[Editor’s Note: I have started to try to determine when the last slave auction was held at Newport involving captives purchased from Africa and brought directly to Newport. In colonial times, Newport was by far the leading slave trading town in all of the thirteen American mainland colonies. But the great bulk of the captives were carried to British Caribbean islands and, to a lesser extent, South Carolina and Virginia. Few were brought directly to Rhode Island. The last slave auction in Newport by a slave ship returning from Africa I have been able to locate so far occurred in 1762. It was not successful. The investors in the voyage, Newport merchants William Vernon, Samuel Vernon, and Thomas Taylor, had to advertise the auction at Banister’s Wharf in four editions of the Newport Mercury, and even then not all of the captives on board were sold. The ship’s captain sailed to Philadelphia to sell the remaining captives.

In any event, the coming of the American Revolutionary War brought more opportunities for slave auctions. Privateers captured enemy vessels at sea and sometimes the “cargo” included enslaved people. For example, Esek Hopkins, when commander in chief of the Continental Navy, after capturing a small Royal Navy vessel in October 1775, offered up at auction in Providence seven Black men, whom he claimed had been enslaved by Newport Tories and were members of the captured ship’s crew. For more on the treatment of Black prisoners by American privateers, see Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Westholme, 2022), pages 44-45.

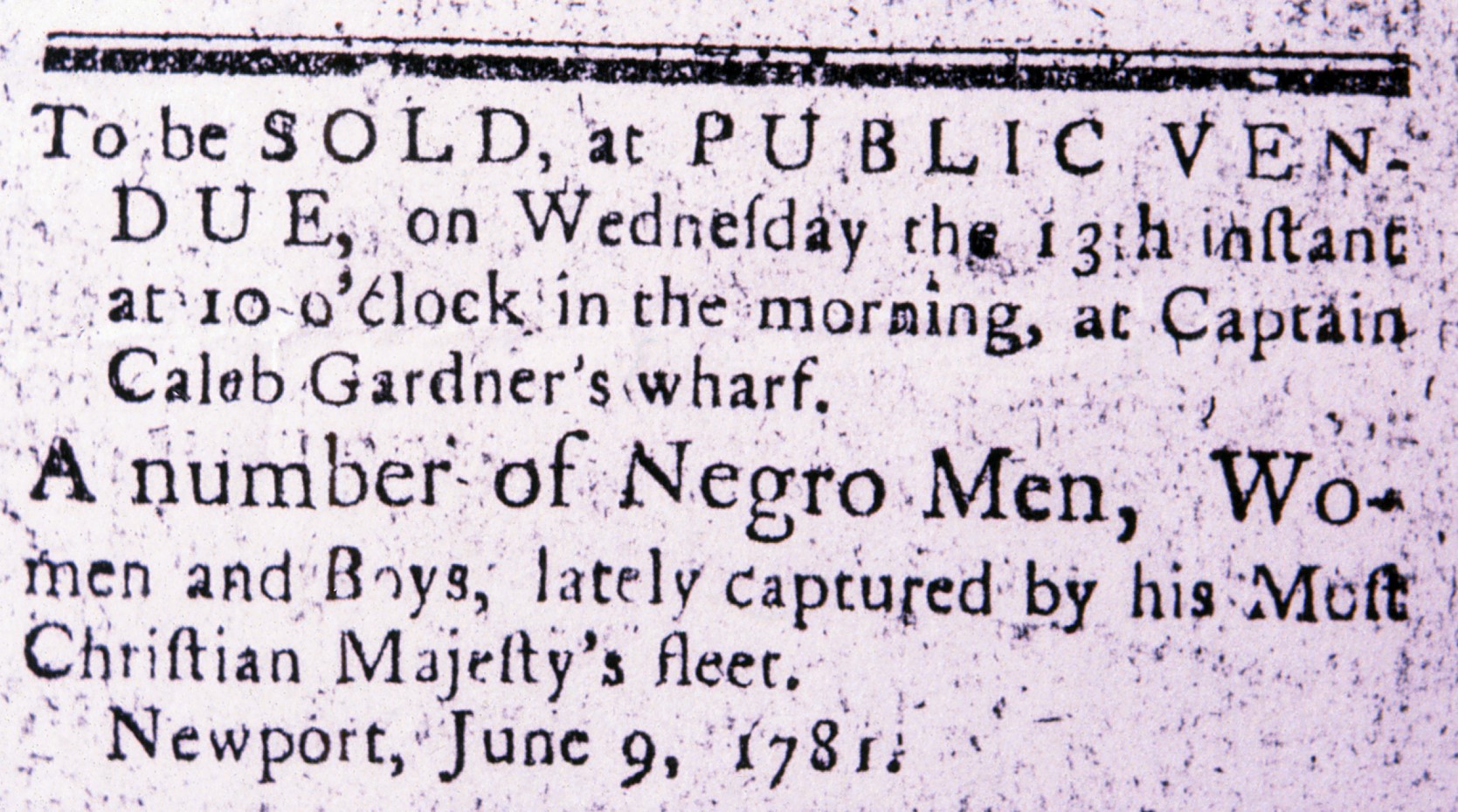

In this article, historian Robert Selig writes about what may be the last slave auction in Newport, which was held by the French forces occupying Newport in 1781. French forces had captured enslaved Blacks in a campaign in Virginia and had put them up for auction at Captain Caleb Gardner’s Wharf in Newport. (Gardner was an experienced slave ship captain himself.)

Robert Selig is perhaps the leading historian working on General comte de Rochambeau and the French allies who helped the Americans win independence from Great Britain. The article below is excerpted from a study of Rochambeau’s army in the State of Rhode Island. The name of the report is, Robert A. Selig, The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route in the State of Rhode Island, 1780-1783, An Architectural and Historical Site Survey and Resource Inventory, Project Sponsor: Rhode Island Rochambeau Historic Highway Commission, Project Director: Roseanna Gorham, Chairman, Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route – Rhode Island (W3R-RI) (2006, updated 2015). The portion of the entire study that includes the material in this article can be accessed at http://w3r-archive.org/history/library/seligreptri3a.pdf. This excerpt, with minor revisions, is from pages 226 to 230.]

Comte de Rochambeau and his fellow generals had eight, ten, or more servants, but many of them tried to acquire one of the most important status symbols of the eighteenth century: a black servant. One of Closen’s servants was a black man named Peter, “born of free parents in Connecticut,” who accompanied him to Europe in 1783. The last opportunity to acquire a black man – or woman – before the departure from Rhode Island came on 13 June 1781. On 9 June 1781, the Newport Mercury ran an advertisement that on Wednesday, 13 June, “at 10 o’clock in the morning, at Captain Caleb Gardner’s wharf, A number of Negro Men, Women and Boys, lately captured by his Most Christian Majesty’s fleet” would be sold to the highest bidder.

In what may have been a pre-public sale, Rochambeau on 5 June 1781 acquired an unnamed African-American slave “fait prisonnier lors de la prise de ‘La Molli’ – taken prisoner in the capture of the ‘Molli’” on 19 February 1781. The purchase price, 170 Spanish Silver dollars or about 900 livres, was a bit more then 1/3 of the 100 guineas or 2,450 livres the marquis de Laval had paid Wadsworth for a 10-year-old stallion in April 1781.[1] How did these slaves get to Newport?

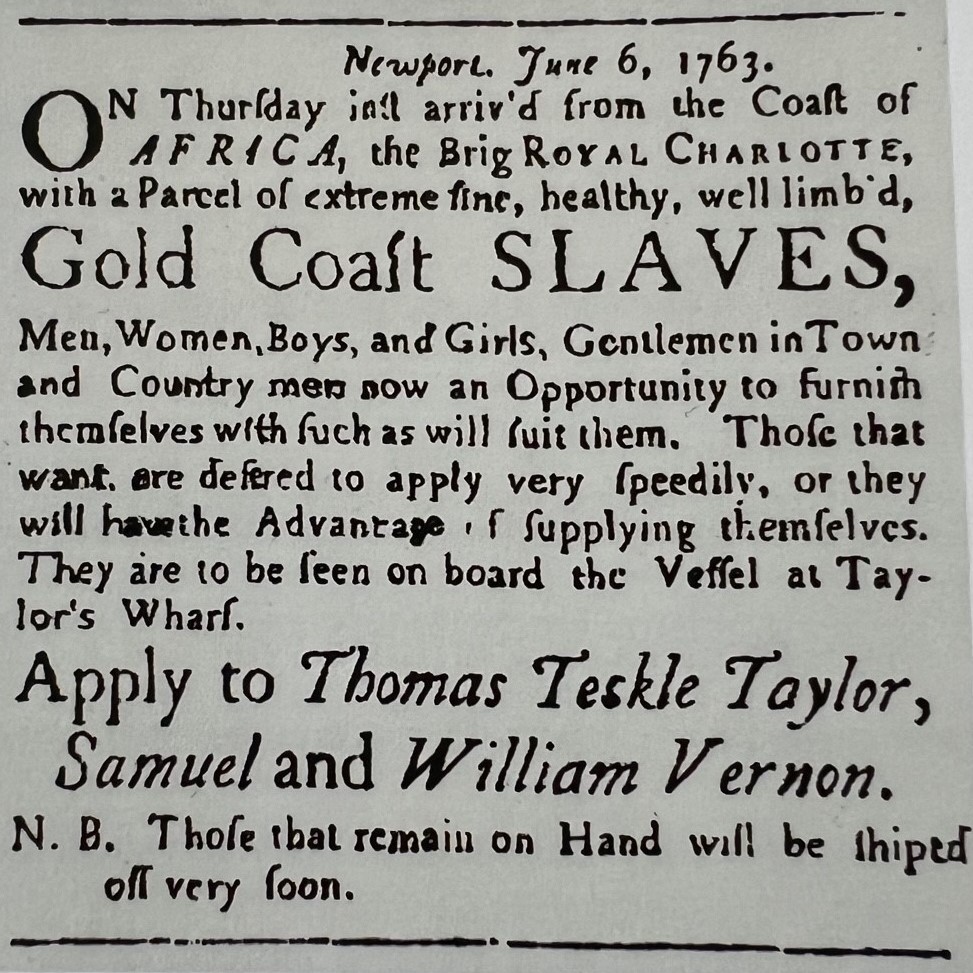

Newspaper advertisement for a slave auction to occur at a wharf in Newport sponsored by Newport merchants and slave traders William and Samuel Vernon, and their ship captain who sailed to Africa and back, Thomas Taylor. The advertisement appeared in the June 6 and June 13 editions of the Newport Mercury.

On 9 February 1781, Captain Le Gardeur de Tilly had sailed from Newport for Virginia on the 64-gun l’Eveillé accompanied by the frigates La Gentille and La Surveillante plus the cutter La Guêpe. His task was to assist in the capture of Benedict Arnold, who had disembarked with 1,200 men at Portsmouth on 31 December 1780, captured Richmond on 5 January 1781 and was wreaking havoc on the plantations along the James and York rivers. On 18 February 1781, Tilly’s small flotilla arrived off Cape Henry where it took the corsair Earl Cornwallis (16 guns and a 50-man crew), the Revenge (12 guns and a 20-man crew), a third corsair of 8 guns and a 25-man crew (possibly called Duke of York) as well as a sloop carrying a load of flour. On the 19th she chased and took the Romulus of 44 guns and a 260-man crew as well as a brick with 59 réfugies from Virginia. Many of the refugees were slaves who had run away from their owners in the hope of gaining their freedom upon reaching British lines. One of the 59 refugees captured on the brick, i.e. the “La Molli – the “Molly,” was Rochambeau’s slave.[2] Worrying about being trapped by a larger British fleet, Tilly decided to return to Rhode Island and sailed back into the harbor of Newport on 3 March.[3]

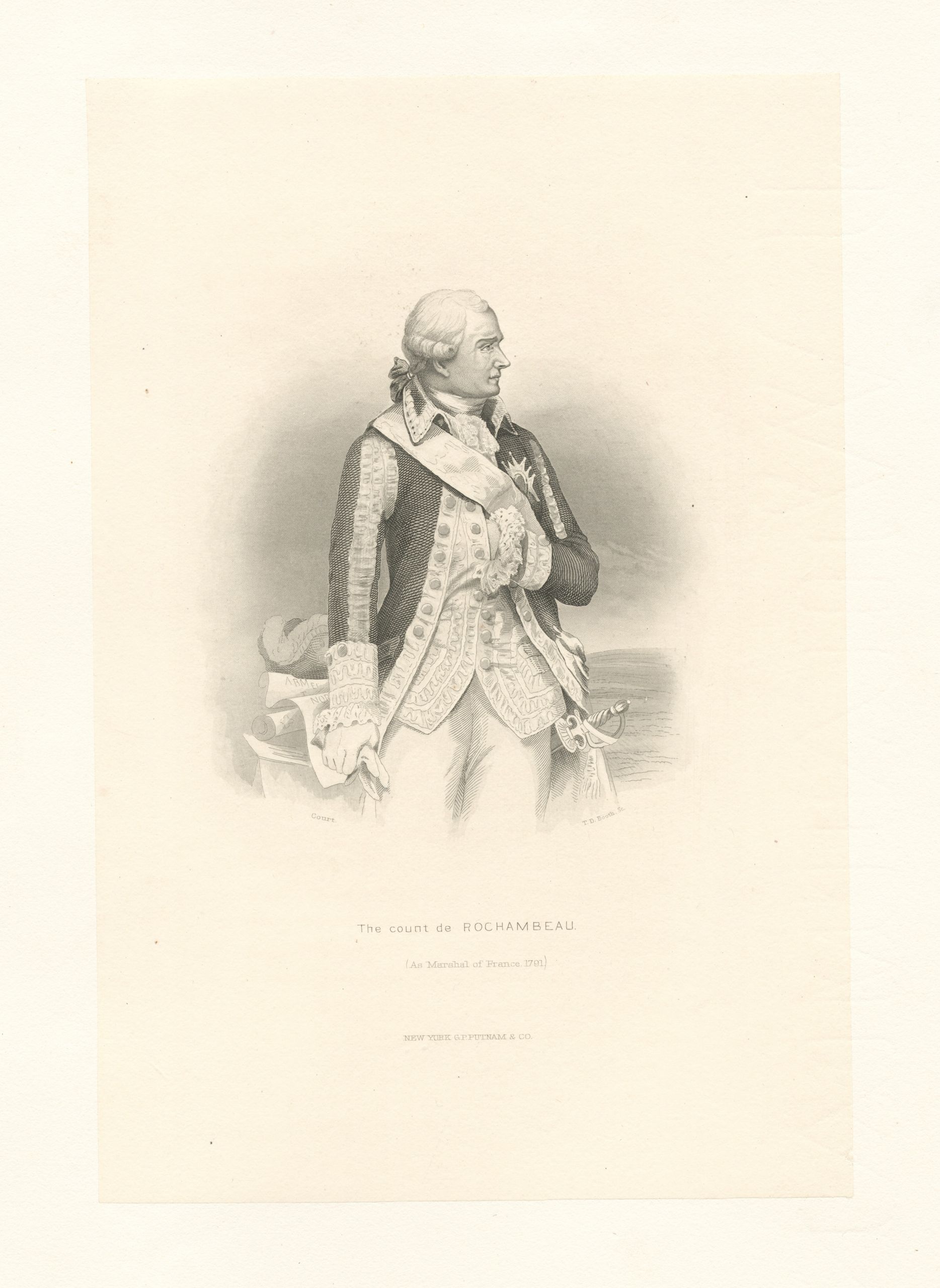

The Comte de Rochambeau commanded the French expeditionary force that arrived in Newport in July 1780 and departed in August 1781—for the joint French and American victory at Yorktown, Virginia (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

We do not know the slave’s whereabouts between his arrival on 3 March and the sale on 5 June, and he may, or may not, have been part and parcel of those identified as “lately captured by his Most Christian Majesty’s fleet” to be sold on 13 June. That fleet consisting of seven ships of the line and the recently captured frigate Romulus under Charles René Dominique Sochet, Chevalier Destouches (or Des Touches), again tasked with assisting in the capture of Benedict Arnold, had sailed from Newport on 8 March 1781, with all of Rochambeau’s grenadiers and chasseurs, almost 1,200 troops, on board, and fought a Royal Navy squadron under Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot off Cape Henry on 16 March before returning to Newport by 26 March 1781. Again it is unknown why the sale of the captured slaves was advertised almost 10 weeks later for 13 June, but it may well have been connected with the departure of French forces: around 5:00 a.m. in the morning of 10 June 1781, the first Brigade of French forces had begun to embark on vessels in the harbor of Newport that took them to Providence. Or maybe French officers had had their pick and the remaining slaves were sold on the “open market” as the case may be.

Other French officers besides Rochambeau and Closen were acquiring, or had already acquired, slaves as well. Rochambeau’s chief medical officer Jean-François Coste[4] had bought himself a slave as well: we know that since the young man ran away at the encampment in White Plains. Rochambeau’s Livre d’ordre records for 16 July 1781:

Il a deserté un petit negre appartenant a Mr Coste ce negre est petit d’un esoir Chuir ( ?) Begagye porte un habit Rougeotre avec parament et Revers blancs

It has deserted a little (young) negro belonging to Mr Coste this negro is young/small, of a (?), studders, has on a reddish coat with facings and white lapels

Identifying the “Chevalier Dillon” who likely purchased a female slave (or had a black female servant) around that time is more difficult. François Théobald Dillon, born 1764, served as a sous-lieutenant in Lauzun’s Legion and aide-de-camp to Chastellux; Guillaume Henri, born 1760, served as a captain in the Legion and the third brother Robert Guillaume, born 1754, served as Lauzun’s colonel-en-second, his second in command. For reasons unknown the buyer, if this is what happened, had his new property checked out by Dr. Tillinghast. The slave auction took place on 13 June; Dr. William Tillinghast’s “Account Book” contains an entry for 14 June 1781 for treating “Monsr Chevalier Dilands negro Woman”. The entry is repeated on 16 June.[5] The date may be purely coincidental, but Robert Guillaume is the most likely candidate for the “Chevalier Dillon.” Dillon had accompanied Lauzun on the Spring of 1779 campaign to Senegal where Fort St. Louis fell on 11 February 1779. In his Mémoires, Pontigaud de Moré tells of a love-affair of Dillon with the wife of the King of Cayor, “aussi belle que la plus belle negresse”.[6]

Newspaper advertisement for a slave auction to occur at a wharf in Newport on June 13, 1781 sponsored by the French military. The advertisement appeared in the June 9, 1781 edition of the Newport Mercury.

How did Destouches “capture” these slaves? Mostly by accident, it seems. Some, if not all, of these slaves formed part of a group that had run away from their owners in the spring of 1781 when they learned of the arrival of Crown forces under Benedict Arnold in Virginia. Their plight occupied the Rhode Island court system ten years later.[7] According to court documents, the slave named Robert who initiated the legal proceedings ran away from his owner in early in 1781, leaving behind his enslaved mother and father. Robert hailed from Port Royal in Caroline County, Virginia (an incorporated town with a population of 126 according to the 2000 census on the Rappahannock River about 20 miles south of Fredericksburg). Robert and the other slaves probably hoped to obtain his freedom by serving in the British army during the American Revolution. Making his way down the Rappahannock, Robert, along with some fellow runaways, boarded one of Admiral Destouches’ vessels stationed in the Chesapeake Bay. Perhaps Robert and the others thought that their chances of securing freedom would improve by boarding a French vessel but it is more likely that they mistook the French vessel for a British ship. Either way, boarding the French vessel did not mean freedom but rather more years in slavery. Destouches brought the slaves to Newport—where based on a 1774 Rhode Island law forbidding the importation of slaves they should have been freed.

Destouches was probably unaware of that law but Rhode Island and Newport authorities should have been and thus should have prohibited the sale. They did not. Maybe they did not want to annoy their “illustrious ally.” (Though it is possible Rhode Island courts would have ruled that “property” captured during war was not subject to the importation prohibition.)

On 13 June the sale went ahead as planned. After trading bids with Henry Sherburne, Newport baker Godfrey Wainwood purchased Robert for 170 Spanish silver dollars, the same price Rochambeau had paid for his slave a few days earlier. In 1789 a dispute arose over the length of the contract Robert was supposed to work for Wainwood; Wainwood claimed nine years, Robert claimed seven years. After lengthy legal proceeding it was in the fall of 1791 that Robert was finally “[wrested] from the iron grasps of despotism and [restored] to the capacity of enjoying himself as a man.”[8]

Coste’s slave, as we have seen, ran away outside New York City in July 1781 and the fates of Rochambeau’s and Dillon’s slaves are unknown. But if any of them did accompany their owners to France they would almost certainly have become free. Even though France was actively engaged in the slave trade and permitted slavery in her colonies, in France proper slavery of any kind was illegal since the Middle Ages, when King Louis X had decreed on 3 July 1315 that “According to natural law all men are born free.”[9] Louis’s decree was upheld and reconfirmed repeatedly by French courts, the parlements, on the grounds that France, described by the Parlement of Guyenne in 1571 as “the mother of liberty,” cannot allow slavery on her territory. In 1716, the Regency published an edict permitting colonials to bring their slaves to France under certain conditions, i.e. as servants or to learn a craft, but they had to be returned to colonies within a certain number of years. If not, the slave would become free. The next decades saw numerous—failed—attempts by planters in the French colonies to tighten the slave laws in and for France proper, i.e., in 1723 and 1724, and on 15 December 1738 a Royal edict set the time limit for residency of slaves in France to three years and tightened bureaucratic controls. Since the Parlement of Paris which held jurisdiction over almost 2/3 of continental France did not register these decrees, they were not valid in almost 2/3 of continental France. On the contrary, the Parlement made it a point to manumit any slave asking for his/her freedom. Responding to complaints by planters that there was a virtual network of support for their slaves assisting them in gaining freedom the moment they stepped ashore, Choiseul in June 1763 asked Colonial administrators in the Caribbean not to allow any blacks to embark for France; on 9 August 1777, a Royal decree published expressly forbade the importation of any free black or slave into the kingdom; those who were still in France were to be sent back to colonies. This decree the Parlement of Paris registered and surely Rochambeau and his officers knew the law before they purchased or otherwise acquired black servants and/or—but apparently were prepared to ignore it.[10]

While French forces quartered in Virginia in 1781/82, slaves frequently sought French protection,[11] but in at least one case a slave used the presence of French forces in Connecticut to gain his (temporary?) freedom. On 6 June 1781, Samuel Talcott Jr of Hartford sent Jeremiah Wadsworth his “Negro Man Addam”. Addam had told Talcott “that A French General Lodging at Mr Caleb Bull Junr Wants to hire him as an attendant and will Clouth him and Give Good Wages he says he doth not know wheather the General Wants to Buy [him].” Talcott preferred to sell Addam – he “don’t want the fellow but I want Money” and asked Wadsworth to take over the task of selling Addam. Addam took the letter and may, or may not, have returned to Bull’s Tavern. He certainly did not go to Wadsworth since on 26 June Talcott told Wadsworth that Addam “hath since disappeared” and asked Wadsworth’s assistance in recovering his slave.[12] There is no evidence that Addam returned to his owner.

Africans had served in the armed forces of France since the late 17th century, most recently in the spring of 1779, when Capitaine Vincent was instrumental in recruiting black volunteers for Admiral Charles d’Estaing. In August 1779, the 545 black men of the Chasseurs Volontaires (and 156 white Volunteer Grenadiers) set sail for the American mainland, where they took part in the failed siege of Savannah in October. The following spring, a company of these chasseurs, some 60 men strong, were the sole French troops participating in the defense of Charleston, South Carolina, where they were taken prisoner. Quite possibly their captors sold them back into slavery in the Caribbean: the sale of captured Blacks, formerly, slaves, or run-aways, was common practice on all sides.

When the comte de Rochambeau’s expeditionary corps stepped ashore in Newport in June 1780, it counted at least one black soldier in its ranks: Jean-Baptiste Pandoua from Madagascar, who had joined the Bourbonnois regiment as a musician in January 1777. He deserted on 27 October 1782 while his regiment was quartered in Connecticut.

It is unknown whether Captain Mathieu Dumas, aide-de-camp to Rochambeau and later aide-major général des logis (assistant quartermaster-general), owned a slave as well or whether he had hired the black man in this portrait painting by Albane. When in Newport Dumas lodged with Joseph Anthony in Spring Street. (The house is no longer standing.) Doniol identifies the painting as having been executed in Providence in 1780.[13] When in Providence Dumas, stayed with Deputy Governor William Bowen.[14] Bowen’s house was torn down in 1850.[15]

Other officers hired free blacks as servants, most of whom remained in the United States. If they lived long enough their names appear in pension applications of the 1820s and 1830s, viz., Jacob Francis:

On this Ninteenth day of June in the year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine Personally came and appeared before Richard Riker Recorder of said city; Jacob Francis a couloured man who made solemn oath that he is now about Sixty years of age, that during the War of the Revolution he was a servant in the French Army under the command of Rochambeau, that he was present at Little York in Virginia at the taking of Cornwallis, and although a Boy of Twelve or Thirteen years of Age he perfectly well remembers seeing Edward Coleman … And further this Deponent saith not.

Jacob hisXmark Francis[16]

Baron Closen, on the other hand, whose black servant Peter had been “born of free parents in Connecticut,” accompanied him to Europe in 1783.[17]

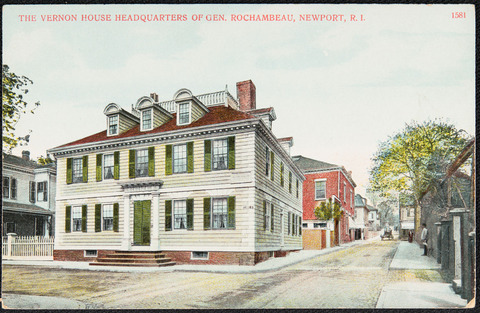

Postcard, ca. 1907, of the Vernon House at the corner of Clarke and Mary Streets in Newport. General Rochambeau stayed at this house during his time in Newport and built a temporary extension that he used as his office to meet outsiders (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

The comte de Rochambeau did not have the opportunity to bring the enslaved man he had purchased back to France. On July 24, 1781, after the French Army had been operating with the

American Army in Westchester County north of British-occupied Manhattan Island since 21 July in what is known as the Grand Reconnaissance, the enslaved man (whose name is not known) self-liberated himself by escaping to British lines. Not only that, he provided the British with useful intelligence. At the time, the French and American armies for several days had been aggressively approaching British Army outposts north of Manhattan Island and hoping (without any luck) that a British Army force would march out to meet it. At 8:30 a.m. on July 24, a Hessian officer wrote a note informing the recipient that “A negro servant to Mr. la Comte de Rochambeau, who came in this morning, says that they [the French Army] had no Baggage with them, that they did not strike their Tents in the Camp at White Plains, that the artillery park, Baggage, etc. was left there [at White Plains] under a Camp Guard, and that the whole [French] Army which had been down here, was certainly marched back to their old position.” The intelligence persuaded the British that the operations of the allied armies had been intended only as a reconnaissance mission and not an attempt to lay siege to New York City.[18] Pursuant to the Philipsburg Proclamation published by the British commander in chief, Sir Henry Clinton, on June 30, 1779, the formerly enslaved man was now free.[19]

Notes:

[1] Musée de Rennes, Les Français dans la Guerre d’Indépendance Américaine (Rennes, 1976), p. 83. I have not seen this “Acte du vente d’un negre au Compte de Rochambeau, Newport 5 June 1781”, which in 1976 was owned by the marquis de Rochambeau. The identification in the exhibition catalogue that « la Molli » was captured by Admiral Barras is wrong: the frigate La Concorde carrying Barras left Brest on 12 April, only arriving in Boston on 8 May 1781. [2] P.G.R., ”Le contre-amiral LeGardeur de Tilly. “ Bulletin des recherches historiques, vol. 9 no. 6 (June 1903), pp. 189/90. [3] See also Tilly to Washington of 15 March 1784, in which he wrote of “Leveillé et Deux frégate avec Lesquels je me Suis Rendüe Maitre Du vaisseau Le Romulusse, Le Duc De york, La Goilétte La Revange Et plusieurs Austre petits Batiments Dont je Remie Les prisoniers.” http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0161 [4] See Louis Trenard, “Un défenseur des hôpitaux militaires: Jean-François Coste” Revue du Nord vol. 75, Nr. 299, (January 1993), pp. 149-180, and Raymond Bolzinger, “A propos du bicentenaire de la guerre de l’Indépendance des États-Unis 1775-1783: Le service de santé de l’armée Rochambeau et ses participants messins,” Mémoires de l’Académie Nationale de Metz vol. 4/5, (1979), pp. 259-284. [5] Tillinghast Account Book, 1777-1785. Vault A, Shelf no. 6, call no. 1313, Newport Historical Society. [6] Surprised by the King’s prime-minister during a rendez-vous in her tent, Dillon was saved from certain death by the Queen’s confidante who threatened to shoot him (with Dillon’s pistols) if he entered the tent before he had received the queen’s permission. Charles Albert comte de Moré, chevalier de Pontgibaud, A French Volunteer of the War of Independence, Robert B. Douglas, trans. and ed. (Paris, 1898), pp. 113/14.See François William van Brock, “Le Lieutenant General Robert Dillon,” Revue historique des armées (1985), pp. 14-29, p. 17; an English translation was published in The Irish Sword, vol. 14, no. 55 (1980), pp. 172-187. See also J. Monteilhet, « Le Duc de Lauzun, gouverneur du Sénégal, janvier-mars 1779 » Extrait du Bulletin du Comité d’études historiques et scientifiques de l’Afrique occidentale française no.1 (January-March 1920), pp. 193-237; Lauzun’s « Journal du Sénégal » is published in ibid., pp. 515-562.

[7] The following paragraphs are based on the description of Robert’s case at http://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/damiano/background%206-10.html#18See also John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Baltimore, 2003), p. 61.

[8] Providence Abolition Society Minute Book, 18 November 1791, Rhode Island Historical Society, quoted at http://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/damiano/background%206-10.html#18. While his case wound its way through the court system, Robert lived as a free man with various families in Newport. See the account book of Thomas Robinson 1753-1794, p. 195 with an entry of August 1790 regarding Robert. Vault A, Shelf no. 19, call no. 490, Newport Historical Society. [9] Ordonnances des Rois de France (Paris, 1723) vol. 1, p. 583 : « Comme selon le droit de nature chacun doit naistre franc. » Ordonnances des Rois de France (Paris, 1723) vol. 1, p. 583 : « Comme selon le droit de nature chacun doit naistre franc. » http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1181592/f639.image. The theme is expertly covered in Sue Peabody, There Are No Slaves in France: The Political Culture of Race and Slavery in the Ancient Regime (Oxford, University Press, 1996) and in the collection of primary sources by Pierre H. Boulle and Sue Peabody, Le Droit des Noirs en France au Temps de l’esclavage Textes choisis et commentés (Paris, 2014). [10] At any given point there were probably fewer than 2,000 blacks in France, 75% or more of them living in Paris. In February 1782, Navy Minister Castries formed a legislative committee tasked to find out the numbers and status of blacks in the kingdom. [11] Virginians were convinced that French officers were hiding their slaves by claiming them as their servants, trying to spirit them out of the state. In a letter to Governor Harrison of May 1782, William Dandridge claimed that one of his slaves, a “very likely and valuable fellow” was employed by a French Major who refused to turn him over since the man claimed to be a freeman, and he had therefore a right to employ him. Since then that slave had disappeared only to be replaced by another run-away. Calendar of Virginia State Papers and other Manuscripts vol. 3 (Richmond, 1883), p.183. The issue is expertly treated in Samuel F. Scott, “Strains in the Franco-American Alliance: The French Army in Virginia, 1781-82” in: Virginia in the American Revolution, Richard A. Rutyna and Peter C. Stewart, eds. (Norfolk, 1983), pp. 80-100, and Yorktown to Valmy, pp. 79-80.There is evidence that some French officers, especially in the confusion following the surrender at Yorktown, did indeed spirit Blacks on board some of de Grasse’s ships and transported them to the Caribbean where they were sold as slaves onto the sugar plantations.

[12] The letter with the postscript is in Jeremiah Wadsworth Papers, Box 131, Connecticut Museum of Culture and History, Hartford, CT. No other correspondence relating to this incident has been found. The unidentified officers most likely stayed at “Bull’s Tavern at the Sign of the Bunch of Grapes,” strategically located across from the State House in Hartford in the eighteenth century. In January 1781 the chevalier de Chastellux stayed there. Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781, and 1782, Howard C. Rice, Jr., ed., 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, 1963), vol. 1, p. 229. The site at 777 Main Street is occupied today by the Fleet Bank Building but a historic marker commemorates the tavern. [13] J. Henry Doniol, Histoire de la participation de la France à l’établissement des États-Unis d’Amérique, 5 vols. (Paris, 1886-1892), vol. 3 p. IX, fn 1. [14] Mathieu Dumas, Memoirs of his own Time; including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration, 2 vols. (London, 1839), vol. 1, pp. 32-33. [15] Howard W. Preston, “Rochambeau and the French Troops in Providence in 1780-81-82,” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, vol. 17, No. 1 (January 1924), p. 8. [16] Included in Pension Application R2160 of Edward Coleman, “a coloured man” enlisted in the Company commanded by Captain Sinclair, in the regiment commanded by Colonel Mayhem or “Maiham,” i.e., Hezekiah Maham, 3d SC Regt. In 1829 both men lived in New York City. [17] Acomb, Evelyn, ed., The Revolutionary Journal of Baron Ludwig von Closen, 1780-1783 (Chapel Hill, 1958), p. 187.[18] [Captain Ludwig August] Marquard, aide-de-camp of General Wilhelm Reichsfreiherr von Innhausen und Knyphausen], to Major James DeLancey, July 24, 1781, Morris’s House, in Sir Henry Clinton Papers, vol. 166, item 25, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. I thank Todd W. Braisted for bringing this letter to my attention. For more on the late July 1781 operations, see Acomb, ed., Journal of Baron Ludwig von Closen, pp. 97-102; and Diary of Frederick Mackenzie, Giving a Daily Narrative of His Military Service as an Officer of the Regiment of Royal Welch Fusileers During the Years 1775-1781 in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930), vol. II, pp. 572-73.

[19] The proclamation was first published in James Rivington’s New York Gazette, July 21, 1779.