At the dawn of the 19th century, the role of women in Rhode Island politics was non-existent and the idea of extending suffrage to women was virtually inconceivable. Throughout the century—by laboring, organizing and agitating in causes both political and social (efforts that increased with the passing of each year)—women attempted to advance their suffrage cause. By the end of the century, while their goal of earning the right to vote was still not achieved, it was no longer unthinkable. The passage in 1920 of the 19th amendment to the United States Constitution, giving women the right to vote, was in large part due to the valiant efforts of women of the 19th century who paved the way.

At the beginning of the 19th century, women, much like children, were expected to be neither seen nor heard in matters political. However, by the second quarter of the century, women were active in numerous social reform movements. It would be only a matter of time before they would focus on their own suffrage cause. At mid-century women active in the political and social movements arena were primarily working with abolition of slavery and temperance societies.

In 1836, the first Rhode Island convention of abolitionists was held in Providence. Women were not permitted to be leaders, but they attended in large numbers. When abolitionist leader Henry Stanton asked the convention audience to work against slavery, regardless of loss of reputation, property, or life, the president of the convention asked all in favor to signify their pledge by standing. The official proceedings recorded that the audience “stood up through the whole house, man and woman, one living and enthusiastic mass.” Thus, as historian Deborah Van Broekhoven noted, women made it into the official record of the meeting.[1]

Spurred by the convention, women soon organized and operated their own anti-slavery societies that developed in all parts of the state. In Providence there was the Providence Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, in Pawtucket the Pawtucket Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, as well as the women-run Juvenile Emancipation Society. Southern Rhode Island had the Kent County Female Anti-Slavery Society. On Aquidneck Island there was the Newport Anti-Slavery Society, which, like some societies, had women’s auxiliary organizations.

A list of the members of the Kingston (later South Kingstown) Anti-Slavery Society in 1837 still exists. Female members outnumbered male members, 27 to 21. Four of the women were described as “colored.”[2]

Temperance reform also saw its share of female led societies. Intemperance was seen as pervasive and a threat to the wellbeing of the family unit, so it is not surprising that many women of the period became involved in this movement. These early temperance societies ultimately led to the formation of the national Women’s Christian Temperance Union in 1874.

Women’s roles in both the abolition of slavery and temperance movements had a political aspect to them. After all the state’s political parties often ran candidates on abolition and temperance platforms.

Rhode Island women formed other reform-oriented societies, such as the Employment Society, the Female Domestic Missionary Society, the Children’s Friend Society, the Providence Physiological Society, and the Association of Friendless Females to name but a few. Not content with social reform, women were also active in church and literary societies. Even women of color were involved in organized societies such as the Colored Female Tract Society and the Colored Literary Society. Clearly women were learning to find their collective voice and soon they would no longer be unseen or unheard.

In the early 1840s the newly formed Rhode Island Suffrage Association agitated for expanded male suffrage, which in turn led to the famous Dorr Rebellion. This event provided females an ideal opportunity to become heavily involved in what was primarily a political issue. Women, such as authors Catherine Williams and Francis Harriett Whipple Green, and activists Abby Lord and Ann Parlin, played significant roles in the rebellion and its aftermath. However, the rebellion was about suffrage rights for men and female suffrage was never up for consideration. Nevertheless, the rebellion offered an opportunity for women to be part of the public discourse on topics political. It was a Rhode Island first.

Nationally, the first women’s rights convention was held at Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. The convention was organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, both of whom would remain active in the woman’s rights movement for the remainder of their lives. The convention drafted a Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances that detailed the many injustices women suffered in the United States. It was the clarion call for women across the country to organize and petition for legislation to address their grievances.

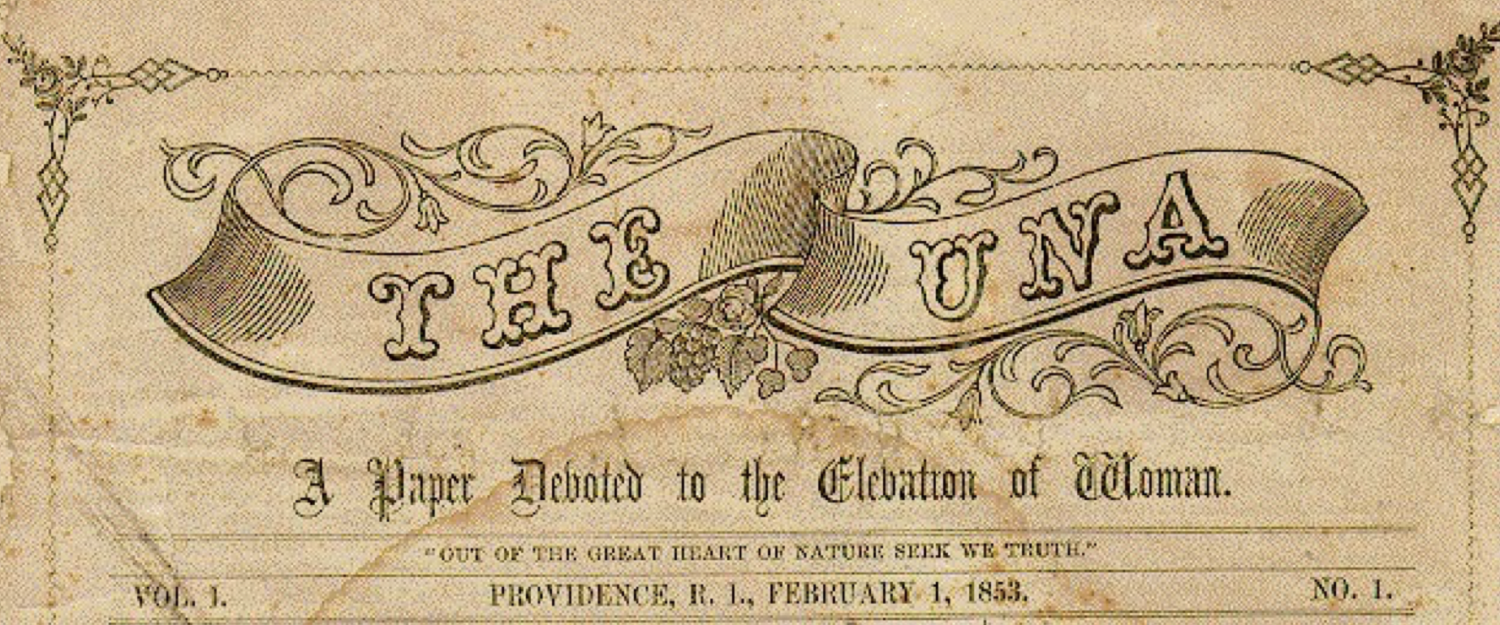

Following the death of her husband and contemporaneous to the Seneca Falls convention, Paulina Wright moved to Providence where she became active in promoting women’s health. Both she and her late husband had also been active in the anti-slavery movement. Shortly after her arrival in Rhode Island, she married Thomas Davis, a wealthy manufacturer.[3] By 1850 Paulina Wright Davis was a leader in the New England women’s rights movement. This same year she led the arrangements for the National Woman’s Rights Convention, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Not only did she preside over the convention, she also gave its opening address. She served as president of the National Woman’s Rights Central Committee until 1858. In 1853 she established in Providence, The Una, the first women’s newspaper in the nation. Its masthead proudly proclaimed, “A Paper Dedicated to the Elevation of Women” (see Figure 1).[4] Paulina Davis was a tour de force in the women’s rights reform movement and following the Civil War would become a co-founder, along with Elizabeth Buffum Chace, of the Rhode Island Woman’s Suffrage Association.

During the early years of the 1860s, the nation focused on the bitter conflict of the Civil War. Men, both young, and old marched off to war and women served in many relief efforts. Some women became involved on the home front while other women joined nursing organizations, including the United States Sanitary Commission, providing care for the wounded, sick, and dying in field hospitals. Women also performed nursing duties at Rhode Island’s only Civil War hospital located at Portsmouth Grove on Aquidneck Island.[5] Edwin Stone, in his history of Rhode Island in the rebellion, noted that the Florence Nightingale Association was formed in Providence the day following the attack on Fort Sumter. This association shortly thereafter changed its name to The Providence Ladies Volunteer Relief Association. Each ward in Providence had a relief association raising funds and contributing articles for Rhode Island’s volunteers in the field and in hospitals. The Providence Relief Association even entered into government contracts providing garments for the troops. As many as 575 women were employed in this process. Stone goes on to say, “In Newport, Bristol, Warren, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, and in every other town in the State, similar associations have been industriously engaged in like works.”[6]

The Civil War was a prime cause of drawing women out of their domestic sphere and into the public sphere. While not political in its nature the Civil War experience gained by Rhode Island women proved useful and provided them the confidence for the work ahead. Much like the genie once out of the bottle, there was no going back for these women. Certainly, a woman’s role in life would still be largely centered on the domestic sphere but from this time on she would expand her public involvement. The time for demanding women’s rights was at hand.

The end of the Civil War ushered in the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The 13th Amendment, ratified by a majority of the states in 1865, effectively ended slavery, while the 14th Amendment (1868) and the 15th Amendment (1870) addressed rights of citizenship, and voting rights. With the great work of slave abolition achieved and the Civil War ended it was now time for women to organize and demand their rights.

In November 1868 a large public meeting was held in Boston to address the subject of women’s suffrage. Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Paulina Wright Davis, both of whom were for many years the leading female voices for reform in Rhode Island, participated as members of the planning committee. The meeting was a success and resulted in the formation of the New England Women’s Suffrage Association. Buoyed by the success in Boston, the two women called for a statewide meeting to establish a Rhode Island affiliate of the New England organization. On December 11, 1868, just three weeks after the Boston convention, the Rhode Island Women’s Suffrage Association (RIWSA) was formed at Roger Williams Hall in Providence.

Not surprisingly women could not run for statewide elected office. Article IX (of Qualification for Office) of the state constitution specified that “No person shall be eligible to any civil office, (except the office of school committee,) unless he be a qualified elector for such office.” As no woman could be an elector the only opportunity available was as a candidate for local school committeeman or more precisely committeewoman.

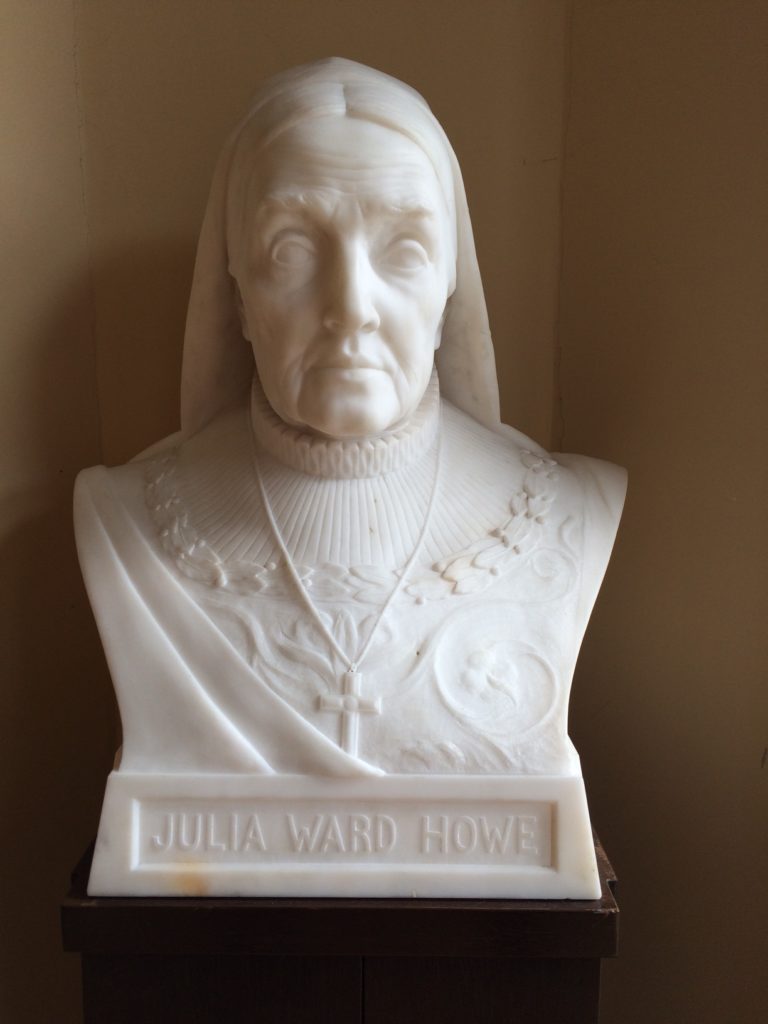

Bust of Julia Ward Howe, 1898. One of the most famous American women of her time, she organized women’s suffrage events in Newport (Newport Art Museum)

The first time women ran as candidates for office occurred in Providence in 1873 when Rhoda Peckham (Fourth Ward), Sarah Doyle (Fifth Ward), and Elizabeth Churchill (Eighth Ward) ran for the school committee. All of them were defeated. Doyle had the backing of the National Union Republicans while Peckham and Churchill ran as independents. One local newspaper implied that Doyle was cheated out of being elected, noting, “When the polls opened in the fifth ward, instead of Mrs. (sic) Doyle’s name being on the ballots for the place to which she had been nominated, there appeared the name of John W. Angell, Esq., and until about eleven o’clock a.m., he had the field to himself. At that hour, however, Mrs. Doyle’s friends appeared with the ‘regular’ nomination, and from that time to the close of the polls she received 145 votes; Mr. Angell, notwithstanding his several hours start in the race, only winning by a majority of 38. From this fact, it is clear had Mrs. Doyle’s name been in its proper place at the opening of the polls, she would have beaten her opponent handsomely.”[7]

While no female was elected in 1873 the year stands out as an historic moment when women first ventured into the political arena as candidates for election. The following year three women, Anna E. Aldrich (Fourth Ward), Elizabeth C. Hicks (Seventh Ward) and Abby D. Slocum (Ninth Ward) were all elected to the Providence School Committee. From this time on it would no longer be unusual for a woman to run for a seat on a school committee.

While women were working diligently for suffrage in Rhode Island, some western territories did in fact allow for women’s suffrage. On two occasions the Equal Rights Party ran a woman candidate for president. In 1872 Victoria Woodhull ran as the party’s nominee against incumbent president Ulysses S. Grant and Democratic candidate Horace Greely. [8] Of interest, Susan B. Anthony, the country’s leading suffragette, claiming the 14th Amendment gave her the right, registered and voted in the 1872 election in her hometown of Rochester, New York. She was arrested, tried and fined $1,000. Twelve years later Belva Lockwood ran against Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican James Blaine as well as other third-party candidates. Lockwood quipped, “I cannot vote but I can be voted for.”

In 1871, Julia Ward Howe, widely known for penning the Battle Hymn of the Republic, began spending her summers in Newport and Portsmouth, which she would do for most of the rest of her life. A founder of the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1868, she served as its president until 1877 (and again from 1893 to 1910). At a meeting of the New England Woman Suffrage Association in 1887 at the Newport Casino, she and Susan B. Anthony were the keynote speakers.[9]

Throughout the last quarter of the 19th century the prospect of women’s suffrage came into consideration. In 1882 both the United States Senate and House of Representatives appointed committees on the subject. In 1884 the Rhode Island General Assembly unanimously approved use of the State House for a women’s suffrage convention. Across the country the subject was debated but progress was painfully slow. The fact remained that the male electorate was not ready to share the vote. The reasons for this are complex and varied and outside the scope of this essay, but if reform were to come it was going to take time and a lot more effort.

Since its founding in 1869 the RIWSA annually petitioned the state legislature for a constitutional amendment to abolish sex as a condition of suffrage. This call always went unheeded but in 1885 on a bill proposed by Representative Edward L. Freeman it passed both houses but still ultimately failed. The bill again appeared in 1886 and received the required 2/3rds majority in the General Assembly. Before the issue could be voted on by the state’s all-male electorate, bills of this nature needed to pass by a 2/3rds majority in two consecutive legislative sessions, which it did in 1887 by a vote of 25 to 8 in the Senate and 57 to 5 in the House. Days before the April 1887 election newspapers printed long lists of prominent people (mostly men) who opposed passage while other lists, also of prominent people, favored its passage. The amendment needed a 2/3rds majority in the statewide vote and prospects were dim for its passage.

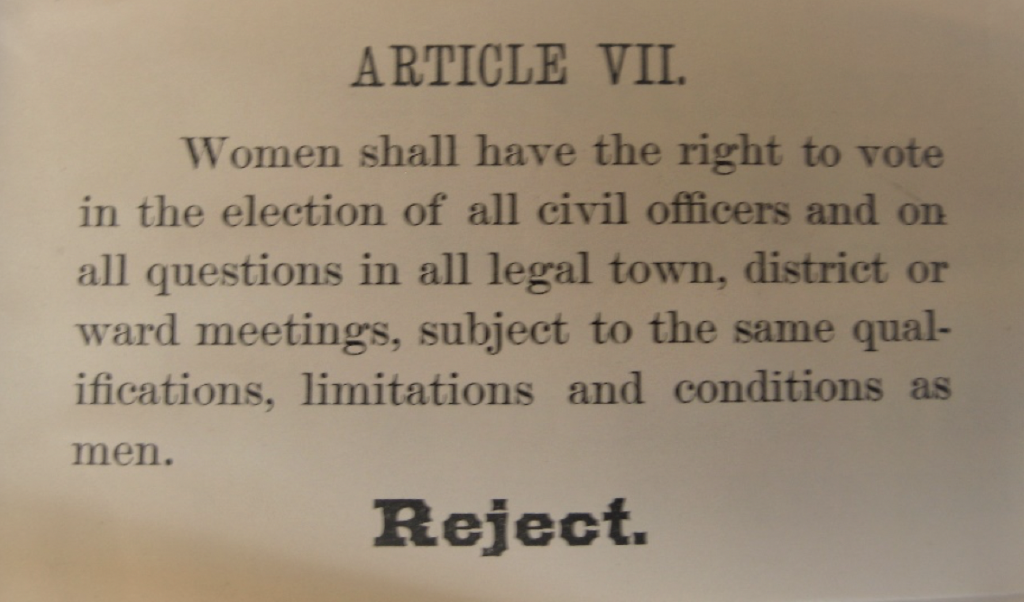

Figure 2 – Ballot for 1887 amendment to Rhode Island state constitution (Russell DeSimone Collection)

The women’s suffrage amendment went before the electorate on April 6, 1887. While some had high hopes for passage, the amendment never really had a chance – it failed miserably by a vote of 21,957 to 6,889. The Newport Daily News said it best: “The woman suffrage amendment was simply buried, completely overwhelmed by an April snow storm of ballots.” [10] While this setback was a disappointment to women’s suffrage supporters, they could be proud that Rhode Island was the first eastern state to even consider and vote on a women’s suffrage referendum.

The defeat, while painful to accept, did not deter the suffragettes. After all they had been laboring for nearly forty years for suffrage reform and setbacks were nothing new to them. In fact, it would be nearly another thirty years before they would attain their goal. For the remainder of the 19th century the members of the RIWSA would labor to change public opinion of not only the male electorate but also of the many women who still opposed female suffrage.

By the time the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, all the early leaders in the women’s rights movement had passed from the scene. National leaders lasted longest. Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902 and Susan B. Anthony in 1906, each at age 86. Rhode Island’s Paulina Wright Davis died in 1876 (age 63) and Elizabeth Buffum Chace in 1899 (age 93). It is unfortunate that none of these women’s suffragette leaders lived to see the fruit of their labors. In our American democracy change does not come easily but it eventually does come. Unlike at the beginning of the 19th century when it was unthinkable for women to vote, today it is equally unthinkable for women not to vote.

[Banner image: Masthead of the newspaper The Una – Volume 1 No. 1 (Russell DeSimone Collection)]

Notes

[1] Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, The Devotion of These Women, Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), 25. [2] The list is set forth in Appendix C in Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004). [3] Thomas Davis (1806 – 1895) was an Irish born naturalized United State citizen having come to America as a boy. He was a successful jewelry manufacturer in Providence. He served one term (1853 – 1855) as U.S. Representative for the Eastern District of Rhode Island. From 1845 to 1853, and again from 1877 to 1878, he was a state senator in the Rhode Island General Assembly, and from 1887 to 1889 he served as a state representative from Providence. [4] The Una was first published in Providence in February 1853. The publication moved to Boston where it continued to be published until October 1855. [5] For a detailed account of women nurses at Lovell Hospital see Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital – Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove, 1862 – 1865 (McFarland, 2012), especially chapter 11, titled Angels of Mercy. [6] Edwin Stone, Rhode Island in the Rebellion (George H. Whitney, 1864), 392-393. [7] Providence Evening Press, April 3, 1873. [8] Woodhull’s running mate was said to be the former slave and abolitionist Fredrick Douglass. However, Douglass never agreed to accept the nomination and in fact stumped for President Grant. Often overlooked was that Woodhull was just 34 years old, too young to meet the constitutional age requirement to be president. [9] See Christian McBurney, “Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910),” in his article “The Greatest Rhode Islanders of All Time: Counting Down from Number 10 to 6,” (April 22, 2017), on www.smallstatebighistory.com. [10] Newport Daily News, April 9, 1887.