Born in Yorkshire, England in 1716 (some sources say 14 June, others say 27 July), Peter Harrison was placed at age twelve in an apprenticeship to architect/builder William Etty. He lived at Newport, Rhode Island from about 1745 until his death (with part-time residence at New Haven, Connecticut 1766-1775). He became arguably the greatest architect who ever lived in America, with about 450 buildings and numerous examples of the finest furniture to his credit, and was the first architect to design buildings on every known continent, but is little known today because nearly all his papers were destroyed during the American Revolutionary War.

In England, when Harrison was seventeen, and only a year from the end of his training, he and his family were having lunch with their friend Wentworth, Marquess of Rockingham, whose three-year-old son later became twice the Prime Minister, and Wentworth airily set Harrison an exam to design a country house six hundred feet long. Wentworth liked the design so much that he built it, and Wentworth-Woodhouse in Yorkshire is still the largest private house in Europe. Harrison’s achievement in architecture is parallel to the early work of precocious composers Handel and Mozart.

Etty, who advised Harrison not to charge for designing churches or other public buildings, died just as Harrison was finishing his apprenticeship. Harrison began his independent career by designing some splendid churches and other public buildings, but relatively few private buildings for which he could have been paid. He therefore asked his older brother Joseph, a merchant-ship captain, to teach him the ways of the sea so that he could earn a living. Thus it was that he found himself in command of a ship sailing to the Americas at age twenty-one in 1738, after having visited Venice and seen buildings of the great Andrea Palladio and Baldassare Longhena in person.

At his first port of call, Paramaribo, Suriname, he designed two churches, a synagogue, and the governor’s mansion, and at Bridgetown, Barbados, he designed the courthouse, a synagogue, and a business building. In Jamaica, he designed two plantation houses. In South Carolina, he designed the iconic Drayton Hall Plantation, and enlarged the governor’s mansion at Charleston. In North Carolina, he designed the colony house/market at Wilmington, and in Virginia the iconic Stratford Hall Plantation on the Potomac River. In Maryland, he designed Poplar Hill and two other mansions, and at Philadelphia he designed Belmont and four other plantations, as well as America’s first neo-Palladian furniture, a cabinet for the Library Company. At his last port of call, Boston, he designed the iconic steeple for Christ Church, “Old North” where Paul Revere’s lanterns would later be hung, and drew the first ever block-front furniture for Job Coit to make—a secretary-desk now at the Winterthur Museum. Such a record of distinguished designs would normally be enough for an architect’s entire lifetime, but Harrison was just getting started.

He made several more voyages to the New World in the next few years, stopping at Newport, Rhode Island long enough to design a beautiful new steeple for Trinity Church, and visiting the French fortress-city of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. There he made friends with the local architect, Colonel Etienne Verrier, and helped him solve a major problem with the main gate building. Verrier gave him an introduction to officials at Quebec and Montreal, where he designed important buildings. In 1744, he was crossing the Atlantic commanding the vessel Nancy when he was captured by Captain Pierre Morpain and the schooner Le Succes. War had again broken out between Great Britain and France, so Harrison returned to Louisbourg as a prisoner of war, and he was placed under house arrest at Colonel Verrier’s house as being preferable to a stay than in the squalid dungeon.

At Verrier’s house, he came across the complete plans of the fortress and copied them onto paper that he hid in the lining of his coat. He also had time to consider how to make practical flush toilets; he fitted the world’s first ever WCs to Verrier’s hospital building. Thirty-six of these new toilets were also included in Harrison’s 1745 design for the eighty-two-bed Liverpool Infirmary, the first in the world in a new building. The technology required inventing the familiar S-shaped exit valves, exhaust stacks, and ship-style pumps to bring the water into giant overhead cisterns.

After his release, Harrison showed the fortress plans to his friend Governor Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire and also to Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts. They used the plans to persuade their legislatures that it was safe to attack Louisbourg with no more than armed farmers and fishermen and no British troops; they captured the place in June 1745. The capture was a big surprise on both sides of the Atlantic, but the event is little known today. Shirley was convinced that the capture of Louisbourg was responsible for preventing the French from successfully capturing all of British America

Rhode Island officials then had Harrison design the impressive Fort George on Goat Island at Newport, but it was never completed because the war had ended. The following year, Harrison married Elizabeth Pelham of Newport, one of the wealthiest women in New England, and he built her a handsome mansion on a bluff overlooking the harbor, Leamington Farm, on Harrison Avenue (of course), a house that still stands, although moved inland about 100 meters and greatly altered and enlarged.

In 1660, French King Louis XIV falsely imprisoned Nicolas Fouquet, his genius finance minister, who had been able to cover like magic any enormous debt that the king incurred. After the fall of Fouquet, no one else—not even the great Jean-Baptiste Colbert—knew how to cover the debts, so France was forced to borrow increasing amounts from bankers in Amsterdam. They never did figure out how to resolve their deficits, so that by 1789 when the bankers foreclosed it sparked the fuse that began the French Revolution. Back in the 1740s, French military chief, Marshal Maurice Saxe, proposed solving the deficit by seizing Britain’s colonies around the world. The French had a brilliant plan: they gave a large sum of money to Bonnie Prince Charlie, grandson of discredited British King James II, to enable him to invade Britain, and when the British predictably brought their soldiers home from the colonies to defend the home country, the French captured most of India and started their invasion of North America. The capture of Louisbourg stopped the French invasion dead in its tracks. At the peace conference in 1748, France returned most of India in return for Louisbourg. Therefore, it is no exaggeration to say that Americans speak English today and not French, and India remained in the British Empire for two hundred more years really because Peter Harrison had displayed the courage and initiative to copy the plans of Louisbourg.

Obviously, such a man should be rewarded. Shirley became his patron and wrote letters to all the other British colonies, suggesting that they should show their gratitude by commissioning Harrison to design colony houses, governor’s mansions, churches, courthouses, colleges, and other public buildings, which they did. Shirley himself had Harrison design his own mansion, Shirley Place in Roxbury, as well as the rebuilding of the Massachusetts colony house, and the new King’s Chapel. Shirley gave Harrison a diplomatic passport, technically to the peace conference, but he told him to use it to travel around France looking at architecture, which he did. When Shirley was later reassigned to be Governor of the Bahamas, he had Harrison design his mansion there at Nassau, a church, the market, and three versions of the colony house (small, medium, and large, depending on how much the legislature would want to spend; as it happened, all three were eventually built), and Shirley’s son, governor of the island of Dominica, had Harrison design his governor’s mansion and three versions of the colony house.

At Shirley’s suggestion, Harrison designed governor’s mansions, colony houses and/or courthouses in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Jamaica, British Virgin Islands, Saint Kitts, Nevis, Antigua, Montserrat, Saint Vincent, Grenada, and Tobago. The invitations kept coming after the next war, for he was asked to design governor’s mansions and colony houses for Quebec City, Montreal, British East Florida, British West Florida, British Guadeloupe, British Martinique, and Senegal. He was asked to design buildings for many colleges, including Dartmouth in New Hampshire and Burlington in what become Vermont, Harvard in Massachusetts, Brown in Rhode Island, Yale in Connecticut, King’s/Columbia in New York, Princeton and Queen’s/Rutgers in New Jersey, Penn in Pennsylvania, Maryland College in Maryland, Virginia College in Virginia, the College of Charleston in South Carolina, and Whitefield College in Georgia. He designed hospitals in New York and Pennsylvania, and prisons in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and Pennsylvania. Harrison court houses appeared in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Jamaica, and Harrison markets appeared in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Virginia, [Spanish] Louisiana, Bahamas, Jamaica, and Britain. Harrison theatres were built in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, South Carolina, Louisiana, Jamaica, and India.

At Shirley’s recommendation, Harrison was invited to come to London for recognition. He stopped first in Dublin, where Archbishop Arthur Price (upon his death in 1752, Price was the man who gave his servants, the Guinness family, his top-secret family recipe for stout, as well as money to build their own brewery!) commissioned Harrison to design a new cathedral, three parish churches, twelve schools, two customs houses, two hospitals, the Provost’s House at Trinity College, and a town hall. He then sailed to Liverpool, where he was commissioned to design three churches and the impressive Town Hall. When he reached London, Prime Minister Henry Pelham (a cousin of Harrison’s wife) had him design one building each at Oxford and Cambridge; King George II had him design part of Dublin castle and two buildings in his native Hannover; Lord Mayor William Beckford of London commissioned three important buildings (one of which, the new British Museum with three domes, was never built because a new war was by then brewing with France); High Sheriff Bourchier Cleeve of London had him design a Palladian domed house, Foot’s Cray; and the Spencer family commissioned Spencer House in London, where Princess Diana grew up. Shirley’s cousin had him design his new house, Staunton Harold Hall, and a Wentworth cousin had him design the new wing of Wentworth Castle (which Horace Walpole described as the most tasteful piece of architecture in Britain). The British East India Company had benefitted enormously from Harrison’s initiative, so Chairman Richard Chauncey commissioned him to design important buildings at Saint Helena; at Bombay, Surat, Cuddalore, Madras, Vizagapatam, Calcutta, and Patna in India; Bengkulu in Java; and the church and almost all the “Hongs” for thirteen different trading nations at Canton, China.

For Shirley Place near Boston, Harrison assumed that such a house should be built of formal rusticated stonework, but Governor Shirley told him that there were no stone quarries yet in Massachusetts and no workmen who would know what to do with stone. Harrison solved the problem by proposing to clad a wooden-frame house with thick wooden planks carved to look like stonework. Harrison’s invention of wooden rustication quickly spread throughout the colonies, the second surviving example being the temple-shaped Redwood Library, perched like an acropolis overlooking Newport Harbor.

The Redwood Library, built about 1749 and designed by Peter Harrison, still functions as a library today.

When the next war broke out against France (what is known in America as the French and Indians War), people were terrified that the French were about to invade at any moment. The Virginia Legislature sent its youngest member, George Washington, twenty-three years old, to Boston to see if Governor Shirley had any helpful ideas. While he was there, he marveled at Shirley’s new house. Washington was about to build his own wooden house, Mount Vernon, and wished to imitate the wooden stonework for his own house, so Shirley showed him how it was done. Harrison was not asked to design Mount Vernon, because Washington already had two friends who were architects, and one of them, John Ariss, was selected.

Early in the French and Indians War, the future Prime Minister Wentworth, Marquess of Rockingham, recommended Harrison’s older brother Joseph for the mostly ceremonial position of Customs Collector for New Haven, Connecticut in 1757, so Harrison drew the plans for a three-story rusticated wooden custom house with an arcaded market on the ground floor to be built on Long Wharf. This building was destroyed by the mob led by Isaac Sears in April 1775 after news arrived of the battles at Concord and Lexington.

When Harrison had been visiting France, he was impressed at the shapes of some of the French furniture, so as soon as he got back to Newport he drew designs inspired by the French furniture for John Goddard to make—one of Goddard’s tea tables in that style sold at auction in 2005 for $8.4 million, the highest price ever paid for a table. Goddard encouraged Harrison to design more furniture for him, and the Rhode Island and Connecticut versions of the block-front were a result. Other Rhode Island furniture makers, such as the Townsends and Grindall Rawson, also made these block-fronts, and one such Rawson secretary desk sold at auction in 1989 for $12.1 million, the highest price ever paid for a piece of wooden furniture up to that time. For John Townsend, Harrison invented “stop-fluting” for furniture legs and bedposts as his own trademark. Harrison also imported the first bombe furniture from England, and designed examples of that exclusively for Massachusetts craftsmen, such as Benjamin Frothingham. Samuel Loomis and Benjamin Burnham were the chief Connecticut craftsmen who followed his special designs.

While Rockingham was in his first term as Prime Minister, he promoted Joseph Harrison to Customs Collector for Boston (a thankless job), and so he appointed Peter to take his brother’s place in New Haven in October 1766. Peter was glad to move there part-time, because it was close to New York City, where he was receiving numerous important architectural commissions. The only three to survive out of about thirty are Saint Paul’s Chapel (where George Washington had his inauguration service), the governor’s mansion on Governor’s Island, and Erasmus Hall School in Brooklyn. Among his many designs were America’s first gothic revival buildings, for Trinity Church.

Yale College being a hot-bed of revolutionary activity, crowds of demonstrators led by Benedict Arnold (who was a cousin of Elizabeth Harrison) frequently assembled in front of Harrison’s house to demand that he tell the British government to change its policies, but he protested that he knew nobody then in the British government. In between demonstrations, Harrison designed a handsome waterfront mansion for Arnold (a leading rum smuggler), which had a view of the harbor and the custom house/market.

In 1768, both Harrison brothers were given the prestigious award of a free membership in the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. No note survives as to why they received the award, but it seems that Joseph owned America’s finest telescope and Peter rebuilt the so-called Old Stone Mill in Newport as an observatory for the 1769 Transit of Venus.

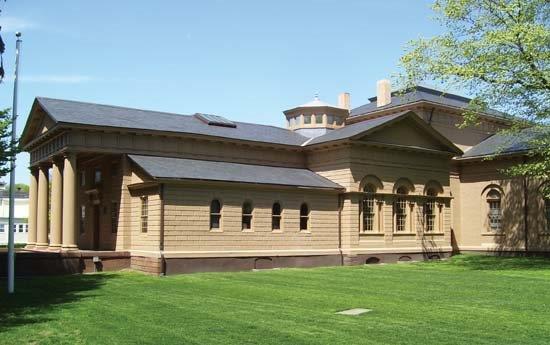

In addition to houses large and small, Harrison designed cathedrals, churches, chapels and synagogues (for nine of the thirteen major denominations of the day), as well as Masonic Halls, mansions for governors, intendants, and Indian chiefs, colony houses, courthouses, markets, hong buildings, exchanges, libraries, theatres, assembly rooms, custom houses, schools, colleges, hospitals, orphanages, town halls, livery halls, prisons, forts, barracks, lighthouses, gazebos, stables, follies (whimsical structures), a tavern, an observatory, a Venetian palazzo, and one “joke” house for artist William Hogarth. Some of his best known buildings include the First Baptist Meeting House (1774-75) in Providence and the Redwood Library (1748-49), Touro Synagogue (1759-63), and Brick Market (c. 1760) in Newport. In addition, they include King’s Chapel, Boston; Christ Church, Cambridge Massachusetts; Johnson Hall, Johnstown, New York; Saint Paul’s Chapel, New York City; the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the steeple of Christ Church, Philadelphia; Saint Michael’s Church, Charleston, South Carolina, and Saint Paul’s Church, Halifax, Nova Scotia. He designed mostly in the classical neo-Palladian style that had been popularized by Lord Burlington, and was he one of the most proficient practitioners of the style in the world. In spite of all this, Harrison is surprisingly not listed in the late Sir Howard Colvin’s Biographical Dictionary of British Architects. Harrison’s designs are frequently attributed to other people because he always left construction supervision in the hands of others.

The First Baptist Meetinghouse, designed by Peter Harrison, was the largest building in New England when it opened in 1775.

Although he may not have known all of them personally, Harrison worked as a contemporary to American painters Robert Feke, John S. Copley, and Benjamin West; cabinet-makers John Goddard, John Townsend, and Benjamin Frothingham; sculptor Patience Lovell Wright; silversmiths Benjamin Brenton, Myer Myers, and Joseph Richardson; composers James Bremner, Josiah Flagg, William Tuckey, and William S. Morgan; actor David Douglass; scientists Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rumford; and statesman Stephen Hopkins.

Harrison designed five different size projects for the Maryland colony house in 1770; the largest of them became, I believe, the basis of the plans for the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. in 1792. His impressive campus for Virginia College at Kemp’s Landing in 1772 (blown up by Patriot forces in the Revolution) was imitated by Jefferson for the University of Virginia in 1817.

When news reached New Haven of the battles of Concord and Lexington in April 1775, Benedict Arnold took the gunpowder from the local magazine and hid it, and then rode with his regiment to the Boston area to see what he could do to help. That left the New Haven mob, led by New York escaped criminal Isaac Sears free to burn the custom house/market and try to lynch Harrison. However, after Harrison had died of a heart attack on 30 April 1775 when he saw the mob preparing to lynch him, Sears organized the systematic destruction of all Harrison’s valuable furniture and papers—architectural drawings, contracts, correspondence, account books, sketch books, and note books. Meanwhile, the fast-moving Arnold had already captured the first warship for Continental service at Lake Champlain in upstate New York. That explains why it has taken so long to find what can be known about Harrison.

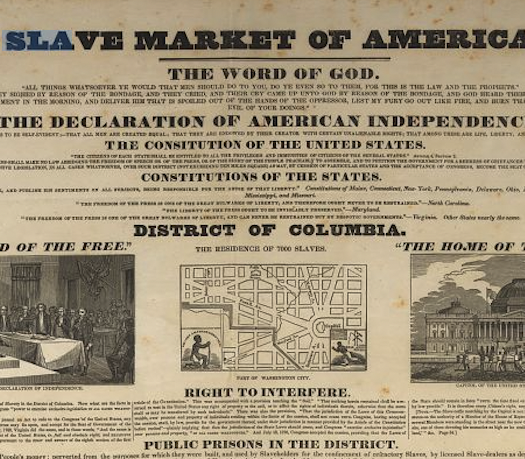

[Banner Image: The Brick Market on Thames Street in Newport, designed by Peter Harrison around 1760, now the home of the Newport Historical Society’s Museum of Newport History and gift and book shop.]For Further Reading:

The late Dr. Wendell Garrett asked me (then a freshman at Harvard in 1962) to begin research on Harrison. The research has eventually resulted in two books: The Buildings of Peter Harrison: Cataloguing the Work of the First Global Architect 1716-1775, published in 2014 by McFarland & Company, Inc. (P.O. Box 701, Jefferson NC 28640; ISBN 978-0-7864-7962-7), priced at $75, and mostly text with few illustrations, and Peter Harrison (1716-1775) Drawings, published 2015 by Thirteen Colonies Press (710 South Henry Street, Williamsburg VA 23185-4113; ISBN 978-0-934943-09-3), priced at $39.95, mostly line illustrations with brief text. Both are available from your local booksellers or from Amazon or from my website www.historicarchitecture.guru. These are among the most significant volumes published on early American architecture and decorative arts in many years. The present book, Peter Harrison Supplement, is available from Thirteen Colonies Press only, and is intended to be supplied at no charge (except shipping) to anyone who has bought one of the other two books.