We live in a day wherein Liberty & freedom is the subject of many millions’ Concern; and the important Struggle hath already caused great Effusion of Blood; men seem to manifest the most sanguine resolution not to Let their natural rights go without their Lives go with them; a resolution, one would think Every one that has the Least Love to his country, or future posterity, would fully confide in, yet while we are so zealous to maintain, and foster our own invaded rights, it cannot be tho’t impertinent for us Candidly to reflect on our own conduct, and I doubt not But that we shall find that subsisting in the midst of us, that may with propriety be styled Oppression, nay, much greater oppression, than that which Englishmen seem so much to spurn at. I mean an oppression which they, themselves, impose upon others (Minister Lemuel Haynes, “Liberty Further Extended,” 1776).

In the 18th century, there were three revolutions in North America. There was rebellion against imperial British rule led by American colonists, a social revolution against African slavery and the slave trade led by a mixture of whites and Black abolitionists, and an insurrection against the slave system led by enslaved men and women in the North and the South who fled bondage to seek freedom behind military lines.

Americans, both enslaved and free, were inspired by the ideological fervor of Revolutionary rhetoric and began, for the first time in modern history, to question the place of the institution of human bondage within their society and to think of ways to dismantle it. As historian Sean Wilentz has noted, the Revolution represented a “pioneering American antislavery” moment – leading to the “most advanced and effective antislavery upsurge of its kind in the Atlantic world before 1787.”[1] From the middle of the 1760s to the outbreak of fighting in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, a flood of antislavery petitions, sermons, and pamphlets questioned a practice that had been part of life in the North American colonies (in both the North and the South) for over 150 years.

What emerged in the Revolutionary era was a moral sense that the slave system was constructed by human actions and, therefore, could be corrected by practical human action. As historian Christopher Brown notes in his landmark work, Moral Capitalism, if the colonists had “presented their case in more parochial and exclusively constitutional terms, if they had argued only for the customary rights and liberties of Englishmen, perhaps, as before, few settlers in British North America, would have thought about the rights of Africans.”[2] Those “who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves, should be willing to extend personal liberty to others,” declared a Rhode Island statute barring the importation of African slaves.[3]

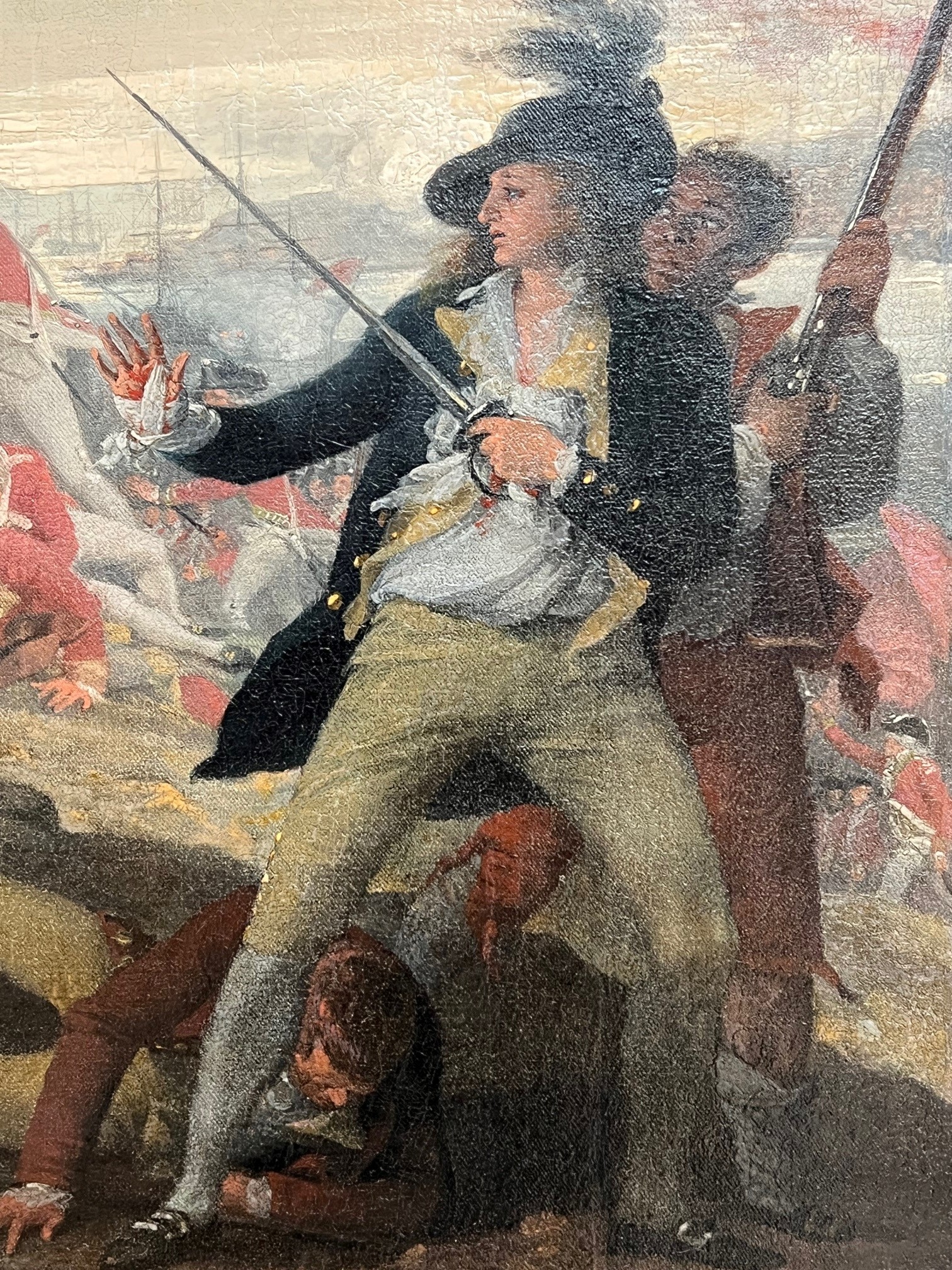

An Black soldier is shown fighting on the side of the patriots in the painting, “The Battle of Bunker’s Hill,” by John Trumbull (Yale University Art Gallery).

The widespread notion for much of the 16th and 17th centuries that African slaves were “generally treated very well, and many of them much better than they deserve,” for the first time began to be challenged. The “partaker was as bad as the thief,” noted Newport minister Samuel Hopkins in 1776.[4] At time of Hopkins’ comments, however, nearly half of Newport’s richest residents had an interest in the slave trade.[5]

These stories are not often told together, but in his brilliant and engaging new book, American Inheritance: Liberty and Slavery in the Birth of the Nation, 1765-1795, historian and legal scholar Edward Larson demonstrates the interconnection through a careful mining of the sources and a deep understanding of the abundant scholarship on the topic. The publication of Larson’s work will hopefully inspire Rhode Island educators to bring this rich story into the classroom and to think of ways to engage with the rich material available from the educational team at the Rhode Island Historical Society.

As Larson notes, the discussion of liberty and slavery in the Revolution is a “partisan minefield” thanks to the publication of the New York Times 1619 Project several years ago. However, this should not deter serious students of history from examining the sources and grappling with the complexity and ironies Larson brings to the forefront.[6] Moreover, American Inheritance should inspire historians to produce a new history of the Revolutionary era—including in Rhode Island. It is time for an update to David Lovejoy’s classic 1958 work, Rhode Island Politics And The American Revolution 1760-1776.

In American Inheritance, Larson pays particular attention to the distance between professed values of liberty and the harsh reality of an economic system structured on slave labor. Take, for example, the comments made in 1775 by the British legal scholar Josiah Tucker, the author of a series of pro-independence pamphlets on the Revolution. Permit me to “therefore ask why are not the poor Negroes and the poor Indians, entitled to the like Rights and Benefits?” asked Tucker. And how has it come to “pass, that these immutable Laws of Nature become so very mutable, and so very insignificant” when the status of slaves is being discussed?[7] As Larson notes, the Revolutionary era left an “enduring legacy: a distinctively American heritage of liberty and slavery – two intertwined strands of national DNA.” The Revolution and the nation that emerged “became less about liberty or slavery than about liberty and slavery.”

Stephen Hopkins, many times governor of the colony of Rhode Island and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Prior to and during the American Revolution, he pushed for abolitionist legislation from the General Assembly and emancipated most of the enslaved persons he held, with one exception (Brown University Portrait Collection).

American Inheritance opens with several engaging chapters on the rhetoric of slavery and bondage utilized by the Patriots to describe their situation under British imperial rule.[8] White Patriots repeatedly warned of becoming “slaves” to the British Crown or Parliament Larson discusses the 1765 pamphlet authored by long-time Rhode Island governor, merchant and slave-ship owner Stephen Hopkins, who declared that liberty was “the greatest blessing that men enjoy, and slavery the heaviest curse that human nature is capable of.” Hopkins served as a delegate from Rhode Island in the Continental Congress and in July 1776, signed the Declaration of Independence.

Hopkins declared that the colonists were “in the miserable condition of slaves.” It was indeed the “heaviest curse human nature is capable of.”[9] At the time, Hopkins owned several slaves. His close friends, the Brown brothers of Providence, forwarded a copy of the pamphlet to Hopkins’s younger brother Esek, who was then off the coast of Africa aboard the slave ship Sally. The voyage of the Sally would be one of the deadliest in North American history; of 136 African captives acquired, 109 died, most from disease, but some by being killed in an unsuccessful insurrection or by suicide.[10]

In 1764-65, Rhode Island merchants went to great lengths to avoid paying the newly enacted Sugar Act, especially on molasses brought in from the Dutch colony of Surinam.[11] Molasses was turned into rum in major Rhode Island port cities, especially Newport and Bristol, some of which would then be used as a principal trading commodity in the slave trade on the African coast. Reflecting on the origins of the American Revolution, John Adams noted that “I know not why We Should blush to confess that Molasses was an essential Ingredient in American independence.”[12]

Spurred by the ideological fervor of the Revolution and the clarion calls for liberty, by the time shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775, Hopkins had become an opponent of both slavery and the slave trade.[13] Hopkins, a slave owner for many years, freed his slaves, save for one, by 1773.[14]

Larson uses the writings of Reverend Samuel Hopkins (no relation to Stephen) to highlight the emergent antislavery ideology of the period.[15] Samuel Hopkins served as the pastor of the First Congregationalist Church in Newport. In the spring of 1776, prior to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, Hopkins published, A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of the Africans, Showing It to be the Duty and Interest of the American Colonies to Emancipate All the African Slaves. Hopkins dedicated the pamphlet to the members of the Second Continental Congress, then meeting in Philadelphia, and urged the delegates to abolish slavery in British North America.

Hopkins’ abolitionist agenda stemmed directly from the fervor of the Revolution. Hopkins saw the divine hand of God in the war, with the “distresses” the American colonists felt stemming from “the sin of holding our blacks in slavery.”[16] In the autumn of 1776, he told his congregation to “exert” themselves for “universal Liberty.”[17] Invoking the language of equality in Jefferson’s Declaration published a few months before, Hopkins noted that it was “self Evident, as the Honorable Continental Congress” observed: “that all men are created equal, and alike endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, as Life, Liberty the pursuit of happiness.”[18]

Hopkins’ hatred of slavery stemmed directly from his arrival in Newport, a major hub in the Atlantic slave trade, in 1769. On the streets of the coastal community, Hopkins would have encountered slaves nearly everywhere he went.[19] Hopkins told Providence Quaker Moses Brown that Newport “is the most guilty respecting the slave trade, of any on the continent.” The town, he said, was built “by the blood of the poor Africans; and that the only way to escape the effects of divine displeasure, is to be sensible of the sin, repent, and reform.”[20] As historian Jonathan Sassi has noted, Hopkins’ antislavery ideology was also influenced by his relationship with congregant Sarah Osborn and the writings of the Philadelphia Quaker Anthony Benezet, likely given to Hopkins by friends of Moses Brown.[21]

Reflecting on his move to Newport from the town of Great Barrington in the far western region of Massachusetts, Hopkins noted that his “attention was soon turned to the slave trade, which had been long carried on here, and was still continued. It appeared to me wholly unjustifiable and exceedingly inhumane and cruel.” In a January 1789 letter to the British abolitionist Granville Sharp, he said he was “obliged” to “condemn it in public and preach against it.”[22]

As Larson notes, Reverend Lemuel Haynes, a mixed-race disciple of Hopkins, wrote a fiery address that serves as a precursor to the Black abolitionist David Walker’s 1829 Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. “But while we are Engaged in the important struggle, it cannot Be tho’t impertinent for us to turn one Eye into our own Breast, for a little moment, and See, whether thro’ some inadvertency, or a self-contracted Spirit, we Do not find the monster Lurking in our own Bosom,” wrote Haynes.[23]

Of special interest to students of Rhode Island history will be Larson’s discussion of the First Rhode Island regiment – an all-Black military unit. As Larson notes, there was intense debate during the Revolution over who should be allowed to defend American liberties. As states struggled to meet enlistment quotas set by the Continental Congress, many responded by opening military service to men of color. In February 1778, the General Assembly, at the behest of officers in the two Rhode Island battalions encamped at Valley Forge in Pennsylvania, authorized the organization of a battalion of slaves.[24] It is important to point out that a few African American males were engaged in military service prior to 1778, mainly serving as substitutes for their masters who had been drafted for county militia service by the General Assembly.

One fascinating area of study not covered by Larson has recently been brought to light by historian Christian McBurney. When the war began in the spring of 1775, the British saw American slaves as potential military allies. They offered liberty to those willing to flee plantations. This rebellion led by African Americans was in addition to white colonials’ rejection of British rule and constituted the largest slave revolt in American history prior to the Civil War period. The British occupation of Newport in December 1776 created opportunities for enslaved Rhode Islanders on Aquidneck Island to flee from their masters.[25] As McBurney points out, some slaves and other persons of color fled a life of bondage to work for the British army or navy. As McBurney also notes, the “Book of Negroes,” a list kept by the British of over 3,000 Blacks who departed New York City on British ships in 1783, includes the names of 31 Blacks from Rhode Island.[26] Larson’s account will help students contextualize the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778 by seeing how the rhetoric of freedom played out with the specter of Black troops fighting for the Patriots on one side and the promises offered by the British to Black slaves to aid the Red Coats on the other.[27]

In the second half of the narrative, Larson covers the various methods states utilized in the post-Revolutionary era as they dismantled slave systems, along with the adoption and ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Rhode Island’s 1784 gradual emancipation bill is not discussed in detail by Larson so students should turn to Joanne Pope Melish’s informed discussion in her important work, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (1998).[28] The General Assembly invoked the Declaration of Independence, declaring that “all men are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and the holding mankind in a state of slavery, as private property, which has gradually obtained by unrestrained custom and the permission of the laws, is repugnant to this principle.” It freed all children born after March 1, 1784, and relieved masters of the expense of raising them by binding them out, as with paupers, till the ages of 21 for women and 18 for men.[29] Though the discussion is brief, Larson does highlight the strong antislavery objections to the 1787 Constitution discussed in the protracted debate in Rhode Island over ratification of the U.S. Constitution.[30]

Larson ends his brilliant work with a discussion of the correspondence between the Black scientist Benjamin Banneker and Thomas Jefferson. Banneker encouraged Jefferson to accept “the indispensable duty of those who maintain for themselves the rights of human nature,” by ending the “State of tyrannical thraldom, and inhuman captivity, to which too many of my brethren are doomed.” Citing the “Self-Evident” truth “that all men are created equal,” Banneker challenged Jefferson and others “to wean” themselves “from those narrow prejudices which you have imbibed with respect to” African Americans.[31] Fifty years later, Black leaders used similar language to challenge both the sitting Rhode Island government and a revolutionary group of suffrage leaders to afford them the full measures of liberty mentioned in Jefferson’s Declaration.[32]

There is no doubt that slavery grew in the new United States in the wake of the Revolution. Due in large part to the construction of the 1787 Constitution, slaveholders possessed considerable influence in the corridors of power in Washington. However, as Edward Larson makes clear, the Revolution served to hasten the eventual destruction of slavery in North America by the middle of the 19th century. This is a story worth understanding and certainly worth teaching to the next generation of Americans.[33]

[1] Sean Wilentz, “The Paradox of the American Revolution,” The New York Review of Books (January 13, 2022). See also Wilentz, “American Slavery and the ‘Relentless Unforeseen’,” The New York Review of Books, November 19, 2019. Wilentz’s review essays should prompt this current generation to read David Brion Davis’s classic work, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (1975), along with Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery American Freedom (1975). [2] Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capitalism: Foundations of British Abolitionism (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 105. [3] This 1775 document has been digitized by the Rhode Island State Archives. See https://catalog.sos.ri.gov/repositories/2/digital_object_components/55. [4] Quotes taken from Samuel Hopkins’s 1776 “dialogue” on slavery. See https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N15010.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext. [5] See Paul Davis, “Plantations in the North,” Providence Journal series “Unrighteous Traffick”: https://stories.usatodaynetwork.com/slaveryinrhodeisland/plantations-in-the-north-the-narragansett-planters/site/providencejournal.com/ For more on slavery in Rhode Island see Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York University Press, 2018). [6] See Erik J. Chaput’s critique of the 1619 Project in the Providence Journal from January 2020:https://www.providencejournal.com/story/opinion/2020/01/22/my-turn-eric-j-chaput-newspaper-pushes-faulty-us-history/1849849007/ See also historian Matt Karp’s lengthy critique in Harper’s Weekly, “History as End”: https://harpers.org/archive/2021/07/history-as-end-politics-of-the-past-matthew-karp/. [7] For a sketch of Tucker’s life and career see Salim Rashid, “‘He Startled… As If He Saw a Spectre’: Tucker’s Proposal for American Independence,” Journal of the History of Ideas 43:3 (1982), 439–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2709432. The quotes come from page 5 of Josiah Tucker, Tract V, The Respective Pleas and Arguments of the Mother Country, and of the Colonies (London, 1775). [8] See Peter A. Dorsey, “To ‘Corroborate Our Own Claims’: Public Positioning and the Slavery Metaphor in Revolutionary America,” American Quarterly 55:3 (2003), 353–86 (accessed at http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041981). See also Gordon S. Wood, The American Revolution: Writings from the Pamphlet Debate 1764-1776, 2 vols. (Library Company, 2015). [9] Hopkins pamphlet can be accessed at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N07846.0001.001/1:2?rgn=div1;view=fulltext. [10] See https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/sally/narr_communicating.html. For more on the voyage of the ship Sally see Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, The Slave Trade, and the American Revolution (Simon and Schuster, 2006), 75-101. [11] For teaching document see the America in Class page devoted to the Revolution: https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/crisis/text2/sugaractresponse1764.pdf. [12] For teaching document see the America in Class page devoted to the Revolution: https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/crisis/text2/sugaractresponse1764.pdf. [13] Christian M. McBurney, “The American Revolution Sees the First Efforts to Limit the African Slave Trade,” in Don N. Hagist, ed., Journal of the American Revolution Annual Volume 2021 (Westholme, 2021). [14] See Christian M. McBurney’s detailed essay surveying the pros and cons of removing the Esek Hopkins statue in Providence: https://smallstatebighistory.com/evaluating-whether-to-remove-a-statue-or-other-honorific-the-case-of-esek-hopkins. [15] David S. Lovejoy, “Samuel Hopkins: Religion, Slavery, and the Revolution,” The New England Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1967): 227–43 (accessed at https://doi.org/10.2307/363769). See also Cherry Fletcher Bamberg,“ Bristol Yamma and John Quamine in Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History 73:1 (Winter/Spring 2015): 5-31. [16] Quotes taken from Samuel Hopkins’ 1776 “Dialogue” on slavery (accessed at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N15010.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext). [17] See Jonathan D. Sassi, “‘This whole country have their hands full of Blood this day’: Transcription and Introduction of an Antislavery Sermon Manuscript Attributed to the Reverend Samuel Hopkins,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (Spring, 2004), 39 (accessed at https://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44539532.pdf (April 9, 2023). See also Stanley K. Schultz, “The Making of a Reformer: The Reverend Samuel Hopkins as an Eighteenth-Century Abolitionist,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115:5 (1971), 350–65 (accessed at http://www.jstor.org/stable/985768). [18] Sassi, “This whole country,” 71. [19] For more on Newport in the Revolutionary era see historian Elaine Forman Crane’s often overlooked work, A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (Fordham University Press, 1992). See also journalist Paul Davis’s important six-part series in the Providence Journal on slavery in Rhode Island, which can be found at https://stories.usatodaynetwork.com/slaveryinrhodeisland/. See also the digital textbook produced by the Rhode Island Historical Society and the digital service team at Providence College at https://library.providence.edu/encompass/ [20] Quoted in Schultz, “The making of a reformer,” 355. [21] Sassi, “This whole country,” 49, 55. See also Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, “The Spiritual Pilgrimage of Sarah Osborn (1714-1796),” Church History 61, no. 4 (1992), 408–21 (accessed at https://doi.org/10.2307/3167794). See also Woody Holton, Liberty is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2022), 50-51, 79-80, 112 and Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capitalism, 350. [22] See Edward Amasa Park, Memoir of the Life and Character of Samuel Hopkins (Boston, 1854), 140. [23] Haynes’ fiery sermon serves a wonderful teaching tool and can be found on the Gilder Lehrman Foundation website at http://storage.gilderlehrman.org/dec250/Lemuel%20Haynes,%20Liberty%20Further%20Extended%20(1776).pdf. See also Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 209), 63-65. [24] John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 206-207. [25] Christian M. McBurney, “Freedom for African Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes’,” Newport History 82:2 (2017), 1. [26] The “Book of Negroes” can be searched at https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/loyalists/book-of-negroes/Pages/introduction.aspx#c. [27] See also Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Westholme, 2011). [28] See also Samuel Hopkins and John Saillant, “‘Some Thoughts on the Subject of Freeing the Negro Slaves in the Colony of Connecticut, Humbly Offered to the Consideration of All Friends to Liberty & Justice,’ by Levi Hart,” The New England Quarterly 75, no. 1 (2002): 107–28 (accessed at https://doi.org/10.2307/1559883). [29] A digitized version can be found on the website for the Rhode Island State Archives at https://catalog.sos.ri.gov/repositories/2/digital_object_components/73. [30] See Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone’s essay on ratification at http://smallstatebighistory.com/providences-merchants-influence-state-ratify-u-s-constitution-1790/. Thanks to the efforts of historian Patrick T. Conley, there are now four volumes of material relating to Rhode Island and the ratification debate (see https://csac.history.wisc.edu/publications-2/dhrc/). See also Patrick T. Conley, First in War, Last in Peace: Rhode Island and the Constitution (Rhode Island Publications Society, 1987). [31] See the full letter at https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0049. [32] See Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone, “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race In Antebellum Rhode Island,” Common Place 10.2 (January, 2010) at http://commonplace.online/article/strange-bedfellows/. [33] Teachers should also engage with the wonderful collection of essays in John Craig Hammond and Matthew Mason eds., The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New American Nation (University of Virginia Press, 2011). See especially the essay by Robert G. Parkinson and his discussion of the impact of the Somerset case (1772), which Larson covers in detail.