Most Rhode Islanders know Roger Williams as the founder of the colony, as well as the great advocate for separating church and state. But we can also see him as a leader in economic development, certainly here, and arguably for the entire country. While he had little interest in commerce, he established a form of government that unleashed unprecedented entrepreneurship.

The Preacher’s Journey

Williams certainly was an unlikely champion of economic anything. Born in England in 1603 to a skilled tailor, he preferred his studies, where he excelled enough to become apprentice to the great English judge Edward Coke (pronounced “Cook”). He then entered Cambridge University, where he studied Christian theology and embraced his lifelong vocation as a preacher.[1]

He took on the Puritan perspective, seeing the established Protestant Church of England as corrupted by its movement back toward Catholicism. He and other divines sought to purify the church, but found themselves harshly persecuted by Church of England leaders during the reign of King Charles I. In fear of his life in 1631, Williams, with his wife, fled to the colony of Massachusetts, where earlier Puritan refugees had established Boston and other towns.

Williams came well recommended and was offered a plum position as preacher in a large Boston church. But he declined, having found even this establishment to be insufficiently purified of Catholic influence—perhaps because the authorities feared a full purification risked the colony’s royal charter. For the next few years, he and his young family moved from Boston to Salem to Plymouth and back again, making connections with native tribes along the way.

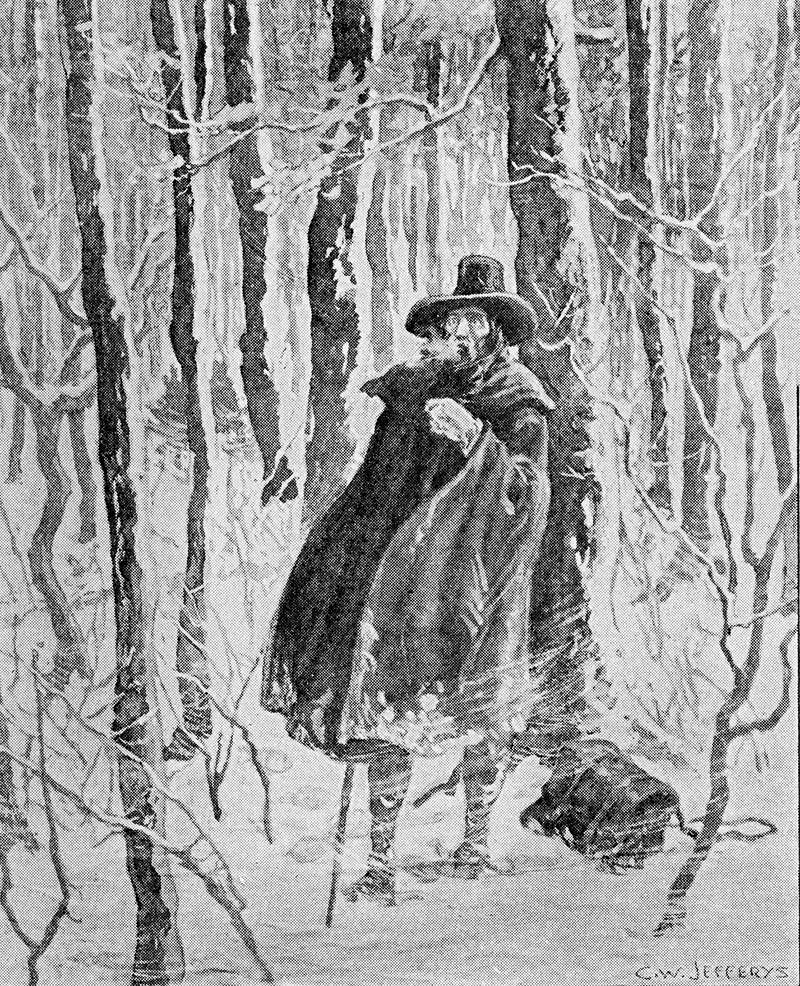

Roger Williams arriving at Providence. He was allowed to establish Providence by Narragansett chieftains (Rhode Island School of Design Museum)

Eventually Massachusetts authorities, despite their respect and affection for Williams, decided he was a dangerous influence in their fledgling divine commonwealth. In January 1636, they sent officers to arrest him and put him on the next ship back to England, which for Williams in his home country likely meant torture and death in prison. Williams, getting advance word, fled through the snowy wilderness and found refuge in a Wampanoag village. Eventually he and a few followers made their way across the Seekonk River and founded Providence, outside of Puritan jurisdiction.[2]

In organizing the new settlement, Williams insisted on no established church. People of every faith, or none, were welcome as long as they kept the peace. (Catholics were a longtime exception for political reasons, as they were assumed to be a fifth column for the sinister monarchies of continental Europe.) Williams wanted his colony to be a haven for individuals “of distressed conscience.”

The Crucial Move to Individualism

For religious, not economic reasons, Williams therefore insisted on a complete separation of religion and civil government. Having twice fled authorities intent on killing him for his theology, he sought a government focused on secular matters. That decision, supported by fellow settlers who had likewise escaped Puritan persecution, was a revolutionary break from millennia of social development.

In effect, Williams helped to lead the great second wave of civilization in the Western world. As Robert Wright has pointed out, the first wave, from the dawn of society, had been to figure out how people could live together as strangers. The early hunter-gatherers had organized into separate clans of extended families in sparsely populated areas. As wild food supplies ran out and the clans multiplied, terrible battles ensued, with extraordinarily high rates of violence.[3]

Eventually these clans surrendered oversight to “big men” or chiefs, and they tilled the land to increase the food supply. No one likes to be told what to do, but the advantages of hierarchical life were just too great. Over time, as happened in medieval Europe, these tribal communities combined into organized states, or “leviathans.” Exalted rulers collected large-scale bounty from those advantages and spent most of their time resolving disputes and allocating scarce resources. In the Hawai’ian language, for example, the word for law initially meant, “pertaining to fresh water.”

With order provided by these rulers, later called barons, dukes, and other lords, especially under feudal allegiance to a king, people could live safely in close quarters with strangers. Yet those practical advantages were not enough; religious authority was essential, to give leaders the credibility to overcome disputes and promote peace. “Hierarchy,” after all, originally meant “rank in the sacred order.” Where that transition had not fully taken place, as in pre-Plymouth New England, persistent conflict (exacerbated by European disease and technology) left the scattered villages of the Native peoples vulnerable to the new white settlers who had accepted a leviathan.

For thousands of years, humanity had thus worked to centralize power in groups greater than the clan, a process that promoted peace while fostering slow economic development. Now Williams, bolstered by his own life experience, was saying something radical: we do not need such strong government. We can live together peacefully without giving rulers control over religion, and individuals can follow their own personal inclinations. Governments could still enforce civil laws, but they should leave religion alone. Williams believed that civic strength came mainly from individual participation in government—a “bottom up” viewpoint rather than top down and from divine authority.

Roger Williams imagined as trekking through forests after being banished by Massachusetts, walking towards what is now Rhode Island

For many people in Massachusetts and elsewhere, that made no sense. Having built up a strong bulwark against violence in the religiously based state, why take away a crucial element of its power? As the National Park Service’s pamphlet at the Roger Williams National Memorial in Providence puts it, “They believed religious freedom and civil order could not co-exist.”[4]

Williams insisted that society could function well enough without a divinely approved government, and Rhode Island became his test case. Unlike in Massachusetts, heads of households voted directly for the decision-makers in government. The colony almost fell apart, as anarchy was a real risk, but it survived as a separate unit. And Williams was on to something, as the future state became a force for industrial economic development worldwide. Williams was, then, one of the first liberals, in the classical sense of the term, and perhaps the first actual founder of a liberal polity.[5]

Later writers went on to articulate and broaden this liberalism, from Montesquieu to Adam Smith, but pre-Enlightenment Williams was an early practitioner. Some historians have seen Williams as an innovator only in separating church and state, but he went much further. As Edmund Morgan wrote, “however theological the cast of his mind, Williams wrote most often, most effectively, and most significantly about civil government…. In evicting God from the proceedings, he took a step that was all but incomprehensible to his contemporaries…. He put human society in a new perspective.” Not only did Williams become an exemplar to all those later Americans who confronted state power, he directly influenced John Locke, whose writings were the main influence for the founders of the United States in the 1780s.[6]

What lay behind this radical move? How did he arrive at such ideas as “soul liberty” and freedom of conscience? Governments had overreached before, and the people they banished had not sought a liberal state. Even the Pilgrims in Plymouth, who were outright separatists, insisted on a religious government in 1620.

It is true that England had only recently begun to shake off the medieval Great Chain of Being, a mindset that had encouraged everyone to feel themselves as mere contributors to a grand divine order. That shaking off was the start of liberalization, but as usual, only crises could provoke deep change.

As a young man, Williams had a front-row seat to the abuse of power by self-absorbed rulers. First King James, and then his son Charles I, tried to centralize power. Edward Coke (1552-1634) courageously resisted both monarchs, insisting that the liberties of individual Englishmen, not just property rights, trumped even the King’s wishes. He famously said, “Shall I be made a tenant-at-will for my liberties, having property in my own house but not liberty in my person?”

Even when the King forbade the Parliament to speak of anything but raising taxes, Coke and other members refused to be intimidated and continued to protest. King Charles’s father had already put Coke in prison in 1621-22, so Coke knew the dangers, but even in his advanced age, he refused to buckle.

Also contributing to Williams’s individualism was Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the great polymath. Bacon insisted on a proto-scientific method in understanding the world, rather than traditional categories and assumptions. While Williams opposed Bacon’s royalist politics, he read his writings on knowledge and embraced his remarkable openness and curiosity.[7]

Once settled in what would become the colony of Rhode Island, Williams’s openness, combined with his extraordinary self-confidence, did more than found a liberal government. It also fostered his sensitive policy of respect and accommodation to the local Native tribes.[8] He could afford to be curious about other people when he saw them as no threat to the workings of his own conscience—his preoccupation—and when his new colony did not depend on religious conformity. For him, the New World was a tabula rasa, free of many of the old structures.

Here he took advantage of the open land around Narragansett Bay, which coastal tribes had largely abandoned due to rampant disease contracted from European fishermen. The Narragansett tribe was starting to take over those lands, but readily allowed Williams and other English to build settlements in hopes of gaining allies against their traditional enemies.

The new colony’s reputation for religious diversity and disorder (Puritans called it “Rogues’ Island,” while the Dutch deemed it the “sewer of New England”), also meant that few people from England or elsewhere settled there. There was so much land (even if owned by Indians tribes) to go around that the inevitable land disputes, while rampant in the early decades of the colony, weren’t enough to undermine the colony.[9]

Individualism in Action

We can go deeper still, to understand Williams’s perspective. Start with a remarkable point he made in a 1636 letter to his friend John Winthrop, a leader of the Massachusetts Bay colony that had just banished him. Winthrop had warned him of the posse gone to arrest him, yet Williams had his eyes on a bigger prize. He said, “I desire not to sleep in security and dream of a nest which no hand can reach. I cannot but expect changes, and the change of the last enemy, Death.”[10]

Winthrop, for his part, devoted his life to building a truly devout commonwealth in Massachusetts. For him, Williams’s liberty, the freedom to do what one chooses, was evil and corrupt. True liberty meant “liberty to that only which is good, to quietly and cheerfully submit unto that authority which is set over you.”[11]

Both of these perspectives initially deepened, rather than moderated. Soon after banishing Williams and seeing his tiny settlement just outside their jurisdiction, Massachusetts insisted ever more aggressively on conformity. This intolerance sent more refugees to Rhode Island, such as Anne Hutchinson and William Coddington. But it also so alienated supporters back in England that King Charles II later agreed to the radical autonomy that Williams sought—Rhode Island’s unprecedented charter of 1663.[12]

As for Williams, he could not even stay in a church he himself designed – he quit the First Baptist Church in America soon after co-founding it in 1638. He excelled as a preacher and diplomat, but lacked the ambition needed for sustained organizational work.

So, his daring step undoubtedly required courage as well as self-confidence. He gave up the hard-won security of religious government in order to try something quite new. His position came from the heart, as we can see in his initial decisions for the new colony.

Most notably, he laid out the settlement of Providence quite differently from the pattern in Puritan Massachusetts. There, most villages started from a central green area, good for pasturing cows, with houses and other buildings going up around it. It was also good for neighbors keeping an eye on each other and making sure they did not stray from the Puritan path. The layout promoted both community and conformity. It makes for a charming setting now in many New England towns. But in Providence, Williams laid out individual plots in a row along what is now North Main Street. Each householder received a long strip of land, fronting the Moshassuck River then rising up the future College Hill toward Benefit Street. People faced not each other, but a waterway.[13]

Roger Williams laid out Providence’s first home lots up what become College Hill. He offered equal allotments of land to all settlers, paving the way for increasing the percentage of men eligible to vote. Unusual for the time, two of the first nine lots were allocated to women, Alice Daniels and Margery Reeve. (Roger Williams National Memorial Park)

What is more, Williams, as the purchaser of the settlement, could have followed other pioneers in the New World and demanded extra land for himself. He could have pocketed the money from land sales from arrivals and set himself up as a mighty leader. Instead, he took only enough money to cover his expenses, and gave the rest to a town fund for future needs (though he did give himself a plot near the village well).

Unlike commercially minded Rhode Islanders, such as his nemeses William Coddington and William Harris, Williams had no interest in becoming rich or elite. He was too busy seeking connection to God. His lack of worldly ambition made him a poor ruler when settlers throughout the colony made him governor. He had no ambition to lord over others.

Liberalism over Commerce

While Williams never “went Indian,” he argued publicly that the King of England had been wrong to grant land to settlers where the Narragansett and other peoples lived. Caught up in religious and political questions, he was unusual among settlers in having little concern with commerce. He did open a trading post at Cocumscossuc, outside of what is now Wickford, which netted his family a decent living of one hundred pounds a year. But he seems to have used the post mainly as a base for conversations with local Narragansetts. He denounced settlers’ “land hunger” as no better than the Spaniards’ hunger for silver and gold.[14]

Ironically, Williams’s devotion to religious matters was politically crucial for Rhode Island’s distinctive economic development. Some of the more commercially minded settlers, especially Coddington of Newport, wanted the security that traditional government provided. They sought to merge with Massachusetts or Connecticut and compromise on the church-state question. It was only religious zealots such as Williams, and Warwick founder Samuel Gorton, who forced Coddington to stand down and accept separation.[15]

Williams’s zeal also made him an effective mediator between land-hungry Rhode Islanders and the local tribes, so the fledgling colony benefitted from forty years of peace. Despite the opposition of Coddington and others, Williams’s idealistic openness united the disparate towns into a single colony with a strong charter from the king.

Besides Coddington, we can contrast Williams with his friend Richard Smith. In 1651, Williams turned over the Wickford trading post to Smith when he left for England to preserve the colony’s autonomy. Smith, for all his early opposition to Puritan strictness, worked mainly to build commerce. He was disgusted with the spotty enforcement of law under the weak colonial government. At various times, he asked both Massachusetts and Connecticut to absorb Wickford, until the Rhode Island General Assembly censured him. Then in 1675, his son and heir, Richard Smith Jr., allowed a small Puritan army (not from Rhode Island) to use the post as a staging area to massacre Narragansetts in the Great Swamp during King Philip’s War—an attack that led to the retaliatory burning of Providence.

Williams had a very different view of government. He focused not on preserving security, the longtime priority, but on promoting human flourishing. His stubborn commitment to individualism kept Rhode Island separate from its neighbors. Its great strength was its openness to individual striving, while the great weakness was what Winthrop expected, that everyone would follow their own inclinations and fight continually with each other.

Sign welcoming visitors to Roger Williams National Memorial, operated by the National Park Service, in Providence

Rhode Island was disorderly enough to discourage all but committed settlers, yet not quite so anarchic as to jeopardize the all-important charter. The disorder set the stage for the colony and state’s persistent difficulties in collaborating for progress. But it preserved Williams’s incipient individualism. He fought a lifelong battle. In 1683, the year he died in poverty, he urged his fellow Rhode Islanders to put away “heat and hatreds” and “submit to government.”[16]

Williams kept looking to the future, building on what Europeans had accomplished to make something new. For all his sympathy and respect for Indians, and for all his antipathy to Anglicans and Puritans, he always saw himself as an Englishman subject to his King, devising a better way to govern. His earnest vocation helped him keep the peace in the early settlement of Rhode Island, providing just enough order to enable the fractious settlers to explore ways to rise above subsistence living.[17]

Williams and his fellow believers in limited government had built a surprisingly solid foundation for the future. Their liberalism, in the classical sense, was essential for distinguishing the colony towards its path to economic development. As the four early settlements proved their mettle (Providence, Warwick, Newport, and Portsmouth), they attracted more people who wanted no taste of Puritan oversight. These included both religious nonconformists and people who generally chafed at authority.[18]

The result strongly differentiated the New England colonies from outset, despite their small size and similar topography. Rhode Islanders benefitted from an independent, parochial spirit that challenged conventional wisdom and practice. That individualism did have its downside, as it discouraged cooperation to achieve big endeavors. Massachusetts (which absorbed Plymouth in 1691) and Connecticut reaped the benefits of communal solidarity and the pooling of resources. Far fewer people settled in Rhode Island.

Indeed, those other New England colonies (and later states) went on to prosper economically despite rejecting Williams, especially as they shook off Puritan conformity and embraced industry. Their Puritan background led to a stronger emphasis on education, a foundation for future economic success. Massachusetts and Connecticut have been wealthier per capita than Rhode Island for a century.[19]

Yet because of Williams’s stubborn insistence on individualism, Rhode Island had its own gift: an inherent restlessness and rebelliousness against the status quo. By declining to establish a state-sanctioned church, the colony also effectively privatized religion and gave public primacy to economic self-interest. Baptists and Quakers favored personal spiritual discernment over clerical learning, unlike the Congregationalists and Anglicans who dominated elsewhere. As William McLoughlin pointed out, Rhode Islanders “turned their wits and energy toward economic survival.”[20]

Despite its small size, the state went on to pioneer in economic development, including the American industrial revolution. And the country’s political economy as a whole has moved much closer to Rhode Island-style individualism than the commonwealth-based, hierarchical approach favored by Massachusetts and other Puritan colonies.[21] With his outlandish focus on personal holiness, Roger Williams got it all started.

Notes

[1] Besides his father, who belonged to the Merchant Tailor guild that made “bespoke” clothes, his older brother became a merchant trading to Turkey and other faraway lands. So, Roger was well aware of the power of commerce. [2] Jurisdiction over the settlement of Providence is unclear. According to a letter from Williams many years later, the Narragansetts had recently conquered the Wampanoags and claimed the land. They probably saw Williams as one more tributary. The Wampanoags complained to the Massachusetts Bay authorities, claiming that the inland Narragansetts had defeated them only because they, like most coastal tribes, had been ravaged by European disease. But the Puritan authorities in 1637 were not yet strong enough to take on the powerful Narragansetts, and in any case Governor William Bradford of Massachusetts admired and sympathized with Williams. See John Barry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul (New York: Viking Penguin, 2012), 216-218. Something similar happened decades later with the settlement of Warwick, though this time Massachusetts was strong enough to send soldiers to defend a Mohegan claim against the Narragansetts. See Adrian Chastain Weimer, A Constitutional Culture: New England and the Struggle Against Arbitrary Rule in the Restoration Empire (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023). Or perhaps Providence was informal Narragansett land all along, but the Narragansetts had allowed other tribes to use it for meetings or fishing. In any case, there were no settlements anywhere near the new village of Providence, as the Narragansetts were still concentrated in the south and the Wampanoags to the east. [3] Robert Wright, Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 90-92. See also Stephen Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York: Viking, 2011), chapters 2-3. Neither of these books discusses Williams, but Wright, in chapters 12-13, does point out that large, powerful states began to decline after the Middle Ages because the disadvantages of control had outweighed the advantages of security. They were outliving their usefulness, and Williams (and Coke before him) helped to bring about the shift toward individualism. [4] National Park Service pamphlet at the Roger Williams National Memorial in Providence (hereafter “NPS Pamphlet”), which was reprinted in part in the Online Review of Rhode Island History, “Roger Williams in Rhode Island,” at https://smallstatebighistory.com/roger-williams-in-rhode-island/ (Nov. 11, 2023); also Barry, Roger Williams, 168-171. Barry’s book was the inspiration for this essay. [5] Arguably the Dutch state and even England itself were liberal polities in their own way, and liberality is a matter of degree. Colonial Rhode Island still discriminated against many people who today we fully enfranchise. But Williams had taken a fundamental step forward. [6] Edmund Morgan, Roger Williams: The Church and the State (New York: Harcourt, 1967), chapter 4; Barry, Roger Williams, 390-93. [7] Barry, Roger Williams, part 1. Bacon’s protégé, Thomas Hobbes, is the best-known early proponent of the leviathan theory. [8] James A. Warren, God, War and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians Against the Puritans of New England (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018). [9] Unlike in other New England colonies, English settlers were only a minority of the population in Rhode Island. Religious tolerance attracted people from different parts of the western world. No one ethnic group dominated, which helped ensure a weak colony-wide government. [10] Not surprisingly, as Morgan points out, Williams even denied that material prosperity was a sign of God’s favor, thus challenging what became a crucial element in economic development throughout the Protestant United States. Unlike many Puritans, he had no shame in being poor. But this position likely gained few adherents even in Rhode Island, where most settlers still sought a life above poverty. Correspondence of Roger Williams, letter dated in 1636, vol. 1; and Morgan, Roger Williams, 108-11. [11] Richard Dunn, et al., eds., Journal of John Winthrop (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), 589. [12] Perhaps more important than its intolerance was Massachusetts’s failure to convert many native people to Christianity, which had been a major goal of that colony. Williams, by contrast, was impressing the court with his Key into the Language of America. And it did not hurt that Charles II partly blamed Puritans for his father’s beheading in 1649. [13] A National Park Service marker at the Roger Williams National Memorial has a fine map of this layout, which is reproduced in the smallstatebighistory.com article and in this article. Combined with the nearby saltwater cove, Providence settlers found clams, quahogs, oysters, salmon, migratory birds, and other estuary resources, along with some flat land for farming—in other words, equal access to all the resources. While Newport has the beautiful Queen Anne Square, even that previously neglected space is notable for being centered on the governmental building, with the church and related buildings arrayed along its sides. [14] Earnings from trade with the Narragansetts were probably Williams’s main income after 1645. But he relied on his partner, Richard Smith, for the post’s commercial success. See Carl Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland (Cocumscossuc Association, 1971). Note that Williams was not blind to the need for commerce. Soon after founding Providence in 1636, he wrote to John Winthrop telling him about potential findings of gold and silver (which did not work out). Mark Peterson, The City-State of Boston (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), 35. [15] James Warren suggests that Williams’s respect for Indians was part of his motivation for resisting the Puritan colonies’ attempts to absorb Rhode Island. See Warren, God, War and Providence, chapter 7 and elsewhere. That is possible, but Williams seems to have had plenty of religious motivation separate from seeking to protect Indians. [16] NPS Pamphlet, supra. Williams was so well respected that Massachusetts and Connecticut leaders delegated to Williams the fates of many native prisoners from King Philip’s War, many of whom he allowed to be sold into slavery in the Caribbean. See Margaret Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015). [17] As for Williams’s separate project to bring Christianity to the Narragansetts, that went badly. After the Puritan massacre of Narragansetts at the Great Swamp in what is now South Kingstown, Williams tried but failed to prevent the tribe from taking revenge and burning down Providence, including Williams’s own house. But at least the Narragansett chiefs and warriors did not kill Providence’s settlers. [18] The Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies were especially concerned about Quakers settling in New England and aggressively arguing against established churches. Not only did they execute Quakers who entered, but in the 1650s they threatened to invade Rhode Island in the 1650s because it harbored Quakers. But Rhode Islanders refused to budge, probably partly because they knew Oliver Cromwell, then the Lord Protector of England, supported their position against what he saw as excessively righteous Puritans. Still, Rhode Island never completely separated church and state. The Charter of 1663 limited voting to Protestant Christians, which was held to include Quakers, but not Catholics or Jews. In the 1760. [19] I have written elsewhere on how Rhode Island and Massachusetts diverged. See John Landry, “Self-Determination in Rhode Island and Massachusetts,” Online Review of Rhode Island History at https://smallstatebighistory.com/self-determination-in-rhode-island-and-massachusetts/ (July 10, 2021). [20] William McLoughlin, Rhode Island: A History (New York: Norton, 1986), 46. [21] For the evolution of the distinct political economy in the United States, see Launchpad Republic: America’s Entrepreneurial Edge and Why It Matters (New York: Wiley, 2022), which I co-authored with Howard Wolk (New York: Wiley, 2022). Margaret Newell’s From Dependence to Independence: Economic Revolution in Colonial New England (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1998), explains how Massachusetts and other Puritan colonies had gradually accepted market-based individualism by the 1770s.