[Note from the Editor: The following piece, celebrating Pettaquamscutt Rock in South Kingstown, was penned in 1958 by William D. Metz, who starting in 1945 and until his retirement in 1982 served as professor of history at the University of Rhode Island. He was also the driving force behind the founding of the Pettaquamscutt Historical Society and was instrumental in acquiring the old Washington County Jail in Kingston as its headquarters. He was president of the South County Museum for fourteen years and helped to relocate it to its current site in Narragansett, where a building is named for him.

This piece is worthwhile in its own right, but it was also a product of its times. While Professor Metz was sympathetic to the plight of local Indians losing land to voracious whites, most current historians would be even harsher on whites. In addition, Professor Metz reveals a strain of patriotism that was then common, at a time when many thought that democracy was in a life or death struggle with international communism. Professor Metz, a mentor to me when I was a teenager, passed away in Kingston in 2013 at the age of 98. I thank his daughter, Elizabeth McNab, for bringing this article to my attention and allowing it to be published.

Today, Pettaquamscutt Rock is even more overgrown than in 1958, but it still affords a spectacular view overlooking Narrow River. Its face, approximately fifty feet high and forty feet wide, is sometimes climbed by rock climbers. It is in a South Kingstown town park called Treaty Rock Park on Middlebridge Road (below the Observation Tower on Tower Hill).]

Rocks, even large large rocks, are not unusual in Rhode Island The uninitiated might therefore well ask why we should gather here today to mark this particular rock. Pettaquamscutt Rock or Treaty Rock, which, though it towers high above us, has been so obscured by the trees that few among us knew its location before today. The answers to that question are several.

First let me speak as a historian representing the Pettaquamscutt Historical Society. In the days when the English first settled this country, the land west of Narragansett Bay was quite open, the forests were sparse and free from underbrush, kept that way by the Indians who periodically burned over the region. This great rock, then visible for almost the entire length of the Pettaquamscutt or Mattatuxot River, and easily accessible from the river as well as from the Pequot Path, the main Indian trail just to the west, was a natural meeting place for the Indians. No wonder, then, that it became a spot of significance in the history of this region.

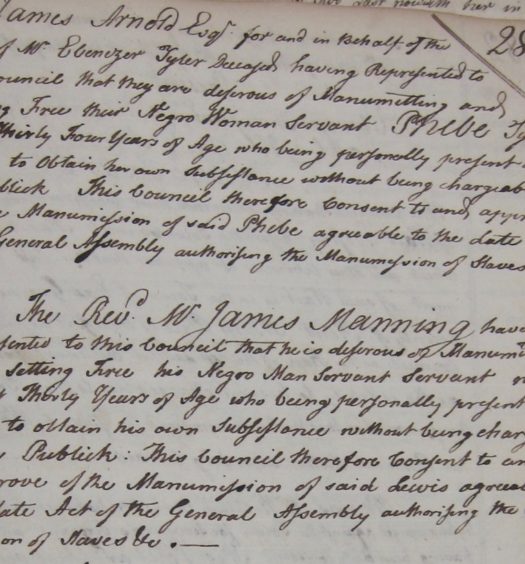

Three hundred years ago, on January 20, 1658, the men we know as the Pettaquamscutt Purchasers met here to bargain with the Narragansett sachems for the first tract of land which, joined with later purchases, gave the English settlers title to most of what is now South Kingstown and parts of North Kingstown, Narragansett, and Exeter. Twenty years earlier, in March, 1638, Roger Williams at this spot had obtained from the great Narragansett sachem, Miantonomi and Canonicus, confirmation of his title to the lands of Providence. On the same day Roger Williams negotiated ‘with the sachems the agreement by which William Coddington, William Dyre, and others obtained all of the island of Aquidneck for forty fathoms of white beads, making possible the peaceful settlement of Portsmouth and, a year later, Newport.

Four years after the Pettaquamscutt Purchase was made, in the spring of 1662, Richard Smith, Jr., Edward Hutchinson, and others of the Atherton Company, a company composed of Massachusetts and Connecticut land speculators, in the presence of 200 or 300 Indians foreclosed the mortgage they held on the lands of the Narragansett Indians and took possession of them by the turf and twig ceremony. The conflict of interest between this group and the Pettaquamscutt Purchasers is obvious. It involved not only private rights to property, but also the question of whether Connecticut or Rhode Island governed this region.

In an effort to settle the dispute, commissioners chosen by King Charles II came to this spot in March, 1665, and, after hearing testimony from all concerned, voided the Atherton claim and declared that this region stretching westward to the Pawcatuck River should be known as the King’s Province with jurisdiction over it vested in the government of Rhode Island. This decision supported by later events and the indefatigable efforts of Rhode Island leaders, preserved the colony from being so reduced in size that it would have been swallowed up by Connecticut and Massachusetts. Going no further in the history than this, and without stretching or padding the record, it seems clear that on this spot occurred events which have affected us right down to the present.

A second reason for marking this great rock is that it reminds us of our noble heritage. As we have noted, Roger Williams, imbued by a strong sense of honesty and Christian justice, and refusing to seize lands from the Indians by mere might as others did, came here to purchase land from them by fair and honorable means. No man of his day was more loved and respected and trusted by the Indians than was Roger Williams. If all white men had dealt with the Indians as he did, this great land of America would have been settled without that tragic price of bloodshed and sorrow that was in fact paid. Again, Roger Williams and others like William Coddington, chief among the purchasers of Aquidneck, came to this region seeking religious freedom. They insisted that man, in his search for God, must be free to follow the promptings of his own heart and mind. The power of government must not be used to coerce men’s consciences, for only the beauty and persuasiveness of God’s love and the truth can gain real and lasting victories over evil and ignorance.

Finally, these men who bargained with the Indians at this spot were men of courage and optimistic faith in the future. They sought no comfortable security as the sole goal of their lives, but pushed into the wilderness with determination and confidence. Through their foresight, hard labor, wise planning, and willingness to take risks, they believed they could better their own condition in life and that of their children after them. On such a spirit has America grown great. This rock, then, stands for the ideals of justice, religious freedom, and courageous use of the opportunities afforded us.

Finally, I am sure that those of you who have climbed the rock have thrilled with the beauty of the view that spreads out up and down along Narrow River and across the low hills far out to sea. Canonicus and Miantonomi, Roger Williams and William Coddington, the Pettaquamscutt Purchasers and the Indian sachems with whom they bargained, the King’s Commissioners, the men of three hundred years ago saw the same sight and responded as we do to its grandeur and loveliness. The emotions stirred within them and successive generations contributed to that love of New England which led them to defend it against all enemies. Our patriotism today is generated in part from this same response to the beauty of the land. As we mark this rock and make it accessible to all, native and visitor alike, we share the glory of our landscape and thus strengthen our loyalty to America.

Why do we mark this rock? The historical record demonstrates it to be the site of events of major importance to this locality. The men who participated in these events represented ideals basic to the American way of life. The beauty of the prospect from the brow of the rock belongs to all men and confirms our love of our country.

[Banner Image: View from the top of Pettaquamscutt Rock]