The Washington Post, in its January 16, 2022 edition, published a first-of-its-kind database revealing that more than 1,700 United States Senators and Congressmen once held enslaved people at some point in their lives. The enslavers, who served from 1789 (the first federal Congress) to well after the Civil War, represented 37 states, including not just the South, but every state in New England and much of the Midwest.

The fact that there were so many slave holders in Congress must have influenced their voting on matters involving slavery and the African slave trade, which matters arose frequently in the period from 1789 to the Civil War. The Washington Post database indicates that for the first eighteen years of the U.S. Congress’s existence, from 1789 to 1807, “more than half the men elected to Congress each session were slaveholders.”

Some were owners of enormous plantations, such as Senator Edward Lloyd V of Maryland, who enslaved 468 people in 1832 on the same estate in the Eastern Shore where the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass was enslaved as a child. Others, particularly some of those in the North, owned a single enslaved person at some point in their lifetimes, and not necessarily when they served in Congress.

In New England, each of the states that had formerly been colonies of Great Britain—Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Hampshire—had enslaved people in their midst in colonial times. Throughout New England in colonial times, the black population consisted of about two percent of the total population.

In Rhode Island, on the eve of the American Revolution, the percentage of blacks in the population (most of whom were enslaved) was about six percent. There are two primary reasons for this higher percentage. First, Rhode Island (particularly Newport, later joined by Bristol) dominated the African slave trade among slave trading merchants and captains in North America. Second, in southern Rhode Island, in what is now Washington County, large dairy and horse farms arose that were largely worked on by enslaved labor. The largest slaveholders in Rhode Island typically held in bondage from 5 to 20 people.

The American Revolution, with its reliance on the liberty of the individual and equality of opportunity, was a watershed moment in the advancement of human freedom in world history. It also was an important event in the antislavery movement in world history. Before the American Revolution, there was little antislavery activity in the world; by the end of the American Revolution, American participation in the African slave trade had a fixed ending date, and the states in the North had either ended slavery or were on the path to doing so.

Abolition in New England was not instantaneous and differed state-by-state. When Vermont was formed in 1777, it was the first state to ban slavery in its constitution. Massachusetts banned slavery in 1781, by judicial court decisions interpreting the first article in the state’s new constitution—“All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights. . . .”.

Rhode Island and Connecticut took a different route in 1784—gradual emancipation. Only children born from enslaved mothers after the legislation was passed could be free, and only after they reached the age of maturity.

In actuality, the institution of slavery in Rhode Island weakened at a more accelerated rate than the gradual emancipation law envisioned. In 1774, there were likely more than 3,000 enslaved persons in Rhode Island, but by 1790 there were 948 and by 1800 just 380. Most enslaved persons in Rhode Island had been freed, either by service in the American army, manumission by their owners, through negotiations between white owners and the enslaved adults, or by the enslaved persons freeing themselves by running away. Many of those who remained enslaved were elderly, who may not have been able to support themselves if freed, and children born after 1784 who would eventually become free. Some slaveholders, however, stubbornly held on to their enslaved people, or inherited them.

Rhode Island had eight Senators and Congressmen who at one point in their lives held one or more enslaved people. This compares to Vermont (1), Maine (1), Massachusetts (2), New Hampshire (3), and Connecticut (14). The fact that Rhode Island and Connecticut adopted gradual emancipation approaches explains their higher numbers. The sons of slaveholders sometimes inherited the enslaved people held by their parents.

The eight Rhode Island Senators and Congressmen hailed from the following towns: Newport (two), Bristol (two), South Kingstown (then including Narragansett) (two), and Providence (two) (one listed Senator lived in what was then Cranston but is now part of Providence).

Five of the Senators and Representatives were from the Federalist Party (the party of Alexander Hamilton and John Adams), which tended to be the party of well-to-do merchants and supporters of Rhode Island’s admission into the Union. The remaining three were Democratic Republicans, the party of Thomas Jefferson.

Set forth below are the eight Rhode Islanders who served in Congress and at one point in their lives held one or more enslaved people, in alphabetical order.

William Bradford (1729-1808)

- Senator (1793-1797)

- Party: Federalist

- Short Biography: William Bradford was born in Plympton, Plymouth County, Mass., November 4, 1729; studied medicine in Hingham, Mass., and afterwards practiced in Warren, R.I.; moved to Bristol, R.I.; abandoned the profession of medicine and studied law; admitted to the Rhode Island bar in 1767 and commenced practice in Bristol; member, State house of representatives for several terms between 1761 and 1803, serving as speaker on several occasions; member of the Rhode Island Committee of Correspondence in 1773; deputy governor of Rhode Island 1775-1778; elected as a Delegate to the Continental Congress in 1776 but did not attend; elected to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1793, until October 1797, when he resigned; served as President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate during the Fifth Congress; retired to his home in Bristol, R.I., and died there on July 6, 1808; interment in East Burial Ground.

Slaveholding History: Bradford had two black persons residing in his Bristol household, as reported in Rhode Island’s 1774 census. Both persons were likely enslaved. In the 1790 census, Bradford is reported as having two enslaved persons in his household. Bradford was willing to oppose antislavery proposals. In 1774, the Rhode Island General Assembly considered measures to prohibit the importation of enslaved people and to ban slavery in the colony. The first measure passed, but the slavery ban did not, with Bradford speaking firmly against it.

John Brown (1736-1803)

- Representative (1799-1801)

- Party: Federalist

- Short Bio: John Brown was born in Providence, R.I., January 27, 1736; engaged in mercantile pursuits; one of the party which destroyed the British sloop of war Gaspee in Narragansett Bay June 9, 1772; sent in irons to Boston for trial, but released through the efforts of his brother Moses; laid the cornerstone of the first building of the College of Rhode Island (now Brown University) May 14, 1770; trustee of Brown University, Providence, R.I., 1774-1803; treasurer 1775-1796; member of the State house of representatives 1782-1784; chosen as a Delegate to the Continental Congress in 1784 and 1785, but did not serve; elected as a Federalist to the Sixth Congress (March 4, 1799-March 3, 1801); resumed his former business pursuits; died in Providence, R.I., September 20, 1803; interment in the North Burial Ground.

Slaveholding History: In the 1774 and 1782 censuses for Rhode Island, Brown had two black persons living in his household. In 1778, in a tax document he submitted to the town of Providence that I found, Brown reported that he had two enslaved people and leased several others on a part-time basis. Accordingly, those black people listed as in his household in 1774 and 1782 were also likely enslaved. In the federal censuses of 1790 and 1800, Brown is not reported as having any enslaved people in his household. From the census records, at least, Brown did not hold enslaved people during the period he served in Congress.

Brown also participated as in investor in the African slave trade. While slave trading was never central to his extensive mercantile business, he invested in African slave trade voyages from Providence in 1763-64, 1769, 1785, 1786, and 1795. The 1763-64 voyage was one of the most deadly of all the slave trading voyages undertaken by North American merchants, with 109 African captives dying in the Middle Passage.

In 1778, Brown was the main investor and mastermind behind the voyage of the privateer Marlborough, which sailed to Africa and captured British slave ships with African captives on board, with the goal of selling them to French or Southern U.S. plantation owners (as set forth in my new book, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade).

In 1797, as a result of sponsoring an illegal 1795 slave voyage to Cuba, Brown was the first Rhode Islander, and probably the first American, to be tried under the Slave Trade Act of 1794. Though he was acquitted of criminal charges, his ship Hope was forfeited and placed at auction. In 1799, Brown and others personally paid a call upon Samuel Bosworth, the surveyor of the port of Bristol, warning him not to take part in an auction of another slave ship (not owned by Brown) the next morning. Bosworth ignored the threat, and while walking to the auction the next day, the federal official was kidnapped and deposited two miles down Narragansett Bay. This attack intimidated federal and state officials and effectively halted enforcement of the Slave Trade Act. He once exclaimed, “in my opinion there is no more crime in bringing off a cargo of slaves than in bringing off a cargo of jackasses.”

In Congress, Brown actively resisted attempts to restrict participation of United States citizens in the African slave trade.

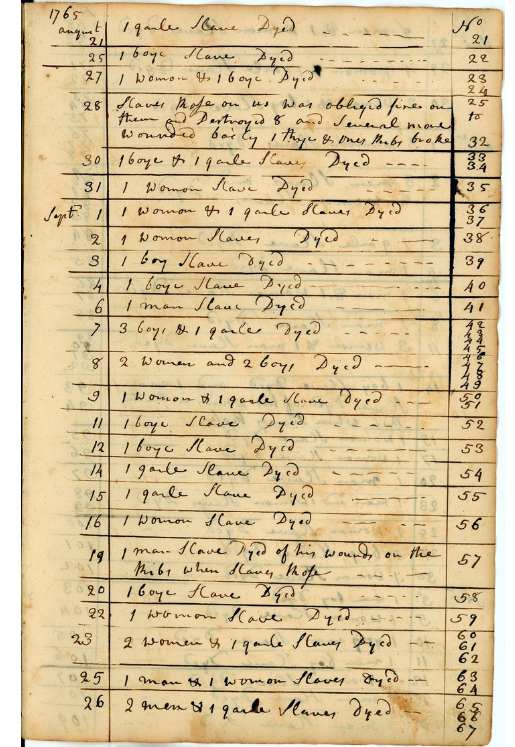

Page from Esek Hopkin’s Account Book for the voyage of the slave ship Sally, 1764, listing captives nos. 21 through 67. Note the number of captives who “dyed” on the voyage (John Carter Brown Collections, from the Brown University Study of Slavery and Brown University)

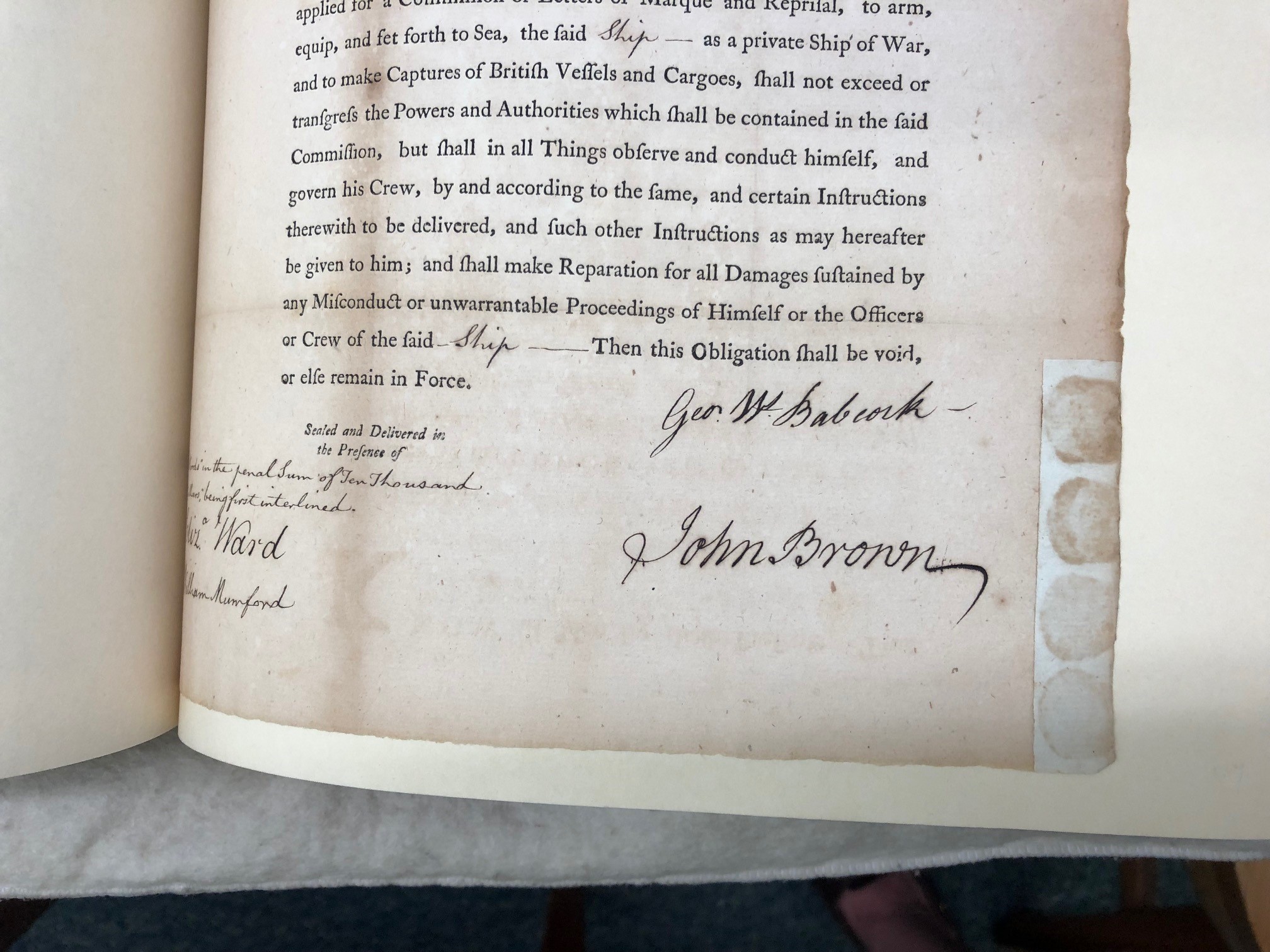

John Brown’s signature on the commission for the privateer Marlborough (Rhode Island State Archives)

- Christopher Grant Champlin (1768-1840)

- Representative (1797–1799, 1799–1801, 1809–1811, and 1811–1813), Senator (1809-1811)

- Party: Federalist

- Short Bio: Christopher Grant Champlin was born in Newport, R.I., April 12, 1768; completed preparatory studies; was graduated from Harvard College in 1786 and continued his studies at the College of St. Omer in France; elected as a Federalist to the Fifth and Sixth Congresses (March 4, 1797-March 3, 1801); engaged in mercantile pursuits; elected as a Federalist to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Francis Malbone and served from June 26, 1809, to October 2, 1811, when he resigned; president of the Rhode Island Bank until a short time before his death in Newport, March 18, 1840; interment in Common Burial Ground.

Slaveholding History: Champlin’s father was Christopher Champlin (1731-1805), who moved with his brothers from Charlestown to Newport to begin a career as a merchant. The father and his brother George, prior to the American Revolution, were substantial investors in several African slave trading voyages. Christopher Grant Champlin, after going on a European tour meant to “refine” him, returned, settled in New York, and lost a fortune in stock speculation. He returned to Newport, marrying Martha Redwood Ellery in 1793. He then joined his father in the mercantile trade, before running for Congress in 1796. The Champlins continued in the slave trade business until at least 1799.

Christopher Grant Champlin’s father, in the Rhode Island 1774 census, is listed as having two black people in his household and fourteen on his farm across Narragansett Bay in Charlestown. All were likely enslaved. In the 1790 census, the father is listed as having one enslaved person in Newport, and another at his farm in Charlestown.

The 1800 census is the only census indicating that Christopher Grant Champlin held an enslaved person—he is listed as having one.

While Christopher Grant Champlin served with John Brown in the 1799-1801 term in the House of Representatives, Champlin reportedly refrained from joining Brown in resisting proposed restrictions on Americans participating in the African slave trade.

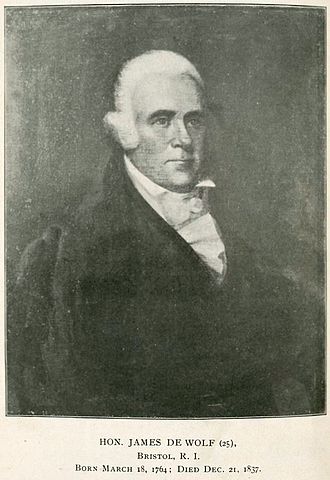

James DeWolf (1764-1837)

- Senator (1821-1825)

- Party: Democratic Republican

- Short Bio: James DeWolfe (spelled De Wolf on the Congressional website) was born in Bristol, R.I., March 18, 1764; during the Revolutionary War shipped as a sailor on a private armed vessel; participated in several naval encounters and was twice captured by the enemy; before he was twenty years old became captain of a ship; engaged in extensive commercial ventures, principally trading in slaves, with Cuba and other West Indian islands; member, State house of representatives 1797-1801, 1803-1812; fitted out a privateer in the War of 1812; one of the pioneers in cotton manufacturing; built the Arkwright Mills in Coventry, R.I., in 1812; member, State house of representatives 1817-1821, and served as speaker 1819-1821; elected as a Democratic Republican (later Crawford Republican) to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1821, to October 31, 1825, when he resigned; member, State house of representatives 1829-1837; died in New York City December 21, 1837; interment in the DeWolf private cemetery, Woodlawn Avenue, Bristol, R.I.

Slave Holding: James DeWolf, of Bristol, was probably Rhode Island’s greatest slave trader. Most of it was illegal, banned under both state and federal law. In 1791, a federal grand jury in Rhode Island charged DeWolf with a federal crime for the murder of an African woman on a slave trading voyage. DeWolf decided to throw the woman overboard, after she contracted smallpox. He went overseas for about four years, thus avoiding service of the warrant.

In only one federal census is De Wolf reported as having enslaved people in his household—1810. In that year, DeWolf is listed as having 3 enslaved people in his household. In 1820, he was reported as having 20 persons living at his large home in Bristol, 17 whites and 3 free nonwhite persons. It could be that the three enslaved people reported in 1810 were children born of enslaved mothers who had attained the age of maturity and were freed by 1820. In the 1790 federal census, none of the DeWolfes in Bristol was listed as having an enslaved person at his house. They may not have been telling the truth.

DeWolfe also owned three large sugar and coffee plantations in Cuba, reportedly cultivated by hundreds of enslaved people. He married the daughter of William Bradford (#1 above).

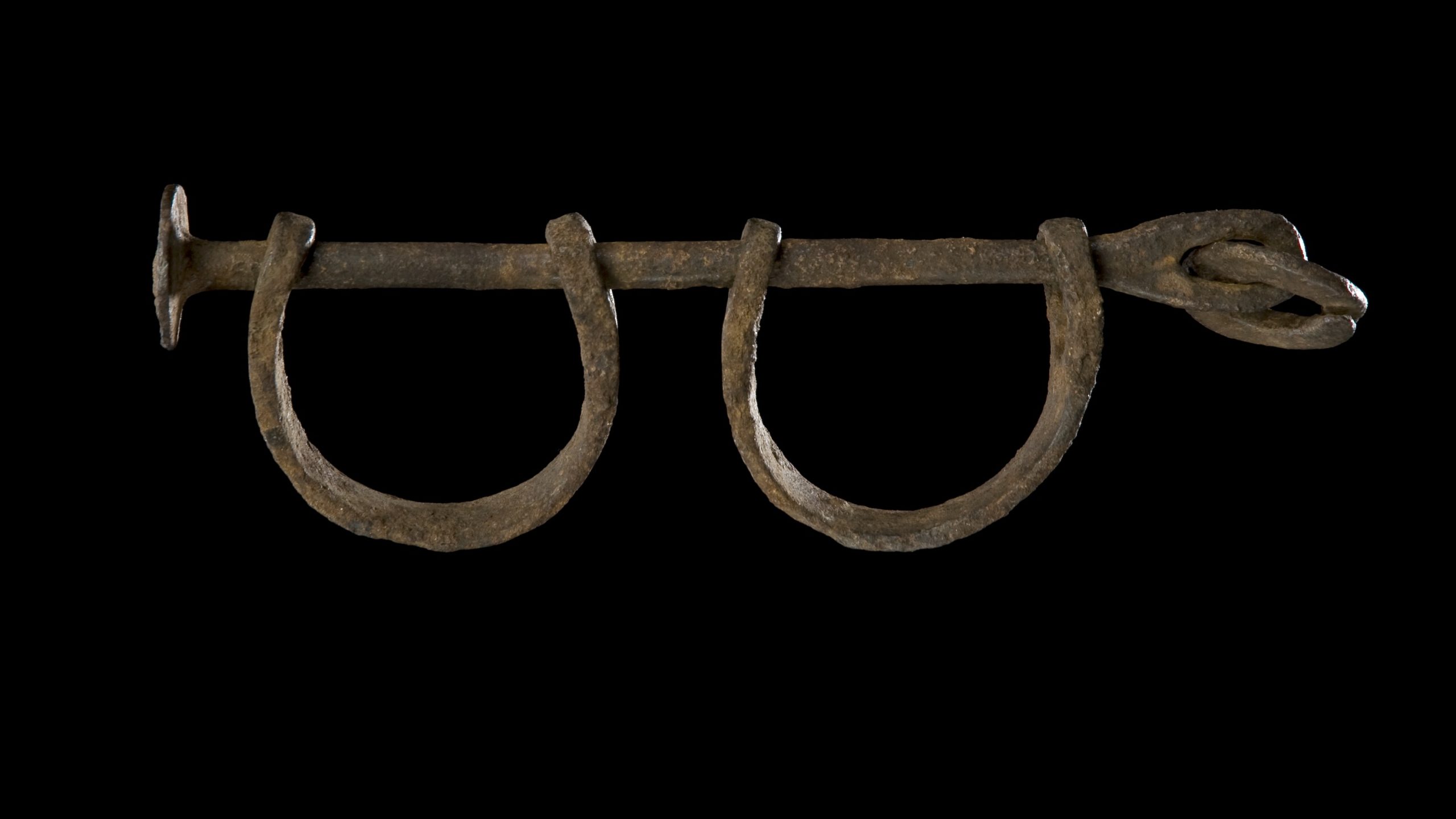

Leg restraints used to transport enslaved people (Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Nehemiah Knight (1746-1808)

- Representative (1803–1805, 1805–1807, and 1807–1809)

- Party: Democratic Republican

- Short Bio: Nehemiah Knight was born in Knightsville, Cranston (now a part of Providence), R.I., March 23, 1746; attended the common schools; engaged in agricultural pursuits; town clerk 1773-1800; elected to the general assembly of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in 1783 and again in 1787; sheriff of Providence County in 1787; elected as a Republican to the Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Congresses and served from March 4, 1803, until his death in Cranston, R.I., June 13, 1808; interment in a small cemetery on Cranston Street and Phoenix Avenue in Providence, R.I. His son Nehemiah R. Knight (born in 1780) was Governor and U.S. Senator from Rhode Island.

Slave Holding: The area where Knight lived, Knightsville in what is now Providence, was not an area that ever had many enslaved people. Knight was not listed as having any black people living in his home in the censuses of 1774 or 1782. No slave was listed living at his house in the 1800 federal census. But in the 1790 census, Knight is reported to have had two enslaved people residing at his home. He probably purchased them after the state’s 1784 gradual emancipation legislation had passed.

Francis Malbone (1759-1809)

- Representative, (1793–1795), 4th (1795–1797), 11th (1809–1811), Senator: 1793-95, 1795-1797

- Party: Federalist

- Short Bio: Francis Malbone was born in Newport, R.I., March 20, 1759; received a limited schooling; engaged as a merchant in Newport; colonel of the Newport Artillery 1792-1809; elected to the Third and Fourth Congresses (March 4, 1793-March 3, 1797); was not a candidate for renomination; resumed his former pursuits; member, State house of representatives 1807-1808; elected as a Federalist to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1809, until his death on the steps of the Capitol in Washington, D.C., June 4, 1809; interment in the Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C.

Slave Holding: Malbone’s father, Francis Malbone, Sr., was reportedly a native of Princess Anne County in Virginia, and came to Rhode Island about 1758. In the 1774 Rhode Island census, Francis Malbone, Sr. is reported as having 10 black people at his residence, all of whom were likely enslaved. In the 1782 census, Francis Malbone, Sr. is reported to have had 5 black persons residing at his Newport house, and Francis Malbone, Jr. was listed as having 2 black persons at his Newport house. It is likely most or all were enslaved. In the 1790 census, Francis Malbone, Jr. was reported as having 3 enslaved people in his home. By contrast, in 1800, Malbone still had three nonwhite people living at his Newport home, but they were then free.

Elisha Reynolds Potter, Sr. (1764-1835)

- Representative: 1795–1797, 1797–1799, 1809–1811, 1811–1813, and 1813–1815

- Party: Federalist

- Short Bio: Elisha Reynolds Potter (father of Elisha Reynolds Potter, Jr., also later a Representative) was born in Little Rest (now Kingston), R.I., November 5, 1764; learned the blacksmith’s trade and also engaged in agricultural pursuits; served as a private in the Revolutionary War; attended Plainfield Academy; studied law; was admitted to the bar about 1789 and commenced practice in South Kingstown Township, R.I.; member of the State house of representatives, 1793-1796 and served as speaker in 1795 and 1796; elected as a Federalist to the Fourth Congress to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Benjamin Bourn and served during the Fifth Congress (November 15, 1796-1797), until his resignation; again a member of the State house of representatives, 1798-1808 and speaker in 1802 and 1806-1808; elected to the Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Congresses (March 4, 1809-March 3, 1815); from 1816 to 1835 was a member of the State house of representatives except the year 1818, when he was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Rhode Island; died in South Kingstown, R.I., September 26, 1835; interment in the family burial ground, Kingston, R.I.

Slaveholding: Potter started out as a blacksmith but through inheritance and business acumen he became a large landowner, based in Little Rest (what is now Kingston in South Kingstown). (I grew up in his house, built in 1809). Potter’s father and grandfathers were slaveowners. Potter is known to have hired temporary free black laborers in the 1800s. In the federal censuses, he is not reported as having an enslaved person residing at his house, with one exception. In 1800, one enslaved person was listed in his household. The enslaved person was John Potter. How Elisha Potter acquired him is not known; he probably inherited him. It appears John Potter was birthed by an enslaved mother after the gradual emancipation law of 1784. In August 1810, Elisha Potter brought John Potter before the South Kingstown Town Council, which agreed to issue a certificate to John Potter demonstrating his freedom. Presumably, John Potter had just turned age 21 and had therefore qualified for emancipation under the 1784 statute. If so, John Potter had not been enslaved for life.

Samuel John Potter (1753-1804)

- Senator (1803-1804)

- Party: Democratic Republican

- Short Bio: Samuel John Potter was born in South Kingstown, R.I., June 29, 1753; served as an officer of the South Kingstown militia during the Revolutionary War; completed preparatory studies; studied law; admitted to the bar and practiced; an antifederalist opposing Rhode Island’s entry into the Union; deputy governor of Rhode Island, 1790-1803; presidential elector in 1792 and 1796; elected as a Democratic Republican to the United States Senate and served from March 4, 1803, until his death in Washington, D.C., October 14, 1804; interment is not known—it was likely in Washington County, R.I.

Slaveholding: He lived at Point Judith, on a farm given to him by his father, John Potter, a substantial slaveholder. Potter is listed as having a single enslaved person in his household in just one Rhode Island census—for 1800.

* * *

Two other Rhode Island U.S. Senators are worth mentioning. In the Washington Post article, William Hunter of Newport was inaccurately identified as a Rhode Island Senator who once held at least one enslaved person. The mistake was brought to the attention of a Washington Post reporter by Timothy Phelps, who is a historian of the Rhode Island slave trade and a descendant of the Hunters. The reporter admitted that she had misread a page from the 1820 census and agreed to remove William Hunter from the list, which has been done.

Another U.S. Senator worth mentioning is Joseph Stanton, Jr. of Charlestown. He was a colonel in the Rhode Island militia during the American Revolutionary War and later became general of the state militia. He was one of the two first U.S. Senators from Rhode Island, serving from 1790 to 1793. He was a leader of the antifederalists, who opposed the state’s admission to the Union. When he later served in the U.S. Congress from 1801-1807, he was a member of the Democratic Republican Party. A February 26, 2021 article in the Providence Journal, entitled “Hidden in Plain Sight – Prominent Rhode Island Families has Slaves in 1700s Charlestown,” begins at a monument on Route 1 in Charlestown honoring Joseph Stanton, Jr. The monument is near the Wilcox Tavern, the former family home of the Stantons. The article hints that Senator Stanton was a slaveholder. Pamela Lyons of the Charlestown Historical Society was quoted in the article as replying, “General Joseph Stanton actually helped establish the Providence Abolition Society” in 1790 with antislavery leader Moses Brown.

Joseph Stanton, Sr., the father of Joseph Stanton, Jr., likely was a slaveholder. In the 1774 census, he is reported as having four black people residing in his household. At this time, most of the black people in Rhode Island were enslaved. However, the black people could have been servants.

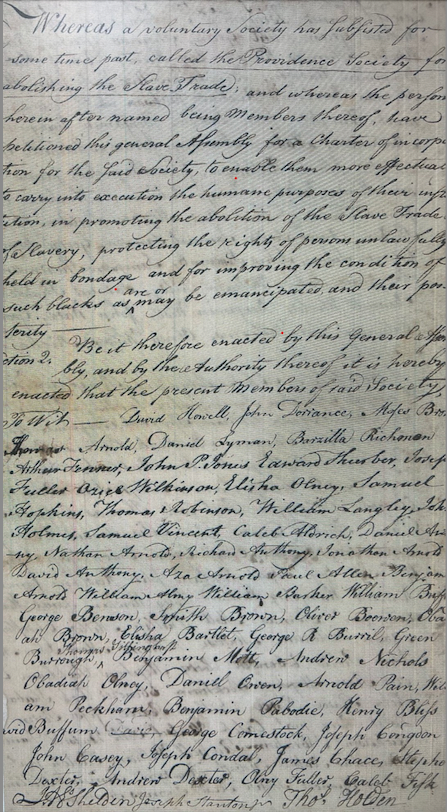

The Rhode Island census listings for Joseph Stanton, Jr. reveal the following black people residing at his Charlestown home: 1774, 0; 1782, 1; 1790, 1; and 1800, 2. The 1782 census did not indicate whether a black person was enslaved or not. By that time, many formerly enslaved people had become free. The black people living at Stanton’s home in 1790 and 1800 were listed as free persons. The fact that Stanton had one and then two free black people working at his home in 1790 and 1800 is some proof that the black person living at his home in 1782 was also not enslaved. Moreover, Joseph Stanton, Jr. was listed as one of the original members of the Providence Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and Slavery, when it received its charter from the state in June 1790. While not certain, based on the above evidence, there is no strong evidence I am aware of indicating that Joseph Stanton, Jr., ever held an enslaved person.

[Banner Image: John Brown’s signature on the commission for the Rhode Island privateer Marlborough, Dec. 13, 1777 (Rhode Island State Archives).]

Page from a petition to the General Assembly to incorporate the Providence Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and Slavery, June 1790, showing the name of Joseph Stanton, Jr. (at the very bottom) as an original incorporator (Rhode Island State Archives)

Sources

The information for each man in in the indented subparagraphs above is primarily from the online Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, at www.bioguide.congress.gov. The information in the subheading “slaveholding” I gleaned from two types of sources. The first is censuses of Rhode Island—the U.S. federal censuses from 1790 to 1840 (accessed online at www.ancestry.com), as well as published Rhode Island censuses for 1774 and 1782 (see below). The other source is information I have learned from my prior research, particularly on John Brown, Christopher G. Champlin, and Elisha Reynolds Potter, Sr. I did not do any special research to find out more information on the slaveholdings of the men above. More research could divulge more complete information.

John R. Bartlett, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Taken by the Order of the General Assembly, in the Year 1774 (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony, 1858).

Jay Holbrook, Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979).

For Christopher G. Champlin, see a short biography of him on the Rhode Island Historical Society website at https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/Mss020.htm and his Wikipedia entry at Christopher G. Champlin – Wikipedia

For James DeWolfe and Christopher Champlin, see Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700–1807 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981).

For John Brown, see Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), and Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2022).

For Elisha Reynolds Potter, Sr., see Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society), 2004.

For Joseph Stanton, Jr. being an original member of the Providence Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and Slavery, Petitions with the General Assembly, Act Incorporating the Society for the Abolition of Slavery, June 1790, Rhode Island State Archives.