Railroads came to Rhode Island in 1835 with the Boston & Providence line, initially using crude horse-drawn carriages (looking like stagecoaches on rails). The line actually started operations several years earlier, but it took a while for it to span the Seekonk River and terminate in what is now the Fox Point neighborhood of Providence. By 1837, the trains were drawn by early-model steam engines. The B&P was established to improve travel between Boston and New York. In the early nineteenth century, reaching New York meant a sea voyage around Cape Cod and Point Judith (not a particularly comfortable or safe option at the time). The alternative was an uncomfortable and slow stagecoach ride.

As the railroads spread west from Boston, they also gravitated south. When the first railroad reached Providence, it stopped there. Travelers had to take a stagecoach the rest of the way or board a steamer in Providence. The ships went around dangerous Point Judith to Stonington, Connecticut, where travelers caught another steamer for the trip down the more tranquil waters of Long Island Sound. Even that was a dangerous option as evidenced by the disastrous fire and sinking of the steamer Lexington in 1840 when 143 died. The upstart New York, Providence and Boston Railroad, better known as just the Stonington, laid track across southern Rhode Island and through the Great Swamp north to Providence (construction of the line through southern Rhode Island was an engineering challenge for the times).

On November 10, 1837, the first train, with numerous officials and politicians on board, and with considerable ceremony, traversed the fifty miles of track between Stonington to Providence, where a traveler could continue on to Boston. This bypassed the dreaded Point Judith, eliminating three hours and much seasickness on the trip. In 1837, a station was also opened in West Kingston, known as Kingston Station or Kingston Depot—a two-mile stagecoach ride from West Kington to Kingston village. Additional depots soon popped up along the route, serving the needs of mills, farmers, and ordinary citizens.

Over the decades, more than three-dozen railroads operated across the state all transporting freight and most carrying passengers. Some were tiny branch lines, built to serve a specific industry (such as the mile and a half long Wood River Junction Railroad). Many lasted for only short periods, either fading away or swallowed up in the later 1800’s and early twentieth century by the seemingly insatiable appetite of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad.

This article is about one little Rhode Island railroad that was the brainchild of a member of one of the state’s oldest families, a prominent mill owner named Rowland Gibson Hazard. He originally built his line to serve the needs of his own business, but in the process, managed to create a quirky, modestly successful short line that survived from 1876 until the last train ran in 1981.

The Hazard family descended from Thomas Hazard who immigrated from England around 1630. Rowland Gibson Hazard was the third son of Rowland Hazard and his wife Mary Peace. By the time Rowland G. (as he was sometimes known) was born in 1801, the Hazards had made their mark as one of the major landowners in New England, at one time possessing around 1,000 acres. To put this in perspective, at one time the Hazards owned all of the land comprising the villages of Peace Dale and Wakefield, the whole of Little Point Judith Neck and the land where Narragansett Pier exists today.

Rowland G. enjoyed the benefits of an excellent private education outside the state. By 1819, back in Rhode Island, he took over his father’s Peace Dale Manufacturing Company (named for his mother). With his brother Isaac, the two young Hazards substantially grew the operation, doing a significant business selling to buyers in the South. Much of his cloth was sold to Southern plantation owners to clothe their slaves. Rowland G., based on his observations during business travels in that area by the 1850s became an ardent foe of slavery and spoke eloquently against it back in his home state. Exceptionally well read and a published writer, he was also committed to philanthropy, providing the funds to build the Town Hall in South Kingstown that still serves local residents today.

So how did Rowland G. Hazard become so interested in operating a railroad? One story is that he was a regular passenger on the Stonington line from Rhode Island to New York. For convenience, he would buy a strip of tickets. On one occasion, the conductor refused to accept one of his pre-purchased tickets saying it was good only for the day of issue. Hazard argued the point, but lost and was ignominiously set off the train in Westerly. As a member of the Rhode Island General Assembly, he later took an adamant stand against what he viewed as monopolistic behavior (including rate-setting) by the railroads. It is said this his protestations before the state’s General Assembly influenced the eventual passage of the federal Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which placed limits on the previous-free-rein of railroad operators. It was this interest and his knowledge of the commercial importance of rail transport that led him to form the Narragansett Pier Railroad to serve his own company’s needs.

In 1845, fire destroyed the original Peace Dale Mill, which had been powered by the waters of the Saugatucket River. In rebuilding, the Hazards decided to turn to coal-fueled steam boilers. Peace Dale was located beside the river about mid-way between the main rail line station in West Kingston and the village of Narragansett Pier from where coal would arrive by ship. The mill’s location required a fairly expensive and inconvenient process of wagon transport: for the coal to reach the mill from the pier and for the mill’s finished products to reach the main rail line to the northwest.

It helps here to understand that in the 1800’s the villages of Kingston, Peace Dale, Point Judith, Wakefield and Narragansett Pier were then all part of the town of South Kingstown. Narragansett would not be incorporated as a separate town until 1901.

While the Hazards were expanding their mill operations, Narragansett Pier was becoming a popular summer resort. Unlike the more staid and patrician atmosphere across the bay in Newport, Narragansett catered to the somewhat less well-off (but still wealthy) elites from Philadelphia, New York, and from as far west as Chicago and St. Louis. The New York Herald wrote of Narragansett Pier, “Heaven has many attractions but it is unpopular because of the difficulty of getting there.” The only way to reach the beach was by a dusty stagecoach ride from the West Kingston train station, not a very inviting introduction to the seashore and the growing number of hotels along the waterfront.

The fates were lining up nicely. As an economical and practical way of moving people and product (and with hopes of turning a profit in the process), the idea of a short line railroad was hatched in the fertile mind of Rowland Gibson Hazard. By this time, he had retired from the active operations of the mill, turning the business over to his two sons Rowland and John (the Hazards had the custom of naming one son in each generation “Rowland,” and so one has to keep track of who’s who in our story).

With the mill business securely in the hands of his sons, the elder Rowland G. was able to devote his full attention to the railroad project. He would continue to do so until his death in 1884. The younger Rowland followed in his father’s footsteps, serving in the state legislature and as a philanthropist, funding the town library and organizing the South Kingstown high school in the village of Peace Dale. But when it came to business the family was tight with a dollar, as we shall see.

Somewhat retiring by nature, John was not an assertive leader and tended to spend more time on scholarly pursuits, but he served as president of the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company for more than twenty-five years and also as president of the Narragansett Pier Railroad (NPRR) from 1875 to 1900.

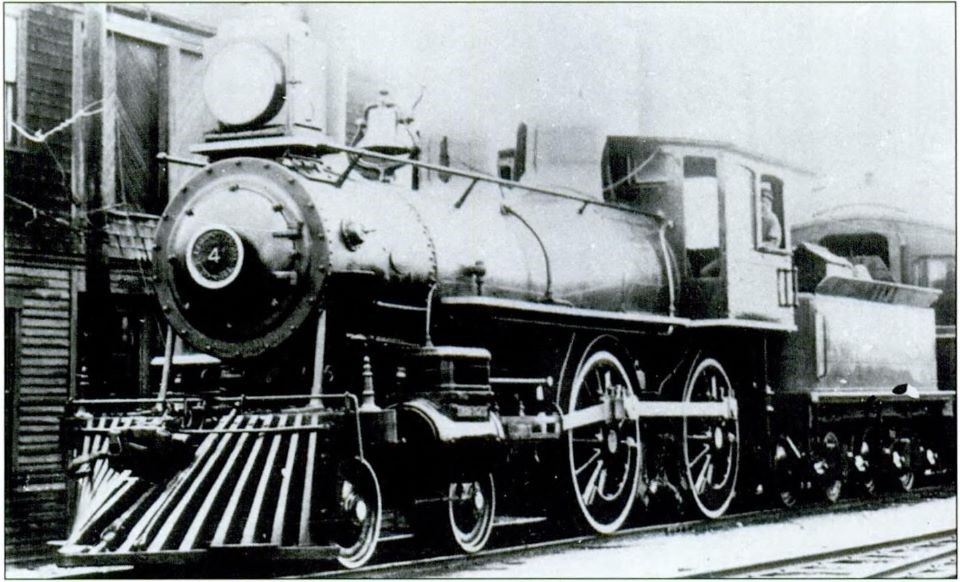

This is engine #4, the second one named Narragansett, built in 1891 and in service until it was retired in 1926

Obtaining a state charter in 1868, the elder Rowland G. got started on his railroad. He enlisted a prominent Cranston, Rhode Island mill owner, former Governor and U.S. Senator William Sprague as an investor. Surveyors laid out an eight and a half mile right of way from the main rail line through the villages of Peace Dale and Wakefield and terminating on the oceanfront at Narragansett Pier. The tracks would, of course, run right past the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company. Before construction could begin, the financial Panic of 1873 destroyed the Sprague family’s position in the company, leaving the Hazards to go it alone, until the senior Rowland lined up some additional investors.

A little sidelight here is that the proposed line, in order to minimize the grade of the roadbed, bypassed the village of Kingston, which decades earlier had also been avoided by the main line railroad. A prominent Kingston resident, Elisha R. Potter Jr., raised some $15,000 to cover the added cost of running the new rail line through Kingston. But the stockholders voted against his proposal, launching a bitter feud between the Hazards and the Potters that continued for years.

The Panic of 1873 had also set the railroad’s construction back, but by April of 1876, work by track crews was well underway. According to company records, at the time of the second annual meeting of the road’s board of directors held in May of 1876, the Boston-based Sullivan Company was working to complete construction to meet the scheduled start of service in the summer. The Sullivan Company managed to rush the road to completion in just six months. Meanwhile, the Hazards scrimped at every turn.

A classic story revolves around the contracts for the company’s locomotive and passenger cars as recounted by historian James Henwood in his 1968 book, A Short Haul to the Bay. The company had ordered rails, ties and other items, but records indicate it had to make a mad dash to acquire a number of important items it had simply forgotten. This included some key rolling stock.

It was not until mid-May of 1876 that the company rush-ordered two passenger cars from the Osgood Bradley Company of Worcester. The Hazards wanted only the best, just like the big railroads. They requested a “first class passenger car” to include the newly introduced Westinghouse air brakes. The car had a price tag of $3,700. At first, they did not want to spend additional money for such required onboard items as water coolers, lighting, or bell cords. Although these were eventually obtained, it was only after some frantic correspondence and haggling over prices. The car was lit by candles and had hard wooden seats: not luxurious but not expensive either.

Remembering the original purpose of the railroad, to deliver coal to the mill, the board also at the last minute authorized the Osgood Bradley Company to build a half-dozen coal dump cars at $280 each. The railroad also ordered a combination passenger-baggage car and even a handcar, for the right-of-way maintenance crew’s use.

There was still one piece of equipment missing: the most important. Believe it or not, no one had thought to order a locomotive. Again, the lack of actual railroad operating experience sometimes left the Hazards in the clouds. They had no idea what kind of motor power would be needed. They did know that they did not want to pay very much for it. The engine would have to overcome a slight grade along the route and be able to haul two heavy passenger cars, freight wagons or coal carriers.

The most popular type locomotive of the time was the 4-4-0 American (with four leading wheels in front and four large driving wheels). For the price of $8,000 the NPRR directors contracted with a well-known manufacturer, William Mason Locomotive Works of Taunton, Massachusetts, for a 28-ton engine with Westinghouse air brakes (why the Hazards did not use the American Locomotive Works in Providence is not known, but possibly it again came down to dollars and cents). Almost immediately the Hazards began to harass the builder for extras that had not been included in the price, such as additional pumps and even flag stands for the front end of the locomotive. The Mason Company angrily wrote the Hazards that they were already getting a cut-rate price and there would be no more free add-ons. The new locomotive, NPRR Number 1, was named The Narragansett (it was the fashion of the times to bestow a name on a locomotive). The engine arrived just in time for the road’s official opening on July 17, 1876.

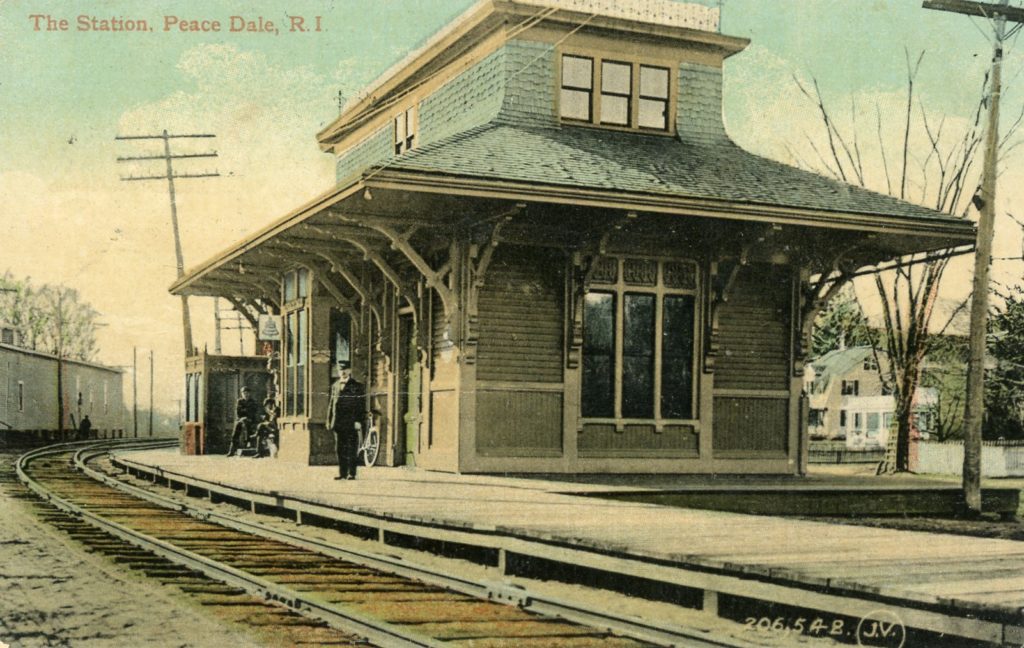

Meanwhile, the comic book tale continued. The company had also neglected to build a station in Peace Dale. For $1,500, one was quickly erected. It also hadn’t bothered with such items as benches for the depots, or switch locks and baggage trucks to handle luggage. And, it had cut corners on rails, purchasing used iron from the old Stonington line. Eventually, these wound up being used on sidings and rail yards and the line was forced to lay down heavier, more durable (and expensive) rails on its main track. A flurry of frantic letters went back and forth between Peace Dale and numerous suppliers. The line finally acquired everything needed just in time. When all was done, the cost had risen to $136,000, well above the original $100,000 estimate. The Hazards negotiated a loan (which they eventually repaid) to cover the extra expenses.

At last, on July 17, with great fanfare, the first train of two cars pulled by The Narragansett steamed out of the West Kingston station (shared with the main line railroad), around Tefft’s Hill (now a suburban residential development), past the little Gould Station on Curtis Corner Road and across a wooden trestle bridge into Peace Dale. It passed the mill complex and the new Peace Dale station, with its freight and service facilities, and continued on into Wakefield.

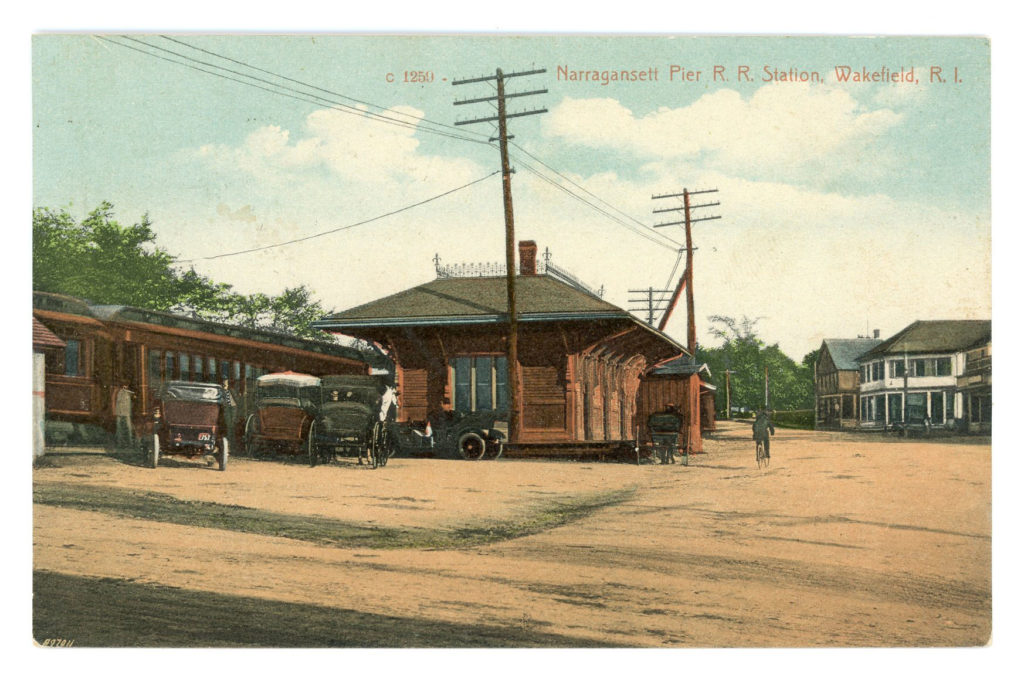

The Wakefield station was located on Robinson Street at the intersection with Main Street. Torn down in 1948 to build a row of stores, a replica depot was recently built on Main Street opposite the original site. It serves as a community room and a comfort station for the current bike trail (more about that later). A couple more miles brought the line to its southern terminus at Narragansett Pier. The original station, a turntable and roundhouse, were on Ocean Drive near the Pier Dock (now known as Tucker’s Pier).

Map showing the terminus of the NPRR at the Atlantic Ocean. The Narraganset Pier Casino (only the Towers remain today) is to the right of the railroad line

In 1896, a new station, complete with electric lighting, was built a short distance to the north on Boon Street. That building, now converted to commercial use, still stands. The line boasted an express end-to-end running time of thirteen minutes. Speeds reached as much as thirty-five miles an hour. When one thinks of how long it can take today to travel from West Kingston to the oceanfront in Narragansett, that is pretty good time.

Although some hotels had been open at Narragansett Pier since 1856, the arrival of the railroad triggered a spurt of development. All of a sudden, it was convenient and comfortable to reach one of the finest beaches in the Northeast and, with the addition of a ferry service in 1879 (also owned by the railroad and operated until 1900), to cross the bay to and from Newport. All along the waterfront, handsome wooden hotels and entertainment venues catering to vacationers took shape.

In 1883, the famous Casino opened. Designed by McKim, Meade and White, the Casino soon gained a national reputation as a destination resort, offering every luxury imaginable to the Victorian era vacationer. Narragansett Pier soon became popular with the upper middle class and the numerous day-trippers who traveled south from Providence to enjoy the beach. In the Gay Nineties the Pier was in its heyday, drawing wealthy travelers from as far away as the Midwest. The well-to-do set that visited Narragansett Pier also enjoyed the pleasures of the nearby Point Judith Country Club where championship polo matches, tennis and golf provided many pleasant hours. Special cars on the NPRR hauled the strings of polo ponies, which sometimes earned the train crews generous tips.

Sadly, the Casino was destroyed by fire in 1900, never to be rebuilt. The fire also destroyed a number of other buildings along the waterfront and signaled the end of an era. Only the Casino’s landmark stone towers spanning Ocean Drive remain today to serve as an iconic reminder of one-time glories of the Pier.

Although never a real moneymaker, the NPRR did turn a modest profit for some twenty years, serving the Hazards’ mill needs, carrying local freight and produce, and transporting numerous passengers especially in the summer. The line slowly invested in additional rolling stock and upgrading its locomotives. In 1890, company records reported that the NPRR carried more than 100,000 passengers. The railroad also held a long-time mail contract with the US Postal Service, although the Hazards regularly complained that transporting the mail was a money loser from the outset. By 1891, the company’s annual revenues reached $50,000 with net earnings in excess of five percent and the company began awarding small dividends to stockholders.

By the turn of the century, private rail cars of the wealthy would regularly arrive at West Kingston on the tail ends of New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad trains to be switched onto the NPRR track and hauled down to the Pier. The cars would be placed on a siding to await those who travelled on to Newport to return weeks or months later. The Peace Dale textile mill’s output and other local freight was carried up to West Kingston for disbursal around the country. For a short time, there was even a Sunday night sleeper car from the Pier to New York operated in cooperation with the New Haven line. According to one tale, NPRR crew members forgot to couple up the sleeper one night and was halfway to Kingston before they realized their error. They had to back up to Narragansett, pick up the car and its unhappy occupants and race back to Kingston just in time to meet the New York bound train.

There were numerous anecdotes about the line that circulated over the years. One recounted by John Henwood in his book concerned the supposed interest of the Pennsylvania Railroad in acquiring the NPRR. A telegram to NPRR President John Hazard from the Pennsylvania CEO asked about a price for the little line. It was said that Hazard wired back, “Mine not for sale. How much for yours?” (Note that Hazard used the minimum number of words probably for economy’s sake).

The NPRR carried on a somewhat tenuous relationship with the behemoth New York, New Haven & Hartford for many years. Around the turn of the century, the New Haven was the largest provider of rail services in New England (and was aiming towards a transportation monopoly in the region). The short line’s trains frequently arrived late at West Kingston, forcing the larger line to delay departures. The little railroad was also notoriously late in paying its bills to the NYNH&H. President Hazard was known to instruct his office staff to hold off payment as long as possible. That may have worked in the mill industry, but the larger railroads didn’t look kindly on that kind of business practice.

Trolley service in Rhode Island also grew rapidly in the early twentieth century. One of the better-known suburban lines was the Sea View Electric Railroad. It extended its services south to the NPRR station at Narragansett Pier (Sea View riders connected at East Greenwich with the Rhode Island Company cars to and from Providence). At first, the Sea View enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the NPRR and paid the railroad to use its tracks between Peace Dale and Narragansett Pier. The Sea View also footed the bill for electrification of that part of the line.

By this time, the New Haven Railroad was seriously flexing its muscle. The legendary investor J.P. Morgan had designs on cornering all forms of transportation in New England. He started with the New York, New Haven & Hartford. The railroad quickly got into the trolley and steamship business and gained control of other rail lines through acquisitions or alliances. With Morgan and Rhode Island trolley magnate Marsden J. Perry in cahoots, a plan was initiated to hijack the NPRR’s passengers riding from Providence to Narragansett Pier (via Kingston) and convert them over to riding the Sea View.

Under tight secrecy, the trolley line and the New Haven built an interconnection at Hunt’s River at the North Kingstown-East Greenwich line. Just before the Fourth of July weekend of 1904, the Sea View began running $1 round trip specials from Providence to Narragansett Pier. Best of all, a new Sea View station at the Pier was right at the beachfront, unlike that of the NPRR which was set back on a side street. And, the ticket price was twenty-five cents less than the NPRR could offer. The joys of an affordable day at the beach at the storied Narragansett Pier became available to a whole new audience.

John Hazard lashed back, tearing up the contract that allowed the Sea View track rights for its cars going on to Wakefield and Peace Dale. In 1907, the Sea View ran its own tracks into Wakefield down Main Street ending at the NPRR crossing where the Hazards refused to allow the trolley to cross their tracks. The two little lines were in a losing battle and the New Haven sat back and waited to pick up the pieces.

In 1911, the NPRR was briefly leased to a subsidiary of the New Haven, which planned to use the smaller railroad as a bargaining chip to keep the Canadian-based Grand Trunk Railroad from building a line to reach Point Judith (this would have ultimately brought considerable competition to the New Haven’s rail and steamship operations).

For a period of years leading up to World War I, J.P. Morgan interests operated the NPRR under a lease through the Rhode Island Company (the entity that operated trolley lines across Rhode Island). But the Hazards continued to own the actual rail line. America’s entry into the war saw federal control of train lines across the country. By the time operations were returned to private ownership in 1920, trolley lines in the state had gone bankrupt. Also Rowland Hazard III had died (in 1918), the same year the Peace Dale mill operations were sold to a large national company, M.T. Stevens & Sons. The New Haven handed back the NPRR in poor health to the Hazard family. The New Haven itself began a long slippery slope that ended with its own demise in the 1970s.

The NPRR was also stuck with the faltering Sea View trolley line. NPRR’s then President Nathaniel Bacon (a Hazard family relative) briefly tried to save the Sea View, but it was a lost cause. By the fall of 1920, trolley service was finished in southern Rhode Island and the railroad turned its full attention to its own survival.

Rail passenger service had begun to decline as roads improved and the automobile became the favored mode of transportation. The NPRR retired its aging passenger cars, hauling them out for special occasions or later for rail fan trips.

Experiments with lightweight passenger rail service began in 1920 with a genuine oddity, a ten-year-old self-propelled McKeen rail car (purchased, of course, at a cut-rate price). With its pointed nose and large circular windows, the McKeen looked like an overturned boat on wheels. The NPRR refurbished it in its Peace Dale shop and with a burst of publicity sent it off on its maiden run to Narragansett. Apparently, no one had thought about a trial run or about the sharp curve leading into the Pier station. The McKeen could not make the bend. It derailed, tearing up a stretch of track, and came to an ignominious, screeching halt. It was towed back to Peace Dale, put on a siding and never saw service again. Eventually, its remains became a snow fence on the rail line near Curtis Corner Road.

Not to be dissuaded, President Bacon ordered a Brill-Mack rail bus in 1921. This proved so successful that a second unit was soon in service and a near thirty-year span of rail bus service began. The NPRR introduced a series of small, gasoline powered rail buses, affectionately known among the locals as Mickey Dinks, named after a pair of popular motormen, Andrew “Mickey” Redmond and Leslie “Dink” Gould. Later, the NPRR also tried supplementing service with over-the-road buses on several South County routes, a venture that met with limited success until it was phased out in 1935.

In 1923, the NPRR ordered a brand new and powerful steam engine, a Mogul type 2-6-0, which became engine #11. This locomotive served the line until 1937 (and survives to this day, as our story will reveal). A used steam engine, #20, was also leased from the New Haven in 1930. There were plans to give #20 a fancy raised brass number plate on the front of the boiler, but finding out it would cost $11.00, the ever frugal Hazard family made do with a painted number on its “new” engine. During and after World War II, freight service was provided using a succession of small gasoline or diesel powered locomotives, the steam era having ended on the NPRR in 1937 when #11 and #20 were sold. Although a total of twenty-five engines serviced the line over its existence, the NPRR never had more than two or three engines in service at any one time.

World War II bought some time. Gasoline rationing and increased commercial and military traffic helped, but right after war’s end, red ink returned to the company’s books and remained there until the end.

In 1946, the Hazard family finally decided it was time to call it quits. It found a buyer for the line’s assets in the person of Royal Little, an astute Rhode Island businessman (and summer resident of Narragansett) who went on to become the founder of Textron, one of the nation’s first major conglomerates. Little’s family trust, known as American Associates, bought out the NPRR for $25,000. After some seven tumultuous decades, the Hazards’ experiment in rail service was finally over.

Nothing came of the American Associates venture except to see the NPRR further stripped. The rails between Wakefield and the Pier were abandoned and torn up in 1953 when American Associates sold the remains of the line to The Wakefield Branch Lumber Company.

The lumber company operated freight service on the remaining track between Wakefield and West Kingston. The last Mickey Dink rail bus passenger service occurred on June 21, 1952, when the only surviving bus, #36, broke its rear axle. Wakefield Branch spruced up the appearance of equipment and the right of way. But it could not make a go of things either in spite of some initial early profits fueled by contracts with a fish oil processing plant near Curtis Corner, and the transport of lumber and fuel oil to various clients on the line. When the fish oil plant folded in 1963 the red ink began to flow again.

In 1964, the NPRR was sold to a young Philadelphia investor by the name of J. Anthony Hannold, who planned to continue freight service and also develop the road into a tourist attraction, much like the present Old Colony in Newport and the Valley Railroad in Essex, Connecticut. Hannold bought a couple of vintage passenger cars from the Boston & Maine, a former Canadian National business car and converted an old boxcar into an open observation car. He offered rail fan trips and scenic excursions between Peace Dale and West Kingston into the 1970’s. Hannold tried to save money in 1967 by using a little 38 year-old Plymouth gasoline powered engine to haul his tourist trains and freight services.

When he, his wife and young children moved to Rhode Island, Hannold remodeled the Peace Dale station, restoring the first floor waiting room and creating living space for his family upstairs (which is how it remained for many years). The tourism venture lasted barely two years and died from a lack of interest from the public. Hannold continued his freight operations and managed a modest profit until he finally sold out in 1969 to Dr. John Miller, a wealthy Connecticut dentist and railroad buff. But Miller knew nothing about actually running a railroad and the NPRR’s downward slide continued. (The then eleven-year-old Christian McBurney recalls being allowed, with his younger brother Shaun, to ride the rails with a pump (hand) car, going over elevated trestles and bridges).

In 1971, the line was briefly in the hands of a pair of Illinois men, who planned to operate a school for railroad engineers on the line’s last remaining track. By then the sole assets were two locomotives, a caboose, some outbuildings along the line, and the tracks between Wakefield and West Kingston. Nothing came of that idea either. For a couple of years in the 1970’s, the last remaining employee, Peter Verges of Wakefield, ran summer excursion trains including one special event in 1975 to celebrate the line’s one hundredth anniversary.

Finally, the owner of the former Peace Dale Mill complex, Anthony Guarriello, stepped in and bought the line’s remaining assets. The NPRR continued to limp along with limited freight service, but by 1979, even that had dried up. The end came in 1981 when Guarriello at last pulled the plug. In the summer and early fall of that year, the tracks from Wakefield to West Kingston were torn up. The Church Street railroad bridge in Peace Dale was taken down and the two trestles over Kingstown Road at the Peace Dale Flat area and Rocky Brook along with the bridge over the Saugatucket River were demolished. The last remaining rolling stock was sold and shipped off. In the following years, almost all the visible traces of the line disappeared.

Today, the NPRR’s lone caboose sits shrink-wrapped in the yards of the Valley Railroad in Connecticut, awaiting future restoration. The NPRR’s Engine #11, which proudly served the line from 1923 to 1937, has a new lease on life. The engine was first sold to the Bath & Hammondsport Railroad in New York. The B&H, known as The Champagne Route because of its tracks in wine country, used the engine for passenger excursions until 1949.

But #11 wasn’t ready for retirement quite yet. The B&H stored it until 1955 when it was sold to a succession of collectors. It briefly wound up back in Peace Dale in 1977 when Dr. Miller acquired it with the intention of restoring it. The work was never completed and Number 11 languished partly disassembled in a storage building. When the NPRR was finally dissolved the engine was sold to the Middletown & New Jersey RR in Middletown, New York, where it remained until 2006 when its present owners, the Everett Railroad in central Pennsylvania, acquired it. The line’s president, Alan Maples, undertook an extensive restoration project and in 2015 the venerable 94-year #11 proudly went back in service powering tourist excursion trips on the passenger and freight short line.

Today, most of the NPRR’s original right-of-way also has a new lease on life as the William C. O’Neill Bike Path. The route starts at the West Kingston AMTRAK station and meanders through the Great Swamp, woodlands and several villages within the town of South Kingstown and currently ends at Mumford Road in Narragansett. The final one-mile phase of the bike path, when completed, will terminate north of the Narragansett Towers near the beachfront.

The NPRR’s Peace Dale station on Railroad Street, for a number of years a private home, is now a commercial property, as is the Narragansett Pier station on Boon Street. Other than that and the rolling stock mentioned above, the once proud and feisty Narragansett Pier Railroad survives only in the memories of those South County residents who can recall the mournful wail of the steam whistle as an engine led its little string of passenger cars down to the bay or the sharp bleat of the diesel engine horn as a stubby diesel locomotive shuttled a train of mixed freight to destinations down to the sea by rail.

[Banner Image: This is engine #4, the second one named Narragansett, built in 1891 and in service until it was retired in 1926]

Bibliography

Books

James N. J. Henwood, Narragansett Pier RR: A Short Haul to the Bay (Brattleboro, VT: The Stephen Greene Press, 1969)

Frank Weston, The Passing Years: 1791-1966 (Providence, RI: The Industrial National Bank of Rhode Island, 1966)

Frank Hepner, Railroads of Rhode Island (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012)

Ronald D. Karr, Lost Railroads of New England, 3rd edition (Pepperell, MA: Branch Line Press, 2010)

Joseph E. Coduri, Rhode Island Railroad Stations (Middletown, DE: Privately Printed, 2016)

Christian M. McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I. 1700-1900 (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004)

Online Sources

Edward Ozog, “Rhode Island Railroads,” sites.google.com/site/rhodeislandrailroads

“Narragansett Pier Railroad,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narragansett_Pier_Railroad

“William C. O’Neill Bike Path, Rhode Island Bike Trails,” www.traillink.com/trail/william-c-oneill-bike-path.aspx

Newspapers and Magazines

Linn H. Westcott and Paul B. Johnson, “The Narragansett Pier Railroad: A Railroad You Can Model,” Model Railroader Magazine, Vol. 41, No. 9 (September 1974)

G. Timothy Cranston, “South County’s Great Rail War,” The Independent, Sept. 18, 2014

George D. Ridgeway, “Six Miles of Fun,” Yankee Magazine (September 1965), pages 46-52

“The Peerless Pier Railroad,” Narragansett Times, October 17, 1947

“Two buy RR; plan engineers’ school”, Narragansett Times, January 14, 1971

G. Edward Prentice, “Looking Back at the Old NPRR,” Narragansett Times, Feb. 14, 1980

G. Edward Prentice, “Taps for the Pier Railroad,” Narragansett Times, Oct.1, 1981

Other

The author also acknowledges the generous assistance of the South County History Center and the Peace Dale Library.