Lotteries are said to have had their beginnings in Europe. Some say it was in Renaissance Florence with the advent of the game “Lotto” and there is some evidence of a lottery in Bruges in the year 1446. Certainly lotteries existed in England during the 16th century. John Aston in his book A History of English Lotteries states the first English lottery was drawn in 1569. The first American lottery was in 1612 when the Virginia Company of London received a charter from Parliament for a lottery for the benefit of the Jamestown settlement. By the mid-18th century lotteries were used in all the thirteen American colonies. They helped raise money for community projects as well as for private purposes.

Rhode Island lotteries are thought to have existed from the colony’s earliest days of the 17th century. While no written records of these lotteries exist, the Rhode Island legislature found it necessary in 1732 to prohibit their further use. In so doing Rhode Island was following some other colonies in their abolition. Massachusetts in 1719 “forbade unauthorized lotteries,” followed by New York in 1721, Connecticut in 1727 and Pennsylvania in 1729.

While the history of lotteries in 18th and 19th century Rhode Island is interesting, little of their significant role in everyday life is fully appreciated today. In a time when taxation was limited, hard money in short supply, and banks non-existent, it fell to the lottery to be the primary method of raising funds for a variety of civic and religious projects. From 1744 to the end of the colonial period, the Rhode Island General Assembly authorized almost as many lotteries as all of the other twelve British colonies combined. By 1842, the Rhode Island legislature had authorized nearly 250 lotteries. This is an impressive number when one considers the size of the state and surprising in light of the new state constitution prohibiting them altogether. The role of lotteries in providing the revenue for public works, such as the building, repair and maintenance of roads, bridges and wharves was significant. They were also used by towns, as well as civic and religious societies, to provide the necessary capital to build school and meeting houses, churches, Masonic halls and armories. Lotteries were also used for a variety of innovative purposes including payment of personal debts of private citizens and in one case for the payment of a ransom.[1] Toward the end of their existence in 1842, lotteries were the primary source of revenue for the nascent public schools of the state.

The first recorded lottery in Rhode Island was in 1744. Before this, lotteries were conducted from time to time but not with the sanction of the colony’s government. Lotteries likely existed in the colony during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Lotteries were common in Europe during the 1600s and the practice was brought to the New World by the first English settlers, so it stands to reason that the practice would have been used in Rhode Island as well, but no records exist of these early lotteries. That these pre-1744 lotteries did exist is evidenced by an enactment, during the January 1732 session of the General Assembly, outlawing them and imposing heavy fines on those who would break the law.

An ACT for Suppressing of Lotteries

WHEREAS there has been brought up within this Government, certain unlawful Games, called Lotteries, whereby unwary People have been led into foolish Expence (sic) of Money, which may tend to the great Hurt of sundry Families; and also the Reproach of this Government, if not timely prevented:

For Remedy whereof,

BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly, and by the Authority of the same, it is Enacted, That no Lottery shall be published or set forth within this Government, from and after the Publication hereof; and that from and after the thirtieth Day of April, Anno Dom. 1733, none shall publickly or privately exercise, keep open, show, or expose to be played at, thrown at, drawn at, or shall draw, play, or throw at any such Lottery, either by Dice, Lots, Cards, Balls, or any other Numbers or Figures, or any other Way whatsoever; and every Person so exercising or drawing any such Lottery, in Manner as aforesaid, shall for every such Offence, forfeit Five Hundred Pounds: To be recovered by Bill, Plaint, or Information, of Action of Law, in any Court of Record within this Colony: One half whereof for the Use of the Colony, the other half to the Informer, or Person suing for the same. AND be it further Enacted, That every Person that shall play, throw, or draw at any Lottery, after the aforesaid thirtieth Day of April, shall forfeit for every such Offence, Ten Pounds: To be recovered in Manner as aforesaid, for the Use aforesaid. And for the more effectual Suppressing said Lotteries, after the thirtieth Day of April, all Justices, Judges, Sheriffs, Constables, and all other Officers, within their respective Jurisdiction, and hereby empowered and required to suppress and discountenance the same.

In October 1744 lotteries were once again permitted within the Colony with the “leave of the General Assembly.” Until their abolition in 1842, all Rhode Island lotteries, with one notable exception, were granted by the General Assembly. The exception occurred in 1779 when Major General Richard Prescott, commander of the British forces occupying Newport, granted the Loyalist inhabitants a lottery “to carry into execution such measures as may be necessary for the promotion of His Majesty’s service.”

Lotteries prospered in mid-18th century Rhode Island. An early chronicler of Rhode Island lotteries noted, “Of the 158 lotteries authorized in all of colonial America from 1744 to 1774, 75 were in RI (47.4%). By contrast only 22 lotteries were authorized in much larger Massachusetts and just 15 in NY.”[2]

18th Century

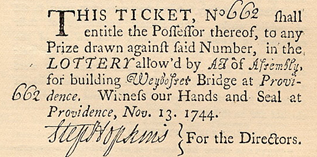

Rhode Island’s first lottery, following the lifting of their prohibition in 1732, was in 1744 for the building of Weybosset Bridge in Providence (see Figure 1). Note this ticket was signed by Stephen Hopkins, many times governor of the colony and a future signer of the Declaration of Independence. (Many other famous Americans, including George Washington and John Hancock, acted as lottery managers and as such signed lottery tickets.)

Not all lotteries during the 18th century were for improvement to public infrastructure. Indeed many were for other purposes.[3] Just four years after allowing for the return of lotteries, the first in a long line of lotteries was granted for the relief of a private individual. It occurred when Joseph Fox of Newport was granted a lottery in 1748 to raise £3,000 to pay off a debt that had kept him in debtor’s prison for two years.

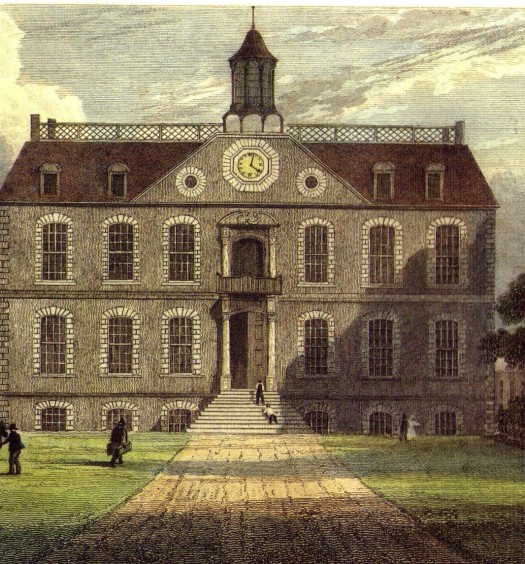

When lotteries were not being permitted for infrastructure improvements or personnel debt they were being granted for civic initiatives such as churches, schools and libraries. For example, Rhode Island College, now Brown University, considered petitioning the General Assembly for a grant, but then as now, there was some pushback on gambling. On May 19, 1772, Dr. James Manning, President of Rhode Island College, wrote to John Ryland, a friend in England, “Would a well concerted scheme of a lottery to raise £1,000 or £2,000 sterling meet with encouragement by the sale of tickets in England?” Ryland replied, “We have our fill of these cursed gambling lotteries in London, every year they are big with ten thousand evils. Let the Devil’s children have them all to themselves, let us not touch or taste.”[3] Not heeding the warning thirteen years later on December 23, 1795, the college formed a committee charged to request the General Assembly to grant it a lottery. In 1796 the college received a lottery grant of $25,000 for its general use. Jonathan Maxcy, successor to Dr. Manning as college president, personally took 303 tickets to sell at six dollars apiece but was able to sell only 168 of them.

Proving that nothing last forever, the Weyboset Bridge, first built with the aid of £3,000 from a 1744 lottery, fell into disrepair. A new bridge was constructed with the proceeds of yet another lottery of $3,000 granted by the General Assembly in 1790.

19th Century

During the first quarter of the 19th century, lotteries—much like those of the previous century—continued to be used to support the infrastructure of the state’s roads, toll-roads, bridges and wharves, as well as its churches, libraries and Masonic halls. However, during the second quarter of the century, lotteries were almost exclusively used for public schools. Interestingly, unlike the 18th century, there were no lotteries for the financial relief of individuals.

Also during the 19th century the first action to regulate lotteries since 1732 came in 1806 at the February session of the General Assembly, when it passed “An Act for Suppressing of lotteries not authorized by law and to prevent the sale of any tickets in such lotteries.” The new law forbade the sale or advertising of any lotteries not authorized by the state or Congress, and set fines from $10 to $100 for each offense. The fines were to be distributed half to the state and half to the informer. Anyone buying such illegal tickets could recover their cost in court.

At the turn of the 19th century, it was common for lottery grantees to sell their General Assembly grants to lottery management companies and thereby forego the burden of administering the lotteries themselves. Lottery management soon became big business throughout the country with such firms as Yates & McIntyre and Paine & Burgess rising to prominence. These management companies were responsible for the printing and sale of tickets, advertising and oversight of drawings, the disbursement of prizes, and the reporting of their sales and commissions due to the state. Some of these management companies also loaned money, cashed checks and converted out of state money. Some companies even went on to become banking institutions. Lottery offices and their agents appeared in many towns and local town governments collected licensing fees from each agent. These ticket agents advertised extensively in the local newspapers and gave their offices promising names such as: J. Howard’s Fortunate Office and Allen’s Truly Lucky Office, both in Providence, and Walker’s Truly Lucky Office in Woonsocket. These lottery offices sold tickets to many lotteries at any given time and were agents for foreign (out of state) lotteries as well. Newspapers made healthy profits on all the lottery advertisements that appeared in many editions.

It seemed as everyone was making money in the lottery business except those who bought tickets.

From 1800 to 1825 the General Assembly granted nearly seventy lotteries. Among them were two unusual lotteries to explore for coal, one on Aquidneck Island and the other in Cumberland. Both were granted in 1812. (It was later quipped that the coal discovered on Aquidneck Island would not burn in hell.)

The concept of a lottery for the support of public schools was first presented in Newport with the Long Wharf, Hotel and Public School lottery in 1798. But it wasn’t until 1828 when the Rhode Island General Assembly passed an act providing for the support of free public schools that a statewide initiative took effect. From 1828 on all lottery grants, with one exception, had provisions for some proceeds going to public schools. Beginning in 1831 the General Assembly issued grants to lottery managers specifically for public schools; these lotteries were known as the School Fund lotteries.

However because of many irregularities, grand prizes were seldom drawn and with only minor government oversight of drawings, the business of lotteries was subject to fraud. By the 1830s , although anti-lottery literature began to appear, news of these irregularities was never published in any of the newspapers that had lucrative income from lottery advertisements.

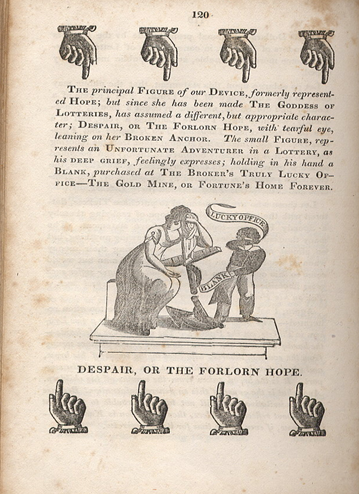

In the mid-1830s, and gaining momentum throughout the rest of the decade, a campaign developed to outlaw lotteries and expose irregularities by some lottery managers. Thomas Man, a Providence merchant and self-styled professor of languages and author, wrote the first attack. His anti-lottery treatise, Remarks on Lotteries, was published in Providence in 1833. In it is the interesting depiction (see Figure 2) of Forlorn Hope and a grieving Adventurer—the unsuccessful ticket holder. Thomas Man also penned an intriguing rhyme:

A lottery is a Taxation

Upon all the Fools in Creation;

And heaven be praised,

It is easily raised.

Thomas Doyle, future mayor of Providence and former lottery agent, wrote an exposé of the inner workings of a lottery office in 1841. This now scarce pamphlet provides excellent insight into some of the seedier aspects of the lottery business due in part to unscrupulous managers and poor oversight by the state.

Over the next decade anti-lottery sentiment grew. Other states began to prohibit lotteries. In Rhode Island, following the political turmoil of Dorr’s Rebellion, a new constitution was framed to replace the original 1663 royal charter. The constitution of 1842 brought a close to future lotteries but allowed existing lotteries to continue until the grace period date had lapsed. Article 12 in the Constitution prohibited lotteries, but it was unclear if it also outlawed out-of-state lotteries. Brown University professor William Goddard authored several anti-lottery pamphlets, including one as a petition to the Rhode Island legislature, to prohibit “foreign” lotteries in 1844. It would take another law, passed in 1846, before all lotteries in Rhode Island were ended (at least for more than one hundred years).

20th Century

In 1973 Rhode Island joined New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey and other states in establishing lotteries at the beginning of a new era of state-sponsored lotteries in the United States. On November 6, 1973 a constitutional amendment was passed in Rhode Island by a more than three to one margin to create a lottery. The amendment mandated that the General Assembly proscribe and regulate all future lotteries in the state. In March 1974 the General Assembly enacted legislation to start the lottery. The Rhode Island lottery’s original purpose was to make up for lost revenue caused by allowing the value of a traded-in automobile to be credited towards the sales tax liability on a new automobile purchase.

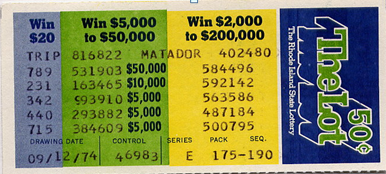

The lottery’s first drawing was held on May 30, 1974, on the lawn of the State House. It was for a fifty cent game called “The Lot.” The top prize was $50,000 with a special drawing prize of $200,000 (see Figure 3). Soon thereafter in June 1975 the Grand Lot began; by 1980 the new Grand Lot was introduced. Tickets were fifty cents and contained twenty different numbers. Each Wednesday, 3-digit, 4-digit, 5-digit and 6-digit numbers were drawn. Depending on the location of a particular winning number on a ticket, a player could win $20, $50, $500, $5,000, $20,000 or $1,000 a month for one year. The Grand Lot Running ticket allowed the purchaser to play using the same ticket for one year. The advantage of the Running Lot was that prize checks were automatically sent to the lucky winner’s home; there was no need to make a claim in person.

Figure 3 – “The Lot” Rhode Island’s first lottery of the modern era (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

In addition to the lottery’s traditional drawing of numbers, the Rhode Island Lottery used other methods of chance such as Lotto, Keno, Instant Ticket and Video Lottery Terminals to generate revenue. Rhode Island Lottery created LOTTO specifically for its first televised lottery show aired in August 1975. A promotional flyer stated, “If you like lots of action, you’ll love LOTTO. It’s the first lottery game that lets you play along. And it’s the first TV game show you can play and win at home. As the LOTTO numbers are drawn on TV, you, your family and friends mark the numbers on your LOTTO tickets. You can win everything from free tickets to $5,000 and a chance to compete for $25,000 on TV.”

While Massachusetts introduced the first instant lottery ticket in 1974, Play Ball was the Rhode Island Lottery’s first instant game. Introduced in 1976, it paid a top prize of $25,000 a year for twenty years. Play Ball is the Rhode Island Lottery’s most popular game ever. The player must outscore his imaginary opponent over nine innings in order to win a cash prize. Winning tickets of $2, $5 and $20 are entered into a Grand Slam drawing for a top prize. Tickets are issued each year during baseball season with different yearly ticket designs such as a catcher, base runner, or pitcher depicted.

Throughout the 1970s, 80s and 90s the Rhode Island Lottery introduced numerous instant games structured on a variety of themes such as sports, holidays, and summertime activities. In 1986 the Rhode Lottery commemorated the founding of Providence by Roger Williams in 1636 with the issuance of the RI 350 instant tickets and the 20th anniversary of the Blizzard of 1978 was remembered with a new game issued in January 1998. Appropriately the top prize for the instant ticket was $1,978.

The Multi-State Lottery Association (MUSL) was formed in April 1998 for the purpose of affording small states the opportunity to offer games with a higher jackpot than their population alone could generate. The Rhode Island Lottery, as a member of MUSL, has participated in MUSL sponsored lotteries such as LOTTO America and since 1992, PowerBall. Today PowerBall is offered in forty-four states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Jackpots start at $40 million and generate increased attention when the jackpot exceeds $100 million.

Beyond the traditional lottery ticket, the Rhode Island Lottery introduced Keno drawings on September 13, 1992; six days later the first Video Lottery Terminals (VLTs) were put into use at the state’s two pari-mutuel venues, Lincoln Park (Twin River Casino) and Newport Jai Alai (now Newport Grand). Both Keno and VLTs have proven very popular with the public and are now important sources of revenue for the state.

Today both Twin River and Newport Grand casinos are under the authority of the Rhode Island Lottery Commission. The concept of small local lotteries first conceived in the colonial period have come a long way and today the Rhode Island Lottery is the state’s third largest source of income. Whatever your position on gambling may be, especially government sponsored gambling, the lottery is too significant a revenue source to the state for it to go away any time soon.

[Banner Image: Rhode Island’s first lottery was in 1744 for the building of Weybosset Bridge in Providence (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Notes

[1] In 1762 the sloop Joseph sailing out of Providence was taken by the French letter of marque St. Esther l’Amerique. Samuel Dunn, captain of the Joseph, was allowed to sail his sloop home in order for it to be sold. The proceeds of the sale were to pay the ransom of William Cookoe the sloop’s First Mate who was to be held hostage in the French West Indies until the ransom could be paid. Unfortunately the sloop was lost off the coast of North Carolina. Dunn made his way back to Rhode Island and petitioned the General Assembly for a lottery in order to raise the ransom money.

[2] Charlotte Lowney, The Heyday and Death of Lotteries in Rhode Island 1820-1842 (Master’s thesis, Brown University, 1965).

[3] See Russell J. DeSimone, “A List of Rhode Island Lotteries (18th and 19th Centuries)” (2002), posted on University of Rhode Island Digital Commons at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=lib_ts_pubs.

[4] Reuben Aldridge Guild’ Early History of Brown University (Providence, 1897), p. 232.

Bibliography

Literature on Rhode Island lotteries is limited. John Russell Bartlett, during his tenure as secretary of state (1855 – 1872) wrote a series of five newspaper articles for The Manufacturers and Farmers Journal from October through December 1856. These articles were the first attempt to relate a history of Rhode Island lotteries and came only a decade after the last lottery held in the state until the modern era. In 1896 John Staples wrote a more comprehensive account, A Century of Rhode Island Lotteries 1744 – 1844, as part of the series Rhode Island Historical Tracts published by Sidney Rider. The bibliography that follows provides a list of other literature on the subject.

Bartlett, John Russell. A History of Lotteries and the Lottery System in Rhode Island. University Library, University of Rhode Island, 2003.

DeSimone, Russell J. “A List of Rhode Island Lotteries (18th and 19th Centuries)” (2002). Posted on University of Rhode Island Digital Commons at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=lib_ts_pubs.

Doyle, Thomas. Five Years in a Lottery Office; or an Exposition of the Lottery System in the United States. Boston: S.N. Dickinson, 1841.

Ezell, John S. Fortune’s Merry Wheel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960.

Goddard, William G. Memorial to the Legislature of Rhode-Island, in Favor of the Prohibition of All Lotteries. n.p., 1844.

Kinney, David G. “The Rhode Island Lottery: An Historical Perspective and An Economic Analysis.” Bachelor’s thesis. Harvard University, 1979.

Lowney, Charlotte. “The Heyday and Death of Lotteries in Rhode Island 1820-1842.” Master’s thesis. Brown University, 1965.

Man, Thomas. Picture of a Factory Village: To which are annexed, Remarks on Lotteries. Providence: printed for the author, 1833.

Stiness, John H. “A Century of Lotteries in Rhode Island. 1744–1844.” Rhode Island Historical Tracts, Second series, No. 3, Providence: Sidney S. Rider, 1896.

Tompkins, Hamilton B. “Newport County Lotteries.” Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society. No. 1(1912):1-16; No. 2(1912):1-18.