This 2014 essay, inspired by my penchant for observing historical anniversaries, was written as a Providence Journal commentary. It came to the attention of Professor Stephen Schechter, who was preparing a five-volume set of essays entitled American Governance. When I chaired the U.S. Constitution Council during the bicentennial of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, Steve was the Council trustee from New York.

I supplied this essay for his encyclopedia project while suggesting that it be expanded to discuss the 1647 Code of Laws enacted under the authority of the patent. I also furnished, at Steve’s request, a brief analysis of Rhode Island’s Royal Charter of 1663.

According to Webster’s Third International Dictionary, a patent is “an official document issued by a sovereign power conferring a right or privilege;” whereas a charter is an instrument in writing from the sovereign power granting or guaranteeing rights, franchises, or privileges, and creating and defining the franchises of a city, university, [colony], company, or other private or public corporation.” From those definitions and the Rhode Island experience, it appears that a main difference between the two instruments is that a charter was more specific and dealt with governance in much greater detail.

These essays are reproduced herein not only because they are succinct descriptions of Rhode Island’s founding documents, but also because they might be obscured in Steve’s large (and very valuable) project. In 2016 American Governance was completed. It is available from Gale Publishing at the modest price of $700.

*****************************************

Providence, the first settlement in what would soon become the colony of Rhode Island, was founded at the head of Narragansett by Roger Williams in the spring of 1636. Williams, an outcast from the colony of Massachusetts Bay established his settlement on the basis of religious (or “soul”) liberty and separation of church and state by obtaining deeds from the Narragansett tribal sachems, Canonicus and Miantonomi. Williams’s radical religious beliefs and his affirmation of the land rights of Native Americans were the basic causes of his banishment.

While Providence was still in its infancy the Narragansett region became the refuge of other nonconformists. In 1638, a group of religious exiles, mostly Antinomians, led by William Coddington, established the community of Portsmouth on the northern tip of the island of Rhode Island (called “Aquidneck” by the natives) on land which they had purchased from the Indians through the intercession of Roger Williams. The outcasts of Portsmouth, in Biblical fashion, elected Coddington “Judge” of their little community.

It was evident from the outset, however, that the forceful Coddington did not share Williams’s concern for the absolute separation of church and state. For this and other reasons Antinomian leader Anne Hutchinson, Samuel Gorton, and other disgruntled settlers staged a coup against Coddington and deposed him in April 1639. Undaunted, Coddington led his followers to the southern end of the island where he established the settlement of Newport. Here he was chosen “Judge” with a double vote.

Although Coddington had been bested he was not beaten, for within a year he had cleverly engineered a consolidation of the two island towns under a common administration of which he was governor. This new political entity proclaimed itself a democracy on March 16, 1640/41 and guaranteed religious liberty to all. Because title to the entire island of Rhode Island (i.e., Aquidneck Island) was in his name, Coddington began to entertain thoughts of creating a domain of his own distinct from the Providence Plantation. This ambitious plan constituted the most serious internal obstacle to the creation of a united colony during Rhode Island’s formative years.

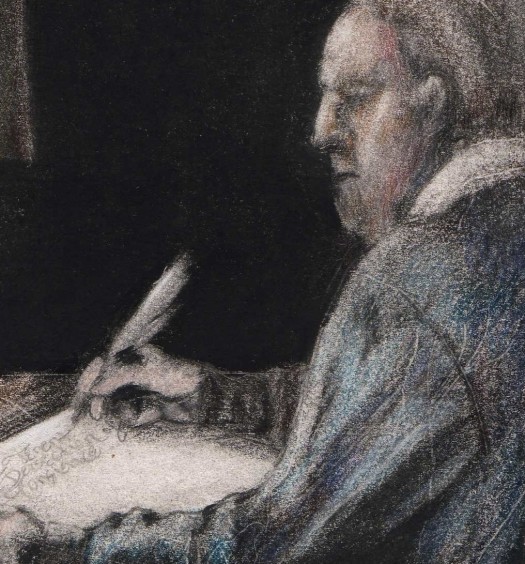

![[Banner image: Roger Williams, returning to Providence from London in 1644, holds up the Rhode Island Patent of 1643-44. By E. Boyd Smith (1860-1943) (New York Public Library)]](http://smallstatebighistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/RogerWilliamsBringingCharter1644.jpg)

Roger Williams, returning to Providence from London in 1644, holds up the Rhode Island Patent of 1643-44. By E. Boyd Smith (1860-1943) (New York Public Library)

The patent, dated March 14, 1643/44, was the first legal recognition of the Rhode Island towns by the mother country. It authorized the union of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport under the name of “the incorporation of Providence Plantations in Narragansett Bay in New England,” and it granted these towns “full power and authority to govern and rule themselves” and future inhabitants by majority decision, provided that all regulations that were enacted were “comformable to the laws of England” so far as the nature of the place would permit. This initial patent specifically conferred political power upon the inhabitants of the towns. The repeated emphasis of the document upon “civil government” gave implicit sanction to the separation of church and state, whereas the use of words “approved and confirmed” rather than “grant” in conjunction with the right to the land was a vindication of Williams’s contention that the Indian deeds were valid. Williams’s adroitness and diplomacy had won the day, and he was greeted with great enthusiasm when he returned to Providence, patent in hand, in September 1644.[1]

While Williams was in England, volatile Samuel Gorton, a free-thinking man with a proclivity for disputation and passion for the common law, had succeeded in developing a mainland settlement to the south of Providence which he eventually called Warwick in honor of the earl (hoping, no doubt, to curry favor with the powerful aristocrat). Here, as in Providence, liberty of conscience prevailed. Although his new settlement was not mentioned in the patent, the beleaguered Gorton sought and eventually secured inclusion of his town under its protective provisions.

The two island towns of Portsmouth and Newport also embraced the legislative patent and representatives of the four communities met initially on Aquidneck Island in November 1644. After this and three subsequent sessions, they held the momentous Portsmouth Assembly of May, 1647 to organize a government and to draft and adopt a body of laws. According to Charles McLean Andrews, one of the leading historians of colonial America, “the acts and orders of 1647 constitute one of the earliest programmes for a government and one of the earliest codes of law made by any body of men in America and the first to embody in all its parts the precedents set by the laws and statutes of England.”[2]

The assembly that drafted this code was attended by a majority of the freemen of the four towns. The delegates agreed that they were “willing to receive and to be governed by the laws of England together with the way of Administration of them, so far as the nature and constitution of this plantation will admit.” However, they further declared that the form of government for the colony was “democratical” in that it rested on “the free and voluntary consent of all, or the greater part of the free inhabitants.”

At this landmark 1647 assembly, officers were elected, a system of representation established, and a legislative process–containing provisions both for local initiative and popular referendum–was devised. Then the delegates enacted the remarkable “code,” an elaborate body of criminal and civil law prefaced by a brief statement of protections. First and foremost among these was the assertion, derived from the Magna Carta, that “no person . . . shall be taken or imprisoned or be disseized of his Lands or Liberties, or be Exiled, or molested . . . or destroyed, but by the Lawfull judgment of his Peeres, or by some known Law, and according to the Letter of it, Ratified and confirmed by the major part of the Generall Assembly lawfully met and orderly managed.”

According to the “laws and orders” of 1647, accused criminals were to be indicted by a grand jury of “twelve or sixteen honest and lawful men” and tried by a separate jury of 12 empowered to hear and determine all “controversies and differences . . . between partie and partie.” The members of this petit jury were to receive “a solemn charge” from the trial’s presiding officer, “upon the perill and penaltie” of the law, “to do justice between the parties contending, according to the evidence.” At trial’s end, that officer was to remind the jury of the “most material passages and arguments” brought be each side “without alteration or leaning to one party or another.” Thereupon the jury was “to goe forth and do justice and right between their neighbors.”

It is important to note that in colonial times the right of trial by jury was regarded as a right belonging not only to the accused but also to the citizen as juror. In Rhode Island only freemen (i.e., voters) were eligible to serve on juries. Until 1827 these select citizens decided both the law and the facts in every case and exercised a strong popular check on judges, administrators, and lawmakers alike.

Under the legal code of 1647, defendants in criminal trials were allowed preemptory challenges against as many as 20 prospective jurors. They could plead their own case, select a personal attorney to defend them, or “use the Attorney that belongs to the Court.” The only caveat was that such “pleader or attorney” shall not “use any manner of deceit to beguile either Court or partie.”

Finally, for the administration of justice, the productive 1647 assembly established a General Court of Trials having jurisdiction over all important legal questions. The president, who was the chief officer of the colony, and the assistants representing their respective towns, were to comprise this high tribunal. By inference, the existing town courts were to possess the jurisdiction heretofore exercised in matters of minor and local importance. The code and the court system of 1647 served as the cornerstones of the judicial establishment of Rhode Island both as colony and state. Thus did the four original towns and their inhabitants combine to create a fairly systematized federal commonwealth and deal a paralyzing blow to the forces of decentralization.

[Banner image: Roger Williams, returning from London in 1644, holds up the Rhode Island Patent of 1643-44. By E. Boyd Smith (1860-1943) (New York Public Library)]

Bibliography

[1] Chapin, Howard M., ed., Documentary History of Rhode Island (Providence: 1916-19), 1:214-17. This contains the British Sate Paper Office copy of the patent, which is the most accurate draft. [2] Andrews, Charles McLean, The Colonial Period of American History (New Haven, CT: 1934-38), 2:26.