In the afternoon of June 9, 1772, the sloop Hannah, a Providence packet commanded by Capt. Benjamin Lindsey, sailed forth from Newport up Narragansett Bay toward its home port. Very quickly Lindsey discovered that he was being chased by the Gaspee, a British revenue schooner stationed in the bay “for the protection of the Trade, and to prevent smuggling.”

The Gaspee and its commander, Lieutenant William Dudingston, were well known and well hated by Rhode Islanders. So extreme had been Dudingston’s efforts to enforce maritime regulations and to collect duties owed the Crown, and so insolent and overbearing had he and his crew been in their treatment of merchants, seamen, and farmers alike, that Governor Joseph Wanton had already protested vigorously to Dudingston and to his superior officer, Admiral Montague in Boston, and the General Assembly in May had directed the governor to write to London about his “wanton and arbitrary manner.” But these protests had been in vain, and now Dudingston was determined to force the Hannah to submit to search. “Crowding on all the Sail she could make,” the Gaspee pressed the pursuit, but about three in the afternoon she ran aground on Namquit Point, near Pawtuxet. With the tide already at the ebb, she would have to wait until well after midnight before she could float free.

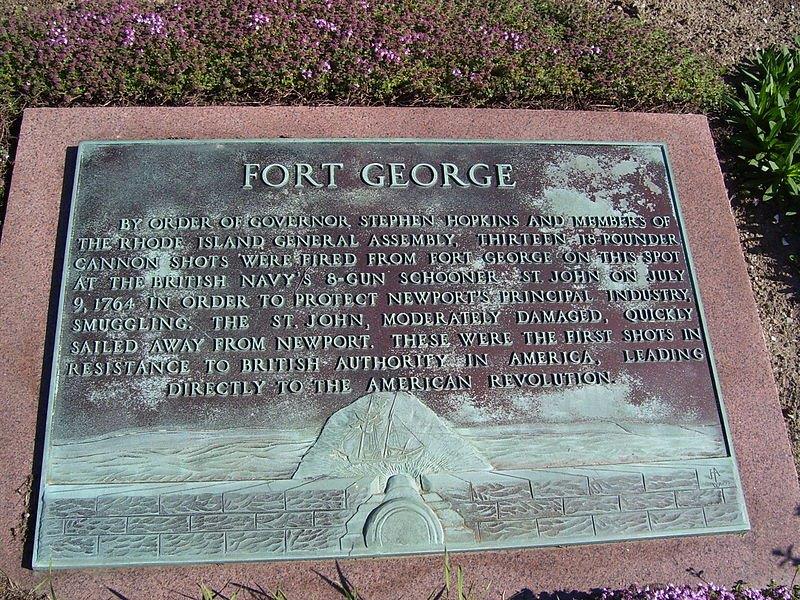

Plaque on Goat Island, explaining the role of Fort George in firing cannon at the British Navy vessel St. John (at the orders of Governor Stephen Hopkins) and driving it away from Rhode Island smugglers.

Captain Lindsey sailed on to Providence to carry the news directly to John Brown, one of the great merchants whose trade had been annoyed by Dudingston.

Determined to destroy the Gaspee, Brown gathered a force of men by beat of drum and embarked with them about ten at night in eight long boats. With muffled oars they moved silently down the bay toward the helpless Gaspee. Although detected in their approach, they captured and burned the ship after removing the crew to the shore, the only man injured being Lieutenant Dudingston who was shot in the groin. One Rhode Island historian, Samuel Greene Arnold, asserts that “this was the first British bloodshed in the war of independence.”

The consequences of the burning of the Gaspee were such that to consider it the starting point of the American Revolution may well be justified. Governor Wanton issued a proclamation urging all officers to seek out and apprehend the guilty parties, and offered a reward of one hundred pounds, sterling, for .the conviction of any one or more of the “perpetrators of the villainy.” But this was mere facade, for despite the many persons involved, and the widespread public knowledge of the event, not a single participant was ever brought to trial by Rhode Island officials.

Burning of the Gaspee in 1772. Gaspee Magic Lantern Slide, Artist Unknown. Purchased in Scituate by John Concannon.

In August, however, George III ordered that a Royal Commission investigate the incident on the grounds that it was an act of “high treason, viz.: levying war against the King.” Offenders were to be delivered into the custody of the commander in chief, of the British Navy in America to be carried to England for trial. If necessary, the Commissioners could call upon General Gage in Boston for troops to preserve the peace. A royal reward of five hundred pounds was offered for the capture of any persons who had attacked the Gaspee and a reward of one thousand pounds and complete pardon for any accomplice who would betray the leaders and the person who had shot Dudingston.

The Gaspee being set on fire by Rhode Islanders in small boats, one of the outstanding acts against British imperial rule before the commencement of the Revolutionary War (Frank Merrill, 1918)

Although Governor Wanton was a member of the Commission and the powers of the Commission were limited to investigation with no power to arrest except through warrants issued by the local courts, the people of Rhode Island were shocked. Ever since the founding of the colony they had governed themselves with little regard for English power, turning to the Crown generally only when in need of help against the surrounding colonies or a foreign enemy. In fact, the liberal terms of the Charter of 1663 seemed to guarantee them such freedom to control their own affairs, including the right to try offenders against the Crown in their own courts before their own juries, punishing them or setting them free as they saw fit.

Now, in sharp contrast, as pointed out by the Providence Gazette, the Crown had authorized the transporting of suspects three thousand miles “at the points of bayonets” and “Americans” in the Newport Mercury contended that “this new-fangled court” was more “horrid” in its “exorbitant and unconstitutional power” than any in Spain or Portugal. The editors of the two papers urged that “Americans and freemen ought never to acquiesce,” and that, in “a truly Roman spirit” they should unite to “prevent the fastening of the infernal chains . . . or nobly perish in the attempt!”

Such alarm over the creation of the Commission is not to be wondered at, for in the past the virtual independence of Rhode Island had meant that it had been possible within the colony for the authority of royal officials to be frustrated and. for the property of the Crown to be destroyed with almost certain immunity from punishment.

The events of the past decade had given repeated proof of this blessing of self-government. In January, 1764, John Temple, Surveyor General for the Crown, had ordered the ship Rhoda seized in Newport harbor for violation of the acts of trade. Two days later, after sundown, she was sailed off “by Persons unknown,” and although he offered a reward Temple never learned who the guilty men were.

That same year the crew of H.M.S. St. John aroused the wrath of Newporters by stealing hogs and poultry. Tempers flared, and the gunner at Fort George, with authority granted by members of the colony Council, opened fire on the schooner. Although he intentionally missed, and ceased firing before the ship could reply, the insult to Crown and Royal Navy was obvious and deeply resented by the officers of the naval vessels in the harbor. Their protest to the colony officials went unheeded; in fact, the Council members, when Gunner Niughan appeared to make his report, wanted to know only why he had failed to sink the St. John.

In 1765 the Maidstone, another ship of the British navy, became the object of Newport’s anger. For months its crew operated the “hottest Press ever known” in the town in an effort to obtain a sufficient number of sailors to fill out its complement. The threat of impressment became so great that wood boats, fishing vessels, and coastal schooners, all avoided the port and seamen’s wages rose sharply.

On June 4 the Maidstone’s officers impressed the entire crew of a brigantine just arrived from Jamaica. A mob of five hundred seized one of the Maidstone’s boats, dragged it to the upper end of town, and burned it, at the same time fiercely threatening one of the ship’s officers. No blood was shed; however, and the riot ended without further destruction of property. The indignant protest of Captain Charles Antrobus gained no more satisfaction from Governor Samuel Ward than had been received from Governor Stephen Hopkins the year before: no Rhode Islander suffered punishment or even rebuke for this affront to the navy, and, in fact, Antrobus was finally forced to release all the Rhode Island sailors he had held on his ship.

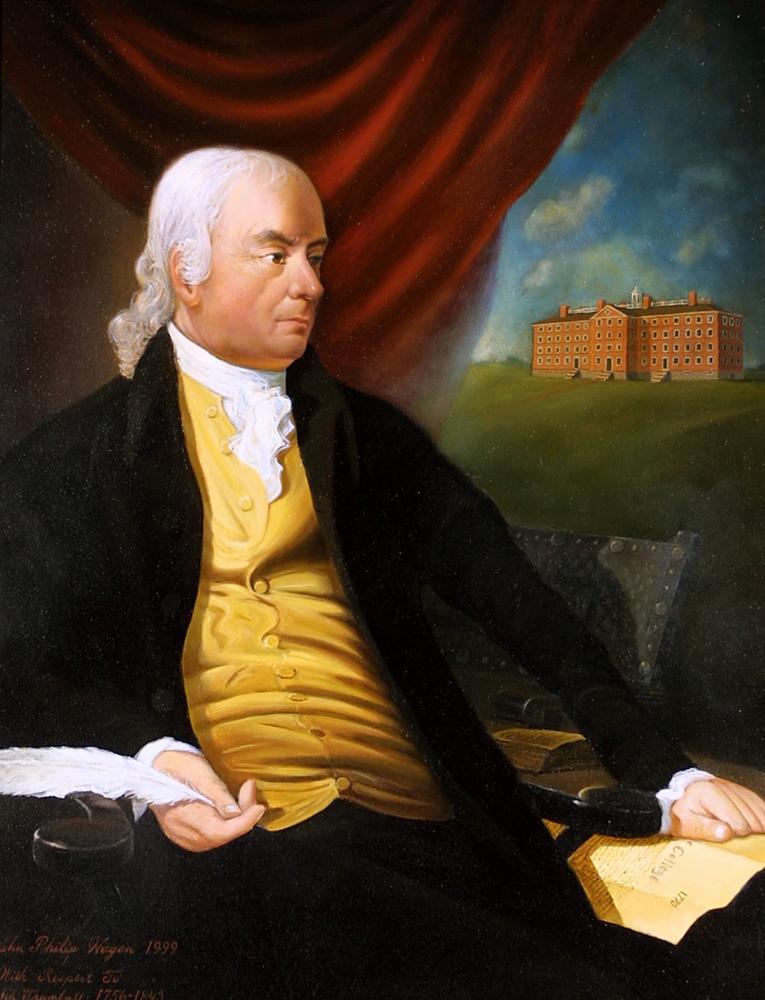

Stephen Hopkins, leader of a political faction centered in Providence, served as governor numerous times and was selected as a delegate to the first two Continental Congresses in Philadelphia, and signed the Declaration of Independence (Brown University Portrait Collection)

Late in August, 1765, there occurred another incident proving the value of self-government to Rhode Island. In March, Parliament had adopted the Stamp Act, requiring that practically all legal documents, college diplomas, business papers such as leases and contracts and bills of sale, playing cards, dice, almanacs, newspapers, and pamphlets must be written or printed on paper carrying a stamp embossed by the Treasury Office. The tax ranged from ten pounds down to one shilling, dependent upon the use to which the paper was to be put. The paper had to be paid for in sterling, not in colonial currency, and the money thus raised was to be used to provide supplies for British troops stationed in the colonies. Violation of the Stamp Act, at the election of the prosecutor, could be tried in the admiralty courts which operated without juries. The measure was thus obnoxious in every respect, for it taxed all classes of people without their consent for the purpose of raising revenue to maintain troops which could be used or controlling the colonies, and it enlarged the jurisdiction of the admiralty courts, dependent solely on the Crown, and thus abridged the rights of the people to common-law trials.

Protests against this measure took a variety of forms, including massive riots in a number of cities, Newport among them. The example was set in Boston in mid-August. The mob there had destroyed a shop belonging to Andrew Oliver, appointed to distribute stamps in Massachusetts, and wrecked his house, forcing him to resign. William Story, an officer of the Admiralty court, Benjamin Hallowell, the chief customs officer, and most important of all, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, had also suffered the destruction of their houses. The message intended by the organizers of the mob, that the Stamp Act should not be enforced in Boston, was made abundantly clear. News of the Boston events suggested a similar course of action to Newport opponents of the Stamp Act. On August 27 Augustus Johnston, who had been appointed Stamp Distributor for Rhode Island, and Martin Howard, Jr. and Dr. Thomas Moffat, outspoken supporters of royal authority, were hung in effigy. The next day the mob destroyed the houses, of Howard and Moffat, pillaged Johnston’s house, and forced him to resign his post as Stamp Master. Throughout the rioting Governor Samuel Ward remained discreetly at his farm in Westerly, and upon his return to Newport blandly assured Collector John Robinson, who had taken refuge on the man-of-war Cygnet in the harbor, “that everything is perfectly tranquil, and that you may immediately return to town with all the safety imaginable” As in Boston, not a person was ever punished for the instigation of the riots or for the destruction of property. November first, the effective date for the Stamp Act, came and went in both ports without a single piece of stamped paper purchased and used as required by the law.

Still another incident demonstrating the limited force of royal authority in Rhode Island occurred in 1769. Acting under the directions of the Collector of Customs, Charles Dudley, and the Board Hof Customs, His Majesty’s armed sloop, Liberty, commanded by Capt. Reid, arrived in Newport in May. The next day the Liberty seized a Providence vessel for illegal importation of molasses, indicating Capt. Reid’s intention of rigorous enforcement of the laws. In July the Liberty brought two Connecticut vessels into Newport, and in plain view of the townspeople on the wharves, fired upon one of the Connecticut captains when he protested the treatment accorded him and his crew. That evening an infuriated mob, finding Captain Reid on shore, forced him to remove his crew from the Liberty and then seized and grounded the ship and cut down her masts. A few days later she was scuttled and burned. The mob, meantime, had dragged the Liberty’s boats into the town and burned them with great excitement. The two Connecticut prizes, of course, during this confusion made good their escape. At the behest of Dudley, Collector of Customs, Governor Wanton issued a proclamation calling for the arrest of the persons responsible, and a reward of one hundred pounds was offered by the Board of Customs in Boston, but as usual, no arrests were made.

Two years later Dudley was set upon by persons unknown and seriously injured. For a. time it seemed that his life was in danger. Again despite the protests of the Earl of Hillsborough, no action was taken. In fact, Governor Wanton blandly blamed the whole affair upon Dudley who had shown such poor judgment as to board a vessel “in the dead time of the night, singly and alone,” where he fell prey to a number of “drunken sailors.” Wanton then proceeded to complain bitterly about British officials who falsely accused and misrepresented the loyal and law-abiding people of Rhode Island. In making this protest, Governor Wanton ignored completely other incidents such as the attack in 1769 by an angry mob in Providence upon Jessie Saville, Dudley’s deputy. Saville had been beaten almost to death because of his efforts to enforce the customs laws, but no one had been punished for the deed. The life of the British official who sought to enforce the laws regulating and taxing commerce in Rhode Island was a hazardous one unless he chose to cooperate with the merchants—and then he might live peacefully and comfortably upon the bribes paid him.

In fact, until the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, commerce had been expanding and growing more prosperous, and relations between Rhode Island and the mother country had been quite harmonious. Relatively few laws affecting Rhode Island commerce had been adopted by Parliament, and those that did were either ignored completely or sufficiently modified in execution to be harmless.

In 1763, however, George Grenville became prime minister of Great Britain. With peace established by defeat of the French, he determined to relieve the English people of some of the burden of taxation they would otherwise have to bear by rigid enforcement of existing customs and by the imposition of new taxes on the American colonies. At the same time he hoped to make the colonies serve imperial interests more fully than they then seemed to be doing. Accordingly, he ordered customs collectors to do their duty in person rather than through ill-paid deputies susceptible to bribes, and he directed the Navy to patrol the American coast to seize smugglers.

In 1764 Grenville secured from Parliament passage of the Sugar Act, altering colonial import duties and stiffening provisions for enforcement. The measure aroused vigorous protests in America. Not only did it specifically avow the Ministry’s intent to raise by taxes on colonial trade revenue for the maintenance of troops in America, but violators of the law could be prosecuted before the courts of admiralty, without a jury. New duties, such as that on Madeira wine, would destroy the profitable trade with the Azores, and reduction of the duty on foreign molasses from 6 d. to 3 d. a gallon, with the tax actually collected, would injure seriously the many-sided and flourishing trade built on molasses. Rhode Island merchants exported fish, meat, butter, cheese, horses, furniture, lumber products, and other items to the West Indies. There they obtained specie, bills of exchange, dyewoods, sugar, and most important, molasses, which they brought back to Newport to distill into rum. But the British sugar islands could provide only about one-fifth of the molasses they needed; the remaining four-fifths came from the French islands. If the three pence tax were actually collected, the cost of rum would be so increased as to render unprofitable the trades in which it was used, such as the African slave trade. And if the trade with the West Indies were curtailed, and the distilleries forced to close, and the African trade disrupted, not only the merchants but the entire colony would suffer, for it would then have no means of earning the sterling exchange necessary for purchase of British manufactures.

Already suffering from a post-war depression, the colonists could see nothing but evil in the Sugar Act. The Rhode Island General Assembly had protested against the measure to the Board of Trade before it was enacted by Parliament. When it became law, Governor Stephen Hopkins in a pamphlet endorsed by the General Assembly, The Rights of Colonies Examined, reviewed again all the economic objections to the law but in addition asserted that the stamp act that had been proposed along with the Sugar Act but adoption of which had been postponed for a year, was a “manifest violation of their [the colonists] just and long enjoyed rights.” Men “who are taxed at pleasure by other, cannot possibly have any property; can have nothing to be called their own; they who have no property can have no freedom, but are indeed reduced to the most abject slavery.” The General Assembly also sent its own petition to the King, urging that the new laws be rescinded and that the colonists might not be taxed “but by the consent of their own representatives, as Your Majesty’s other free subjects are.” The protests of Rhode Island and the other colonies availed nothing, however; the Sugar Act remained in force and the Stamp Act was adopted in 1765.

Not only did Rhode Island make its opposition to this measure known through the newspapers and riots, but the General Assembly in September adopted a set of resolutions modeled upon those adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses under the leadership of Patrick Henry. In clear, sharp language the Assembly claimed for the people of Rhode Island all the rights of Englishmen, noted that they were guaranteed by the charter and confirmed by over a century of practice, and declared that the “Inhabitants of this Colony, are not bound to yield Obedience to any law or Ordinance, designed to impose any internal taxation whatsoever upon them, other than the Laws or Ordinances of the General Assembly. . . .” Finally, the officers of the colony were “directed to proceed in the Execution of their respective Offices, in the same manner as usual; And that this Assembly will indemnify and save harmless all the said Officers, on Account of their Conduct, agreeable to this Resolution.” Thus was resistance officially endorsed.

One result of this Assembly action was that the courts of Rhode Island stayed open without interruption, the only colonial courts to thus ignore completely the requirements of the Stamp Act. This affront to British authority was made even more emphatic by the serve temporarily as the King’s attorney in the place of Augustus Johnston. Johnston had been appointed. Stamp Distributor; although he had resigned under pressure from the Newport mobs, he chose to absent himself from court sessions. Downer, appointed to replace him, was the Corresponding Secretary of the Providence Sons of Liberty, the organization into which the haters of the Stamp Act had gathered!

In October, responding to the call of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, Rhode Island sent Metcalf Bowler and Henry Ward to the Stamp Act Congress in New York. The Resolutions adopted by that body and the petitions sent to King, Lords, and Commons declared that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and that the extension of the jurisdiction of the Admiralty courts was, a denial of their “inherent and invaluable right” of trial by jury. When the Rhode Island delegates returned home they submitted a written report including a copy of the proceedings of the Congress to the General Assembly meeting in South Kingstown. The Assembly without hesitation accepted the report and ratified the declarations and addresses of Congress.

Meantime even more significant opposition to the Stamp Act developed in the form of non-importation agreements signed by the merchants of New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Salem, and other ports. As trade between England and America came to a halt, the London merchants petitioned Parliament to repeal the offensive measure. In March, 1766, they won their point, for the Stamp Act was dropped completely. But for the colonies the victory was only a partial one, as Parliament coupled with the repeal of the Stamp Act a sweeping declaration of its power “to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, . . . in all cases whatsoever.” In the joy of the moment, however, the latter was overlooked, and massive celebrations were held in Newport and Providence in-May, and June, 1766. The noise of drums, bells, and cannon; display of flags; skyrockets and other fireworks; patriotic sermons; the drinking of toasts in almost endless number (Providence managed thirty-four!) — all combined to make clear the rejoicing of the Rhode Islanders.

The very next year Parliament adopted the Townshend duties on glass, lead, painters’ colors, tea, and paper, and established American Commissioners of Customs to reside in Boston to stiffen enforcement of the acts of trade. Further aggravation came in the creation of four new courts of Vice-Admiralty at Halifax, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charlestown. There had been one at Halifax for a number of years, but distance had made it only a limited threat. A court in Boston, operating right under the eyes of the Customs Commissioners, would be quite a different story. Rhode Island violators of the Navigation Acts and customs laws could henceforth expect their cases to be carried before the Boston court rather than before the friendly Rhode Island admiralty court.

Again Rhode Island made formal protest in a petition to the King and then voted approval of the Massachusetts House of Representatives’ Circular Letter condemning the taxes. The newspapers were filled with discussions of the rights of the colonists and, when merchants in other, colonies resumed non-importation, with exhortations to the public to “Save your money, and Save your Country.” In an effort to encourage domestic industry the Newport Mercury offered free advertising to local weavers.

Rhode Island merchants were slow to cut off importation of British goods, but under pressure from the local populace and from other ports which refused to trade with them, finally joined in the general boycott. Again Parliament succumbed to the pleas of London merchants whose American trade fell by £700,000 in 1769, and in 1770 repealed all the Townshend duties with the exception of that on tea, retained, in Lord North’s words, “as a mark of the supremacy of Parliament, and an efficient declaration of their right to govern the colonies.”

This second victory over Parliament, although not complete, was followed by a period of general peace in imperial relations and widespread prosperity in the colonies. But in Rhode Island the enforcement of the long-standing Navigation Acts and of the recent Sugar Act provided frequent irritation, culminating in the. Gaspee incident in 1772. The appointment of the royal commission to investigate did far more than rouse Rhode Island.

In March, 1773, the Virginia House of Burgesses adopted resolutions challenging the legality of the Gaspee commission and appointed a Committee of Correspondence to obtain information about the actions of Parliament relating to the colonies and to maintain communication with the other colonies. Rhode Island and most of the other colonies followed suit.

In Rhode Island the Committee of Correspondence was comprised of Stephen Hopkins, Moses Brown, Henry Marchant, and Henry Ward, men who had been outspoken in defense of the rights of the colonists. The appointment of these committees, providing a framework for cooperation, placed the American colonies in a position of readiness for the next events in the struggle for the renewal of the freedom in self-government they had known prior to 1763.

The next move toward rebellion came in response to the adoption, by Parliament in May 1773, of the Tea Act. Designed to save the East India Company from bankruptcy, it permitted that company to sell tea directly in America, without payment of the tax normally imposed on the tea when imparted into England. The only tax on the tea would be the three penny tax fixed by the Townshend Acts. The tea would thus cost less than in England, but its sale would now be entirely in the hands of the agents of the East India Company.

The combination of monopoly and apparent bribe to pay the Townshend duty peacefully brought forth diverse protests from the colonists. Most widely reported was the Boston Tea Party in. December, 1773, but in Newport three hundred families pledged themselves not to use the beverage, and many towns in Rhode Island adopted resolutions and chose Committees of Correspondence against the Tea Act. South Kingstown, contending that the intent of Parliament was that the Tea Act should be a precedent for the establishment of “taxes and monopolies upon all the necessaries of life in America,” pledged that it would “neither buy, sell, nor receive upon any conditions whatever, any dutied Teas,” and promised to “heartily unite” in defense of the rights of the colonists. Not a voice was raised in Rhode Island in support of Parliament and the Tea Act.

Parliament in 1774 responded to colonial defiance of the Tea Act by adoption of the Coercive Acts, closing the Port of Boston until the tea cast into the harbor was paid for, and altering the government of Massachusetts to strengthen the authority of the royal governor. The freemen of Providence a few days after learning of the Port Act resolved in town meeting that it was a “stroke aimed at us all,” and urged that all trade with England be immediately stopped. In addition, they proposed a general congress of all the colonies to consider further “opposition to the Unrighteous Impositions.” The Newport Town Meeting promised the cooperation of that town in cessation of trade. And thus from throughout the colony came clear indications of support for firm action, and one community after another sent food or money to aid the beleaguered inhabitants of Boston during the following months.

When the General Assembly met in June it quickly adopted the idea of an inter-colonial congress and selected Stephen Hopkins and Samuel Ward to represent Rhode Island. They were instructed to work for a “regular, annual convention of representatives from all the colonies” which would give continuing attention to “proper means for preservation of the rights and liberties of the colonies.” In the First Continental Congress held in Philadelphia in September, Ward took the radical position that Parliament had no power whatsoever to regulate the trade of the American colonies. The Congress, however, refused to go that far, and instead sought merely the repeal of those measures adopted by Parliament since 1763. To compel Parliament to accede to this demand, the Articles of Association were adopted, providing for complete non-importation to be enforced by local Committees of Inspection. When Ward and Hopkins returned to Rhode Island in. November, the Assembly distributed copies of the Articles of Association to all the towns; and before long local committees were at work zealously enforcing the economic boycott of England.

During the winter of 1774-1775 the spirit of resistance took on even more extreme forms. The Newport Mercury suggested that only the “American Independent Commonwealth” could protect the rights of the people from “rapacious and plotting tyrants.” The Providence Gazette contended that if a ruler acted in a manner destructive of the rights of the community, the people are “discharged either from active or passive obedience, and indispensably obliged by the law of nature to resistance.” Numerous independent military companies were chartered by the Assembly, and the members trained faithfully. Kent County reported that it had 1,500 men equal to the best of the King’s soldiers. The Assembly revised the militia laws of the colony, and authorized the troops to march to the aid of any neighboring colony that might be attacked. Though an occasional Tory voice was heard, Rhode Island seemed ready for even more active defense of its traditional freedom.

When the fatal shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Rhode Island responded immediately. An emergency session of the Assembly three days later voted to raise an army of observation of 1,500 men. to “repel any insult or violence” to the people of the colony and to join with the forces of other colonies if necessary. Because governor-elect Joseph Wanton sought to prevent the act from going into effect by refusing to take his oath of office and to sign the commissions of officers, the Assembly stripped him of his powers and then removed him from office. In his place the Assembly elected Nicholas Cooke, a tough-minded patriot who was determined that Rhode Island should play its full part in the rebellion. And that it did. Names such as Nathanael Greene, Esek Hopkins, James Varnum, and many others attest to that fact. The rights, the freedom to govern their own affairs that the people of Rhode Island had known since the earliest days of the colony were precious enough to deserve the best they had to offer in their defense.

A few years before the war, Nathanael Greene was a virtual unknown. But he was selected by the General Assembly to serve as brigadier general of the Rhode Island troops sent to participate in the siege of Boston. Greene quickly became a favorite of George Washington’s, and grew into perhaps the best field commander of the entire Revolutionary War (Independence Hall)