The centenary of the 1920 ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (the so-called Susan B. Anthony amendment) is fast approaching and as such there is renewed interest in the history of the women’s suffrage movement. Rhode Island has had its share of female leaders in this cause. The first wave of suffragists included such notables as Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Paulina Wright Davis and Julia Ward Howe, all of whom lived or spent considerable time in the state. As the woman suffrage movement took a full seven decades before it reached its goal, it’s understandable that a second wave of suffragists was needed to come to the fore and replace the first-generation leaders who were silenced by advanced age or death. Counted among this new wave of women were Rhode Island’s Lillie Chace Wyman, Maude Howe Elliot, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Sara Algeo. Two unheralded women suffragists who resided in Rhode Island need to be considered as worthy of inclusion in this second-generation of reformers. They were Maria Kindberg and Ingeborg Kindstedt. While they were recent immigrants to America, they would play a significant role in one of the most publicized events in the suffrage movement of the 20th century.

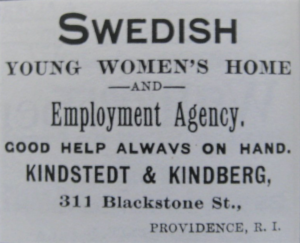

Maria Albertina Kindberg was born in Ryd near the town of Skövde, Sweden, on October 12, 1860; she arrived in the United States on June 25, 1889. Maria Ingeborg Kindstedt was born in Glava near the town of Karlstad, Sweden, on April 8, 1865; she arrived in the United States in October 1890.[1] Since these two towns are nearly one hundred miles apart, it is unlikely that the Swedish immigrants knew one another before arriving in America. It is also unclear how they met or where they lived until 1895 when their names first appeared in the Providence Directory. The directory shows them living together at 311 Blackstone Street in the South Providence section of the capital city. At that time South Providence was home to numerous immigrant groups, including an enclave of Swedes with a Swedish church conveniently located nearby. Maria was listed as a midwife, while Ingeborg appeared as a lecturer. Soon they were advertising a Swedish Home for Young Women, as well as an employment agency (figure 1).

The woman suffrage movement in the United States had always been fractured by factions and rival organizations. The first great split occurred in 1869 when the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted African American men the right to vote, was first proposed. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted the amendment to include women while other suffragists led by Lucy Stone, her husband Henry Blackwell, Rhode Island summer resident Julia Ward Howe, and others, supported passage of the amendment as framed. The Anthony-Stanton group formed the National Woman Suffrage Association opposing passage of the amendment, while those favoring passage established the American Woman Suffrage Association. It would not be until 1890 that these two rival organizations reconciled and merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

The Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association (RIWSA) was formed in 1868 under the leadership of Paulina Wright Davis and Elizabeth Buffum Chace. By the early 20th century there were other organizations in existence that also favored women suffrage. In 1907 the College Equal Suffrage League was formed; in 1909 Newport summer resident Alva Vanderbilt Belmont led the formation of the Political Equality League; and across the state leagues were formed, mostly as auxiliaries of the NAWSA. In 1913 the Rhode Island Women’s Suffrage Party (RIWSP) was established and by 1915 the RIWSA, the College Equal Suffrage League, and the RIWSP were all encompassed as The Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association under the leadership of Agnes Jenks.

Alice Paul and Lucy Burnes, two women greatly influenced by the more militant British woman suffrage movement, formed yet another organization, the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), in April 1913. Paul and Burns had been members of the NAWSA’s Congressional Committee, but they differed on strategy. The NAWSA had sought to achieve women’s suffrage by focusing on individual state voting rights, while the CU focused on a federal constitutional amendment. Two years later the CU would evolve into the National Woman’s Party. It was during this period of renewed effort to gain women’s suffrage that Maria and Ingeborg first appeared on the scene as suffragists.

The earliest accounts of Maria’s and Ingeborg’s involvement in the suffrage movement is found in the newspapers of the day. By 1914 accounts of meetings of the Woman’s Political Equality League of Providence appear with Ingeborg as the league’s president and Maria its secretary. During the warm summer months, it was proposed to hold meetings at Oakland Beach in Warwick, but the regular meetings were held at the Kindberg/Kindstedt residence at 557 Westminster Street in Providence. The meetings appear to have been held weekly.

Meetings often had a speaker. On one occasion Ingeborg gave a talk titled “The Matrimonial System,” in which “she likened the matrimonial system to a fish net with the fish on the outside anxious to get in and the fish on the inside anxious to get out.”[2] During the meeting of March 25, 1915, the subject of the Dorr Rebellion having a possible bearing on what might be the ultimate methods resorted to by women to achieve the vote was introduced. It was decided to make the following week’s topic of discussion, “Can the Women of Rhode Island in the Fight for the Vote Copy with Advantage the Method of the Dorr Rebellion.”[3]

A Swedish language newspaper in September 1915 with reference to Ingeborg noted

She has for many years taken a lively interest in various reform projects in both social and religious areas, but at the moment she dedicates most of her attention to the women’s cause, since she believes that only through women’s participation in politics will she be able to make her voice heard in the legislative assemblies and point out the injustices and obtain those rectifications which can only be achieved by way of legislation and the implementation of which is necessary if we are to have a brighter future.[4]

When it was announced that the Congressional Union would hold a Women Voters Convention from September 14-16 at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco,[5] both Maria and Ingeborg were committed to attend.[6] Maria sold her car and they purchased steamship tickets. In late summer they set off on a journey taking them through the recently opened Panama Canal and then on their way up the coast of California.[7] Little did they know at the time but what would soon unfold would catapult them into the center of one of the most iconic events of the women’s suffrage movement and cause their names and their photos to appear on the front page of many newspapers across the country.[8]

The Congressional Union, under the leadership of Alice Paul, had been for some time collecting names on a petition to present to the U.S. Congress and President Wilson. The petition had approximately 500,000 names and the intent was to take the petition from San Francisco to Washington D.C. in time for the opening of congress on December 6, 1915. Alva Belmont who was on the National Executive Committee of the CU and a Newport summer resident may have known of Maria and Ingeborg due to their suffrage efforts back in Rhode Island. Somehow Paul learned that Maria and Ingeborg had planned to purchase an automobile and drive back to Rhode Island. Paul, always one to grasp the opportunity for publicity, thought if women envoys could drive the petition to Washington it would get good press coverage for the cause as well as provide the opportunity to collect more signatures on the petition, establish new branches for the Congressional Union, raise money for the cause, and sell subscriptions to the CU’s newspaper, The Suffragist. Maria was willing to buy a new car (an Overland Six) and do the driving, and Ingeborg was more than capable of performing the duties of mechanic, repairing the engine as needed, and fixing flat tires.

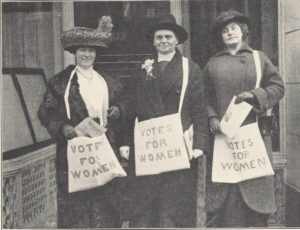

From left to right on Sara Bard Field’s auto tour: Ingeborg Kindstedt, Maria Kindberg, and Sara Bard Field, October 1915

Paul decided to add two Western women envoys to join the journey and be the face of the CU, giving talks and meeting with the press as they pulled into towns along the way. Paul asked Sara Bard Field, a poet and activist, and Frances Joliffe, a wealthy socialite, to represent the Congressional Union. But Joliffe dropped out at Sacramento due to illness.[9] Also assisting would be Mabel Vernon who would travel by train in advance of the envoys to make arrangements. Her primary task was publicity—to ensure upon their arrival a crowd would be on hand to greet the travelers and there would be press coverage.

The cross-country, 3,000-mile, adventure set out from San Francisco on September 15. The trip took ten weeks, cut across eighteen states and the District of Columbia, and encountered all sorts of mechanical and navigational problems.[10] It must be remembered that in 1915 there were no major highways conveniently populated with gas stations and motels. Often, the day’s drive was fraught with great difficulty and personal hardship. The driver and passengers faced extreme heat in the deserts of Nevada. They confronted muddy or washed out roads that were barely more than horse trails. Streams had to be forded. In the Mid-West, snowstorms had to be dealt with. Unfortunately, the Overland Six was a convertible, so the drive eastward had to be uncomfortable as the envoys made their way into winter weather.

Bad weather and bad roads were not the only troubles encountered. The relationship between Sara and Ingeborg became strained. Sara recognized that Maria and Ingeborg were ardent suffragists, but she also saw them as volunteers and not as official envoys. Most likely, all the CU leadership felt the same. The Swedish women began to get jealous that Sara was getting most of the attention. In an interview conducted many years later, Sara stated:

[T]hey were both stout and very Nordic and stolid, but the one that drove the car [Miss Kindberg] was gentle and evidently very much afraid of her companion or of not doing as her companion wished her to do, and I think that one was Miss Kindstedt ….. [S]he was very hostile to me, and one day it came out. Just where we were when it happened, I don’t know but it must have been fairly soon in the journey or perhaps in the Midwest. She suddenly turned on me and said that I was grabbing all the limelight, that while she and her companion sat on the platform every time, I always described them as driving the car at a time when women seldom would have undertaken such a journey and of being able to take care of the car, as if they were just, she said, menials. “You make all the speeches.”

I tried to explain it to her, without emphasizing it too much, that they spoke pretty broken English and hadn’t been prepared to know as much about the West as I did, and [that] all the power that we were trying to transfer to the rest of the country came from there, and that it was inevitable that I had to make the speeches, that they had lived in Boston all the time they had been in America and didn’t know much about the country as a whole and its general feeling in regard to such movements as we were undertaking. But it didn’t mollify her at all, and finally she said to me, “I’m going to kill you before we get to the end of this journey.” She said it with a fierceness and with a look in her eye that it was a little terrifying; otherwise I might have taken it as just a passive threat, as people say, “Well, I could kill you,” you know, and not mean it at all. But when I later learned that she had come out of an insane asylum—or we shouldn’t call it that; she’d been in a home for mental patients for a long time and had only been recently released, I realized I had been running a pretty serious risk.[11]

While no evidence for Sara’s claim of Ingeborg’s mental instability can be substantiated, her claim is not entirely out of the realm of plausibility.

While history books often credit Sara Bard Field for the success of the CU’s cross-country publicity trip, its success was due more to Maria and Ingeborg than anyone else. It was their money, their automobile and their skills that allowed the petition to arrive safely and in time for the opening of Congress. Certainly, it had to be galling for these two women immigrants to take a back seat to Sara Bard Field at every stop along the way. But the image the CU’s leadership wanted to project was a young, fashionable and articulate one—neither Maria nor Ingeborg had any of these characteristics. At the time of the trip Maria was fifty-five years old and Ingeborg was fifty. By comparison, Sara was just thirty-three. In looking at the women in figure 3 it is evident that Sara was dressed more fashionably when compared to Maria’s and Ingeborg’s matronly attire. And it cannot be denied that the two Swedish women, as recent immigrants, would have accents (although Ingeborg was known to lecture on women’s suffrage in Rhode Island). However, it is understandable that Maria and Ingeborg would feel unappreciated, often being treated as hired help, rather than as equals with Sara on their mutual quest.

In Chicago, a Hearst and Pathé newsreel of Sara jacking up the automobile and changing a flat tire was made. It was good for show but not accurate and was further cause for tension among the women.

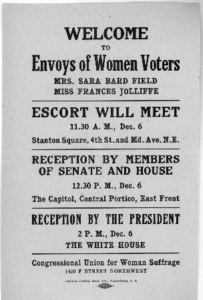

The New York Times edition of November 9, 1915, under the caption “New York To Greet Suffragist Envoys,” mentioned Sara Bard Field but also Frances Joliffe. Joliffe did not even make the grueling cross-country trip, but did join the travelers on the East Coast. The article did not mention either Maria or Ingeborg at all. A handbill to announce the welcome of the women suffrage envoys on December 6, 1915 in Washington, D.C. (see figure 4) mention both Field and Joliffe, Kindberg and Kindstedt are not referenced.

Left to right, Maria Kindberg, Sara Bard Field, Mabel Vernon and Ingeborg Kinstedt in Washington, D.C. at the end of their journey

Following the events in Washington, D.C. Maria and Ingeborg headed home to Providence. Along the way they encountered a severe snowstorm. In a letter to Alice Paul, Ingeborg mentioned she broke her watch shoveling out of a snow drift. Presumably this was the same watch that Alva Vanderbilt Belmont presented each to Maria and Ingeborg for their service in the cross-country trip. In the same letter Ingeborg noted “All the leagues of R.I. are stirred up at present. Several of them have called upon me but I answer them that the Woman’s Political Equality League will [indecipherable] to a branch of the Congressional Union if they still exist at all. I would like your information as to the matter at once.”[12] In another letter to Paul written on December 24, [1915] from Agnes Jenks of the rival Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association stated: “ I saw by this morning’s paper that Miss Kindberg and Miss Kindstedt are thinking of turning their moribund association which is called The Political Union, into a branch of the Cong. Union. It seemed to me only fair to tell you that this association is not a living thing, it is a name and headed by the two women, it cannot be an association in fact.” Jenks ended her letter with a warning: “… if either of them two women are given a free hand, it will close your chances of good work here. This is just friendly advice and covers my present knowledge of the situation here.”[13] Regardless of the warning just two month later on March 6, 1916 Maria and Ingeborg along with three other women filed with the Rhode island Secretary of State incorporation papers under the name Congressional Union of Providence, Rhode Island. They would continue to work for woman suffrage until ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920. (Rhode Island ratified the amendment on January 6, 1920.)

Handbill announcing Welcome to Envoys of Women Voters December 6, 1915 (image courtesy of Library of Congress)

For Maria and Ingeborg, the afterglow of their suffrage efforts was short lived. On March 25, 1921, both women applied for passports; their stated purpose was to enter Sweden in order to visit relatives. Their scheduled departure was to be on April 21 on the SS Stockholm, but unfortunately they never went. By June 7 Maria was dead by her own hand. Ingeborg never appeared in any activist role thereafter. Her name continued to appear in the Providence Directory with an occupation of housekeeper. In 1933 she returned permanently to Sweden and died there on August 5, 1950. Underappreciated in their time and often overlooked today, both of these remarkable women are worthy of inclusion in any listing of suffragists who made a difference in the woman’s suffrage movement in the United States.

[Banner image: From left to right on Sara Bard Field’s auto tour: Ingeborg Kindstedt, Maria Kindberg, and Sara Bard Field, October 1915]

[Author’s Acknowledgement: I wish to thank Anne Gass of Gray, Maine, who provided much information for this essay and is conceivably the leading authority on Maria Kindberg and Ingeborg Kindstedt.]

Notes

[1] Ingeborg Kindstedt’s naturalization card filed with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service shows her arriving in the United States in October 1890, while a passenger list found on Ancestry.com shows her arriving in New York on September 27, 1890 on the RMS City of Chester. [2] Providence Journal, December 25, 1914. [3] Providence Journal, March 26, 1915. [4] Vestkusten, September 23, 1915. [5] The Panama Pacific Exposition ran from February 20 to December 4, 1920. The exhibition located in the Marina District of San Francisco was represented by twenty-four countries. [6] Maria and Ingeborg were staunch supporters of the Congressional Union. As noted by Sara Algeo in her book The Story of a Sub-Pioneer “From its earliest inception the flag of the Congressional Union, purple, white and gold, with a large sign Congressional Union, flew from their home on Westminster Street.” [7] The Panama Canal officially opened on August 15, 1914. [8] This cross-country trip, a publicity stunt sponsored by the Congressional Union, was commemorated on a U.S. postage stamp in 1970 in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. [9] While Joliffe claimed illness, it has been said she came to realize the hardships to be endured on the trip and decided to drop out opting instead to travel east by train to meet up with the envoys once they reached the East Coast. [10] The first United States cross-country automobile trip occurred just a dozen years earlier when Horatio Nelson Jackson of Vermont and his driver/mechanic Sewall K. Croker left San Francisco on May 23, 1903 and arrived in New York City sixty-three days later. Many of the hardships encountered by Jackson were also encountered by the ladies of the Congressional Union sponsored trip. [11] See the Berkeley Library, University of California online Suffrage History Project’s interview of Sara Bard Field conducted by Amelia Fry: http://texts.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt1p3001n1&doc.view=entire_text. [12] National Woman’s Party papers. Part 2. Series1, Reel 2, LOC. [13] Ibid., Reel 22.

Bibliography

Algeo, Sara M. The Story of a Sub-Pioneer ( Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham Company, 1925).

Clarsen, Georgine Eat My Dust: Early Women Motorists (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

Clift, Eleanor Founding Sisters and the Nineteenth Amendment (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

Conkling, Winifred Votes for Women! American Suffragists and the Battle for the Ballot (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2017).

Gurko, Miriam The Ladies of Seneca Falls: The Birth of the Woman’s Rights Movement New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1974).

Kroeger, Brooke The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote, Excelsior Edition (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2017).

Neuman, Johanna Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites Who Fought for Women’s Right to Vote (New York, NY: Washington Mews Books, New York University Press, 2017).

Ward, Geoffrey C. and Burns, Ken Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999).

Zboray, Ronald J. and Zboray, Mary Saracino Voices Without Votes: Women and Politics in Antebellum New England (Lebanon, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2010).