In 1914 the city of Providence was convulsed with riots. Starting in late August and lasting into September the streets of the city’s Federal Hill section came alive with violence and social unrest. Ostensibly caused by an increase in the price of macaroni, this predominately Italian immigrant neighborhood was the flash point where Marxists, anarchists and others fanned the frustration that lay beneath the community’s calm veneer. The unrest became known as the Macaroni Riots.[1]

The war in Europe—ignited at Sarajevo in June 1914 by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire—would soon turn into a world war. While it would be another three years before the United States would become an active participant in the conflict, in Providence the effects of the war were felt immediately with a rise in food prices. The rapid and unexplained price rise caused Providence’s Mayor Joseph Gainer to call for an investigation.[2] To conduct the investigation the mayor called upon members of the Rhode Island Retail Grocers’ and Marketmen’s Association to do the investigating. Of course, their findings were to be expected; they declared that they were in no way responsible and that any price raises made by them were necessitated by a corresponding raise which had been made by the wholesalers. One committee member stated, “For years the retail grocer has been made to bear the onus and the stigma of raising prices and he has born the blame patiently.”[3]

Also calling for an investigation was Rhode Island’s Governor Aram Pothier, who asked the state’s Commissioner of Industrial Statistics, George H. Webb, to lead an investigation into the causes of the price increases. Webb’s report noted that “Beans, flour, sugar, olive oil, macaroni, spaghetti and meats have advanced materially by reason of pressure outside of Rhode Island, but it is noticeable that such advances are so varying in amounts that Rhode Island dealers could not have taken any concerted action in the matter.”[4]

Rhode Island’s political leaders could in good conscience feel the problem was outside their jurisdiction and that there was nothing they could do. Perhaps they would have felt differently if there were more registered voters in the Federal Hill immigrant community or if they knew what was to happen next. The Labor Advocate, a socialist newspaper, said it best when it noted, ”What is needed more than an investigation is an awakening on the part of the people—not to the mere fact that they are being robbed; they are only too well aware of that already—but to the fact that there is a way to put an end to it, and that is to put an end to the system of allowing the necessities of life to be controlled by private individuals and sold for profit.”[5] The “people,” prodded on by Marxists and anarchists, were now ready to take action.

The first signs of unrest occurred on Saturday evening August 22. A mass meeting to protest the high cost of food was planned by the Italian Socialist Club. Handbills had been widely circulated several days before the meeting inviting workers to attend. Nearly 2,000 people attended the speakers program at the corner of Dean Street and Atwells Avenue, in the heart of Federal Hill. Also in attendance was a beefed up police detachment of more than seventy patrolmen and officers, including seven officers mounted on horseback drawn from every police station in the city.[6]

At 7:15 p.m. more than a dozen speakers ascended the stand that was specially erected for the protest meeting. The speakers, all members of the Italian Socialist Club, took turns denouncing the high cost of food stuffs, especially pasta, which was a staple of the Italian immigrant’s diet. Coming in for special denouncement was Italian specialty food importer and wholesaler Frank P. Ventrone who ran a large scale operation at 240-244 Atwells Avenue. It was claimed that he had taken several thousand cases of domestic pasta and applied foreign labels to them in order to boost his price. One speaker railed on about the police, but because he spoke in Italian the police were unfazed by his remarks.[7] One of the frustrations within the Italian community was the perceived lack of respect they received at the hands of the police, a force made up mainly of old Yankee stock and Irishmen. These sentiments would soon take center stage in the riots but for the time being the large crowd dispersed quietly after the protest rally ended.

Throughout the ensuing week handbills were circulated calling for a labor rally on Saturday, August 29. The handbills urged readers to attend and plan to “offset” the injustices that they claimed were being inflicted upon the laboring man. Frank Ventrone, having secured one of the handbills and believing that it implied an attack on his store, requested police protection. The rally, similar to the previous week’s rally, consisted of many impassioned speeches by members of the Italian Socialist Club, but this time the speeches had the effect of enraging the crowd of nearly one thousand. When the rally ended the crowd moved down Atwells Avenue, and within a matter of seconds the large plate windows of Ventrone’s store were smashed and the store’s contents scattered onto the street. Numerous other store fronts also fell pretty to the mob’s violence.

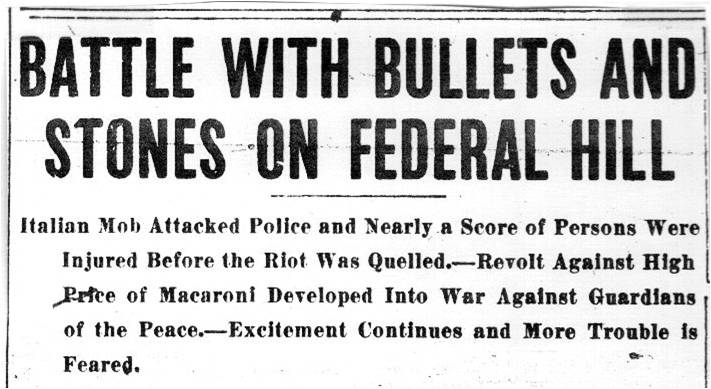

The police on duty were too few to quell the mob and reinforcements were quickly called for. Soon the focus of the mob’s anger shifted from the Ventrone business to the police and an exchange of stones and bullets ensued. As police squads arrived they were met with jeers. With a full complement of police in place the mob was finally dispersed but not before citizens and policemen alike suffered injuries. Despite the dangerous level of violence, only seven arrests were made.[8]

The day following the riot was a Sunday, usually a day of rest observed with church attendance and family gatherings. On this Sunday, however, another riot gripped the city. This one was even more destructive than the one of the night before. Unlike Saturday’s riot, which was largely caused by inflammatory speeches, Sunday’s riot was set off around 3 p.m. by the police arresting in the street an unnamed man. The arrested man was wanted on a warrant for non-support filed by his wife. Believing that it was an arrest as a result of the riots of the night before, people in the streets came to the man’s defense, thus setting off a riot that lasted nearly four hours. The police called for reinforcements and what ensued was a free for all with police firing their weapons into the crowd and some in the crowd returning fire. The center of the battle was at the intersection of Atwells and Arthur Avenues.[9] The official count was eighteen people injured: six policemen, one fireman and eleven citizens—one a fifteen year old boy who was shot in the chest and was thought to be fatally wounded. In reality many more people in the crowd had been wounded, but the injured, fearing arrest if they went to the hospital, sought medical attention elsewhere, either at home or by Italian doctors. Around 7 p.m. the police had taken control of Atwells Avenue and its adjacent streets. For the remainder of the evening an uneasy quiet settled on Federal Hill.[10]

Following two consecutive nights of rioting, Federal Hill was heavily patrolled by the police on Monday evening, August 31,with a force of nearly 200 men. Every street and lane that intersected Atwells Avenue, Federal Hill’s main thoroughfare, was guarded.

On Labor Day a large Socialist Party gathering was called to assemble in Olneyville, a short distance from Federal Hill. As was the case in previous protests, a handbill printed in Italian circulated several days before the scheduled meeting and also appeared in some newspapers. Olneyville was home to the Atlantic Mills and its workforce represented many nationalities. Socialist speakers addressed the crowd in English, French and Italian. Nearly one thousand working men and women attended. The event went off without any disturbances. The police, having learned some recent lessons, had plain-clothes officers detailed within the crowd.

As the crowd dispersed a group of about one hundred young men made their way up Broadway and down Ridge Street to their homes on Federal Hill. As they reached Federal Hill an older man addressed the crowd and urged them to take up sticks and stones. In a short time the crowd turned into an unruly mob and its participants began to throw stones at every building lining Atwells Avenue. No deference was shown as windows of both private dwellings and businesses were shattered. Anticipating the possibility of trouble, extra police were on standby duty at several stations. A call by the plain-clothes officers soon brought out the reserves including twenty-five mounted officers. The mob did not advance three blocks before the mounted force working as a unit moved down the street followed by police offices with nightsticks and weapons drawn. Given the unfortunate number of casualties of the week before, the officers were under strict orders not to shoot. Miraculously nobody was shot and the riot was over in less than thirty minutes. In all twenty-three people were arrested.[11]

Following the Labor Day riot, quiet soon returned to the streets of Providence. Both the Providence Journal and the Providence Tribune stressed that this was a riot of hoodlums and not related to the price of macaroni.[12] In actuality the riots had become as much a revolt against police treatment of residents in Providence’s Little Italy as it was about the cost of macaroni.

[1] See Joseph W. Sullivan, Marxist, Militants & Macaroni – The I.W.W. in Providence’s Little Italy (Kingston, RI: Labor History Society, 2000). [2] “Mayor Says Jump in Food is Beyond His Jurisdiction,” Providence Evening Bulletin, 24 Aug. 1914, p. 1+ and “’Investigating’ Plot to Raise Prices,” Labor Advocate [Providence], 22 Aug. 1914, p. 1. [3] “Local Food Merchants Deny Responsibility,” Evening News [Providence], 21 Aug. 1914, p. 1. [4] “Outsiders Responsible for Increases Here,” Evening News [Providence} 20 Aug. 1914, p. 2. [5] “Intense Suffering Caused by the Rise in Price of Food,” The Labor Advocate [Providence]. 22 Aug. 1914, p. 1. [6] “Italian Workers of Federal Hill Have Big Protest Meeting,” Labor Advocate [Providence], 29 Aug. 1914, p. 1. [7] Ibid. See also “Italians Protest High Food Prices,” Providence Sunday Journal, 23 Aug. 1914, p. 5. [8] “Federal Hill Mob Wrecks 4 Stores,” Providence Sunday Journal, 30 Aug. 1914, p. 1+. [9] “Many Wounded By Police Bullet’s On Federal Hill,” Labor Advocate [Providence], 5 Sept. 1914, p. 1. [10] Ibid. See also “18 Hurt In Riot On Federal Hill,” Providence Journal, 31 Aug. 1914, extra, p. 1+ and“Battle With Bullets And Stones On Federal Hill,” Evening Tribune [Providence], 31 Aug. 1914, extra, p.1+. [11] Sullivan, Marxist, Militants& Macaroni, 77-84. [12] “23 Arrest Mark Federal Hill Riot,” Providence Journal, 8 Sept. 1914, p. 1+ and “Another Federal Hill Riot is Quickly Suppressed by Police,” Providence Tribune, 8 Sept. 1914, extra, p. 2.Additional Sources

[Cover image credit: Evening Tribune [Providence], 31 Aug. 1914. Russell J. DeSimone Collection.]Buhle, Paul. “Italian-American Radicals and Labor in Rhode Island, 1905 – 1930.” Labor and Community Militance in Rhode Island: Radical History Review. New York, NY: Radical Historians’ Organization, Spring, 1978.

DeSimone, Russell J. “Providence’s ‘Macaroni Riots’ of 1914.” Italian Americana. Providence, RI: University of Rhode Island, Feinstein College of Continuing Education, Summer, 2014.

Luconi, Stefano. The Italian-American Vote in Providence, 1916-1948. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004.

Smith, Judith E. Family Connections. A History of Italian & Jewish Immigrant Lives in Providence Rhode Island 1900–1940. Albany, NY: State University Press of New York, 1985.

Sterne, Evelyn S. Ballots and Bibles. Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Sullivan, Joseph W. Marxist, Militants & Macaroni: The I.W.W. in Providence’s Little Italy. Kingston, RI: Rhode Island Labor History Society, 2000.

Vecoli, Rudolph J. (ed.). Italian American Radicalism. Old World Origins and New World Developments. Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference of the American Italian Historical Association, Boston 11 November 1972. New York, NY: American Italian Historical Association, [1973].