—Hazard was listed as age fifteen in May 1848 and Gardner age fifteen in February 1849. Their race is not indicated in a listing of seamen, suggesting that they were white. Malbone and Gardner received their sailor’s certificates only five days before the Audley Clarke sailed from Newport, suggesting that they had little or no prior experience as sailors.

In 1886, the Newport Mercury reported that at least the following fifteen ‘49ers then resided in Newport: Levi Johnson, Michael Cottrell, Benjamin A. Sayer, Stephen R. Goffe, John Tompkins, William H. Fludder, Thomas Barlow, Joseph P. Barker, William E. Dennis, William T. Dennis, George B. Slocum, James M. K. Southwick, Joseph M. Lyon, William K. Lawton, and Benjamin Brown. Only John Y. McKenzie was noted as still residing California; he was in San Francisco. At one point, he owned and operated a small vessel in San Francisco Bay that ferried cargo from large ships to the wharves on land. By 1888, about half of the original ‘49ers were dead.

Here are excerpts from a letter, dated January 4, 1888, from one of the Audley Clarke passengers and crew, an unidentified man who then resided in San Francisco. He provides fascinating accounts of five others who remained in California.

Jack Caswell is up at California City, six miles from this city, where he is building a small schooner for a firm in this city to send north for a fishing cruise—he is the same old Jack. . . . James Demarest is well. He is with George Knowles & Son and looks old. George (alias Bazoa) Crandall is still alive and lives at Boston Ravine. He goes off on a prospecting tour and discovers some ledge and sells it and makes a living that way; he has sold some very good [gold] claims for a song, but he is happy and content. George Beatty is up at Georgetown; he is mining and has made some money. He has a family, I think two grown-up boys. Moses Lewis, alias any-chance-to-get-out, is living near Stockton. I have not heard from him for some time; he is a clerk on one of the small steamers that runs on the San Joaquin up to Hill’s Ferry when the river is high. This is all of the Audley company I know to be alive out here.

By 1907, some were still living in Newport or elsewhere on the east coast. James M. K. Southwick, for example, returned to Newport and established a successful business in the port town. George B. Slocum returned and served as a captain of steam ships running from New York City to Buenos Aires. William T. Dennis returned to Newport and opened a market he operated for many years called the Yuba Dan Market. His cousin William E. Dennis also returned to Newport, but then he departed back to California with his son. Benjamin Cozzens returned to Newport and ended up in the Soldiers Home in Bristol, and William Stevens, 3rd was in a Soldiers Home in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Hiram Harrington, formerly of Newport, had recently died at Fall River. Edson Stewart and Joseph W. Arnold were residing in Boston in 1893.

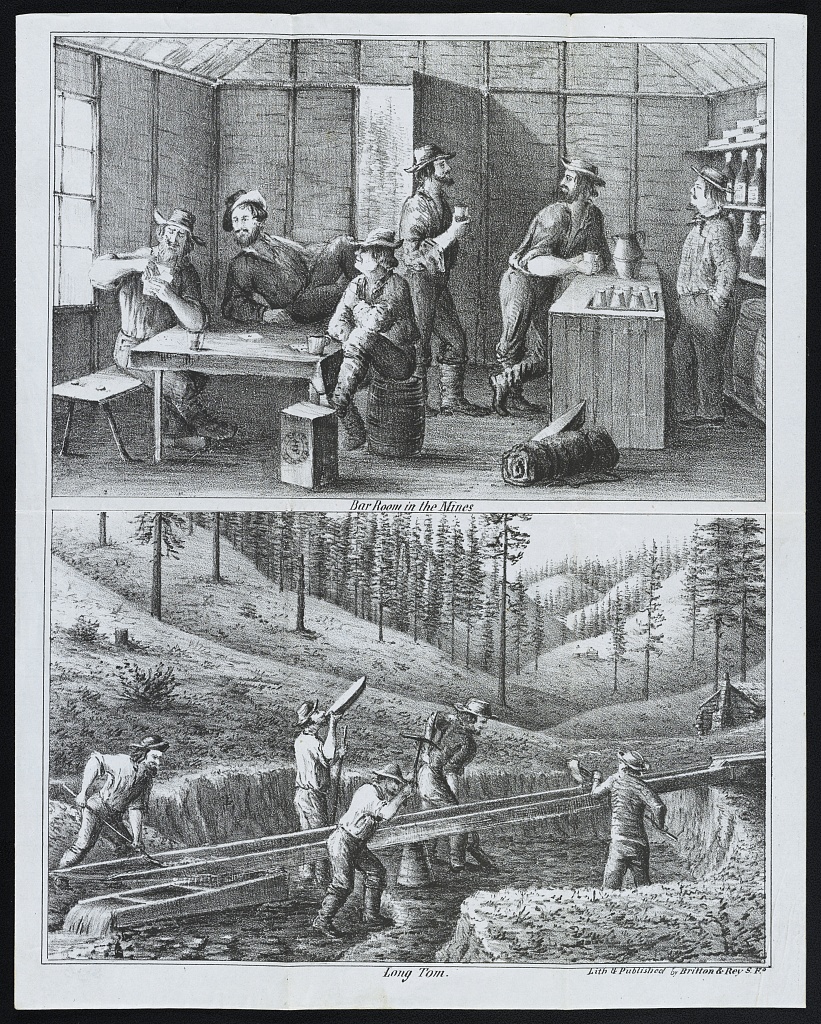

Gold mining scenes in California, including a bar room in the 1850s. Only men are shown. (Library of Congress)

In 1907, George Crandall and John C. Caswell were thought to still be alive in California. Others who never returned from California included George Beatty, Elisha P. Kenyon, John Y. McKenzie, and Moses A. Lewis (formerly of South Kingstown). George H. Tilley moved to and remained in Oregon. The venture’s president, William Coggeshall, died in San Francisco on May 7, 1882. It was reported that a few of the men travelled further on to Australia, presumably to continue the lives of miners, and died there. James M. K. Southwick of Newport was reportedly the last survivor of the crew of ‘49ers, dying in 1912.

The Audley Clarke was one of many ships from East Coast ports that carried prospective miners to California in 1849. For example, some 650 sailors on fourteen ships departed Nantucket for the gold fields of California.

On its voyage to San Francisco, the Audley Clarke crossed paths with the bark Velascu, 46 days out from Boston, Massachusetts. On board were 96 persons, many of them from Pawtucket and bound for San Francisco. The two ships entered a port on a small island together and the Rhode Islanders enjoyed each other’s company for a day.

Thanks to a 2008 article in the Union Times newspaper of Grass Valley, California, which relied in part on information provided by a descendant, some detailed information is known about one of the ‘49ers, George Crandall. George Henry Crandall was born in Newport on October 16, 1825, the eighth and youngest child of Joseph (1785-1848) and Martha (Cottrell) Crandall (1790-1847). Crandall was a well-known name in Rhode Island. Joseph Crandall was a seafarer, known as Captain Crandall, and had sailed the waters of the Atlantic for 54 years.

In 1848, hearing the reports about California, 24-year-old George caught gold fever. As an eighth child, his prospects for inheritance were limited. The whaling trade in Newport was in decline. He had to earn his own way in the world. Crandall signed up to sail on the Audley Clarke.

After landing in San Francisco, Crandall likely took a crowded steamer to Sacramento, bought supplies, and then headed for the gold fields in Grass Valley, a major mining town in western California in Nevada County near the Nevada border. The Union Times’s newspaper account places him at the site of the first discovery of gold-bearing quartz on Gold Hill in Grass Valley in September 1850.

In the book “History of Placer and Nevada Counties,” authors Lardner and Brock gave an account of a discovery in which Crandall was involved:

In September 1850, George McKnight, who was camped on the top of the hill, noticed some gold cropping near his tent; he dug down a few feet, to find gold in the quartz. Young George Crandel [Crandall]) rushed down to Boston Ravine with the news that the hill was “all gold.”

This and other discoveries allowed Crandall to leave the difficult life of a miner and build a hotel with $5,000 of his earnings in Boston Ravine. But in 1855, fire destroyed the building and an uninsured Crandall had to start all over again.

The Union Times newspaper article continues:

An early deed reveals that, in the 1850s, George was a principal in the partnership of Spencer, Crackling, Crandall & Company, owners of a 1,200-foot quartz claim on Gold Hill, while other deeds indicate he sold off several small claims described as part of the “Crandall Lode,” a 1,500-foot quartz claim in the same area.

George named Rhode Island Ravine in honor of his birthplace and built his home on Brighton Street at what is now the corner of Hocking Avenue [in the town on Grass Valley].

Crandall married a woman whose background was described in a census as “South American Spanish.” The couple had four children, but Crandall’s wife died relatively young in about 1870. Since Crandall was a miner by trade, and spent much time away from home, three young children were placed in a local orphanage, the Holy Angels Orphanage operated nearby by the Sisters of Mercy. There, Alice, Charles Henry and little Mary Louise grew up. The older George Crandall, Jr. resided with his father. They lived close enough to the three younger children that the family in some sense stayed close together.

Crandall continued to mine, but his children must have left Grass Valley when they could. In the 1888 letter quoted above in this article, the following was said about the old miner:

George (alias Bazoa) Crandall is still alive and lives at Boston Ravine. He goes off on a prospecting tour and discovers some ledge and sells it and makes a living that way; he has sold some very good [gold] claims for a song, but he is happy and content.

Crandall died at the age of 83 on July 20, 1908, in the County Hospital outside Nevada City. His death was noted on the front page of the July 22, 1908 edition of the Grass Valley Daily Union newspaper. The first sentence of the obituary concluded, “The deceased had an interesting and varied career, and kept to himself of late years, but was fondly attached to his old home in Rhode Island Ravine, where he lived so many years.” Crandall died as a pauper and no stone marked his grave.

A descendant of Crandall’s, studying family genealogy, turned up 97 descendants of George and his wife. Rhode Island Ravine outside Grass Valley retains its original name.

* * * *

Here is a list of the passengers and crew of the Audley Clarke, for the benefit of genealogical studies.

Company Officers: President, William A. Coggeshall. Aaron F. Dyer, Treasurer. George W. Langley, Secretary.

Company Directors: William A. Coggeshall, Charles Cozzens, George Vaughn, A. W. Dennis, Isiah Crocker, and James H. Demarest.

Ship’s Officers: Ayrault W. Dennis, captain. Charles Cozzens, first mate. George R. Slocum, second mate.

Stewards and Cooks: William W. Morris, Benjamin Malbone, William H. Gardiner and Oliver Hazard.

Passengers and Crew from Newport (including officers, directors and ship’s officers): Samuel Young; James M. K. Southwick; Freeman M. Hoxie; George H. Tilley; Joseph M. Lyon; George Beatey; William K. Lawton; Arnold Pearce; James H. Demarest; Oliver Carpenter; George Crandall; John H. Spooner; John C. Caswell; Benjamin A. Sayer; Stephen H. Goff; Thomas Cranston; George Vaughn; Isaiah Crocker; Charles Cozzens; Levi Johnson; Ayrault W. Dennis; William H. White; William T. Dennis; George W. Babcock; George H. Slocum; John Y. McKenzie; William Stevens, 3rd; Edwin Chambers; Weld Hatch; Aaron F. Dyer; Jacob Lake; Robert P. Clarke; George W. Langley; Frederick A. Murphy; John Tompkins; Joseph Southwick, Jr.; John S. Hudson; William Welch; Benjamin Cozzens; Irving H. Knowles; Charles R. Clark; William A. Coggeshall; George J. Stagg; Michael Cottrell; Joseph King; Samuel B. Friend; Benjamin Brown; William H. Fludder; Thomas Barlow; John H. Cox; Joseph N. Riggs; Joseph P. Barker; John Freeborn; William Weyeser; Hiram C. Harrington; and William E. Dennis.

Passengers and Crew from Bristol: Amos T. Whitford; Zachariah Chafee; Nathaniel F. Wardwell; Charles Phelps (spelling?).

Passengers and Crew from Providence: Cornelius E. Cummings; Joseph W. Arnold; George H. Wheaton; Robert Graham; and Jeremiah C. Bliss.

Passengers and Crew from Massasoit: Richard Barstow and Joseph M. Barstow. [The 1840 census shows a Rickart (or Richard) Barstow, and a son, residing in Rochester, Plymouth, Massachusetts]

Passengers and Crew from South Kingstown: Moses A. Lewis and Elisha P. Kenyon.

Sources:

The material for the Audley Clarke is all from editions of the Newport Mercury, which published retrospectives on the voyage of the ‘49ers on some of its anniversaries. See “The Audley Clarke’s Voyage, May 20, 1882, p.1; Untitled, Feb. 11, 1886, p. 4; “A Memorable Anniversary,” Feb. 20, 1886, p. 1; “Anniversary of Forty-Niners,” Feb. 16, 1907, p. 1; “The Audley Clarke,” Feb. 15, 1919, p. 8; “Seventy-Five Years Ago, Mercury Feb. 17, 1849,” Feb. 16, 1924, p. 8. See also “Some Eccentric Characters Who Sailed on Newport Vessels,” Newport Mercury, Aug. 2, 1918, p. 6.

A thorough analysis of the U.S. censuses would result in a more complete picture of where the ‘49ers resided at a particular point in time. It would make for an interesting project, to see how dispersed they were. Genealogical records and Civil War records could also be consulted.

For the squibs on the Audley Clarke on its whaling voyages, see Rhode-Island Republican, March 30, 1836, p. 3; Oct. 31, 1938, p. 3; Feb. 13, 1839, p. 3; March 6, 1839, p. 3; Aug. 12, 1840, p. 3; Nov. 6, 1847, p. 2; Dec. 2, 1847, p. 2.

For the stewards and cooks, in addition to the 1840 and 1850 federal censuses, see Registers of Seamen’s Protection Certificates, Mystic Seaport Museum, at www.research/mysticseaport.org (click on Digital Resources, Databases and then Seamen’s Protection Certificates).

For George Crandall, see “The Search for George Crandall,” July 15, 2008, The Union (Grass Valley, California) at https://www.theunion.com/news/local-news/the-search-for-george-crandall/article_0ef52fbd-bb87-5461-98fe-b120cf4704cb.html?utm_medium=social&utm_source=email&utm_campaign=user-share. Grass Valley, California, has a mining museum. If anyone reading this article ever visits it, please take some photos of it and the surrounding area and send them to me!