A major trend that produced the new (but briefly tenuous) Democratic ascendancy was the movement of Franco-American voters into the Democratic Party, especially after Governor Aram Pothier’s death in office on February 4, 1928. Many factors influenced this important trend: (1) the textile industry experienced a drastic decline from 1923 onward, creating high unemployment in the Franco-American community and dissolving the economic bond between the French and their Yankee Republican employers; (2) Irish Democrats continued to woo the Franco-Americans by sponsoring working-class legislation and advancing Franco-Americans like Alberic Archambault to prominent positions in the Democratic party; (3) the shift in national Democratic leadership from William Jennings Bryan’s agrarian wing to an urban ethnic base made the party more attractive to blue-collar workers; (4) the presidential candidacy of Catholic Democrat Al Smith brought Catholic ethnics into the Democratic fold; (5) the failure of the Republicans to deal effectively with the Great Depression caused disillusionment with the GOP, especially among the unemployed; and (6) the social programs, labor legislation, and proethnic attitude of the federal government under the New Deal cemented the allegiance of French Canadians and other new ethnics like the Italians, Poles, and Jews to the Democratic party.

Alberic Archambault, a West Warwick colleague of Colonel Quinn, led the move of the French from the GOP to the Democratic Party. Irish party leaders nominated Archambault for governor in 1918 and 1928 and elected him state party chairman in 1920-21.

Although there is no scholarly statistical analysis of the Franco-American conversion to the Democratic fold, Stefano Luconi has studied the Italian transition in his book The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island, 1916-1948 (2004). This work concludes that the Democratic Party by providing political recognition and patronage also shaped the voting behavior of Italian Americans. Control of the city councils and city patronage via Article of Amendment XX in 1928, the candidacy of Al Smith (who ironically had a paternal grandfather from Italy), Democratic control of state patronage after the repeal of the Brayton Act and the reorganization of state government in January 1935 lured Italian Americans into the Democratic camp.

Cover page for a new book on Robert E. Quinn to be published by the Rhode Island Publications Society later this year. Patrick T. Conley’s two-part article on Quinn will appear in this book (Rhode Island Publications Society)

Luigi DePasquale was, like Archambault, the pioneer in leading his fellow ethics towards the Democratic Party. He received the nomination for Congress in 1920 and nearly won. Until that time no Italian-American from either party had been advanced for high office. In 1925 DePasquale was named state Democratic party chairman. According to Bob Quinn this choice was designed “to make hay with the Italians.”

In 1932 Louis Cappelli became the first Italian-American to win general office. He was elected secretary of state on the victorious slate headed by Green and Quinn. By the mid-1930s Christopher Del Sesto and John O. Pastore began their climb up the political ladder. The Democratic leaders also gave deference to Republican Antonio Capotosto when they reorganized the Supreme Court in January, 1935. He became one of the two Republican justices on the new high court. Making Columbus Day (October 12) a legal state holiday in 1936 was another Democratic ploy that was as much political as it was historical.

In the statewide elections of 1936, the Democrats called a moratorium on their intraparty feud long enough to secure control of every political plum except the malapportioned and traditionally Republican state Senate, in which the Republicans had regained control by the surprising margin of 27 to 15. The December, 1936 special session was called by Green and Quinn so that the outgoing General Assembly, with its lame-duck Democratic Senate, could enhance gubernatorial power in several areas, such as by conferring upon the governor the right to appoint sheriffs and clerks of the Supreme and Superior Courts. This measure came on the heels of a 1935 Democratic raid upon District Court clerks and judges, which the new Supreme Court had upheld by a 3-to-2 margin in Gorham v. Robinson, 57 R.I. 1 (1936) a decision denying the applicability in Rhode Island of the doctrine of strict separation of powers.

Although McCoy did well at this special session by securing the passage of an act that increased his control over Pawtucket’s police and fire departments, he again failed to win approval for his great obsession–municipal ownership of public utilities. Both Green and lawyer-lobbyist Cornelius C. Moore of Newport consistently blocked McCoy’s populistic crusade against Blackstone Valley Gas and Electric and other utility companies.

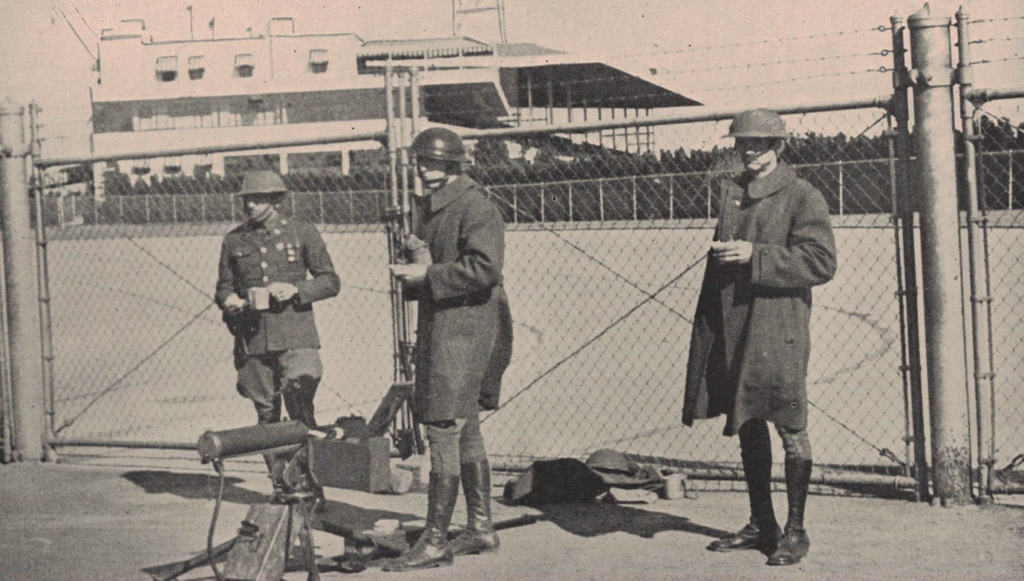

Members of the Rhode Island National Guard block the entrance to the Narragansett Race Track in the fall of 1937 (Rhode Island National Guard)]

Because of such opposition and his failure to secure greater statewide influence, McCoy moved closer politically to the flamboyant Walter O’Hara. He would side with the Pawtucket Star’s publisher and Narragansett Race Track proprietor when O’Hara battled Governor Quinn in the notorious Race Track War which was waged by this determined duo during the autumn of 1937.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The bizarre manner by which the Democrats seized power in January 1935 was equaled by the way they soon squandered it. No victorious party in Rhode Island history was as fractionalized and divided on policy issues. Few, if any, were as preoccupied with the spoils of office and their distribution, especially as rewards to the party’s new ethnic allies.

Our interviewer, Matt Smith, in his insightful 1973 essay, “The Real Mc Coy in the Bloodless Revolution of 1935,” has described this divisiveness better than anyone. According to Smith, “the power structure of the Democratic Party in 1935 consisted of four major factions . . . . to a large degree geographic in nature, but with plenty of leeway for personal friendships and alliances, they were constantly maneuvering for power.” Those factions were a Providence combine headed by Green and his law partner, ex-mayor Joseph H. Gainer; the Peter Gerry camp whose driving force, J. Howard McGrath, a Woonsocket native, became state party chairman in 1930; the Pawtuxet Valley organization headed by the Quinns and including Franco-American leader Alberic Archambault, and the Blackstone Valley combine composed of party leaders in Woonsocket, Central Falls, and especially Pawtucket. It was led by Pawtucket political boss and soon-to-be mayor, the audacious Thomas P. McCoy. It also included Pawtucket’s Albert J. Lamarre and Harry Curvin, Congressman Francis Condon of Central Falls, and the fiery Felix Toupin of Woonsocket.

These contingents were analogous to the final four in the current college football playoffs, and they fought as hard for supremacy. As Smith correctly observes, “the General Assembly session that followed the historic “revolution” must be regarded as one of the low points in the party’s history. Instead of following upon its initial reform impulse with a program for long-promised constitutional change and badly-needed social welfare legislation, newly empowered legislators matched their Republican predecessors in a wild scramble for patronage and power.”

The initial major confrontation, which was between Green and McCoy, erupted early. The governor had made McCoy state budget director and comptroller because of his proven financial acumen and because he controlled ten votes in the House. However, McCoy was passionate about municipal ownership of public utilities as a result of his long battle with the Blackstone Valley Gas and Electric Company to cut its rates for consumers. Green, influenced by such utility company lobbyists as Newport lawyer and Democratic leader Cornelius Moore, rejected this reform despite his support for it in his inaugural message. The utility issue soon grew very bitter and when combined with a fight over patronage, Green fired the insubordinate McCoy in April and replaced him with a rising Italian star–Christopher Del Sesto.

Ironically, Del Sesto in later years would be angered when the Democratic Party leadership passed him over for advancement in favor of John O. Pastore. A resentful Del Sesto then joined the GOP and won the governorship in 1958. This episode was also skillfully related by Matt Smith in his scholarly article on “The Long Count and Its Legacy.” Felix Toupin, another foe of Green, defected even sooner and became the Republican mayor of Woonsocket in 1938.

Newspaper cartoon from the Pawtucket Star, Nov. 1936, showing three key Democratic leaders who spearheaded the Bloodless Revolution of 1935: Robert E. Quinn (center), Theodore F. Green (right), and Thomas P. McCoy (left) (Russell DeSimone Collection)

Like McCoy, Lieutenant Governor Quinn also experienced frustration. His overriding goal since his entry into politics as a candidate for the House in 1922 had been a constitutional convention to reform and transform state government. This goal was also thwarted.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Equal Rights Movement of the 1880s, led by Irish American attorney Charles E. Gorman, a leading Democrat, had demanded a constitutional convention to effect sweeping reforms in Rhode Island’s basic law, especially in the area of voting rights. That effort was stymied in 1883 by a Republican-dominated state supreme court, which rendered an advisory opinion to the Senate, 14 R.I. 649 (1883), declaring that a constitutional convention could not be convened either by the people (as the Dorrites had done) or by the General Assembly. This incredible and reactionary ruling endured until after the Democrats seized control of state government and the supreme court in the “Bloodless Revolution” of 1935.

The newly-elected supreme court promptly issued an advisory opinion to the governor on April 1. After considering numerous amicus briefs, this tribunal emphatically overruled the 1883 opinion of the Republican court that had found no mechanism or power able to convene a Rhode Island constitutional convention (55 R.I. 56). The Democrat-controlled tribunal headed by Chief Justice Edmund Flynn, advised Governor Green that such power resided in the General Assembly under the residual powers clause of the 1843 constitution (Article IV, Section 10). Because the General Assembly had authorized the call of several conventions under the Charter regime (viz., 1824, 1834, 1841, and 1842), it could continue to do so using its residual powers, namely: “The General Assembly shall continue to exercise the powers they have heretofore exercised, unless prohibited in this [1843] Constitution.”

Having the ability to summon a convention was not equivalent to the ability to structure an effective and objective gathering of delegates. Here the victorious Democrats squabbled and divided. Idealists among them, led by Quinn, insisted upon a balanced convention containing an equal number of delegates from each party; partisans led by Governor Green structured the 1935 convention act to ensure Democratic control. Rural Democrats feared that a convention would devise a reapportionment plan that would strip them of their influence in state affairs. In the face of such disunity, the Democratic legislature did not pass the 1935 convention act that had generated the new supreme court’s advisory opinion.

In 1936, the effort was renewed with the introduction of a convention bill backed by Governor Green. Like the 1935 measure, it contained no provision for a popular vote on the question of holding a convention; it was partisan in nature; and it would give the convention unlimited power, including the power to redistrict the state. Strong opposition at once developed, and it became evident that no bill which could enable a convention to propose sweeping reapportionment would pass the closely divided Senate.

In the 1930 federal census Providence, with an official population of 252,981, had 36.8 percent of the state’s population of 687,497. Any constitutionally-mandated apportionment based upon the “one man-one vote” standard would endow the capital city with well-over a third of each house of the General Assembly. This prospect alarmed not only rural Republicans, but also Democrats from other municipalities. An increase of Providence senators from one in 1928 to eighteen in a fifty-member upper chamber was alarming, unless you were a Providence voter or politician.

In the face of such opposition, legislative leaders devised a strategy. Since the supreme court had declared in its advisory opinion that only the people could restrict the scope of a constitutional convention, the proponents of the convention had to choose either an all-powerful body called into existence by the General Assembly (which could not restrict its scope) or a convention circumscribed by the people via language of limitation inserted in the popular referendum authorizing the convention call.

The legislature chose the popular-vote alternative. It amended the convention bill to provide for a special election on March 10, 1936 (less than two months after the bill’s passage) to elect delegates and to decide whether or not to hold a convention. The one restriction to be placed on the power of this body was clearly stated: the convention was to be “so limited that the present number of senators and representatives in the General Assembly of no city or town shall be decreased.”

The Republicans campaigned vigorously against the convention, electors in the small towns remained apprehensive of change, and the disunited Democrats (Quinn excepted) did not efficiently mobilize the vote (although they added referenda to the March ballot creating two new compulsory holidays–New Year’s Day and Columbus Day–to attract Italians and other working-class voters to the polls). The long-sought gathering was decisively aborted; 88,407 voters approved, but 100,488 rejected the convention act. With the defeat of The Constitutional Convention That Never Met (as Rhode Island native and Harvard law professor Zechariah Chafee, Jr., called it in two pamphlets describing the project’s fate) Rhode Island resorted to the limited constitutional convention device to effect change from the 1940s to 1973. This procedure circumvented the cumbersome amendment process placed in the constitution by its conservative Law and Order draftsmen.

Quinn’s aspirations for a constitutional convention were far broader than a modest Senate reapportionment that balanced urban and rural interests. In February, 1936 as he stumped the state to advocate passage of the convention referendum, he listed such projected benefits as permanent voter registration, home rule for cities and towns, independence of the judiciary from the legislature (an ironic proposal for the architect of the court’s 1935 reorganization), “a government of separated powers” with three distinct branches, a ban on dual office holding, budgetary power for the governor together with a line-item veto, simplification of the amendment procedure, popular initiative and referendum, and a property tax exemption for homeowners to the extent of $3,000.

Unfortunately for Quinn, even his running-mate Green backed away from his earlier support for a convention. As the governor’s laudatory biographer Erwin Levine admits, Green got Republican leaders to support his legislative agenda by abandoning his support for a constitutional convention. When Green stepped back, his bills were passed.

Quinn’s recommended reforms were broad, indicating his deep dissatisfaction with the current constitutional system. As I have shown in my book Neither Separate Nor Equal: Legislature and Executive in Rhode Island Constitutional History (1999), the 1843 constitution that emanated from the Dorr Rebellion was drafted by the Law and Order coalition that vanquished Dorr, and it was based upon Whig political theory. As such it exalted the power of the General Assembly and left the governor constitutionally weak.

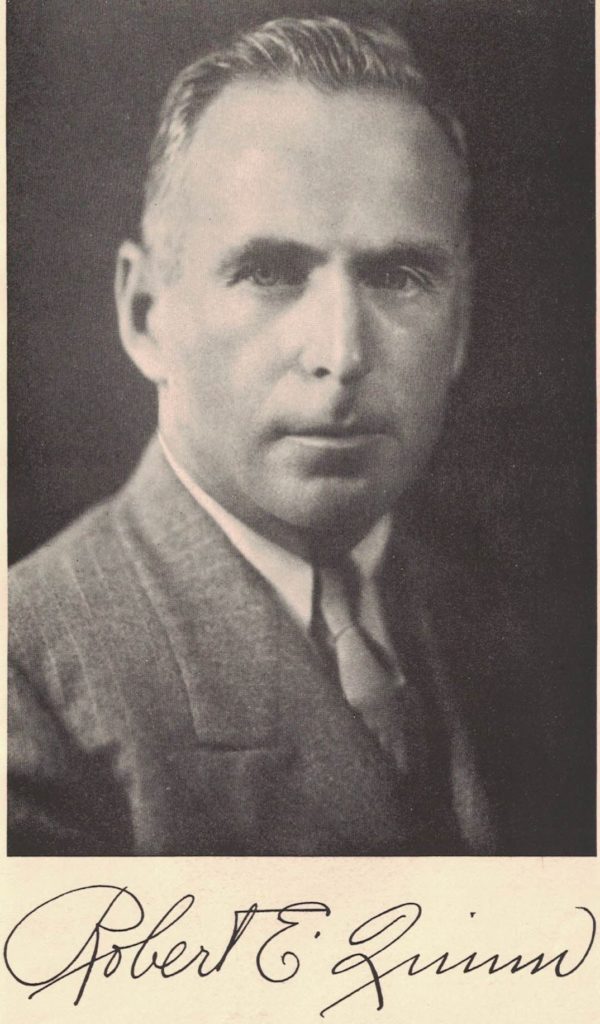

Robert E. Quinn’s official portrait as governor of Rhode Island (1937-39) by J. C. Allan Carr, hanging in the Rhode Island State House (Rhode Island State House Collection)

Quinn’s sweeping proposals sought to change Rhode Island’s constitutional order. Like reformers Thomas Wilson Dorr, Charles E. Gorman, and Amasa Eaton, he failed; but, like theirs, his position has eventually prevailed. In 1951, the Home Rule Amendment was added to the state constitution; in the 1960s the U.S. Supreme Court in three major decisions mandated the states to reapportion according to the “one man, one vote” principle thus ending rural control of the Senate. As delegate and secretary of the 1973 limited constitutional convention, I drafted and sponsored an amendment (now Article XIV) that not only streamlined the amendment process, but also provided a mechanism for the call of future constitutional conventions. After its ratification, I received a congratulatory phone call from Judge Quinn.

The 1986 Constitutional Convention made the governor’s budgetary power constitutional giving permanence to the 1935 statute enacted by the “revolutionaries.” In 1994, an amendment took the election of Supreme Court justices from the General Assembly’s Grand Committee and placed it in the hands of the governor, acting in response to the recommendations of a Judicial Nominating Commission. It also gave those justices life tenure (i.e., “during good behavior”). Finally, in 2004, after a long battle by reformers, the voters approved amendments firmly establishing the principle of separation of powers that not only vacated the legislature’s role on all state boards and commissions, but also unwisely repealed the legislature’s residual powers clause (Article VI, Section 10).

Only Quinn’s Great Depression-inspired limited tax exemption for homeowners, voter initiative, and a line-item veto for the governor have not been implemented. His drive for constitutional reform had been his obsession.

Topping Quinn’s list of legislative reforms were a personal income tax that he called “the fairest form of taxation that could be devised” and a primary election law to blunt the influence of party bosses in selecting nominees for political office. Neither had a chance of passage during Quinn’s brief and turbulent incumbency, but, here again, he was eventually vindicated. In 1947, Rhode Island legislators enacted a comprehensive direct primary system and in 1971, Governor Frank Licht, at great expense to his popularity and political future, sponsored the enactment of a state income tax.

The one major triumph registered by Quinn in 1936 was his election as governor. He led the victorious slate of the five Democratic candidates for general office by outpolling former Republican attorney general Charles P. Sisson 160,776 to 137,369. Quinn replaced Governor Green who had moved on to the U.S. Senate by defeating incumbent Jesse Metcalf, a popular and philanthropic businessman 149,146, to 136,149. The 1936 election, however, was a mixed blessing for Quinn. In reaction to this daring flip of the Senate in January, 1935, the voters returned the upper chamber to Republican control by a lopsided margin of 27 to 15. A revengeful Senate (that included previously disqualified Wallace Campbell of South Kingstown) could, and did, block Quinn’s legislative agenda.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Uneasy is the head that wears the crown. Soon after his inauguration, Governor Quinn entered into a bitter feud with racetrack mogul Walter O’Hara and his ally Mayor Tom McCoy in a confrontation reporter Westbrook Pegler and Life Magazine described for a national audience on November 8, 1937 as “The War of the Wild Irish Roses.”

In the fall of 1937, Narragansett Park became the focal point of the bitter Democratic Party factionalism that had vexed state politics since the Bloodless Revolution of January, 1935 brought that hungry party to power. Narragansett Race Track impresario Walter F. O’Hara had made huge donations to both major political organizations and employed numerous state legislators and party regulars in lucrative part-time posts at the track. He repeatedly lobbied for more racing dates and sought to limit the state’s take of the betting handle. Intensely partisan but highly principled, Quinn resented what he viewed as O’Hara’s baneful influence on state government. When Quinn succeeded Green as governor in January 1937, the stage was set for a showdown between these two extremely combative Irishmen.

Former newsboy O’Hara had acquired two newspapers (the Pawtucket-Star and Peter Gerry’s Providence Tribune), which he merged in 1937 to create the Star Tribune. When Quinn intensified state surveillance of the track’s operation (with the enthusiastic backing of the moralistic Sevellon Brown’s Providence Journal), O’Hara declared war on Quinn in the pages of the Star Tribune and strengthened his relationship with Mayor Thomas McCoy and House leader Harry Curvin, two of Quinn’s intraparty rivals.

The smoldering resentments ignited on September 2, 1937, when O’Hara’s guards beat and forcibly ejected Journal reporter John Aborn from the track. Quinn ordered his supporters on the State Racing Commission to investigate O’Hara’s long train of abuses and to rescind his right to operate Narragansett Park. When the commission promptly complied, McCoy used his influence with the new state supreme court (he had secured the appointments of Francis Condon of Central Falls and Chief Justice Edmund Flynn) to have the Racing Commission’s ruling quashed. Quinn countered by directing the commission to cancel Gansett’s fall racing dates, but once again the high court blocked the move. Meanwhile O’Hara let loose a barrage of libelous charges against the governor including a headline implying that Quinn had “landed in Butler’s,” a private mental hospital in Providence.

“Battling Bob” Quinn recklessly refused to be deterred. On October 16, 1937, one day after the second supreme court ruling and two days before the park was scheduled to open, he issued a proclamation declaring that the track and its environs were in a state of insurrection, thereby justifying the establishment of martial law. Three hundred national guardsmen armed with machine guns, joined with state police to cancel the Fall meet. McCoy and Curvin, who doubled as Pawtucket’s public safety director, dispatched the Pawtucket police to the track, but they wisely backed off. Reporter John Kieran of the New York Times observed that “In O’Hara’s case, they have sent more armed troops after one little man than against any other individual since [Mexican rebel] Pancho Villa was in his prime.”

During the Race Track War, military force had been augmented by a contentious and embarrassing legal battle where charges were hurled by each side like mortar shells. On September 9, immediately after O’Hara published his inflammatory and deceptive Butler headline, Quinn leveled the dubious charge of criminal libel against him. He was quickly arrested on that count and just as quickly bailed out by Mayor Tom McCoy; so O’Hara returned to his penthouse atop the Narragansett Park grandstand to continue the battle.

Then, while the criminal case was pending, Quinn sued O’Hara in a $500,000 civil action to which O’Hara responded with a $500,000 libel suit of his own, charging that the governor had unjustly and falsely called him a “racketeer” who had “imported thugs and gangsters into the state.”

Robert E. Quinn, governor of Rhode Island for one term, from January 5, 1937 to January 3, 1939 (Rhode Island Manual)

On October 20, Quinn delivered a radio address to the people of Rhode Island justifying his use of military force at the track and condemning the “corruption” he had uncovered in the track’s activities, especially Narragansett Racing Association’s lavish and illegal contributions to various politicians, most of them Democrats, to gain favorable terms for the park’s operation.

On November 12, Quinn’s allegations were made more specific when U.S. Attorney General J. Howard McGrath used a federal grand jury probe to indict O’Hara, his vice president, James E. Dooley, the Narragansett Racing Association, William A. Shawcross, chairman of the Democratic State Committee, and its former chairman, Thomas A. Kennelly for violation of the federal Corrupt Practices Act by making or accepting illegal political donations of approximately $100,000. Again the basis for these charges was questionable, because the alleged wrongdoing was a state matter. Nonetheless, they indicated Quinn’s beliefs in principle over party and morality over monetary gain.

Like most legal actions, these matters lingered. Then, on April Fool’s Day 1938, O’Hara made an amazing apology to Quinn. One news account stated that “the apology was so abject as to be startling.” O’Hara admitted that in “my newspaper” and “over the radio” he had made untrue statements “to serve my own purpose” and “publicly avowed” that he never paid any money to Governor Quinn in any capacity.

After this profound mea culpa, the “war” dragged slowly to a conclusion. O’Hara was out as Association president, and Quinn would soon be out as governor. All charges civil and criminal were eventually discontinued. This “tempest in a teapot,” together with a “map of the territory in insurrection” has been analyzed and criticized by Harvard professor and attorney Zechariah Chafee in a 165-page treatise published in late 1937 entitled State House versus Pent House: Legal Problems of the Rhode Island Race Track Row. Chafee concluded that this bizarre incident revealed to Rhode Islanders “long-standing and long-suppressed infections” in the body politic that cry out for sweeping ethical reform.

The brawl with O’Hara was “Battling Bob’s” final main event. Because of his enormous and positive impact on Rhode Island politics, this diminutive gladiator–he was only 5’4″ in height in contrast to his lofty stature–could have been called ”The Little Giant” had not Abe Lincoln’s adversary, Senator Stephen Douglas, preempted that soubriquet.

Quinn won this bizarre battle, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. The national embarrassment to Rhode Island caused by the “Race Track War” contributed to his defeat in 1938 by William Vanderbilt, a contest in which he ran ten thousand votes behind the remainder of the Democratic ticket. O’Hara suffered greater wounds: he was ousted as president and manager of the Narragansett Racing Association by its stockholders; his newspaper went into receivership (after which the Journal acquired and destroyed much of the Star Tribune’s equipment); and he was indicted for illegal use of corporate funds (though these charges were later dropped). On February 28, 1941, O’Hara died on Route 44 in Taunton, Massachusetts as a result of a spectacular head-on auto crash that abruptly ended his turbulent career.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Newport millionaire William H. Vanderbilt–an avid horseman and the eldest son of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, who had perished with the Lusitania–rode to the rescue of the recently deposed Republican party in the 1938 election. Helping Vanderbilt’s candidacy was the nationwide recession of 1937, which severely shook public confidence in the New Deal, as well as the scandalous Race Track War, which critically damaged the image of Governor Quinn and the local Democratic party.

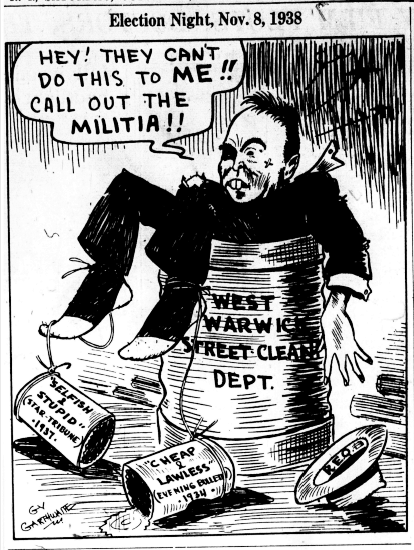

This cartoon appeared after election day in November 1938, when Quinn was defeated in his bid for re-election, losing to Republican William H. Vanderbilt III (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Seizing the opportunity to regain power, the GOP nominated the honest, willing, and prestigious Vanderbilt to battle Quinn. The socialite, who had served several terms as senator from Portsmouth, prevailed (167,003 to 129,603), leading a Republican landslide at every level–the general officers, the Senate and even the House. In heavily Democratic Providence, John F. Collins, running as a “Republican, Independent Citizens, Good Government” candidate handily beat twelve-year Democrat incumbent James E. Dunne.

There was one notable exception to this string of victories, the Pawtucket mayoralty, where Thomas McCoy actually increased his 1936 margin of victory. In fact, the boss polled more ballots in some city districts than there were registered voters! Later, at a communion breakfast, while a state criminal probe of this phenomenon by GOP attorney general Louis V. Jackvony was underway, McCoy wryly explained the secret of his political survival: “We’re politically sophisticated in Pawtucket. Elsewhere they use arithmetic to count votes; here we use algebra.”

Vanderbilt, the righteous “boy governor” (he was thirty-six when elected) was determined to bring the arrogant McCoy to justice. Despite his successful support of a state merit system law in 1939, ostensibly a positive achievement, but one that denied Democrats the unfettered access to government jobs that the GOP had long enjoyed, Vanderbilt became ensnared in a wiretap controversy during his overzealous attempt to implicate McCoy in vote fraud. In 1940 the Democratic tide rolled in once more–this time for a long stay.

United States District Attorney J. Howard McGrath, who had made political hay with Vanderbilt’s federally illegal wiretap, won the governorship and took a giant step upward in a political career that would include several high national offices including Democratic national chairman and attorney general of the United States. Congressmen Aime J. Forand and John E. Fogarty also launched long and successful tenures in that 1940 campaign, as did Dennis J. Roberts, who became mayor of Providence under a new municipal charter that strengthened the powers of that city’s chief executive. For the Democrats, happy days were here for the first time since the early 1850s, except for the intransigent Senate where the GOP held a six-vote edge. Meanwhile. a disillusioned, embarrassed, and bitter Vanderbilt rode off into the sunset, seldom returning to Rhode Island after his 1940 electoral defeat at the hands of his legal tormentor.

J. Howard McGrath won back the governorship of the state in 1941. He served as the state’s wartime governor, from 1941 to 1945. He later served as Attorney General of the United States from 1949 to 1952 (Rhode Island Manual)

Quinn paved the way for a new generation of Democrat leaders. Shortly after that party returned to power in January 1941, Governor McGrath appointed Quinn a justice of the Superior Court. After several months on the bench, Quinn took a patriotic leave of absence (as he did in World War I) to serve in the Navy’s legal branch. During his four-year tenure, he rose to the rank of captain. Much of his service was in the Pacific theater where his specialty was developing an expedited method of processing court-martial trials. He was cited both by the Navy and the Army for distinguished service as a veteran of both World Wars.

Upon his return to Rhode Island in 1945, Quinn gave some thought to a run for U.S. Senator, but his base had evaporated. He returned reluctantly to the Superior Court bench. However, his wartime experience brought him a change in venue. In 1951, Congress approved a new three-member U.S. Court of Military Appeals to which Quinn was nominated with the recommendation of U.S. Attorney J. Howard McGrath. The Senate confirmed Quinn as its first chief judge. He held this position he held until 1971, although he continued to serve on this panel, until a month before his death in May, 1975. Highlights of his judicial tenure are discussed herein with Matt Smith; however, Quinn’s court career is beyond the scope of this introduction which focuses only on Rhode Island’s turbulent decades of the Twenties and Thirties and the state’s political transformation during that period.

At Quinn’s death he was survived by his wife, Mary; two sons, Robert L. Quinn and Cameron P. “Ronnie” Quinn, a state amateur golfing champion based at West Warwick Country Club; three daughters, Norma, Penelope, and Pauline; a sister, Dr. Maisie E. Quinn, who was a legendary Kent County educator; and twenty grandchildren.

Bob’s mentor, Colonel Patrick Quinn, predeceased him in March, 1956 at the age of eighty-six. The colonel had partially transitioned from his hectic life as politician and trial lawyer to an officer in two Pawtuxet Valley lace mills. In his older years he had become a literal “lace curtain” Irishman. The colonel, however, still maintained a law practice with his son, Thomas. In the late 1940s, they hired and mentored a fledgling young lawyer named Joseph R. Weisberger, a future (and great) chief justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court. Weisberger recalled to me how Patrick and his nephew Bob, a frequent visitor to the office, were “excellent raconteurs” who regaled him with stories of their exploits during the raucous decades of the Twenties and Thirties.

“Fighting” Bob Quinn, was buried not far from his uncle in the Quinn Family Cemetery on the property of the West Warwick Country Club. Finally, both of these dynamic, battling Irishmen could rest in peace.

[Banner image: Members of the Rhode Island National Guard block the entrance to the Narragansett Race Track in the fall of 1937 (Rhode Island National Guard)]