Wooden ribs are found barely exposed from the sand on a beach at low tide in the Patagonia region of Argentina. With the combination of marine archeology, historical research and scientifically dating of trees, scientists have recently concluded that the remains are likely those of the Rhode Island whaling ship Dolphin, which had departed from Warren in 1858 and later wrecked off the coast of Argentina in 1859. This extraordinary confluence of expertise in different disciplines has led to this remarkable discovery.

The discovery of is also a reminder that Rhode Island sent out a substantial number of whaling ships in the 18th and 19th centuries, and that its leading whaling port was Warren. This article will discuss the recent discovery and identification. Next week’s article will focus on Rhode Island’s whaling past, which was dominated by Warren.

The story started in 2004, when shifting sand revealed the partial remains of a wooden boat on a barren beach off Puerto Madryn, today a city in Bahia Nueva (New Bay in English), on the coast of Patagonia in Argentina. Most of the structure above the keel has disappeared; only a section of the ship about 80 feet long still exists. In 2006, marine archeologists from Argentina began examining the remains of the wreck.

The marine archeologists knew that it was common for American whaling ships to attempt to sail around Cape Horn, the treacherous southern tip of South America. Whaling ships had killed so many whales off the coast of North America and in the Atlantic Ocean that the whale populations there plummeted. Whalers in the 19th century had to sail around Cape Horn to reach the rich whale hunting grounds in the vast Pacific Ocean. Some of the whalers did not make it.

Whales were an important commercial product in the 18th and 19th centuries. The main product was oil used to light lamps and as an industrial lubricant. Other products included wax for candles and soap, and whale baleen used for small household items. The demand for whale oil began to slacken in the mid-19th century as petroleum oil from underground wells in Pennsylvania began to supplant it and eventually the demand for whale oil disappeared entirely.

The remains of two iron cauldrons and bricks found next to the ship indicated that the ship was a whaler, which would have used these items to boil down blubber on the ship. Next, historical research indicated that the location of the wreck could mean it was the whaling ship Dolphin from Warren, Rhode Island.

Walter Nebiker, who worked for the Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission and was a local Warren historian, provided important clues. He wrote a manuscript on the history of whaling in Warren, but he passed away in 2013, before the manuscript could be published. In the manuscript, Nebiker writes that the Dolphin was constructed between August and October of 1850, towards the end of the whaling industry’s peak. Made of oak, pine and other woods, weighing 325 tons, and measuring in at about 110 feet long, the Dolphin launched from Warren on November 16, 1850. Described by Nebiker as “probably the fastest square-rigger of all time,” the bark traveled the globe in the next few years scouring the Indian and Atlantic oceans for whales, including sailing to the Azores and, after sailing around the Horn of Africa, to the Seychelles, Zanzibar and Australia.

The Dolphin, under the command of Captain Norrie, departed on its ill-fated voyage from Warren on October 2, 1858. The first mission was to be on the lookout for whales on the way to sailing around the dreaded Cape Horn south of Argentina and Chile. The vessel never reached Cape Horn. A letter to the owners from Captain Norrie said his vessel had been destroyed a few months later and that it now “lay upon the rocks in the southwestern part of New Bay.” This last reference most probably is a reference to Golfo Nueva, where Puerto Madryn is located. It was reportedly one of the few natural harbors in Patagonia where whalers were known to put in for protection from storms. In 1859, only indigenous people resided in the area.

An Argentine historical document also revealed that an Argentine mariner reported rescuing forty-two crew members of the Dolphin and took them to Carmen de Patagones. From there, it is thought the Rhode Islanders made their way home.

This information was promising, but other wrecks were known to have occurred in the bay.

In 2012, Ted Hayes, then of the East BayRI online newspaper, reported that marine archeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology in Argentina believed they had found the remains of the wreck of the Dolphin. This announcement put pressure on the archeologists to try to get more certainty as to their tentative conclusions.

Finally, in 2019, the Argentine archeologists turned to Ignacio Mundo of Argentina’s Laboratory of Dendrochronology and Environmental History. Dendrochronology is a relatively new field studying tree rings. Dendrochronology can date old wooden structures by measuring the annual growth rings in the ship’s wood. The science can also help researchers determine where the tree grew, since climates vary in different regions and produce differences in growth rings.

Mundo turned to Ed Cook, one of the world’s experts in dendrochronology and founder of the Lamont-Doherty Tree Ring Lab of Columbia University in New York City. Amazingly, Cook has access to a database of 30,000 trees going back more than 2,000 years. Computer analysis allows unknown timber samples of tree rings to be compared to known samples of tree rings with a high degree of accuracy.

Dendrochronologists, after testing the ribs of the ship’s remains, determined that they were made of white oak, probably from the northeastern United States. According to the researchers, the oaks likely came from Massachusetts. One marker was that Massachusetts had low tree growth periods from the 1680s to the 1690s, and in the 1810s. The most “striking evidence” they found that that the outermost rings on the oaks had been cut in 1849, coinciding with the ship’s construction in 1850. (At this time, trees were often felled in winter months and then were left to season a year or so before being used.) Other wood used for the hull was determined to be yellow pine that was from after 1810.

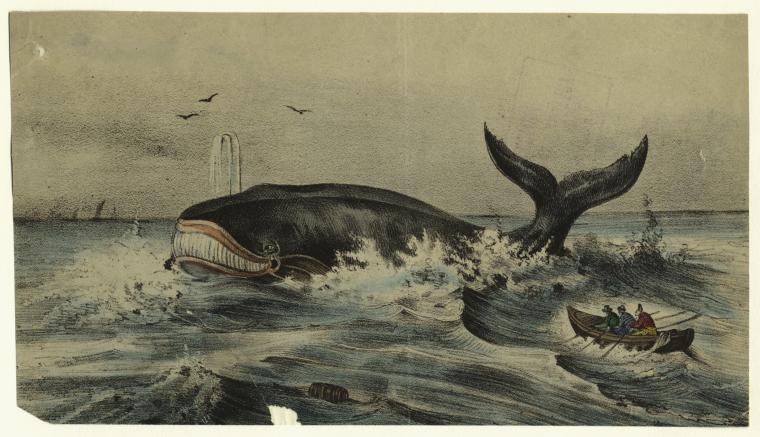

An unidentified whaling vessel from the mid-1800s (New Bedford Whaling Collection, Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Mundo and Cook, with others, co-authored an article of their findings in the scholarly journal Dendrochronologia in its August 2022 edition. The link to the article can be found at the end of this article under Sources.

Mundo was quoted in an article on the website for the Columbia Climate School at Columbia University as saying, “I cannot say with a hundred percent certainty, but analysis of the tree rings indicates it is very likely that this is the ship,” that is, the whaler Dolphin from Warren.

According to a contemporary newspaper account, “the Dolphin proved a first rate sea boat and remarkably fast sailor, and had outsailed every vessel it had fallen in with.” On its maiden voyage, the whaler departed Warren on November 16, 1850, and made its way for the Indian Ocean. Over the next two and a half years, the bark sailed thousands of miles, including sailing from Madagascar to the Seychelles, in a desperate search for whales.

Maritime historian Joan Druett, in an article on the Dolphin she published on her website in 2012, told of more of the history of the whaler, probably primarily using as a source Nebiker’s unpublished manuscript. She wrote:

“. . . . the Dolphin started her maiden voyage on November 15 that same year, and returned almost exactly three years later, on September 5, 1853.

To make money, a whaler had to return with a cargo of about 3,000 barrels (about 100,000 gallons) of oil, having killed about fifty whales. The master of the Dolphin, Captain Charles R. Cutler, reported just 260 barrels.

It had been a very unlucky voyage. In the logbook (now held by the New Bedford Whaling Museum) he wrote on June 8,1852: “We are getting no oil. God help us and send us many whales so that we may put once more to a Christian land again to my dear wife and family.”

Nevertheless, he was given the command again, departing from Warren on May 17, 1854. As before, he steered for the Indian Ocean. Part way through the voyage, he left the ship, probably because of illness. The mate, who was left in charge, died. The vessel finally returned on January 17, 1858, but at least the report — 824 barrels — had improved.

Still, however, it was a losing voyage. The owners in Warren were making no money.

On her third voyage, Captain Samuel Norie was in command. She sailed on September 30, 1858, and within months was reported lost on the coast of Patagonia.”

I did some of my own research in contemporary newspapers and came up with the following.

A newspaper report indicated that the bark Dolphin, commanded by Cutler, when it arrived back at Warren on January 17, 1857 from the Indian Ocean, had on board 800 barrels of sperm product and 40 barrels of whale oil, and that it had earlier sent back to Warren 135 barrels of sperm oil. In addition, three of the ship’s sailors were killed when a small boat capsized that was sent to obtain firewood. This information was in the January 20, 1958 edition of the New York Herald.

Whaling bark Wanderer wrecked on the rocks at Cuttyhunk Island (New Bedford Whaling Collection, Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

The remaining newspaper accounts I found concern reports of the wreck of the Dolphin and the fate of its crew. I found, in the December 21, 1859 edition of the Boston Daily Advertiser Marine Journal, the following squib: “Accounts from Montevideo [in Uraguay] to Oct. 8, states that news has reached that port that the whaling barque Dolphin, of Warren, RI, has been lost on the Coast of Patagonia.” The same newspaper in the next day’s edition wrote: “Whaling Bark Dolphin, Norrie, of Warren, RI, lost on the Coast of Patagonia, sailed from Warren Sept. 30, 1858, for Hurds Islands, and was last reported Jan. 15, 1859, off River Galligus, clean.” This last report was repeated in the December 23, 1859 edition of the Telegraph Marine Report in the New York Herald. The reports likely came from sailors on board ships that had come across the survivors of the Dolphin.

The destination, Hurds Islands, was in the southern Indian Ocean. The river referred to was the Gallegos River in the Argentine province of Santa Cruz, which is about 642 miles south of Puerto Madryn.

I found more information that referred to a letter from Captain Norrie. The Telegraph Marine Report in the New York Herald, for January 15, 1860, had this squib:

“WHALING BARK DOLPHIN. R B Johnson, of Warren, RI, has received a letter from Capt. Norrie, late of bark Dolphin, of Warren, before reported lost, dated at Rio Negro, Brazil, Oct. 14, 1859, which states that the vessel was sold at auction Sept. 5, with everything belonging to her as she lay upon the rocks in the SW part of New Bay, Coast of Patagonia, for $225. Nineteen of the men left New Bay in two whale boats, and after much suffering and privation succeeded in reaching Rio Negro. It is supposed that she had on board at the time of her loss about 300 bbls [barrels] of oil. The D [Dolphin] was a fine vessel of 325 tons, built at Warren, RI, in 1850, and was insured for $24,000 in New York (not Boston, as previously stated.)”

The fact that the Dolphin was sold at auction for only $225 indicates that there was not much to sell. Perhaps some sails, rigging and equipment were sold. R. B. Johnson was the managing owner of the Dolphin.

I am not sure where Rio Negro, Brazil, was, but is was likely at least about 1,600 miles from Puerto Madryn in Argentina. It must have been an incredibly arduous and painful journey. At the time in the area of what is now Puerto Madryn, only indigenous people lived there. The Rhode Islanders needed to get back to a port where they could take a sailing vessel back home.

The squib indicates that the Dolphin was finding some whales even before it went around Cape Horn. The report that it was seen last at the Gallegos River is interesting, since that is well south of Puerto Madryn. Presumably, Captain Norrie was finding whaling along the coast of Argentina successful, at least until his ship became grounded in New Bay.

Prior to the disastrous Dolphin voyage, Captain Norrie had commanded three whaling voyages out of New London, Connecticut, from 1849 to 1856. After he returned to New England, he commanded two more whaling ships out of New London, one in 1869 and the other in 1871.

Of course, most Rhode Island stories about shipwrecks and questions about their origin involve wooden ships that sunk in Narragansett Bay. It would certainly be interesting to use dendrochronology to measure the tree rings on certain wrecks in the bay, in particular, the remains of what may be the former bark Endeavour, the ship Captain James Cook commanded in his famous voyage to Australia and New Zealand.

[Next week’s article: The Rhode Island Whaling Industry is Dominated by Warren]

Sources:

Joan Druett, “Wreck of American Whaling Bark found in Argentina,” May 31, 2012, at World of the Written Word: Wreck of American whaling bark found in Argentina (joan-druett.blogspot.com)

Ted Hayes, “Warren Whaling Ship Wreck found in Argentina? Archeologists aren’t sure but suspect wreck could be Dolphin, built here in 1850,” May 29, 2012, The Ocean Update, at https://whalesandmarinefauna.wordpress.com/2012/05/30/warren-whaling-ship-wreck-found-in-argentina/

Kevin Krajick, “Scientists Say a Shipwreck Off Patagonia Is a Long-Lost 1850s Rhode Island Whaler, Tree Rings Help Identify Remains Some 10,000 Miles From Home,” posted Aug. 24, 2022, at https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2022/08/24/scientists-say-a-shipwreck-off-patagonia-is-a-long-lost-1850s-rhode-island-whaler/

Kaitlyn Murray, “Rhode Island Whaling Ship Identified Off Patagonia After Nearly Two Centuries Lost at Sea, Scientists used tree rings found in the wood of the remains to help trace its origins back to Warren, Rhode Island,” Rhode Island Monthly, Aug. 25, 2022, at https://www.rimonthly.com/rhode-island-whaling-ship-identified-off-patagonia-after-two-centuries-lost-at-sea/

Jack Perry, “Tree rings helped identify a 160-year old wreck off Argentina as lost Rhode Island whaler,” Providence Journal, Aug. 30, 2022, at https://www.providencejournal.com/story/news/local/2022/08/30/warren-ri-whaling-ship-southern-argentina/7903002001/

April Rubin, “How Tree Rings Helped Identify a Rhode Island Whaler Lost at Sea,” New York Times, Sept. 7, 2022, at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/07/science/shipwreck-patagonia-rhode-island-whaler.html

The scholarly study can be purchased and accessed here:

I.A. Mundo, C. Murray, M. Gross, M.P. Rao, E.R. Cook, and R. Villalba, “Dendrochronological dating and provenance determination of a 19th century whaler in Patagonia (Puerto Madryn, Argentina),” vol. 74, Dendrochronologia (Aug. 2022), at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1125786522000601?dgcid=coauthor

For Captain’s Norrie’s voyages, see Federal Writers’ Project, Whaling Masters, Voyages, 1731-1925 (New Bedford, MA: Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1938), 209-10.