On March 14, 1964, the Pittsburgh Steelers of the National Football League announced they would hold their training camp that summer at the University of Rhode Island.[1] It was an odd choice since most Rhode Islanders were New York Giants fans, thanks to regional television broadcasts of their games, while the upstart American Football League’s Boston Patriots franchise was entering its fifth season of existence. Moreover, no official NFL preseason or regular season games had been played in the state since the Providence Steam Roller franchise dissolved in 1931.[2]

In 1964, the NFL and the Steelers were far different enterprises than they are today. Thanks to television, the NFL had begun to challenge baseball as the national pastime, but despite a new contract with CBS for $14.1 million a season that would take effect that fall – more than three times the price of their initial pact two years earlier – the average player salary remained nearly unchanged, at $21,000.[3] During subsequent negotiations with the players, the owners agreed to double their contributions to the players’ pension plan, but balked at raising the $50 “salary” that each player received per exhibition game, substituting a $6 per day per diem for the duration of camp.[4]

The Pittsburgh Steelers are now one of the flagship franchises in the NFL, winners of six Super Bowls. But the Steelers entered the 1964 season with a lifetime franchise record of 143-205-16, had finished above .500 just eight times since their debut in 1933, and had qualified for the playoffs only once, in 1947. (In November 1964, Sports Illustrated would run a profile of Steelers owner Art Rooney entitled, “The Winning Ways of a Thirty-year Loser.”) The arrival of Raymond “Buddy” Parker as head coach in 1957 had improved the Steelers fortunes. Parker brought a winning pedigree to the job: he had won an NFL title as a rookie running back with the Detroit Lions in 1935, then led the team to back-to-back championships as head coach in the early 1950’s. He was also a colorful personality, chain-smoking during games and drinking away losses afterwards – sometimes to the point of challenging players to fights while still in a boozy haze.[5] After six years with Detroit, Parker abruptly resigned during a public appearance at the annual “Meet the Lions” preseason banquet, and was named head coach of the Steelers two weeks later.[6] The Steelers flirted with .500 during Parker’s first five seasons before finishing 9-5 in 1962, their best record in 15 years. In 1963 they entered the final weekend of the season with a chance to win their division with a victory over the Giants at Yankee Stadium, but Pittsburgh lost 33-17. Still, there was optimism heading into the 1964 season.

The Steelers had held their training camp at a variety of sites during their first three decades. From 1952 through 1957 the Steelers worked out at St. Bonaventure University in southwestern New York; Art Rooney’s brother Silas, a Franciscan priest, was an alumni and the school’s athletic director.[7] Over the next six years the Steelers trained relatively close to home, staying within 40 to 60 miles of Pittsburgh in accordance with Buddy Parker’s wishes.[8] When the Steelers announced their intentions to move their training camp to URI, Parker claimed the shift was due to a water shortage the previous summer at West Liberty College in Wheeling, West Virginia; the hot, dry conditions left the fields rock-hard and (in Parker’s opinion) caused a variety of minor nagging injuries to the players.[9] Art Rooney agreed to Parker’s request, despite having to spend $40,000 in extra expenses compared with the Steelers previous training camp sites.[10] Besides, Rooney was hardly unfamiliar with Rhode Island – he had been running his thoroughbred race horses at Narragansett Park in Pawtucket for decades.[11] Art’s son Dan had personally checked out the Kingston campus: “I went up to look at it after we played the Giants in New York one time,” Dan told Gene Collier of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2015. “I remember that. Must have rented a car and drove up there. It had great fields, but this is funny, I remember the academicians weren’t too thrilled that we were going to be there. They were like, ‘What are we doing bringing a professional football team around here?’”[12] The younger Rooney also negotiated the terms of the Steelers use of the campus with University President Francis Horn and Athletic Director Maurice Zarchen.

From an official game program, Pittsburgh Steelers versus San Francisco 49ers, September 4, 1965 (Michael Hamel Collection)

The URI Rams football team played its games at Meade Field (now Meade Stadium), a simple facility flanked by bleachers and a concrete grandstand that held a few thousand fans.[13] The Steelers used Meade Field and a pair of nearby practice fields for their workouts, and the players lived in Adams Hall, a four-story brick dormitory that had opened in 1958. At the time, Adams Hall was one of four all-male dorms on campus, conveniently located across the street from Butterfield Hall, a combination dorm and dining hall where the Steelers held their annual opening night dinner, the first official event of camp.[14]

In July 1964 the Steelers began their workouts with a four day passing camp (for quarterbacks and receivers) at the team’s regular season practice facility in South Park, Pennsylvania. On Friday, July 17, Buddy Parker and his staff drove from Pittsburgh to Kingston to get ready for the arrival of the players the following Tuesday – a trip made slightly more challenging because the highway connection between the Connecticut Turnpike and Route 95 in Rhode Island would not be completed until that December. Most of the players flew from Pittsburgh on a United Airlines charter flight into T.F. Green Airport in Warwick.[15] Others took private flights; players could arrange to get picked up at the airport for the 20-mile trip to URI.[16] Over the next seven weeks, the players lived and ate alongside a variety of other temporary residents on campus: students who were taking summer classes, URI athletes who had arrived early for the fall semester for extra practice, and school teachers who were participating in a National Science Foundation summer institute.[17] Parker publically praised the Steelers new summer home as “the best layout (for camp) since I joined the Steelers.”[18]

URI’s location, a few minutes’ drive from Narragansett Bay, provided many opportunities for fun away from football. On the first Sunday of camp, a day off for the players, Parker went fishing with URI head football coach Jack Zilly.[19] Pittsburgh sports writer Roy McHugh wrote that the coaches and players were enjoying their surroundings: “The country around here is pleasing to the eye – wooded and hilly, rocky and full of ponds and small lakes and limestone walls. It has much to offer for a state that is only 30 minutes wide – and Coach Buddy Parker will tell you that the Steelers never had it so good at pre-season training camp.”[20] A week-and-a-half later, the team canceled plans to hold a practice on the beach and instead held a single workout in the morning on campus followed by an afternoon of lounging by the bay.[21] There were plenty of bars and restaurants at nearby Narragansett Pier for the players to frequent, with names like “Carter’s Kitten Club” and the “Beachcomber,” while local movie theatres were showing fare such as A Hard Day’s Night featuring the Beatles.[22]

Back at camp, the players endured a typical program of calisthenics and drills, with plenty of two-a-day sessions designed to get them into shape. Intra-squad scrimmages were held to break up the monotony prior to the start of the official exhibition season. These scrimmages were played with a unique set of rules that remained relatively consistent from year-to-year. Quarters were timed at 12 minutes each. The offense was given the ball on their own 20 yard line whenever they scored or the defense stopped them on downs. The offense scored points in the usual way (6 for a touchdown, 3 for a field goal) while the defense earned 1 point every time they stopped the offense on downs, 2 points for a fumble recovery, and 3 points for an interception. On August 1, the offense defeated the defense 15-10 in front of an estimated 2,000 spectators on the Kingston campus. Quarterback Bill Nelsen threw a 45-yard touchdown pass to Johnny Burrell, and Dave Fleming scored on a 2-yard run. Lou Michaels added a 33-yard field goal for the offense, while Jim Bradshaw scored half of the defense’s points with a recovered fumble and an interception. The fans seemed to enjoy the two-hour session, but their polite applause was a noticeable contrast to the rougher treatment the players were used to receiving back home. Guard Rod Stehouwer told a reporter afterwards that the locals seemed to understand the game, since “they ask you a million questions after each practice,” but that during the scrimmage their reactions were a bit muted. “They act like rich kids,” Stehouwer continued, before engaging in a bit of stereotypical hyperbole: “I guess they really are the Brooks Brother and gin-and-tonic set. They like our game but they just can’t wait for the Newport sailing races to get under way.”[23]

A week later, on Saturday, August 8, the team played an intra-squad scrimmage at Cranston Stadium, a small facility built in 1936. Tickets for the scrimmage were priced at $2 for adults and $1 for kids 12 and under – the adult admission price happened to match the price of a ticket to a semipro Providence Steamrollers football game – and the proceeds benefited the URI and Pittsburgh Steelers Alumni scholarship funds.[24] As an extra incentive, fans were allowed on the field before the game to mingle with the players; star fullback John Henry Johnson drew the most interest from autograph seekers.[25] Between 5,000 and 7,000 spectators, and several Steelers alumni, were in attendance as the offense outscored the defense 18-11. Lou Michaels kicked a pair of field goals from 47 and 26 yards, quarterback Terry Nofsinger scored on a 1-yard sneak, and Bill Nelsen threw a touchdown pass to flanker Bill Barber. The defense countered by earning 8 points for stopping the offense on downs, and 3 points for an interception by Dick Haley.[26] The Steelers regular radio team of Tom Bender and Jack Fleming called the game over the P.A. system as a warm-up for the upcoming season.[27] Leading up to the game, the Providence Journal ran stories about the Steelers alongside brief articles describing the United States military “emergency buildup” in “Viet Nam” following an attack on the USS Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin earlier in the week.[28]

Over the next four weeks, the Steelers went 1-3 in the preseason, including a 48-17 blowout loss against the Baltimore Colts at the third annual Hall of Fame Game in Canton, Ohio (Art Rooney was enshrined into the Hall prior to the game).[29] The game marked the Steelers debut of kicker Mike Clark, who had been picked up from the Eagles a few days earlier as “insurance,” in Parker’s words, due to the recent struggles of incumbent kicker Lou Michaels. Michaels responded to Clark’s arrival by breaking curfew and getting into a fight with teammate Jim Bradshaw during the team’s last night at URI. Parker suspended Michaels for the game against the Colts, then dealt him to Baltimore two days later.[30]

The Steelers 1964 season was a disappointment as they slid to a 5-9 mark, tied for the second-worst record in the NFL. So when camp started in July 1965 – rookies began reporting in the days leading up to the official start on July 19, while veterans were due by July 25 – there was increasing pressure on Buddy Parker and his staff. Parker declared that he planned to scrimmage the team less frequently this summer than in past years, explaining that “we did very little when I won two titles with the Detroit Lions” and that a less stressful schedule would produce better results.[31] It was another in a line of curious statements by Parker. His Lions of the 1950’s had far more talent (including future Hall of Famer, and current Steelers assistant coach, Bobby Layne) than the 1960’s Steelers; adjusting the practice schedule was not going to solve that problem.

On August 7, the team again held an intra-squad scrimmage for the benefit of the same scholarship funds as the year before, though it was held at Meade Field instead of at an off-site location. Approximately 2,500 fans watched the defense win 28-6. Backup quarterback Bill Nelsen threw a touchdown pass for the offense, while the defense was aided by a pair of field goals by Mike Clark after they intercepted passes by quarterbacks Ed Brown and Tommy Wade.[32]

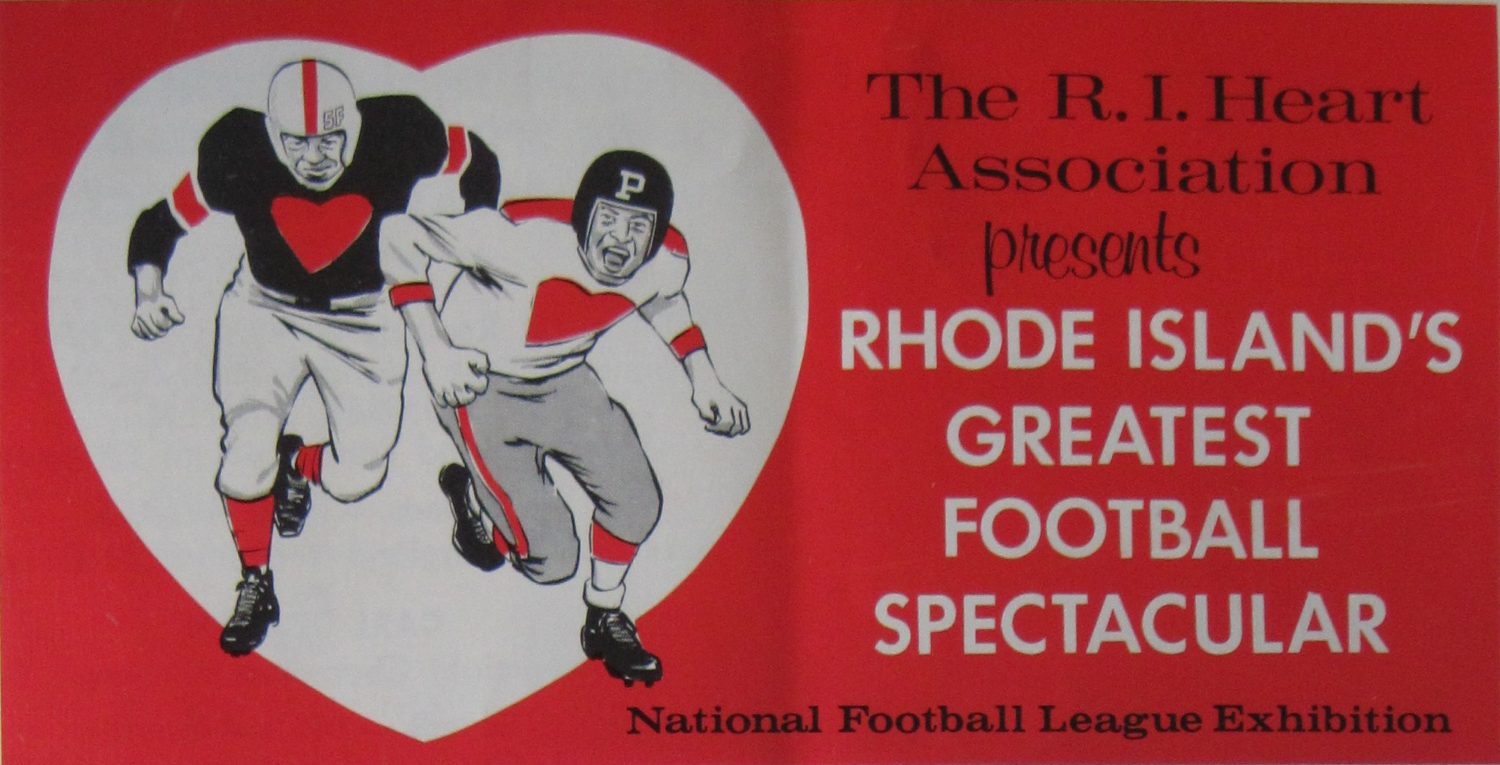

Pittsburgh began its preseason slate with three consecutive losses, then prepared to face the San Francisco 49ers at Brown University Stadium in Providence on Saturday, September 4. Proceeds from the game, the first official NFL contest to be played in Rhode Island in over three decades, would benefit the Rhode Island Heart Association. The 49ers flew to New England after playing the Cardinals to a 17-17 tie in St. Louis on August 27, and planned to practice all week at the University of Connecticut in Storrs; five members of the team spent the last weekend of August at the Newport home of their former teammate John Mellekas.[33]CBS sent a crew of 40 people to televise the game across the country, though it was blacked out locally. Bob Fouts (father of future Hall of Famer Dan) and former 49ers receiver/kicker Gordie Soltau, who worked 49ers games for CBS during the regular season, called the action, along with former college football coach John Sauer, a regular member of the broadcast team for Steelers games on the network.[34] The smallest state in the Union decided to take full advantage of the national exposure, as the Rhode Island Development Council organized a full slate of televised halftime activities intended to showcase the state. The program was scheduled to include a brief speech by Governor John Chafee, a video highlighting the state’s vacation/recreational and industrial facilities, and performances by the East Providence High School band and the Artillery Company of Newport; arrangements had also been made for the reigning Miss Rhode Island, Maureen Manton, to fire one of the latter’s prize cannons that had been cast by Paul Revere in 1798.[35]

Kickoff was at 2pm on a pleasantly warm late summer day, with temperatures in the upper 70’s. The 12,000 fans in attendance paid $5 apiece to watch the Steelers get trounced yet again, 23-9.[36] Bill Nelsen returned to action, against the team doctor’s wishes, despite having suffered a knee injury two weeks earlier against the Giants. Nelsen managed to earn some good reviews for his play despite completing just 5 of 16 passes and fumbling on his own 20 yard line to set up the 49ers first touchdown, a 1-yard run by Dave Kopay in the second quarter that put San Francisco up 10-3. Mike Clark kicked two more field goals to cut the deficit to 10-9, but Tommy Davis added a 39-yard field goal to give the 49ers some breathing room with four minutes left in the third quarter. The Steelers then threatened to take the lead, but Ed Brown was picked off in the end zone on a diving play by cornerback Jerry Mertens. San Francisco proceeded to drive 80 yards for their second touchdown of the afternoon, an 8-yard run by quarterback George Mira, to put the game out of reach.[37]

But by the next day, the details of the game were overshadowed by much bigger news. Buddy Parker had quit as head coach.

The unpredictable Parker had struck again. “This thing has been building up and I actually was ready to quit after the Baltimore game in Atlanta [a 38-10 loss on August 28],” he told reporters late Sunday afternoon upon returning to Pittsburgh. After the loss to the 49ers, Parker and his coaches went to dinner at the exclusive Dunes Club along Narragansett Bay, and Parker told them he was done. Parker then called Dan Rooney to deliver the news that he was walking away from a three-year contract extension that he had received after the 1964 season (supposedly for $80,000 a year). His resignation was officially announced on Sunday, and that afternoon, Parker flew back to Pittsburgh. The front page of Monday’s Pittsburgh Post-Gazette featured a photo of a smiling, obviously relieved Parker after his arrival at the airport. Parker went out of his way to praise Art Rooney – he told Jack Sell of the Post-Gazette: “be sure to put in the paper that Art Rooney is one of the greatest fellows I ever met”[38] – but within a few days, Pat Livingston of the Pittsburgh Press wrote that Rooney had grown tired of Parker; Rooney had ceded control of the roster, training camp locations, and coaching staff to Parker but had not seen results on the field. “Even though he was boss,” Livingston wrote, “there was no way for Rooney to control the actions of the irascible, unpredictable man who worked for him.”[39] Rooney elevated assistant coach Mike Nixon, who had posted an anemic 4-18-2 record in two seasons as the head man in Washington a few years earlier, to replace Parker. The Steelers then broke camp on Wednesday, September 8, and flew back to Pittsburgh to prepare for their final preseason game against the Cleveland Browns.

The Steelers struggled to a 2-12 record in 1965. Nine days after the season ended, Art Rooney fired Mike Nixon; on January 20, 1966, former Pro Bowl guard Bill Austin, who had served as an assistant coach for the Green Bay Packers and Los Angeles Rams, was hired to replace him.[40] The Steelers returned to Rhode Island for training camp, but were planning to leave early for a trip to the West Coast, an early sign that their time at Kingston might be nearing an end. Camp got off to a rocky start. The Steelers had ordered their rookies, quarterbacks, and centers to report on July 10, with the balance of the team to arrive at URI a week later, but a strike by the International Association of Machinists shut down over half of the airlines in the United States beginning on July 9.[41] As a result, several players would fail to arrive on time. Some, like fourth-year center Ray Mansfield, found alternative transportation: Mansfield drove about 2,800 miles from Tri-Cities, Washington to Kingston instead of trying to book a series of flights on regional airlines such as Mohawk, which were not directly affected by the strike.[42]

The following Friday, the Steelers traveled to Fairfield, Connecticut to scrimmage against the Giants at their camp, and the Giants would return the favor by visiting Kingston on August 3.[43] In between, rookie defensive tackle Jim Carter smashed his elbow through the window in his room in Adams Hall while sleepwalking, one of the more bizarre incidents during the Steelers time at URI. “I guess I sleepwalk about every two weeks,” Carter told reporters the next day, “but I never did anything like this before. I remember knocking out the window a little bit, and then I went out the door and down the hall.”[44] His roommate George Fair woke up abruptly when he heard the sound of shattering glass but then went back to sleep; Carter required 12 stitches to repair his damaged elbow.

On Saturday, July 30, the Steelers held their annual intra-squad scholarship fund scrimmage at Meade Field. Rookie quarterback John Stofa, who had relieved starter Bill Nelsen, completed a 65-yard touchdown pass to Roy Jefferson to give the offense a 13-12 victory in front of an “enthusiastic crowd.”[45] On August 11, the Steelers left URI for the summer on a Zantop charter flight from T.F. Green Airport at 12:15pm. After a stopover in Detroit, the team flew on to Portland, Oregon to play two exhibition games against the Minnesota Vikings and San Francisco 49ers.[46]

Meanwhile, a minor league football team that carried the Steelers moniker was struggling to survive at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket. The Rhode Island Steelers were the latest in a line of minor league football teams in the state. After the semipro Providence Steamrollers of the Atlantic Coast Football League (ACFL) folded in 1964, a new ownership group formed the Rhode Island Indians. Dave Gavitt, who would later build a legendary career in college basketball as the head coach at Providence College and founder of the Big East Conference, was the Indians’ general manager, while George Patrick Duffy was the team’s official publicist.[47] Duffy, a sports writer, amateur coach, and broadcaster, handled publicity for a wide array of sporting events in Rhode Island, including the Steelers exhibition game at Brown Stadium in 1965.[48] The Indians were charter members of the Continental League, which was launched in February 1965 with dreams of becoming a third major professional league with former Major League Baseball commissioner Happy Chandler as their commissioner. In July, the Indians scrimmaged against the Steelers at URI. After rookie running back Cannonball Butler made headlines back in Pittsburgh by scoring on an 80-yard touchdown run, the Steelers coaches took the next day off for some deep sea fishing.[49] The Indians started their regular season 3-4, then lost their last seven games. Before the season was even over, there were stories in the Providence Journal that the team would fold, and team president David Haffenreffer officially pulled the plug on November 24.[50]

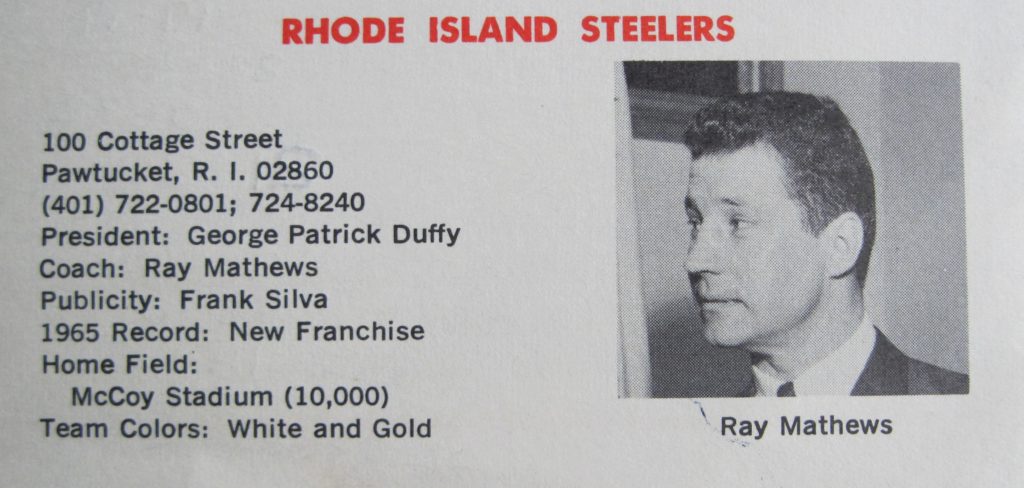

As 1966 began, George Duffy was assembling another group of pro football backers in Rhode Island to replace the Indians, while the Pittsburgh Steelers were looking for a new minor league affiliate after the demise of the Pennsylvania Mustangs of the North American Football League.[51] By March, Duffy had convinced the Steelers to take on his squad as a farm team, and the ACFL officially welcomed the Rhode Island Steelers into their fold.[52] Former Steeler Ray Mathews was named head coach, and he visited several NFL training camps that summer, including the Steelers at URI, looking for talent. The team signed several former Steamrollers and Indians, including quarterback Carl Mobley and former URI defensive back Jim Adams, but struggled on the field. The Steelers lost a pair of exhibition games in August, then began the regular season with two blowout losses on the road by a combined score of 75-14. During their first three home games at McCoy Stadium, the Steelers reportedly averaged just over 2,600 fans.[53]

As the club failed to meet its payroll, players began to leave in droves. “We’ve lost 15 or 16 regulars in the last month,” Mathews told reporters after his Steelers showed up for a game at the Wilmington Clippers on October 2 with just 23 players (and lost 48-7). “We lost our best player to Scranton. He told me he wanted to play but that he wanted also to be paid. Can you blame him? I gave him his release. I didn’t have the heart not to.”[54] Financial troubles were racking the whole league: after starting the season with 10 teams, the New Bedford Sweepers and Atlantic City Senators had already folded by the end of September. Five days after their game against the Clippers, the Rhode Island Steelers followed suit. Their final record was 0-5-1.

From a 1966 Directory and Schedule for the Atlantic Coast Football League (Michael Hamel Collection)

When the Pittsburgh Steelers left URI for Portland in August 1966, Jack Sell wrote in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that the team would not return to Kingston the following summer. The official announcement would not be made until January 18, 1967.[55] Several factors were working against Rhode Island as the Steelers’ training camp site, including declining attendance at practices during the team’s three years at URI. In 2015, Dan Rooney was quoted as saying that the summer weather in Kingston was too cool compared to the climate in Pittsburgh, leaving the team ill-prepared for the start of the regular season.[56] (But a comparison of daily temperatures reported in Providence and Newport against those recorded in Pittsburgh during the summers of 1964-1966 shows an average difference of only a couple of degrees.[57]) There was also the practical matter that Kingston was a long way from Pittsburgh, and, as the airline strike in 1966 had shown, keeping the team in Western Pennsylvania would simplify their travel arrangements. Also, it was Buddy Parker who had chosen URI (supposedly because the weather in the Pittsburgh area had been too hot in earlier summers), and Art Rooney was not enamored of his former head coach. When the team returned from the West Coast in 1966, they held the remainder of their training camp at St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, a school that Art Rooney knew well: his son Art Jr. had graduated from the Catholic institution in 1957 and had lobbied his father to hold training camp there, just as Father Silas had vouched for St. Bonaventure a decade-and-a-half earlier. Since then, the Steelers have continued to hold their training camp at St. Vincent every summer.[58]

[Banner image: From an official game program, Pittsburgh Steelers versus San Francisco 49ers, September 4, 1965 (Michael Hamel Collection)]

Notes

This article was inspired by an article by Shane Donaldson, “When the Steelers Held Training Camp at URI,” published in the Summer 2016 edition of the URI alumni magazine, QuadAngles. The article incorrectly stated that the Steelers trained at URI for only one full summer (1965) and “a week” in 1966 (these statements were apparently borrowed from a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article in 2015 which was vague on these points), but was well-written and an excellent starting point for my own research.

[1] Pat Livingston, “Vagabond Steelers Shift Camp Again,” Pittsburgh Press, March 15, 1964. [2] Cranston Stadium had hosted an exhibition game between the New York Giants and the College All-Stars in September 1939, but that was not an official game between two NFL teams. John Hogrogian, “The 1939 College All-Star Games,” The Coffin Corner, Vol. 25, No. 5, 2003, accessed May 23, 2017, http://profootballresearchers.com/archives/Website_Files/Coffin_Corner/25-05-996.pdf. [3] William Johnson, “After TV Accepted The Call Sunday Was Never The Same,” Sports Illustrated, January 5, 1970. The 1962 contract was for $4.65 million a year. Michael Schiavone, Sports and Labor in the United States (New York: SUNY Press, 2015), 58. The average salary for players increased from $20,000 in 1962 to just $22,000 by 1969. [4] Cameron C. Snyder, “N.F.L. May Give Players $6 Daily Training Allowance,” Baltimore Sun, May 22, 1964. By 1966 the per diem during training camp would increase to $10 a day, see Jack Sell, “It’s Alumni Day at Steeler Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 30, 1966. [5] Steve Mellon, “The ’57 Steelers and their colorful, chain-smoking coach,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 29, 2015. [6] Wire story, “Parker Through as Lion Coach in Sudden Move,” Lawrence Journal-World, August 13, 1957; Pat Livingston, “Parker Takes over Steeler Reins,” Pittsburgh Press, August 28, 1957. [7] Father Silas (O.F.M.) was Athletic Director at St. Bonaventure from 1947 through 1955. See: http://gobonnies.sbu.edu/fan_zone/Images/Hall_of_Fame_Pdf/Rooney-_Silas.pdf, accessed December 28, 2016. Maryann Gogniat Eidemiller, “‘Faith, family, football’ permeates Steelers team, says Benedictine,” Catholic News Service, August 14, 2013, accessed December 28, 2016, http://catholicphilly.com/2013/08/news/sports/faith-family-football-permeates-steelers-team-says-benedictine/. [8] The Steelers training sites during these years were: 1958-1960 California (Pennsylvania) State Teachers College; 1961 Slippery Rock College; 1962-1963 West Liberty College. [9] Pat Livingston, “Vagabond Steelers Shift Camp Again,” Pittsburgh Press, March 15, 1964.[10] Gerald Holland, “The Winning Ways of a Thirty-year Loser,” Sports Illustrated, November 23, 1964. [11] Rob Ruck, Maggie Jones Patterson, and Michael P. Weber. Rooney: A Sporting Life (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 227. [12] Gene Collier, “Rhode Island summers paved way for Steelers training camp in Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 19, 2015. [13] The 1965 URI Yearbook (University of Rhode Island, “The Grist 1965” (1965). Yearbooks. Book 75, p168, http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/yearbooks/75) states that 10,000 fans attended the 1964 homecoming game, and a newspaper article about the 1966 URI homecoming game cited a “record crowd” of 11,331, but the official seating capacity did not reach 8,000 until a new grandstand was built in 1978: Dick Whittier, “Mitchell Powers UVM Over URI Rams, 21-7,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press, October 10, 1966. [14] URI Campus History http://web.uri.edu/about/history-and-timeline/, accessed January 28, 2017. URI dorms did not start to become co-ed until the 1972-73 academic year: University of Rhode Island, “Renaissance 1973” (1973). Yearbooks. Book 67, p67-68, http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/yearbooks/67. A major expansion project in 1966 added several dorms and a new dining hall in the area just east of Meade Field. [15] Jack Sell, “Healthy Steeler Squad Heads for Pre-season Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 20, 1964. Jack Sell, “Steelers Air-Bound to Training Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 21, 1964. [16] Some details about the opening of camp are taken from a 1965 letter sent by the Steelers to their players to notify them about the reporting protocol for camp. One copy of this letter, complete with a hand-written flight itinerary in the margin, was available for purchase on eBay in the winter of 2016. [17] Letter to editor, Fall 2016, QuadAngles; Gene Collier, “Rhode Island summers paved way for Steelers training camp in Latrobe” mentions a National Science Foundation summer institute held on campus in 1965. An item in the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Post on May 14, 1964, mentions an upcoming summer institute to be held on campus from June 22 to July 31, 1964. [18] Jack Sell, “Healthy Steeler Squad Heads For Pre-season Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 20, 1964. [19] Jack Sell, “Two Texans Named Tom Seek Posts with Steelers,” Pittsburgh Press, July 23, 1964. [20] Roy McHugh, “Where There’s Will There’s A Way, But Not Always,” Pittsburgh Press, July 22, 1964. [21] Jack Sell, “Steelers Sign Linebacker,” Pittsburgh Press, August 7, 1964. [22] Bill Reynolds, “Steelers Were Our First Link to NFL,” Providence Journal, August 1, 2010. Movie and entertainment ads in Providence Journal, August 1964. [23] “Steelers Hardly Know There’s a Crowd,” Pittsburgh Press, August 3, 1964. [24] Scrimmage ticket ad, Newport Daily News, August 3, 1964. Steamrollers ticket ad, Providence Journal, August 7, 1964. [25] Jack Sell, “Steelers Hone Up For Eagles Show,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 10, 1964. [26] Joe McHenry, “Nelsen Stars in Steelers Squad Tilt,” Providence Journal, August 9, 1964. Jack Sell, “Steelers Hone Up For Eagles Show,” Pittsburgh Press, August 10, 1964. [27] Jack Sell, “Steelers Cut Five More Aspirants,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 3, 1964. [28] For example: Wire story, “U.S. Plane Crashes in Viet Nam Buildup,” Providence Journal, August 7, 1964, 21. Page 22 featured several photographs of the practicing Steelers above a commentary on Vietnam by James Reston. [29] Jack Sell, “Colts Stomp All Over Steelers, 48 to 17,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 7, 1964. [30] Jimmy Miller, “Steelers Suspend Kicker Lou Michaels,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 3, 1964. Pat Livingston, “Lou Michaels ‘Bout’ Costly,” Pittsburgh Press, September 3, 1964. [31] Wire story, “Steelers Cut Down Camp Drills,” Simpson’s Leader-Times (Kittanning, Pennsylvania), July 31, 1965. [32] “Steelers Defense Wins, 28-6,” Pittsburgh Press, August 8, 1965. [33] Wire Story, “Grid Cards Rally Late For 17-17 Tie,” Kansas City Times, August 28, 1965. “49ers Gridders Weekend Here,” Newport Daily News, August 30, 1965. The five 49ers who reportedly stayed with Mellekas were Billy Kilmer, Dan Colchico, Charlie Krueger, Bruce Bosley, and Carl Rubke. [34] Jack Sell, “Winless Steelers Eye 49ers,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 30, 1965. [35] Joe McHenry, “14,000 Expected for Steelers-49ers Game Today,” Providence Journal, September 4, 1965. “Sports in the News” column, Newport Daily News, August 25, 1965. Newport Artillery web site, accessed September 7, 2016, http://www.newportartillery.org/museum.html. [36] Ticket price from ad in Newport Daily News, July 21, 1965. [37] Joe McHenry, “49ers Pin Steelers in Exhibition, 23-9,” Providence Journal, September 5, 1965. Pat Livingston, “49ers Hand Club Fourth Loss in Row,” Pittsburgh Press, September 5, 1965. Wire story, “49ers Top Steelers, 23 to 9,” Hartford Courant, September 5, 1965. [38] Jack Sell, “Parker Resigns As Steeler Boss,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 6, 1965. [39] Pat Livingston, “Owner Rooney Regains Control of Steelers,” Pittsburgh Press, September 7, 1965. [40] Jack Sell, “Bill Austin New Steeler Coach,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 21, 1966. [41] “Airline Workers Strike in 1966 – and Make History,” July 13, 2015, accessed September 7, 2016, http://www.laborpress.org/national-news/5593-airline-workers-strike-in-1966-and-make-history. [42] Roy McHugh, “Airline Strike Delays Steelers,” Pittsburgh Press, July 11, 1966. [43] “NY Target For Steeler Long Bombs,” Pittsburgh Press, August 4, 1966.

44] Russ Franke, “Carter Cuts Arm in Sleep,” Pittsburgh Press, July 19, 1966.

[45] Jack Sell, “It’s Alumni Day at Steeler Camp,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 30, 1966. Jack Sell, “Stofa Big Hit at QB in Drill,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 1, 1966. [46] Jack Sell, “Steelers Quit Rhode Island for West Coast,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 12, 1966. [47] Charles J. Tiano, “About Those Dartmouth Tix; Check With Mayor’s Office,” The Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, June 7, 1966. Booster Club of the Continental Football League, Inc., accessed January 24, 2017, http://www.boosterclubcfl.com/team_preseason.php?year=1965&team_id=29; Bill Reynolds, “George Patrick Duffy was truly a Rhode Island original,” Providence Journal, May 27, 2015. [48] Ad in Official Game Program, Pittsburgh Steelers vs. San Francisco 49ers, September 4, 1965. Duffy also handled promotions for URI and broadcasted URI basketball and Rhode Island Reds minor league hockey games. [49] Roy McHugh, “Steelers Find Gem-Speedy Canonball <sic>,” Pittsburgh Press, July 25, 1965. “Steeler Rookies Fearful of Ax,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 26, 1965. [50] Wire story, “Rhode Island Indians May Drop Out of Continental Grid League,” Hartford Courant, November 4, 1965. Wire story, “Loss at Gate Causes Indians to Fold,” Hartford Courant, November 25, 1965. The Pro Football Archives, http://www.profootballarchives.com/1965coflri.html . [51] “Charleroi Home For Mustangs,” Pittsburgh Press, February 10, 1965. “Mustangs Season Ends Abruptly, Ahead of Schedule,” The Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), November 15, 1965. [52] “Steelers Take Coast Loop Farm,” Pittsburgh Press, March 2, 1966. Wire story, “R.I. Steelers Get Grid Loop Spot,” Newport Daily News, March 14, 1966. [53] Wire story, “Steelers Withdraw From Football Loop,” Gettysburg Times, October 8, 1966. The Pro Football Archives, http://www.profootballarchives.com/1966acflri.html . [54] Karl Feldner, “591 See Clippers Win 2d,” The (Wilmington, Delaware) News Journal, October 3, 1966. [55] “Steelers Shift Drill Site to St. Vincent,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 19, 1967. [56] Gene Collier, “Rhode Island summers paved way for Steelers training camp in Latrobe,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 19, 2015. [57] Weather reports in the Boston Globe, Newport Daily News, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Pittsburgh Press. [58] Mike Dudurich, “Pittsburgh Steelers Training Camp: 50 Years at Saint Vincent,” accessed January 16, 2017, https://issuu.com/saintvincentcollege/docs/svc_50