In colonial times, death was a common occurrence reaching into all families, regardless of wealth, social station and race. In seaport towns such as Newport, Rhode Island, influenza, scarlet fever, smallpox and other infectious diseases sometimes ravaged the population, as ships would drop anchor with infected passengers. At the time, epidemics accounted for many deaths–sweeping young and old away in short order. With the frequency of deaths, funerals, proper burial measures, and cemetery visits became important routines of the living.

God’s Little Acre section within the Common Burying Ground in Newport (Theresa Guzmán Stokes and Keith W. Stokes)

Cemeteries are largely seen as final resting places, but for those interested in historical and genealogical research, cemeteries can provide a wealth of information regarding people, places and events of the past. The Common Burying Ground in Newport is one of America’s earliest public cemeteries, with a section dating back to at least 1705 that includes the final resting place of colonial-era African men, women and children. Known as God’s Little Acre, this section along Farewell Street has been recognized as having possibly the oldest and largest surviving collection of markers of enslaved and free Africans. The very existence of so many stone markers for Africans in early America is noteworthy in its own right.

When studying early American burial customs, it is important to recognize that only the privileged few could afford the luxury of providing a stone marker for their dearly departed. That so many markers were cut for both enslaved and free Africans is a remarkable testament of African identity, perseverance and memory in colonial America.

While the funerals and burials of the white population were overseen by the houses of worship, Africans would typically turn to themselves to properly manage the affairs of their own departed. In 1780, a group of African men came together in Newport to organize and charter America’s first African mutual aid society known as the Free African Union Society. The Society’s lofty mission included establishing a burial society to ensure proper funerals and burials for the larger African community.

“In Memory of Violet Hammond, the Wife of Cape Coast James who died Sept. the 3rd 1772 aged 26 years.” Cape Coast Castle was a major slave trading point for Newport captains commanding slave ships (Theresa Guzmán Stokes and Keith W. Stokes)

The African funeral in colonial Newport was as much a celebration of life as it was to bid farewell to the recently deceased. The funeral often included dancing, singing and public testimonials of the life of the recently departed. Many times, African funerals would include hundreds of African participants, as described by Reverend Ezra Stiles of Newport’s Second Congregational Church in his diary entry for May 20, 1770: “A Negro Burying, the Church Bell tolled (all our Bells sometimes toll for Negroes), a procession of Two Hundred Men and One Hundred and Thirty Women Negroes.”

In 1790, the Society promulgated a set of formal regulations to see that proper burials include both the procession to the cemetery and the proper participation of the community, both enslaved and free. In an African funeral in Newport, the leaders of the African Union Society would lead the procession from the center of town to the burying grounds with the body of the dearly departed on a wagon. The procession would be organized by a ceremonial sheriff or undertaker, a well-respected position within the African community. After the burial, the procession would return for a time of reflection and celebration of the life of the dearly departed. The burial regulations still exist today as part of the original minute book of the African Union Society, which is held in the collections of the Newport Historical Society. Dated January 14, 1790, they state:

Today, as a group of historians and civic-minded citizens under the leadership of the Newport Common Burying Ground Commission work to restore and interpret God’s Little Acre, it is important to remember that Newport’s larger Common Burying Ground was established by an extraordinary man and within a very special time and place in American history. The Common Burying Ground is a ten-acre parcel of land that was gifted to the Town of Newport in 1640 by Dr. John Clarke. A true Renaissance man, Clarke, one of the earliest settlers of Newport, would become an early Baptist minister and the man who would secure approval from King Charles II for a Royal Charter in 1663 that established Rhode Island as a British colony under the unique tenets of religious toleration and the separation of church and state. Clarke’s gift of land for an establishment of a public burying ground contained the important requirement that all would be afforded the opportunity to be buried in a common place regardless of social or religious status. As Newport grew into a major American seaport during the 18th century, so too did its population of enslaved and free Africans, who, as they departed this life, would be buried in the God’s Little Acre section of the Common Burying Ground.

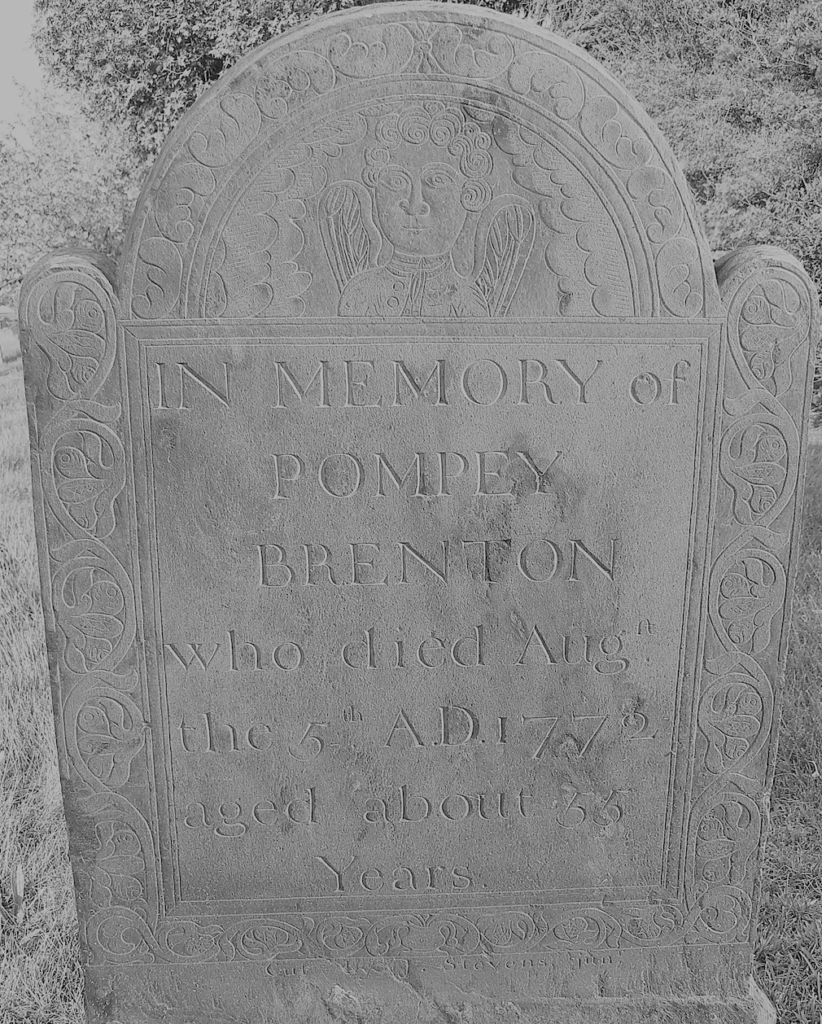

“In Memory of Pompey Brenton who dies Augst the 5th A.D. 1772 aged about 33 Years.” Slaves masters often named their slaves after famous Romans from antiquity (Theresa Guzmán Stokes and Keith W. Stokes)

The fact that Africans, enslaved and free, were buried in a separate section, but still within an ancient, historical burial ground with their own burial markers is unique and historically noteworthy in colonial America. However, recent interpreted work has found several markers of 18th century enslaved and free Africans who were buried not only in the God’s Little Acre section, but within the larger cemetery resting peacefully beside their colonial white contemporaries. This evidence of integrated burials during the 18th century offers the supposition that while the God’s Little Acre section of the Common Burying Ground was clearly designated as the final resting place for African members of the Newport community, it was not a strict requirement.

This evidence of integrated burials within an early American community, in a seaport that was the leading slave trading port in British North America before the American Revolution, offers a lesson in hope: hope that perhaps Dr. John Clarke’s belief in civic toleration may have justly influenced white masters to see their enslaved servants as something more than chattel property, at least in death.

[Banner Image: God’s Little Acre section within the Common Burying Ground in Newport (Theresa Guzmán Stokes and Keith W. Stokes)