From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution, by Robert Geake (Westholme, 2016)

Author Robert A. Geake, an established author of early Rhode Island history and a smallstatebighistory.com contributor making his first foray into the Revolutionary War, writes of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Army, one of the most fascinating regiments of the war—and in all of U.S. military history. After serving honorably in many of the war’s key engagements in the mid-Atlantic region, in February 1778, at the request of Rhode Island Brigadier General James A. Varnum of East Greenwich, the regiment was reestablished as primarily a segregated unit. Slaves were invited to enlist, and if they did, they would become free, and their owners would be paid by the state. Noncommissioned officers and officers would remain white. Interestingly, George Washington, himself one of the country’s largest slaveholders, indirectly approved the proposal by personally forwarding the written proposal to the Rhode Island legislature. Slaves and other men of color, including from the Narragansett tribe, joined the unit and began their training. The former slaves would fight not only for the freedom of their country, but for their own freedom as well.

My own research revealed an incomplete list of enlistments showing that eight of thirty-three of the former slaves, or about 25 percent, had been born in Africa. Thus, they had been taken against their will as slaves, forced onto slave ships and survived the infamous Middle Passage. Now they were fighting in a historic contest of former American colonies trying to gain their independence from the British Crown and forming a new government based on the seeds of democracy and individual freedom.

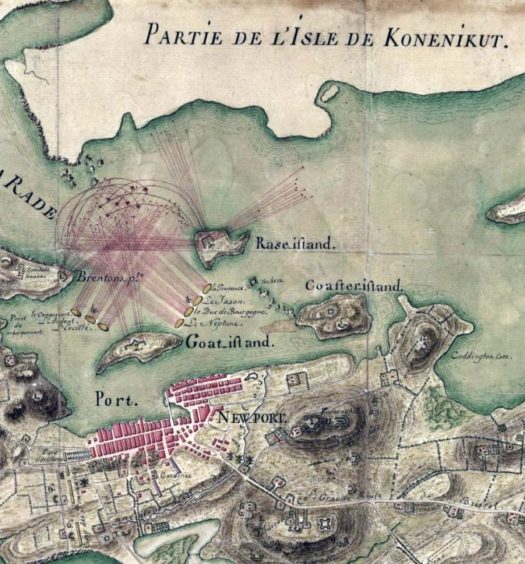

Geake’s book is not a purely military history, but all of the main engagements are covered. The “Black Regiment,” as it became known, came under fire for the first time at the Battle of Rhode Island. Placed at the tip of the American defensive line closest to charging Hessians and Loyalist regiments, the soldiers played a key role in repelling the attackers three times. It was an auspicious start.

On May 14, 1781, in Westchester County, New York, at Pines Bridge on the Croton River, the regiment’s commander, Colonel Christopher Greene of Warwick, Rhode Island (a distant cousin of Major General Nathanael Greene), and a small party of his men, were surprised by a superior Loyalist force under Colonel James DeLancey. Geake concludes that the men of the 1st Rhode Island fought valiantly, refusing to surrender, but most were killed, including Greene.

Later joined with the Rhode Island 2nd Regiment of Continentals and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jeremiah Olney of Providence, the newly-established regiment became the first integrated battalion in the nation’s history. Black troops from the regiment participated in the glorious assault on Redoubt Number Ten at the siege of Yorktown. In winter in early 1783, black and other soldiers of color set out across frozen Lake Oneida on an overnight march in an ill-fated attempt to capture the British post at Oswego. Forced to turn back, many of the soldiers suffered from frostbite, with a number of them disabled for life.

The strongest part of Geake’s book, and most original contribution, is his following up on the post-war lives of the soldiers as they tried to build their lives as freemen. The former slaves were not given any land to farm or other assistance. Many had to take temporary manual labor jobs to survive.

Geake notes that General Varnum desired a stronger federal government, so that it could pay for the salaries owed to Continental army veterans and care for them as needed. But his vision failed and Congress would not pass laws for a federal pension for indigent veterans until 1818 or for all veterans until 1832. In addition, Rhode Island’s legislature also declined to pass laws to assist returning soldiers, despite the former slaves having no houses or property of their own, and with some of them suffering from wartime disabilities. The General Assembly’s solution was to place the care for these veterans in the hands of the town from which they enlisted, declaring that “it shall be the duty of the town council of the town where such Indian, negro, or mulatto, who was heretofore a slave, and enlisted in the Continental battalions as aforesaid…to direct the overseers of the poor of such town to take care and provide for such….” This traditional approach to poor relief was not an efficient solution to help returning veterans who had been former slaves.

In the post-war period, Geake found, numerous veterans, dependents, widows, and children of Revolutionary War veterans were also “warned out” of their local communities. This was the case, for example, with Nancy Hull and Sally Saltonstall, the partner and daughter of Briton Saltonstall, a veteran of the 1st Rhode Island who suffered frostbite at Oswego. With Briton unable to support his family, Nancy and Sally were forcibly removed to New York, the mother’s supposed last lawful place of residence.

Still, into the mid-1830s, black veterans such as Guy Watson of South Kingstown were cheered at July 4 parades and other events at which Revolutionary War veterans were honored. In discussing the legacy of this unique regiment, Geake explains that the story of First Rhode Island was used by abolitionists to oppose slavery in the South. One New Hampshire doctor, in an anti-slavery address in 1842, declared that the former slaves of the First Rhode Island “fought because they would not be slaves. Those whom liberty has cost nothing do not know how to prize it.”

Geake, with the assistance of Lorén Spears, Executive Director of the Tomaquag Museum, further describes the pride of the Narragansett tribe in about seventy of its men who enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island. They write, “The indigenous Rhode Island soldiers’ contribution to the Revolutionary War was remembered well into the twentieth century through oral history, and occasionally in print.” They further explain that after some Narragansetts intermarried with blacks, their children were labelled by white officials as “colored,” with the result of intentionally or unintentionally helping to erase the identity of indigenous people and their communities.

Readers who are interested in a unique history, and a slim one (at 130 pages of main text), are encouraged to read this book.