Seth Luther was one of the most memorable figures in the early days of unionism in Rhode Island. When he died in 1863, a Providence Journal obituary said that he “had considerable talent for both writing and speaking; but he was too violent, willful and headstrong to accomplish any good” and that he had “just closed his worse than useless-life.” Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Luther was born in 1795 at Providence, the son of Thomas and Rebecca Luther. His father, a tanner, had been a soldier in the Revolutionary War. One of his brothers was a blacksmith, another a weaver and the third, a shoemaker. After a brief stint of schooling Seth Luther learned the carpenter’s trade. At the age of twenty-two he headed West in what was to become a wanderer’s life. At the end of his public career he claimed that he traveled 150,000 miles, mostly on foot in a thirty year period.

In 1832, he was in a delegation of workers that called on the Governor of Rhode Island to enlist his support for the ten-hour day. That year he traveled extensively and made speeches to rally support for the Boston strikers who downed their tools in order to win a ten-hour day. He also began writing and selling subscriptions for a labor paper called the New England Artisan. During one of his stops in Providence he was assaulted and wrote about the incident saying that with blood streaming from his face he had told his attacker “I glory in these wounds, knowing they would not have been inflicted, had I not advocated the cause of the suffering children incarcerated in the cotton mills of our once happy New England.” He especially opposed whipping as a means of enforcing the discipline of children in these mills. On several occasions he complained of being blacklisted as a carpenter because of his outspoken labor advocacy.

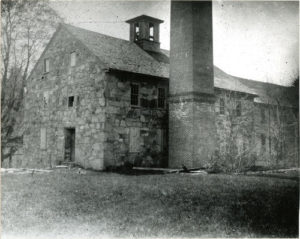

A factory for the Rhode Island Print Works in Cranston, circa 1840 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Four of his speeches were published and his style and approach are well illustrated by a comment about the pattern of industrial relations in 1833:

The whole system of labor in New England, more especially in cotton mills, is a cruel system of exaction on the bodies and minds of the producing classes, destroying the energies of both, and for no other object than to enable the rich “to take care of themselves” while the “poor must work or starve.” The rich do take care of themselves….While the daughters of these Nabobs are “taking care of themselves” while sitting gracefully at the harp or piano, in their splendid dwellings, while music floats from quivering strings through perfumed and adorned apartments, and dies with gentle cadence on the delicate ear of the rich, the nerves of the poor woman and child in the cotton mill are quivering with almost dying agony, from excessive labor, to support this splendor….

In 1834, he was one of the founders of the Trades Union of Boston and Vicinity. He was also an active member of the National Trades Union until its collapse in 1837. As the son of a Revolutionary War soldier, he often called attention to the discrepancy between the ideals for which his father had sacrificed and the realities of workers’ lives. In 1836, he made a speech at a Labor 4th of July celebration in Brooklyn where he said, “those who build houses these days have none of their own and are dependent on a ‘combination’ of landlords for shelter from the weather” while “combinations” (unions) of workers were attacked. He expressed the belief that before the Revolution colonial society had been less unequal.

In 1841, Luther got a job as a speaker for the Rhode Island free suffrage movement, organized to rid the state of property qualifications for voting which disenfranchised many workers. This movement was climaxed by the Dorr War, an unusual attempt to amend the state constitution. For his part in this episode Luther was imprisoned, first in Providence and later in Newport, where in November1842 he tried to escape by setting fire to his cell. He-was quickly recaptured but in March 1843 he was released and went on a speaking tour on behalf of the free-suffrage movement. In August of that year, after the charges against him had been dropped, he went West again and spent the winter of 1843-44 in rural Illinois. He wrote to his lawyer in Providence that “my mind had been extremely impaired by my confinement.” In the summer of 1844, he spent eight weeks in Cincinnati trying to gain support for Thomas Dorr, the leader of the suffrage movement, who was still in prison. Later he returned to Illinois but by July 1845 he was back in Providence.

In 1846, he took part in a convention held at Manchester, New Hampshire, to promote a campaign to establish the 10-hour work day. Shortly afterwards, he wrote to the President of the United States offering to enlist as a clerk in the Army or Navy for service in the Mexican War. While he was apparently accepted for military duty, he became involved in a bizarre episode that prevented him from going off to war. He was taken into custody after he had entered a Boston bank, armed with a sword and demanded $1,000 “in the name of President Polk.”

After that he spent the remaining seventeen years of his life in various asylums, including ten years at Butler Hospital. Discharged from Butler as “unimproved” in 1858, he was transferred for economic reasons to Vermont Asylum (now Brattleboro Retreat) where the cost of custodial care was cheaper than at Butler. When he died he was buried in the fifth tier of the Retreat Cemetery in Brattleboro.

That cemetery has not been maintained, and if you were to look for Seth Luther’s grave, you would not find it. No matter, for his true memorial is not some timeworn tombstone but the fact that workers in Rhode Island can vote without requirements of property ownership and are protected by wage and hour regulations far better than those for which he fought in vain. One historian called Seth Luther a “missionary” for labor and so he was, traveling far and wide in support of full citizenship and union rights for wage earners. “In my opinion,” he observed in 1836, “that mechanic or laborer who opposed Trades Unions is either ignorant, foolish or wicked. He is [heading for] a kind of suicide.” He devoted his considerable talent and energy for the rights that mechanics and laborers later achieved.

The Butterfly Factory cotton mill in Lincoln, which still stands today (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

The following are selections from An Address to the Working Men of New England, written & published in 1832 by Seth Luther.

The mills generally in New England, run 13 hours the year round, that is, actual labor for all hands; to which add one hour for two meals, making 14 hours actual labor — for a man, or woman, or child, must labor hard to go a quarter, and sometimes half a mile, and eat his dinner or breakfast in 30 minutes and get back to the mill. At the Eagle Mills, Griswold, Connecticut, 15 hours and 10 minutes actual labor in the mill are required; at another mill in the vicinity, 14 hours of actual labor are required. It needs no argument, to prove that education must be, and is almost entirely neglected. Facts speak in a voice not to be misunderstood, or misinterpreted. In 8 mills all on one stream, within a distance of two miles, we have 168 persons who can neither read nor write. This is in Rhode Island. A committee of working men in Providence, report that in Pawtucket there are at least five hundred children, who scarcely know what a school is. These facts, say they, are adduced to show the blighting influence of the manufacturing system as at present conducted on the progress of education; and to add to the darkness of the picture, if blacker shades are necessary to rouse the spirit of indignation, which should glow within our breasts at such disclosures, in all the mills which the enquiries of the committee have been able to reach, books, pamphlets, and newspapers are absolutely prohibited. This may serve as a tolerable example for every manufacturing village in Rhode Island. In 12 of the United States, there are 57,000 persons, male and female, employed in cotton and woolen mills, and other establishments connected with them; about two-fifths of this number, or 31,044, are under 16 years of age, and 6,000 are under the age of 12 years. Of this, 31,044, there are in Rhode Island alone 3,472 under 16 years of age. The school fund is, in that State, raised in considerable part by lottery. Now we all know, that the poor are generally the persons who support this legalized gambling; for the rich as a general rule, seldom buy tickets. This fund then, said to be raised by the rich, for the education of the poor, is actually drawn from the pockets of the poor, to be expended by the rich, on their own children, while this large number of children, (3,472), are entirely, and totally deprived of all benefit of the school fund, by what is called the American System.

It has been said, that the speaker is opposed to the American System. It turns on one single point: If these abuses are the American System, he is opposed. But let him see an American System, where education and intelligence is generally diffused and the enjoyment of life and liberty secured to all; he then is ready to support such a system. But so long as our government secures exclusive privileges to a very small part of the community, and leaves the majority the “lawful prey” to avarice — so long does he contend against any “System” so exceedingly unjust and unequal in its operation. He knows that we must have manufactures. It is impossible to do without them; but he is yet to learn that it is necessary, or just, that manufacturers must be sustained by injustice, cruelty, ignorance, vice, and misery, which is now the fact to a startling degree. If what we have stated he true, and we challenge denial, what must be done? Must we fold our arms and say, It always was so, and always will be. If we did so, would it not almost rouse from the graves the heroes of our revolution? Would not the cold marble, representing our beloved Washington, start into life, and reproach us for our cowardice? Let the word be —Onward! Onward! We know the difficulties are great, and the obstacles many; but, as yet we know our rights, and knowing, dare maintain. We wish to injure no man, and we are determined not to be injured as we have been; we wish nothing, but those equal rights, which were designed for us all. And although wealth, and prejudice, and slander, and abuse, are all brought to bear on us, we have one consolation — We are the Majority.

Fellow-citizens of New England, farmers, mechanics, and laborers, we have borne these evils by far too long; we have been deceived by all parties; we must take our own business into our own hands. Let us awake, Our cause is the cause of truth — of justice and humanity. It must prevail. Let us be determined no longer to be deceived by the cry of those who produce nothing and who enjoy all, and who insultingly term us — the farmers, the mechanics and laborers, the LOWER ORDERS — and exultingly claim our homage for themselves, as the

Higher ORDERS —

While the DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE asserts that

“ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL.”’

[This article originally appeared in: A History of Rhode Island Working People, edited by Paul Buhle, Scott Molloy, and Gail Sainsbury (Providence, RI: Regine Printing Co., 1983)][Banner image: Workers pose at a steam fire engine factory in Rhode Island (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]