Rhode Island from its earliest days as a colony had a large degree of political freedom. Unlike most other English colonies that had either an appointed royal governor, such as Massachusetts, or a proprietary governor, as in the case of Pennsylvania, Rhode Islanders proudly elected their governor and all other state officers. Based on its Royal Charter of 1663, freemen of Rhode Island were accustomed to electing their governor, deputy governor, and ten assistants, plus attorney general, secretary of state, and treasurer on one ballot. Beginning in 1799 the term deputy governor was replaced with lieutenant governor and the ten assistants were renamed senators.

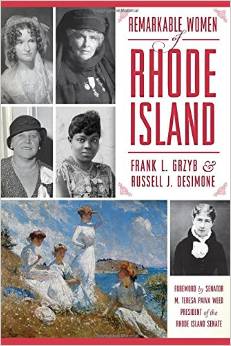

Figure 1: 1832 election prox with name of candidate for governor left blank (Russell J. DeSimone Collection).

Typically, the gubernatorial candidate who received a majority vote was declared the winner. During the nineteenth century, however, problems with this process began to occur. Occasionally a majority was not achieved and a subsequent election (either by the electorate or by the General Assembly) was necessary. This situation most notably manifested itself in the general election of 1832, but it also occurred in ten other elections during the nineteenth century until finally an amendment to the state constitution was ratified allowing for candidates to be elected by a plurality.

Rhode Island elections even led to a new term: a “no choice” election. The term ‘”no choice” was used to describe any general election in which a candidate failed to receive a majority of the vote.[1]

The first “no choice” election for governor occurred in April 1806, however the cause for this can best be understood byevents occurring in both 1804 and 1805. The popular Arthur Fenner had been governor since 1790 and by 1805, now age 59, he was in poor health. The health of lieutenant governor Paul Mumford of Newport, at 71 years of age, was no better. In June 1804 the General Assembly, recognizing that Fenner was too ill to serve out even his current term, passed a special act temporarily authorizing the lieutenant governor to perform the duties of the governor. Despite their poor health, both men ran for office again in 1805 and won with little opposition. Only two months into the new term of office, Lieutenant Governor Munford died on July 20, 1805, and Governor Fenner followed him to the grave on October 15. The void of leadership resulting from these two deaths was filled initially by state senator Henry Smith, who officiated as governor. Smith assumed the post because he was the “first senator,” meaning he was the person at the top of the list of candidates listed for senator.[2]

As the perennial governor for fifteen years, Fenner’s death left an opening for the office in 1806. Three candidates threw their hats into the ring: Henry Smith, the officiating governor and first senator, ran on both the Democratic Republican prox [3] and the Consistent Republican prox; Peleg Arnold ran on the Real Republican prox; and Richard Jackson, Jr. ran as a Federalist. Jackson received the most votes, 1,662, while Smith had 1,097 votes and Arnold 1,094 votes. Without a clear majority, the newly elected lieutenant governor, Isaac Wilbour, officiated as governor for the full term until a new governor could be elected in 1807.[4]

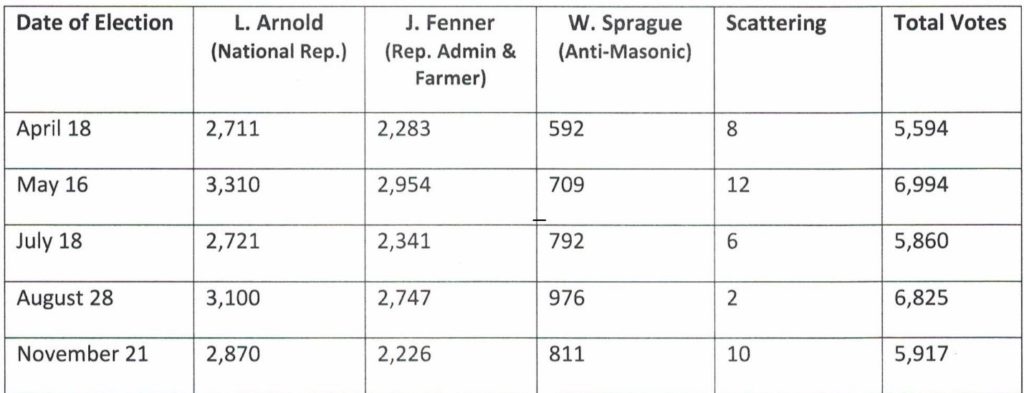

The contest for governor in 1832 proved to be problematic. Not only did the April election result in a “no choice” but four additional elections that year had the same “no choice” results. In all there were five elections in 1832 – April, May, July, August, and November. During this span of time some of the candidates for lesser positions on the ballot were replaced, certainly an attempt on the part of the political parties to better position themselves in order to break the deadlock.

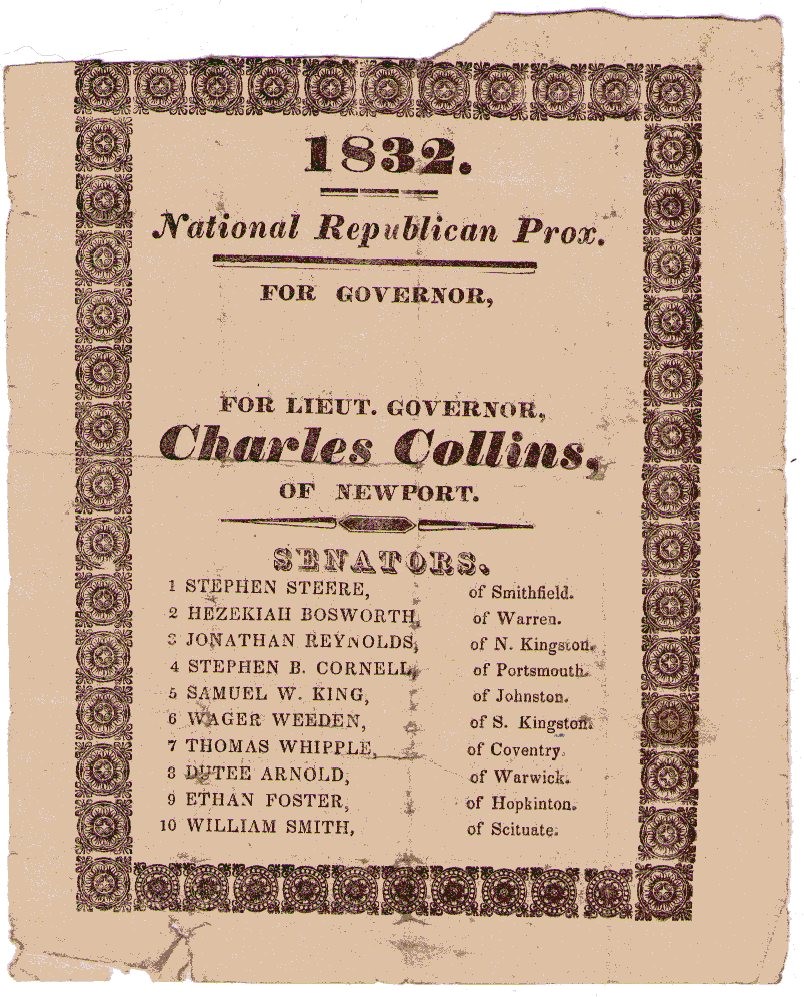

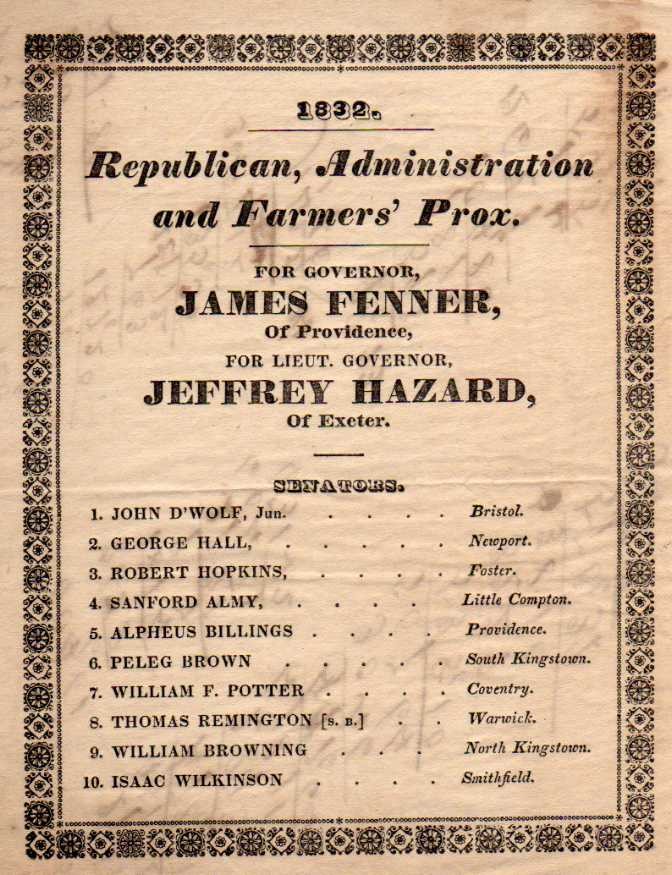

In all five elections in 1832, incumbent governor Lemuel Arnold, running on the National Republican prox, was challenged by James Fenner [5], a former governor running on the Republican, Administration & Farmers’ prox, and William Sprague [6] running on the Anti-Masonic prox. Arnold’s running mate for lieutenant governor was Charles Collins, but a rift in the party caused Arnold to recommend dropping Collins from the ticket. In response, some of Collins’s supporters printed a prox leaving the name of the candidate for governor blank so that the voters could write-in the name of another person (see Figure 1).

The prox for the Republican, Administration and Farmer’s parties for 1832, one of the “no choice” years (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

During this timeframe there were strong anti-Masonic sentiments across the country and for a while this caused the third-party Anti-Masons to come into existence. As often was the case with a serious third-party campaign, the third-party candidate drew enough votes to deprive the leading candidate of a majority. In all five elections in 1832, Arnold received the most votes, but votes for Sprague caused a “no choice.” Table I provides a summary of the election returns. Upon careful review of these returns it is evident that Arnold’s best chance for a majority came in the April election when he missed being elected by only 87 votes.

Shedding significant insight into the difficulties of the 1832 election impasse is an undated draft of a letter written by John Brown Francis, presumably to then Governor Lemuel Arnold. Francis wrote:

Private

Dr. Sir,

In consequence of your intimation a fortnight since that you wish to retire from the Chair, provided a new and satisfactory arrangement could be made, I feel emboldened to say that a state of things has arisen which may have the effect of giving us an election of governor – for, I am assured that two of the candidates offer to withdraw on condition that I consent to suffer my name to be placed at the head of their respective proxies and without exacting from me any pledge as to Jacksonism or Anti-Masonry. All that is asked of me is silence, or such a course as similarly situated Dr. Messer took, a year or two since.

The motive urged upon me to accept this proposition is that I hereby put an end to the triangular warfare but, it would bring me in opposition to you.

In this emergency you will not esteem it indecorous or unfriendly in me to say that I am perplexed as to the path to be taken.

If I decline, both Fenner & Sprague will again be run, and the state probably subjected to the trouble and expense of another election – not so if I accept.

What I have said is of course strictly confidential as any communication from you to me will be considered.

What Arnold’s response to Francis’ letter was we will never know, but the offer to settle the impasse was never acted upon. After five failed elections Arnold continued in ‘”the Chair” as governor until the election of 1833 when he was defeated by John Brown Francis by a vote of 4,025 to 3,272. Both the Democratic Republicans and the Anti-Masons endorsed Frances so that while three parties ran tickets only two candidates were put up for election thereby avoiding anther election impasse.

The 1832 prox for the National Republican Party, this time with the name of the candidate for governor filled in (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Just seven years after the multiple elections of 1832 another statewide election resulted in no gubernatorial candidate achieving a majority. In 1839 three candidates ran for governor: William Sprague, the Whig candidate, was the incumbent; Nathaniel Bullock ran on the Democratic Republican and Farmers’ prox; and Tristam Burges ran on the Liberal prox. The Providence Journal, a Whig newspaper, noted “There are two proxes offered to the freemen which are composed partly of Whigs and partly of Loco Focos. The ‘Liberal Prox’ has upon it the names of two candidates on the Whig Prox, and one on the Loco Foco Prox. The ‘Temperance Prox’ or the one recommended by the Temperance Herald contain six Whig and four Loco Foco names. Now we trust no Whig will vote for a ticket which contains the name of a single Loco Foco . . . .”[7]

It was not unusual at this time for election tickets to have a mix of candidates from the various parties. Ironically, the Temperance prox complained of by the Whig newspaper Providence Journal was headed by a Whig, William Sprague, as its candidate for governor. Election day results on April 17 showed that while Sprague received the most votes, 2,908, he was shy of a majority. Nathaniel Bullock received 2,771 votes, Tristam Burges had 457 votes [8], and others received a scattering of 37 more votes.[9] With a total vote of 6,174, Sprague was short of a majority by 179 votes. Likewise, in the count of votes for lieutenant governor, no one candidate received a majority. Without an elected governor or lieutenant governor, the first senator, Samuel Ward King of Johnston, acted in the capacity of governor for the remainder of the term. Such turmoil boded well for King as he would be the successful candidate for governor in the next three elections.

In the aftermath of Rhode Island’s tumultuous Dorr Rebellion in the spring of 1842, a new constitution was drafted in September and went into effect the following year. Article Eight, Section Ten, of the new constitution stated, “In all elections held by the people, under this constitution, a majority of all the electors voting shall be necessary to the election of the persons voted for.” Section Seven of the same article stated in part, “If no person shall have a majority of votes for Governor, it shall be the duty of the grand committee to elect one by ballot from the two persons having the highest number of votes for the office.” Thus came into existence the Grand Committee, consisting of a joint assembly composed of incoming members of the Senate and outgoing members of the House of Representatives. It would be called upon seven times during the remainder of the century to select a governor, until an amendment to the constitution allowing for a plurality to elect a candidate for office went into effect in 1894.

The year 1846 witnessed Rhode Island’s eighth “no choice” election of the century. Byron Diman, a former lieutenant governor in 1840 and 1841, running on a Law & Order ticket, challenged the incumbent governor Charles Jackson, a Democrat, who came into office the previous year on a pro-Dorr, Liberation platform.[10] The race was close with Diman receiving 7,477 votes to Jackson’s 7,389. A scattering of 155 votes made all the difference. Usually in a race with just two candidates, a majority could be achieved, but in close races the scattering of a few hundred votes could drive the election into Grand Committee. The election of 1846 was notable for two reasons: first, it was the only “no choice” election in the nineteenth century with just two candidates competing, and second, it was the first time an election was decided in Grand Committee. On Tuesday May 5, 1846, the General Assembly met in Grand Committee and elected Byron Diman governor by a majority of 22 votes.[11]

It would be nearly thirty years before another “no choice” election occurred. In 1875 the field of candidates consisted of Rowland Hazard on the Republican & Prohibition tickets; Henry Lippitt on the Republican ticket; and Charles Cutler on the Democrat ticket. That year the prohibition issue divided the Republican Party. Cutler ran a distant third, but the two Republican candidates were separated by only several hundred votes with Hazard having the lead. As the Providence Journal noted the day following the election, “The vote of Mr. Hazard is more than three-fourths of that of the entire Republican vote of last year; he leads the list; he will go into the Grand Committee as the choice of the majority of Republicans of Rhode Island. Mr. Lippitt’s vote is the result of …. an alliance with the liquor interest and the using of means unrecognized by the friends of the leading candidate, and brought into the contest only, we hope, by the foreign allies of the ‘regular’ Republican nominee.”[12] The prognostication of the Journal proved incorrect. On May 25 the Grand Committee cast 70 votes for Lippitt and 36 for Hazard, making Lippitt the state’s new governor.

The following year, the Centennial of the United States, the election of the President ended in doubt. Samuel Tilden won the popular vote handily but was one vote shy of the necessary 185 electoral votes needed to be declared President. With the U.S. Congress split between a Democratic dominated House of Representatives and a Republican dominated Senate, the decision fell to a Federal Electoral Commission to decide the election’s outcome.

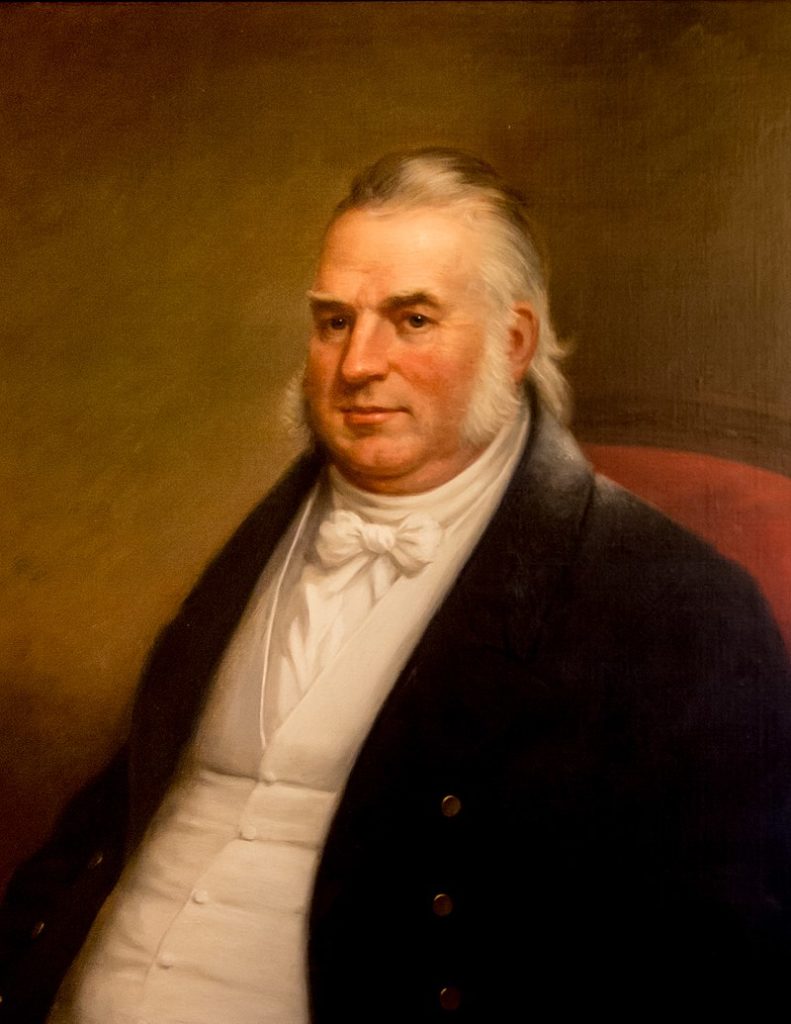

James Fenner was elected governor in the annual elections of 1807-1810, 1824-1829, and 1843-1844 for a total of 12 terms. Combined with his father’s 16 terms as governor, this father-son team served an impressive 28 years as Rhode Island’s chief executive (Rhode Island State House Collection)

Back in Rhode Island the April 5 election of statewide officers also resulted in a “no choice” for governor. Governor Lippitt, a Republican, received 8,689 votes, while Albert Howard, a Republican & Prohibition candidate, received 6,733 votes, and William Beach, a Democrat, received 3,599. In May the General Assembly met in Grand Committee and once again elected Henry Lippitt to the governor’s chair.

Four years later, in 1880, another “no choice” resulted in no one being elected governor in the regular election. This year, as was the case in 1875 and 1876, three candidates ran for governor: Alfred Littlefield, a Republican; Albert Howard, the Republican & Prohibition candidate; and Horace Kimball, a Democrat. Again, the temperance movement threw the election into doubt. More than 22,000 voters turned out on election day, April 7, casting 10,234 votes for Littlefield, but it was insufficient for a majority. The determination of the state’s governor was once again turned over to the Republican-dominated General Assembly. On May 25 the General Assembly, meeting in Grand Committee, elected Littlefield. He received 82 votes to Kimball’s 20.

It would be almost a decade before another “no choice” general election took place, andit came as a harbinger of other non-productive general elections. “No choice” elections occurred in 1889, 1890, 1891, and 1893. It was obvious that something needed to be done to correct the occurrence of so many elections without producing a winner.

The elections of 1889, 1890 and 1891 can readily be categorized. In each of these years John Davis, a Democrat, faced Herbert Ladd, a Republican. In each of these elections other serious candidates also ran. In 1889 James Chace ran as the Law Enforcement candidate, while Harrison Richardson ran on the Prohibition ticket. In 1890 John Larry ran on the Prohibition ticket while Arnold Chace ran on a Union ticket, and in 1891 John Larry ran again on the Prohibition ticket and Franklin Burton ran on a National ticket. While none of these third-party candidates received many votes, they did receive enough support collectively to throw the election of governor into the hands of the Grand Committee.[13] While Davis bested Ladd in all three elections, the Grand Committee in a sort of see-saw manner elected Ladd in 1889, Davis in 1890, and Ladd again in 1891. Not surprisingly, results of these Grand Committee elections always favored the candidate of the party in power in the General Assembly.

The election of 1893 was unlike any other—nobody was elected governor. Incumbent governor D. Russell Brown, a Republican, faced Democrat David S. Baker and Henry B. Metcalf [14], running on the Prohibition ticket. The day following the election the Republican newspaper, the Providence News, reported 22,081 votes for Governor Brown, 22,073 for Baker and 3,206 for Metcalf.[15] With less than a dozen votes separating the two leading candidates it was practically a dead heat.[16] Party politics ran high in the lead-up to the election. The Republican ticket printed in the Providence News the day before the election contained the following exhortation: “Your Votes are Needed to Save the State. These Men Represent Good and Uniform Government as Opposed to Ballot Burners and Constitution Destroyers. The Only Hope of the Democrats is that You Will Stay at Home. Providence is Republican if Every Man Votes. Your Business Interest Will Suffer if You Allow the Party Voting on Dead Men’s Names to Control the State. Vote Early and Endorse a Good Administration.”[17]

Normally with a “no choice” in the general election, the decision would have resorted to the Grand Committee of the General Assembly, but with Democrats firmly in control of the House of Representatives and Republicans in control of the Senate the two houses refused to meet in Grand Committee. As such, the state officers of the previous year carried over, in effect giving the governorship to the incumbent Republican, D. Russell Brown.[18]

In the nineteenth century between the years 1801 and 1893 there were 97 general elections, including the 5 in 1832. Of these elections 15 resulted in “no choice,” meaning that more than 15% of the time the effort and expense of a general election resulted in no one being elected governor. Counting the general election of 1832 only once, 11 general elections ended with a “no choice.” When the decision resorted to the Grand Committee, the results went to the party in power, regardless that the candidate receiving the greatest number of votes was running under a different party’s banner. With the frequent occurrences of third party candidates running for office it was evident that “no choice” elections would continue unless something was done to resolve the requirement for the winner to achieve a majority vote.

The relief came in the form of a proposed constitutional amendment, which read in part, “Section 1. In all elections held by the people for state, city, town, ward or district officers, the person or candidate receiving the largest number of votes cast shall be declared elected.” In November 1893 voters approved this proposed amendment and it became Article X under Articles of Amendments of the state constitution.

For the remainder of the century, each election had four or more candidates running for governor. Yet in all of these elections the successful candidate received a majority of the votes and would have been elected without the adoption of the new constitutional amendment. Still, with the passage of Article X, a long and painful chapter in Rhode Island election history came to a close.

[Banner image: The prox for the Republican, Administration and Farmer’s parties for 1832, one of the “no choice” years (Russell DeSimone Collection)]

Notes

[1] The term ‘”no choice” was used throughout the nineteenth century until a plurality replaced a majority as the requirement for election. [2] Senators were elected by position on the list and not just by name. Votes were counted by position so that a candidate had to receive a majority of votes in a particular position and votes for that candidate in any another senatorial position were not counted. [3] A prox was a ticket (usually printed but sometimes manuscript) listing candidates for office and presented to the people for their vote. Until the advent of the Australian Ballot System in 1889 proxes were issued by political parties; after 1889 the Secretary of State was responsible for the printing and distribution of all statewide election ballots. [4] The election of 1807 did at least produce a lieutenant governor; however, other “no choice” elections throughout the remainder of the century did not provide the needed majority for the position of lieutenant governor. [5] James Fenner, son of Governor Arthur Fenner, served as governor longer than any other person in Rhode Island history, with the exception of his father. James Fenner was elected governor in the annual elections of 1807-1810, 1824-1829, and 1843-1844 for a total of 12 terms. Combined with his father’s 16 terms as governor, this father-son team served an impressive 28 years as Rhode Island’s chief executive. [6] William Sprague was elected governor in 1838. In 1842 he was elected by the state senate to the US Senate to fill the unexpired term of Senator Nathan F. Dixon, who died in office. [7] Manufacturers and Farmers’ Journal, April 11, 1839. The term “loco foco” derives from a wing of the Democratic Party in New York City, but in time came to be used to describe any member of the Democratic Party. [8] Burges’s low vote count can be attributed to the fact that one week before the election he wrote a letter to the editor of the Providence Courier stating that his health was such that he could not accept the nomination. [9] The scattering of votes was mainly attributed to a Temperance Prox that was floated near election time. The Providence Journal claimed this prox was intended to dilute the votes cast for the Whig candidate. [10] The Law & Order ticket was a coalition of Whigs and moderate Democrats joining together to oppose the radical actions of the suffrage reform movement lead by Thomas Dorr. The Dorrites ran in their own extralegal election under the name of the People’s Party. The Liberation ticket was formed by a movement on the part of concerned citizens for the release from prison of Thomas Dorr following his trial, conviction and life sentence for treason against the state. [11] Bristol Phenix, May 9, 1846. [12] Manufactures and Farmers’ Journal, April 8, 1875. [13] For the election results of these years, as well as other years, see the applicable edition of the Rhode Island Manual. [14] In 1900 Metcalf ran as the national Vice-Presidential candidate for the Prohibition Party. [15] Providence News, April 6, 1893. [16] Because the two chambers of the General Assembly were in disagreement and never convened, the final official election results were never recorded. [17] Providence News, April 4, 1893. [18] See Edward Field (ed.), State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History (Boston, 1902), Vol. 1, p. 387.