In any war, some of the people who suffer most are almost entirely overlooked by the subsequent histories: the people who happened to live where the fighting occurred or near where the armies camped. Whether they fled their homes in the face of fighting or stayed to suffer damage and depredations, local inhabitants almost always were (and are) the greatest losers in armed conflicts. This was certainly the case during the American Revolution. In an era when armies lived largely off the land, it did not matter which side a property owner was on, or where his loyalties lay; odds were, if the front lines were nearby, the fields and barns and larders would be picked clean by soldiers who swarmed like locusts over whatever countryside they passed through.

After the conflict ended, many who had lost property made claims for retribution. This was often a difficult proposition, because the perpetrators of the depredations were seldom the ones responsible for settling such claims. Supporters of the rebellion (Patriots) certainly couldn’t make claims against the British government, and neither could those who opposed the rebellion (Loyalists) reasonably make claims against the new United States. Even within the new American nation, property owners may have suffered losses perpetrated by soldiers from a state different from their own.

One such claimant was Silas Cooke, a successful merchant and distiller in Newport, Rhode Island who, like other Newport merchants, kept a country house and farm as well. His description of his sufferings shows just how little loyalty to either side mattered when it came to the pragmatic realities of living in a war-torn location.[1] He leased and operated a farm located in Middletown, then a largely rural community on the biggest island in Narragansett Bay, now known as Aquidneck Island. On this island was the fifth-largest city in the colonies, Newport, built around an excellent deep-water harbor that did not freeze in winter. These attributes made Rhode Island strategically significant.

The early days of the Revolution were uneventful for Cooke—the fighting was far away, and the Patriot local army was small and friendly. But in December 1776 things got suddenly worse.

A large British fleet carrying thousands of troops appeared off the southern tip of Aquidneck Island and quickly pushed into Narragansett Bay. Knowing that they were far too weak to defend the island, the heavily outnumbered local Patriot troops prepared to flee the island. As they did so, they seized a cart from Cooke’s holdings along with its horse, collar, harness, saddle and bridle, as well as two head of cattle, without offering any compensation. This was not done maliciously; there were tons of military stores to be taken off the island to the mainland, and every available vehicle was required. Livestock was removed from the island to prevent the potential food source from falling into British hands. The American army surely would have returned them had they had the chance, but once British army troops landed on the island there was no going back. Cooke never again saw his cart, horse, or cattle, or received any compensation for them.

An army of over 5,000 British and German troops took up residence on the island, supported by a strong naval contingent in the bay; American troops on the mainland hemmed them in, insuring that the island was not only a garrison but a war zone. Skirmishes of one sort or another took place almost daily, while farmers on the island were faced with equally frequent incursions by soldiers. Crops, livestock, and fence rails for fuel were prime targets of opportunistic soldiers looking to supplement their rations, and the monotony of garrison life only made plundering worse.[2]

Silas Cooke’s position quickly deteriorated. The seat of Cooke’s leased farm was Whitehall, an elegant manor house that stands to this day and is open to the public. The British quartermaster officer responsible for finding lodging for the army saw it as a suitable place to house the German general commanding a brigade of Hessian troops on the island; the general, a staff officer and eight servants moved into three rooms in the house and remained for five months. Once war broke out it was common practice for armies on both sides to lodge officers in private homes, with or without the owner’s permission. The lodging was not the only inconvenience Cooke suffered at Whitehall; it was also the sixty-five cords of wood that they burned, the substantial quantity of fowl that they ate, and the 1,400 fence rails that disappeared, presumably carried off by soldiers seeking to burn the wood to warm their own quarters during the winter and cook their food. Cooke was given a receipt for the cord wood and told he’d be paid in the future when accounts were settled, a promise from a British officer who assumed, at that time, that the war would end favorably. The German general also took a “littel carte” that was never returned.

Cooke owned a vacant house in Newport. Needing places to lodge thousands of soldiers for the winter, the British quartermaster took over all vacant buildings in Newport; Cooke’s house became the home for thirty-six British soldiers until June when they could go into summer encampments. To supplement their firewood ration the soldiers removed all of the interior doors, including the locks, as well as a wash house outside. Even after the soldiers left, the house continued to be plundered for wood. The men Cooke hired to watch the house soon found Sergeant Jonathan Robertson of the 43rd Regiment of Foot and some soldiers pulling parts off the house. When brought before the British commanding officer, Sergeant Robertson denied the charge, but then confessed when proof was offered.[3] The house was, however, too badly damaged by this time and had to be torn down.

Cooke also owned a storehouse in Newport, which the British quartermaster took over for use by the army. Although it contained only a barrel of tar and a few hundred pounds of copper, these items disappeared. Cooke received no rent for the storehouse. Nor did he receive compensation when his distilling house was filled with hay for several months. A scow he owned was appropriated to move military stores.

In August 1778, an even larger American army descended upon the island, supported by a powerful French fleet. The British withdrew into fortifications built across the southern end of the oblong island, and the Whitehall farm, near the American siege lines, fell into the hands of American forces determined to dislodge the British garrison.[4] Things did not get worse for Cooke, but they did not get any better either. These soldiers were just as opportunistic and hungry as their opponents; they too took crops, livestock and wood in whatever form it could be found. Cooke lost over thirty acres of corn, potatoes, barley and oats; nearly one hundred bushels of onions and beets; hundreds of cabbages; twenty-four tons of hay; some hogs and a large number of fowls; wheels of cheese; a hogshead of molasses; nearly 1,000 fence rails and a similar number of pine boards; and an assortment of tools. The one thing that was better about this army was that it did not stay long. After three weeks, the entire plan to take Rhode Island from the British failed, American troops withdrew, and the British garrison returned to its original posts around the island.

The three week siege brought losses to Cooke not only by American troops, but also by British army soldiers. They drove livestock from Middletown into Newport to prevent the animals from falling into American hands, including three of Cooke’s cows. Army horses were lodged in the stable at his home; there, some partitions were removed to make room for the horses and several tons of hay consumed. For the fortifications that were built to defend the town, wooden planking was needed to make platforms on which to mount cannons. For this purpose, flooring and other planks were removed from Cooke’s distilling houses, as well as from buildings belonging to other inhabitants. Still more fencing became firewood. All of this was in the interest of defending the town, and once again compensation was promised in due time.

After the siege was lifted and the American army departed the island, matters calmed down for a while, but a new enemy soon arrived: cold weather. The war restricted access to the surrounding mainland, the usual peacetime source of firewood. The British army sent troops to eastern Long Island and Shelter Island to cut wood, but the demands of the war limited the numbers that could be employed in this way. The winter of 1778-1779 was a bitterly cold one, and finding enough fuel for both the garrison and the inhabitants became extremely difficult. Sacrifices had to be made. The army began to appropriate anything made of wood that could be spared. A wharf that Cooke had built using ninety-six cords of pine wood was cut up; he was paid for only seven cords, and that at a short rate. Fencing of all sorts was pulled down, even within the town. The Whitehall house was now home to three British officers, some soldiers were quartered in outbuildings, and army sheep and cattle were put on his land. Over 800 trees on the property were cut down that winter, including some 200 valuable fruit trees; also lost was a nursery of young cherry trees numbering some 2,000.

The garrison and residents survived the winter. Cooke suffered many other losses during the three-year British occupation, some from military expedience and others from plunder. Horses were pressed into service and overworked. The scow that had been appropriated early in the occupation was broken up rather than returned. The most invasive indignity occurred in February 1779 when his house was robbed of several silver dishes and buckles, some clothing and some money. A set of silver knee buckles was discovered in possession of Corporal John Edwards of the 38th Regiment, who was reduced in rank as punishment,[5] but there is no evidence that anything else was recovered and Cooke had “all the Reason in ye World to Suspect very foul play in ye affaire.”

Things finally changed in October 1779 when the changing focus of the war led the British to evacuate Rhode Island, abandoning the place that Americans had been unable to take from them. Things got better for Silas Cooke. For the first time in three years, Rhode Island was not a war zone. But the American force that came to defend the island used his distilling houses for storage just as the British had done. Hay, oats, barley and straw were seized by the army in exchange for certificates to be paid at an unspecified future date.

In July 1780, another army came to Aquidneck Island, a French one commanded by General Comte de Rochambeau. Like the British, the French valued Newport’s commodious harbor for their naval forces. The army of some 6,000 troops encamped on the island and recovered from the rigors of their sea voyage. Being new to the area, they were somewhat less opportunistic than the Americans, British and Germans before them. But Silas Cooke nonetheless suffered losses. The French took over his distilling houses and his storehouse, and an officer was quartered in his home. He was given certificates in lieu of rent. For the first time since 1776, though, he claimed no losses by troops.

It is important to recognize that a large portion of Silas Cooke’s losses were caused not by wanton depredations on the part of soldiers, but by the operational demands of a large army stationed on Aquidneck Island. Whichever army happened to be in town made use of his resources, usually paying with promissory notes rather than money. A skilled businessman, Cooke detailed his losses in a series of memoranda. After the war ended he began the process of making claims for the ravages the war had wrought. Needless to say, he had no avenue of redress from the British government. In 1788 he submitted claims to the Rhode Island government, meticulously documenting the losses he’d suffered in property, the rent that he was owed, and the interest that had accrued.

There were many claims like Cooke’s, and the government had limited funds with which to settle them. The process took time. In 1790 Cooke sold off his Newport house, storehouse, distilling house, and the land they were on. He died in South Kingstown two years later. Finally in 1795 his estate was paid its due portion of the money available for settlements, a sum amounting to only a fraction of his losses.

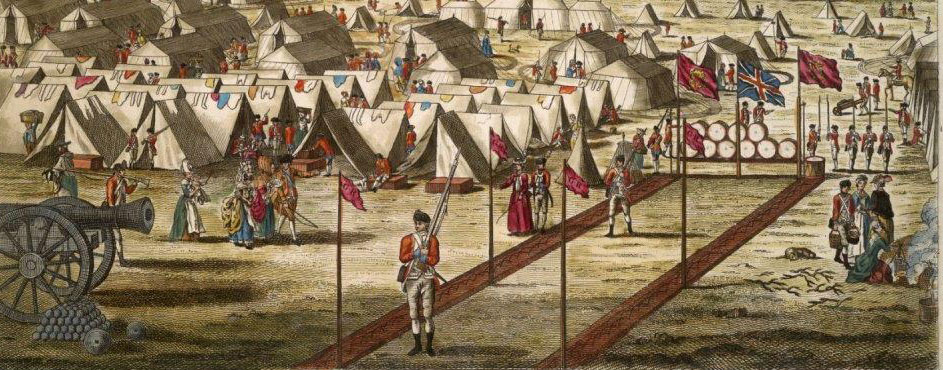

[1] Memoranda of Silas Cooke, as transcribed in Susan Stanton Brayton, “Silas Cooke – A Victim of the Revolution,” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, vol. 31 (1938), pp. 110-116. Information in this article comes from this source unless otherwise cited. [2] For insight into British operations in Rhode Island, see Don N. Hagist, General Orders, Rhode Island (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2001). [3] Cooke’s memoranda give the sergeant’s name as “Roberson”; Jonathan Robertson is the only British sergeant with a name close to this serving in Rhode Island in 1777. Muster rolls, 43rd Regiment of Foot, WO 12/5562/1, British National Archives. [4] For a detailed discussion of the 1778 campaign in Rhode Island, see Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2011). [5] Muster rolls, 38th Regiment of Foot, WO 12/5172. Cooke’s memoranda give Edwards’s name and mention a court martial, and the muster rolls show that he was reduced from corporal to private soldier at this time. For more on John Edwards, go to my blog posting on him at http://redcoat76.blogspot.com/2015/02/john-edwards-38th-regiment-has-knee.html(Banner image: A typical British army regimental encampment (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library ))