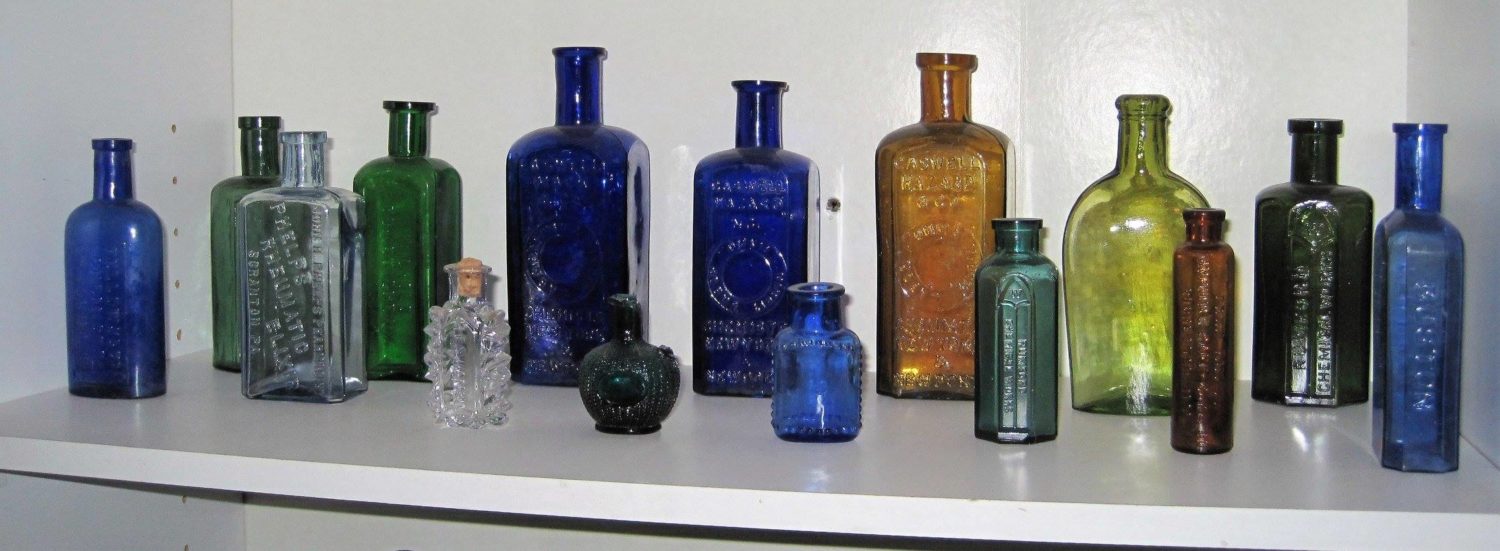

My fascination with antique glass bottles began when I was around ten years old. I was visiting a neighbor’s house that was built near an old cellar hole. I was greeted with a menagerie of vintage relics, from old cars, farm equipment, to even an old safe. I noticed an old bottle sticking out of the ground, and upon retrieving it, I was hooked.

As my collection grew, I figured it might be prudent to narrow down my area of interest to the small state of Rhode Island. It seemed like a good way to keep my collection to a manageable size at the time, but now here I am with over 3,500 different Rhode Island bottles! Who knew that Rhode Island businesses from the 1850s to the 1950s (the period of my collection) would be so prolific?

At one point I started to become curious about the history of all these bottles. Accordingly, I started taking trips for research at local libraries and the Rhode Island Historical Society.

Among my favorite bottles are those that once held local patent medicines. These medicines were concoctions created almost exclusively by people who had no experience in science or medicine whatsoever. Most often the main ingredient was alcohol or a potent narcotic that would undoubtedly make the user feel better before further crippling them. If the creation had any kind of success, the business owner would often register the tradename of it with the United States Patent Office to prevent copycats. The age of quackery largely came to an end around 1906 when Congress enacted the Pure Food and Drugs Act, which required that the bottle’s ingredients be listed on every label.

Below are a couple of my personal favorites from my collection of medicine bottles (all photographs of bottles were made by the author of bottles in the author’s collection).

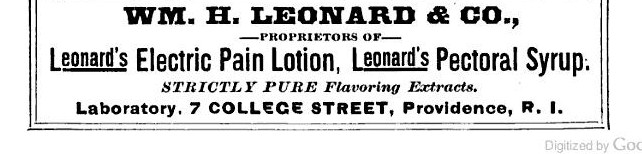

1. Leonard’s Electric Pain Lotion

William H. Leonard moved to Providence after fighting in the Civil War. He obtained a peddler’s license, which was made easier because of his status as a disabled veteran. By the early 1870s he was advertising quack medicines including Leonard’s Pectoral Syrup. By 1889 he was advertising Leonard’s Electric Pain Lotion. The location of his “laboratory” was 7 College Street in Providence. The idea of electricity in a medicine bottle did not sound appealing to me, but perhaps it did with some of his customers. What this medicine claimed to treat I did not discover. This bottle was unknown to collectors until I dug up the only known example of one at a farm dump in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

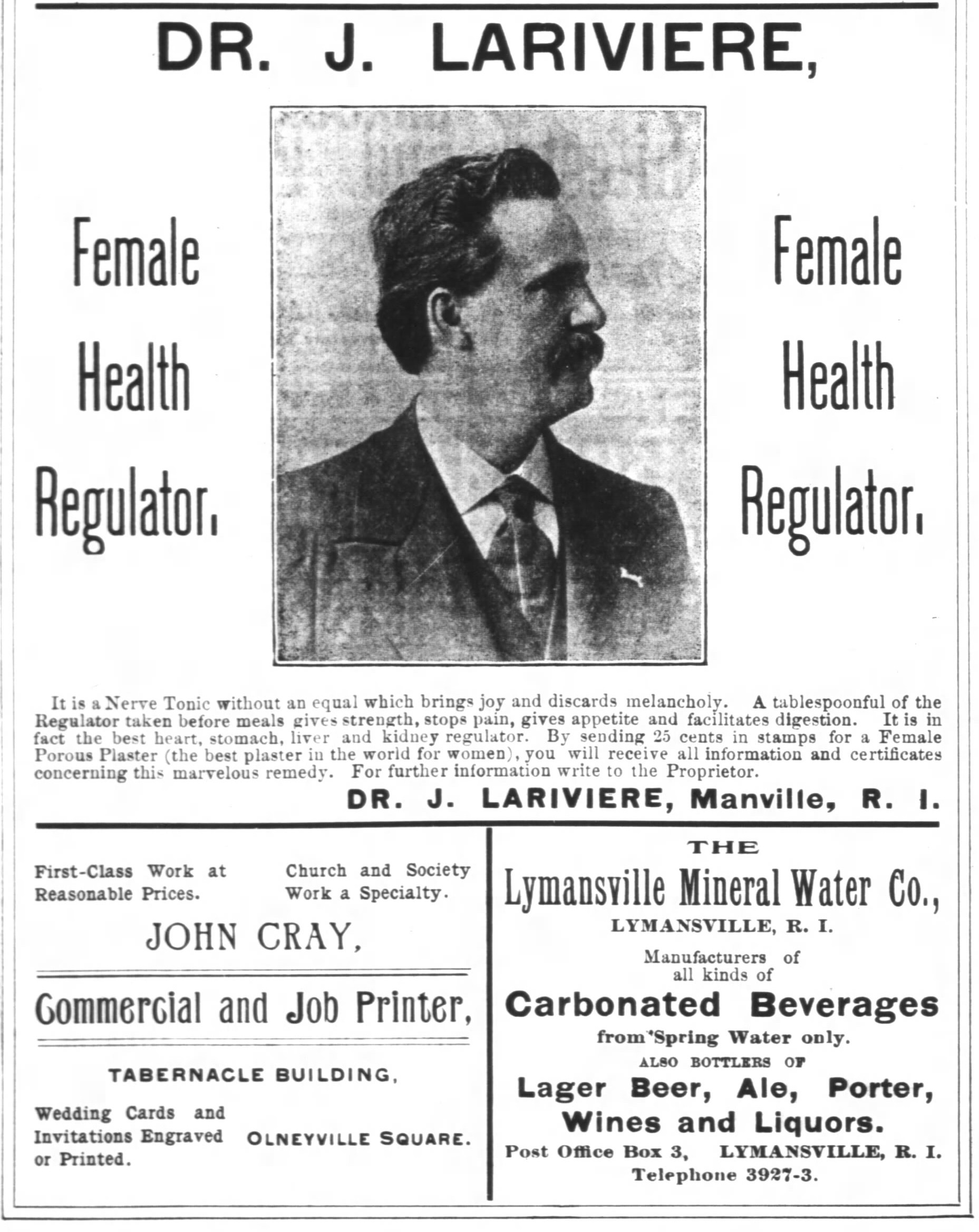

2. Dr. J. Lariviere’s Female Health Regulator

Joseph Lariviere was either intentionally clever or brilliantly ignorant. Living in the mill village of Manville, he decided to sell a concoction called Lariviere’s Female Regulator. He probably received justified backlash from the original name, as he changed it to Female Health Regulator, which apparently was less controversial, at least in the 1880s. According to an ad for it, it was a nerve tonic which “brings joy and discards melancholy.”

I was able to acquire the documented variant from a fellow collector, and a few years later I had the great fortune of digging up an early unlisted variant in a mill village community dump. One bottle had a location, Providence, R.I.

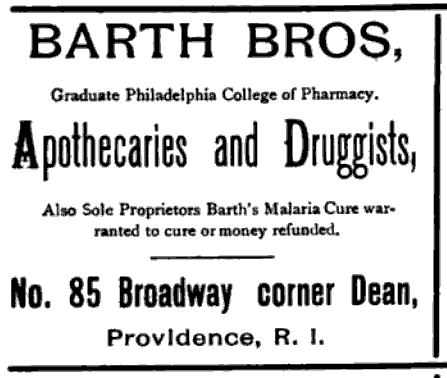

3. Alfred Barth Malaria Cure

Living in a city in the 1800s was no picnic. Unsanitary conditions led to a number of rampant diseases. One disease, in Providence surprisingly, was malaria. Unlike most quack medicines the one by the Barth Brothers (or Alfred Barth alone), located at 85 Broadway in Providence, might have actually worked because it contained some quinine, which is known to be effective against malaria. Still, a potential customer then might have paused when he or she looked at the bottle above and saw malaria misspelled as maleria.

This rare bottle is documented by the Little Rhody Bottle Club. I obtained permission to look for bottles at a downtown construction site a couple years ago and this was one of the best bottles I found there.

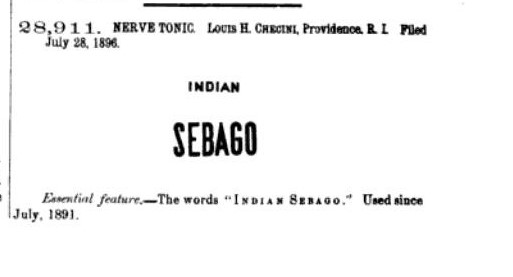

4. Checini’s Indian Sebago, The Great Blood Purifier

Louis H. Checini of Providence sold his “Indian Sebago.” Sebago means “great water,” though it is unclear if this had meaning or if it was just an Indian word he used to make it sound more exotic. It was advertised in the 1890s as a “nerve tonic” that purified the blood and killed worms. By 1902 it appears he had switched from the patent medicine business to the mineral water business.

Customers may have thought that Checini was an Indian name, but it was likely an Italian one.

Until a few years ago I was only aware of one documented example of this bottle. I now know of three, including the one I own, which I purchased from a friend.

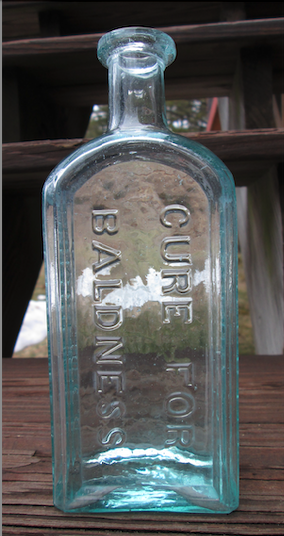

5. Cure for Baldness

Most quack medicines of the day included an opiate that made the user feel good and went a long way towards convincing the user that the medicine was working. When it comes to growing hair, however, seeing is believing, and it appears this one from James M. Curtis was a failure. Ads for this product were first seen in 1858 and last seen in 1863. That same year Curtis switched to selling tobacco.

My bottle was found by a fellow bottle digger in an old outhouse that was located underneath a building. It was badly stained, which allowed me to obtain it for a reasonable price. I then had it carefully cleaned by an expert “bottle tumbler,” Leo Goudreau.

6. Dr. Murphey’s Elixir of Life

Francis Murphey had minor success peddling his concoction in Westerly. While the name sounds like it should restore your health similar to the fountain of youth, an ad for it claims that it cured all manner of digestive issues. The customer base for the Elixer of Life must have been sold, as when Murphey died in 1880, Walter Price, a pharmacist who also dabbled in quack medicine, bought the rights to produce and sell Murphey’s Elixir of Life. This was one of the few Rhode Island quack medicines that also came in a sample size, which was usually given away for free in an attempt to entice more customers.

Like many patent medicines, there is no town embossed on the bottle. This enabled me to get lucky and buy one right in an antique shop in downtown Westerly. I was also able to buy the sample size from a fellow collector from Connecticut. I was even luckier two years ago when I found a small farm dump while surveying and dug up two of them with a friend.

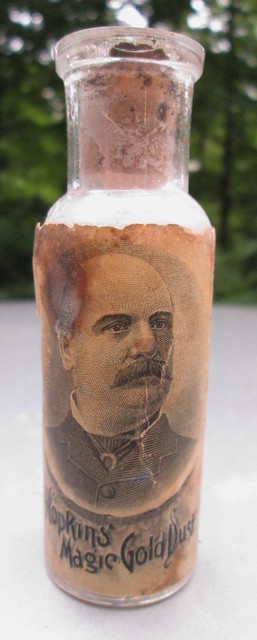

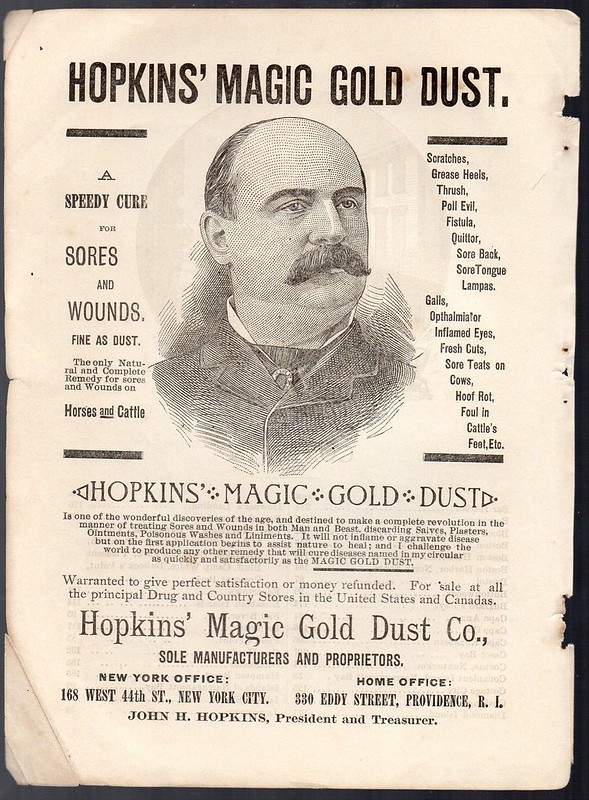

7. Hopkins’ Magic Healing Powder and Gold Dust

Andrew J. & John H. Hopkins were so confident in their creations that they were bold enough to call them magical! Andrew was a veterinary doctor starting his practice in the 1840s. When the Civil War broke out he enlisted and was given the title of chief veterinary surgeon. He returned from the war after he broke his leg. His interests turned to quack medicine, and he began to sell Hopkins Magic Healing Powder. This product was said to be for the treatment of cuts, scratches, and other wounds for “Man or Beast,” though many of the ailments it advertised it could cure where of the animal variety. It appears Andrew Hopkins changed the formula because in 1870 he filed a patent for an “Improved Magic Healing Powder.” It appears he went out of business around 1880.

I was lucky enough to find all three versions of his rare bottles—by purchasing them. The first one I found at a bottle show, the second I saw on eBay, and the third came from a collector in southeastern Massachusetts.

I have yet to discover Andrew’s relationship with John. They were likely brothers. It seems to be more than coincidence that they shared the same last name and both dealt in “magical” remedies. John’s business began in 1875 when he patented his Magic Gold Dust. His advertisements indicate he had offices both in New York City and at 330 Eddy Street in Providence. John appears to have had little success, based on the scarcity of his bottles. I had the good fortune of acquiring a fully labeled bottle on eBay a couple years back.

(All photographs of bottles in this article were made by the author of bottles in the author’s collection).