When traveling through rural Rhode Island one cannot help but notice the numerous stone walls, many of them inexplicably running through wooded areas with no signs of habitation. The stones to make up these walls are the result of the ice age. As farmers tilled their fields the stones would be brought to the surface and set aside only to be used in the construction of stone walls when the farmer’s other chores were completed. Fieldstones would find many other uses, one of which was in the construction of animal pounds throughout the state’s towns. Some of these pounds still exist and can be seen by the observant traveler alongside the road.

The purpose of a town animal pound was simple – to corral stray farm animals until they could be retrieved by their owners. Rhode Island was mainly an agricultural place in its early colonial years and farm animals grazed in open pastures. Often these animals would stray into town streets and other places where they were less welcome, one might say stray animals could be a nuisance. As such it was the job of the town’s pound keeper to lead the stray animals into the town pound until their owners came to claim them. While extent town animal pounds in Rhode Island are all constructed of fieldstones there was a time when some of these enclosures were constructed of wood, probably logs from felled trees. It is a safe bet to say that most towns had an animal pound at one time. One clue is that some towns have a road named Pound Street or Road even though today there is no evidence of an animal pound having been there, examples include Pound Hill Road in North Smithfield and Pound Road in Westerly. As noted by Walter Nebiker in his history of North Smithfield “A site for a pound in the northern part of the town was chosen in present Union Village, near what is now Pound Hill Road, and in 1738 a pound was built near John Sayles’ residence.”[1] No pound is located there now, such is the price of progress that we occasionally lose sight of our past.

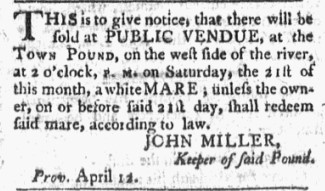

A town’s pound keeper was an elected or appointed position and of necessity a freeman of the town. The keeper was responsible for capturing stray livestock (usually cows, horses, sheep and swine), impounding, feeding and watering them. Other duties included locating the stray’s owner and if not located placing the animal up for public auction. No doubt stray animals were a problem, as noted by Providence’s town clerk Theodore Foster in a public notice on April 18, 1781, “Whereas pernisous Consequences arise from the great Number of Cows which now run at large in the Common, in this Town, some of which are very ungovernable, breaking through lawful Fence into the Inclosures of the Inhabitants and it is absolutely necessary that Measures be adopted for preventing the Mischief arising from braschy and ungovernable Cows:….”[2] One of the outcomes of this Providence notice was to form a committee of three men who would determine which cows shall not be permitted to go on the common. Town inhabitants would need a permit for them to have their cows graze on the common and even then only one cow at a time was permitted per inhabitant. By 1853 the General Assembly amended an act titled “An Act to prevent certain animals from going at large.” This amendment authorized each town to appoint one or more Field Drivers who were empowered, similar to freeholders and qualified voters, to impound animals. The new amendment required keepers of the town pound to receive, keep and feed any strayed animal and to dispose of said animals as if it had been impounded by a freehold or qualified voter. Usually, the stray animal was reclaimed by its owner after paying a small fine and reimbursing the keeper for the cost of feed and care. However, if an animal was not reclaimed the pound keeper could dispose of the stray by other means. Occasionally an ad would appear in the local newspaper announcing the owner to appear and claim his animal else the stray would be sold at public auction. See Figure 1. What exactly was the cost of having an animal impounded varied over time and by the kind of animal it was; some insight into the cost can be found in a noticed published in a Providence newspaper in 1790 where impounded sheep cost three pence per sheep and two shillings per horse. Of course, this did not include the cost of feeding and caring for the animal which was to be paid to the pound keeper. In the same newspaper notice Providence also required that after forty-eight hours the pound keeper was required to place three public notices in the towns of Providence, North Providence, and Johnston. If the animal was not claimed within twenty days the animal was to be sold at a public venue and the proceeds of the sale were to go into the town treasury.[3]

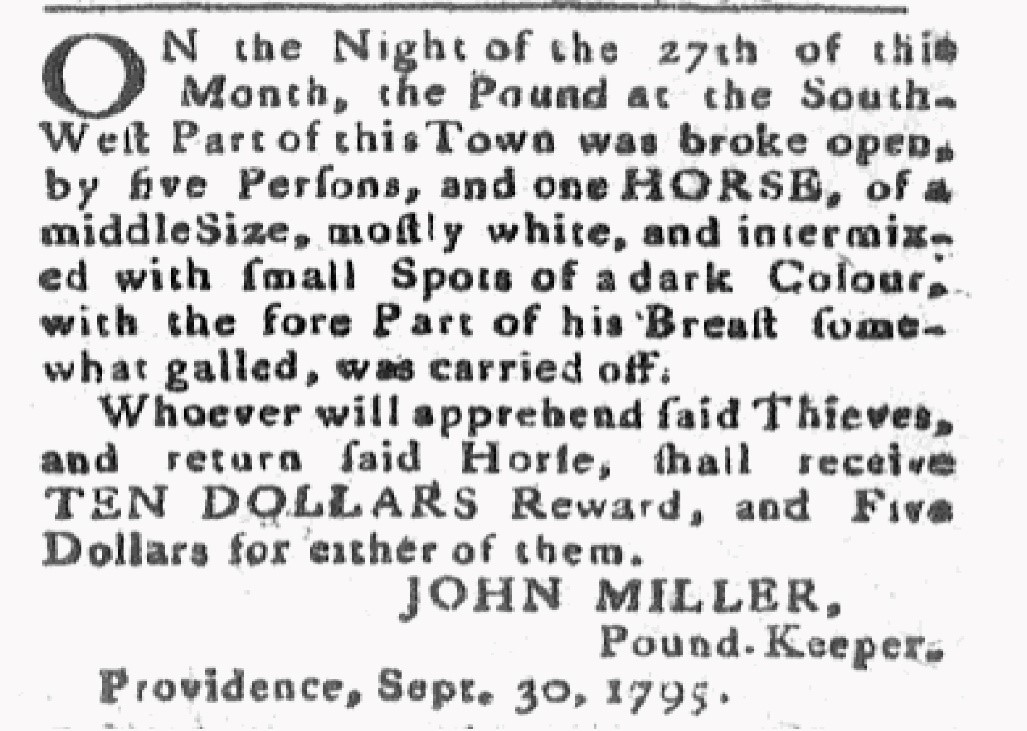

The lot of a pound keeper was not just tending to the strays or as just noted placing an animal out to auction but occasionally he was responsible for tracking down any animals that were taken from the pound without permission. John Miller, the pound keeper of Providence, had such a situation in September 1795 when a horse was taken from the south-west pound in the town. Miller was required to place an ad in the local newspapers offering a reward for the capture of the thieves or the return of the horse. See Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Reward for the apprehension of the thieves who took a horse from the Providence pound. United States Chronicle October 1, 1795

Identifying the owner of a stay was somewhat aided by identifying ear marks placed on the animal. One clue can be found in the early colonial records of Portsmouth where a lengthy list of the various markings on cattle are described. These usually were described as cuts, nicks, slits or crops into the animal’s ear – presumably this was the method before branding with hot irons or ear tags came into use. One sample entry reads “The Ear marke of the cattel of William Sanford is A fforegad on ye left Ear and A halfpenny under the Right Ear.”[4]

Exactly when a town commissioned a pound to be constructed varies by town, but evidence shows that within a short time of being incorporated a town would call for a pound to be built. The four first towns in colonial Rhode Island are Providence (1636), Portsmouth (!638), Newport (1639), and Warwick (1642) all had pounds. Newport was without doubt the largest and most prosperous town of the colony in the early years, even after the American Revolution when the town was much depleted of its riches and its population, it still maintained two pounds. The Newport Mercury reported on June 18, 1808 in the town’s elections that William Stall was elected as pound keeper for the North Pound and Joseph Willbour for the keeper of the South Pound. Just seven years after its founding the town of Warwick at a town meeting in 1649 ordered “That Mr. Smith and Mr. Warner shall procure a workman or workmen to build a prison house & pound by the lott that was layd out to Peter Buzicot….” [5] The specification called for it to be built 20 feet in length and 12 foot wide. However, less than 20 years later at a June 1666 town meeting it was voted “That a pound Six foot & a halfe bye be made at ye Charge of the Towne….” [6] Edmund Calverley was appointed keeper and received a fee of four pence for every horse pounded but only two pence for all other creatures. Unfortunately, only Warwick of the first four towns still has a pound standing.

Rather quaintly one town in nearby Massachusetts specified for its pound to be “horse high, bull strong, and pig tight”. This specification does give us an idea of the type of animals the pound was intended to hold. Rhode Island pounds seen to be constructed anywhere from five to six feet in height and walls at their base of four to five feet in width but tapering to about three feet at the top.

We are fortunate in Rhode Island to have so many of these animal pounds still standing, after all stones don’t decay and unless dismantled by people they will stand for centuries. I have located eleven animal pounds sites throughout the state but possibly there exists a few I don’t know about. I say “pound sites” for two of them can hardly be recognized as anything resembling a pound. I first became aware of the existence of two of them many years ago when I read Abandoned New England by William F. Robinson in 1976. Shortly thereafter I traveled to Glocester to inspect the animal pound just outside the village of Chepachet on Route 102. Soon after I located the pound in Exeter that is also on Route 102, although many miles from the one in Chepachet. Now, nearly fifty years later, I happened to be driving on South Killingly Road near Foster Center when I noticed an animal pound aside the road – almost hiding in plain sight. My interest was now piqued, so I set out to locate other animal pounds in the state. To a large degree I relied on the numerous publications of the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission (RIP&HC) to determine if a town had an animal pound still standing. I was not disappointed; these publications lists pounds in nine towns only omitting to mention the one in Warwick. My mission was now clear I would travel to each of the towns and visually inspect the pounds and take a photograph of each.

Here is what I found including the three I already mentioned:

Charlestown – The remains of this town’s 18th century animal pound can be located on Old Mill Road. It is in poor condition and might not be recognizable to the casual observer as an animal pound. Of all the remaining town pounds in Rhode Island this one and another in Cumberland are in such sad condition that they can barely be considered for inclusion in this essay.

Cumberland – The RIH&PC reported in its 1998 revised publication for Cumberland that the town pound, established in 1750, was located on Mendon Road at the intersection of Pound Road and “It has been abandoned for some time and today is indicated only by parts of the now collapsed stone walls. Two granite entry post, visible in 1990, have been removed or destroyed.” I visited this site twice and found no evidence of the town pound just the remnants of what might be its collapsed stone walls. An old picture published in the RIH&PPC provides the reader with some idea of what the pound once looked like. The loss of this pound is a sad reminder of the expansion of the population into what was once a rural area. A minor consolation for this loss is today near the corner of Mendon and Pound roads stands the Cumberland Animal Hospital at 6 Pound Road.

Exeter – This town’s animal pound is located on Victory Highway (Rt. 102). The right wall from the entrance to this pound is mostly missing (see Figure 5) as is the front gate. Two large trees now grow inside the compound. There is no accompanying signage.

Foster – The pound is located on South Killingly Road near Foster Center. Built in 1845, the pound has the added feature of having a small brook flowing through it thereby facilitating drinking water for livestock. It is approximately forty-eight feet square with walls five feet high and two and a half feet wide. The lintel remains as does a wooden gate. A small, weathered sign notes it is the town’s animal pound. See Figure 6.

Glocester – The town pound was first built in 1749 and consists of fieldstone walls of about six feet in height and capped with flat fieldstones. Its stone lentil sets off the opening that has a metal gate, probably not original, however. According to town records the land was conveyed to the town by Isaiah Inman in 1746. Appropriately enough the pound is located on the Victory Highway (Route 102) at the intersection of Pound Road. In the mid-18th century, the town council approved a fine for stray cattle at 20 shillings a head. Cattle not claimed after ten days were subject to be sold at public auction. This pound ceased to be used in the late 19th century. It is one of the better preserved of all pounds in Rhode Island. While on a busy road not conducive to foot traffic, however, some signage would add to the pound’s significance.

Hopkinton – Hopkinton is the only Rhode Island town that can boast of having two extent historic animal pounds. One located on Chace Hill Road was constructed ca. 1865 and the other is located on Skunk Hill Road. The Chace Hill Road pound located in the South Hopkinton area is in good condition without any vegetation overgrowth. Situated equally distant between the villages of Ashaway and Bradford it presumably served both areas. This pound has a 20th century wooden gate and signage on the gate denotes the date of 1865.

The town’s other pound is on Skunk Hill Road in Hope Valley, it is in poor condition with a half dozen trees and various forms of other vegetation growing within its four walls. This pound also has a good amount of ground water around it further limiting the ability to explore it. Cole’s History of Washington and Kent Counties noted that Hopkinton was incorporated on March 19, 1757 from land taken from Westerly. Several weeks later at the town’s meeting on April 4th it was voted that Benjamin Barber be the town’s pound keeper; presumably pound keepers were voted into office annually thereafter well into the 19th century.

Jamestown – In 1698 Nicholas Carr was instructed to build an animal pound and the following year Jamestown had its first pound, but it wasn’t to be the town’s last. Other pounds were constructed, also of wood, in succession to replace earlier ones that fell into disrepair. In 1770 the town council approved a new pound to be construct of field stone. Over time this pound required repairs and by 1860, it like its predecessors, needed to be replaced. Today’s surviving pound, located on North Road, was built of stone in 1861 by Amaziah K. Gorton using the stones from the 1770 pound. It measures 40 feet by forty feet and is the town’s sixth pound. A very useful informative sign provides much information on the history of animal pounds in Jamestown. This pound was restored in 2015 and is without doubt in the best state of repair of all eleven remaining pounds in Rhode Island.

Figure 10 – Jamestown’s animal pound on North Road is in fine condition and has signage (Russell J. DeSimone)

Richmond – Built in 1846 this town’s pound is located on Carolina-Noose Neck Road near the intersection of Route 138. The pound measures thirty foot square and its fieldstone walls are an impressive six feet tall. This is the largest pound of the surviving pounds in Rhode Island. While it is a massive structure it is cluttered with a number of felled tree limbs. The entrance to the pound is to the left of the side wall that faces the street. There is no gate. Its first pound keeper was John H. Lillibridge and was built on land purchased from the Lillibridge family for two dollars.[7]

An earlier pound was built in Richmond shortly after the town was incorporated. Originally Richmond was part of the town of Charlestown but in 1747 the new town was incorporated. At a town meeting in August 1750 Richard Bailey was selected as pound keeper and tasked to build a pound forty feet square however the following year John Webb was selected town pound keeper and Webb was instructed to build a town pound on his land near his house. Webb was paid by the town thirty-five pounds and seventeen shillings. The location of this earlier pound is unknown as it was reported in 1976 “Members of the Richmond Historical Society, though searching ardently during the past year, but have been unable to locate this pound.”[8]

South Kingstown – This 18th century animal pound is located on South Road, just south of the intersection of Curtis Corner Road. It is in remarkably good shape with a rickety wooden gate; however, several large trees are growing within its walls and there is no signage. See Figure 12.

Warwick – This town’s animal pound is located on Cowesett Road and is back a distance from the roadside. It was built in 1742 by David Greene although it is believed an earlier pound made of wood stood on this site. The structure is about five foot tall. During a 20th century restoration, a wooden gate was placed at the pound’s entrance. Interestingly from the informational sign near the road it appears the pound was in use well into the 20th century. Amasa Sprague, the town’s last keeper, was appointed in 1926. See Figure 13.

These remaining animal pounds, while just a small number in comparison to the number of animal pounds that once existed, stand as testimony to Rhode Island’s agrarian roots. Excluding the pounds in Jamestown and Warwick all the other extent pounds have no significant signage to call attention to them; this I think could easily be remedied by action on the part of local town historical preservation societies and installed by the town’s department of public works. It would not cost much to provide signage and it would make it easier to locate them when driving past in a car. So the next time you are driving down the road be on the lookout for these relics of Rhode Island’s past. Maybe even pull over and inspect them up close. I guarantee it will transport you back in time.

[1] Walter Nebiker, The History of North Smithfield, 23.

[2] The Providence Gazette and Country Journal, May 12, 1781.

[3] The Providence Gazette and Country Journal, June 19, 1790.

[4] Howard Chapin, The Early Records of the Town of Portsmouth, 261-295.

[5] Howard Chapin, The Early Records of the Town of Warwick, 49.

[6] Chapin, 166.

[7] Drftways into the Past, The Richmond Historical Society, 113-114.

[8] Driftways into the Past, 66