[This is the first in a series of four articles honoring the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Point Judith. This first article is based mostly on part of a chapter written by the author in the book World War II Rhode Island (History Press, 2017)]

Rhode Island’s formidable defenses that were constructed within Narragansett Bay were never tested during World War II. Still, two notable military incidents occurred off its shores as the war against Germany just was coming to an end.

First, the last sinking of a U.S.-flagged merchant vessel by a German U-boat happened on May 5, 1945, less than three miles southeast of Point Judith. It was also the ship sunk closest to the American mainland by a foreign power since the War of 1812. Twelve of the forty-six crewman of the coal-carrying collier that was the U-boat’s victim, named Black Point, were killed or drowned.

A day later the same U-boat that sank the collier itself was destroyed, again within sight of Point Judith. It was the last (probably second-to-last) sinking of a German submarine by U.S. forces in World War II. All fifty-five submariners aboard U-853 were entombed in their submerged vessel at the bottom of Rhode Island Sound.

May 5 and May 6 of this year are the 75th anniversaries of both events.

Concern about German U-boats peaked early in the war, when what Germans called “wolf packs” of their submarines prowled the exposed and virtually unprotected East Coast, sinking hundreds of Allied ships. In 1942, nine merchant vessels were sunk by U-boats off the New England coast alone. U-boats were sinking allied ships faster than the allies could build them.

Rhode Island’s expansive U.S. Navy facilities had as one of their missions searching for and destroying U-boats. Destroyers and PT boats operated out of Newport and Melville, while submarine spotting and killing aircraft flew from the Naval Air Station at Quonset Point. Few U-boats ventured close to Narragansett Bay given these impressive forces.

Finally, by late spring 1943, increasingly effective submarine hunting by U.S. Navy ships and airplanes, with the assistance of radar, turned the tide in what was called the Battle of the Atlantic. The heavy toll on German submarines was typified by the sinking of U-550 by destroyers off of Nantucket on April 16, 1944. One of U-550’s survivors, Gunter Herd, was brought to Newport Naval Hospital, but died June 5 later of his injuries. He is buried in the Island Cemetery Annex in Newport.

Gravestone for Gunther Heder, a German submariner who died at Newport Hospital on June 5, 1944, at Island Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island. Heder escaped from the sinking German U-boat 550 off Nantucket but died shortly thereafter. He apparently survived long enough to provide the details of his life for his gravestone (Christian McBurney)

By 1944, the threat of attack from enemy ships and submarines was deemed to be so slight that several of Narragansett Bay’s coastal forts had been deactivated. In early May 1945, within days of the end of the war in Europe, that situation changed when U-853 entered Rhode Island Sound.

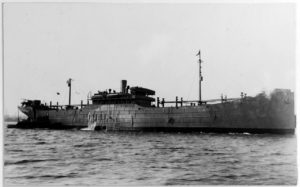

U-853, commissioned June 25, 1943, was 252 feet long and with a beam of 22 feet and 8 inches. The German submarine was equipped with four torpedo tubes in the bow and two in the stern, and on its deck carried a 4.1 inch gun and two anti-aircraft guns. On two previous war patrols, one under the command of Helmut Sommer and the other under command of Guenther Kuhnke, it sunk two ships amounting to 5,783 tons.

U-853 had a reputation for escaping from perilous attacks. On its second war patrol in May 1944, after sighting and chasing the massive Queen Mary, which had been converted into a troop carrier, U-853 was attacked while riding on the surface by three British Swordfish aircraft but escaped unharmed.

Then, on June 15, 1944, U.S. Navy escort aircraft carrier Croatan (which would visit Quonset in February 1945) and several destroyers caught U-853 steaming on the surface, but the submarine dived and escaped again. Two days later, two aircraft intercepted the submarine, again steaming on the surface, killing two submariners and wounding the commander and eleven others. But U-853 was able to submerge before it could be destroyed. Germans nicknamed the U-boat the Tightrope Walker and Croatan’s crew Moby Dick (due to the its elusiveness).

On February 23, 1945, after being repaired and refitted, the German navy command ordered U-853 and its fifty-five man crew on its third war patrol. It would join four other U-boats in a last-ditch effort to attack U.S. coastal shipping, with the hope of improving Germany’s bargaining position should Hitler seek a conditional surrender.

U-853’s new commander, Lieutenant Helmut Frömsdorf, was just twenty-four-years-old. He did have experience, serving as second-in-command on the submarine’s second patrol under Kuhnke. He wrote to his parents in a letter, “I am lucky in these difficult days of my Fatherland to have the honor of commanding this submarine, and it is my duty to accept.” He concluded, “I’m not very good at last words, so goodbye for now, and give my sister my love.”

After departing its base from Stavenger, Norway, U-853’s Atlantic crossing was slow, as Frömsdorf kept his submarine submerged as much as possible to avoid being spotted by Allied aircraft. He was able to keep submerged by using a new device, called a snorkel.

German U-boat U-853 is commissioned on June 25, 1943, prior to its initial voyage (Naval War College Museum)

On April 23, 1945, U-853 torpedoed Eagle Boat 56, a World War I-era patrol boat off of Portland, Maine. A total of fifty-four sailors met their deaths and only thirteen survived. Only in 2001 did the U.S. Navy concede that U-853 was responsible for the attack.

The same day she sunk Eagle Boat 56, U-853 was attacked by a destroyer, USS Selfridge, which dropped nine depth charges on the suspected enemy submarine. Early in the morning of April 25, in the Gulf of Maine, the USS Muskeogen located by sonar what was probably U-853. The Muskeogen fired a full complement of hedgehogs but no results of a hit were seen.

The next day at 3 p.m., a radar operator in a plane whose squadron had taken off from Quonset Point and was flying over the Gulf of Maine, detected a U-boat, probably U-853. “The radar said there was a submarine sitting on top of the water about 40 miles away charging their batteries,” recalled air crewman William Heckendorf. “We homed in on it and saw the oil slick on the water where it had been sitting. We dropped our sonar gear and picked up the sound of a submarine’s engine. We pinpointed the sub and dropped two 500-pound depth charges. About five minutes later the ocean was full of debris and oil.” The submarine’s skipper may have intentionally discharged oil and debris to fool the attackers into thinking that the submarine had been sunk.

It is known that Frömsdorf decided to sail his submarine to Rhode Island Sound. As in the Gulf of Maine, the consequences were tragic.

On May 4, 1945, at 5:30 a.m. eastern time, Germany’s navy chief and newly-anointed President of German (Hitler was dead), Admiral Karl Dönitz, by radio ordered all U-boats to cease hostilities. Lieutenant Frömsdorf did not heed the message.

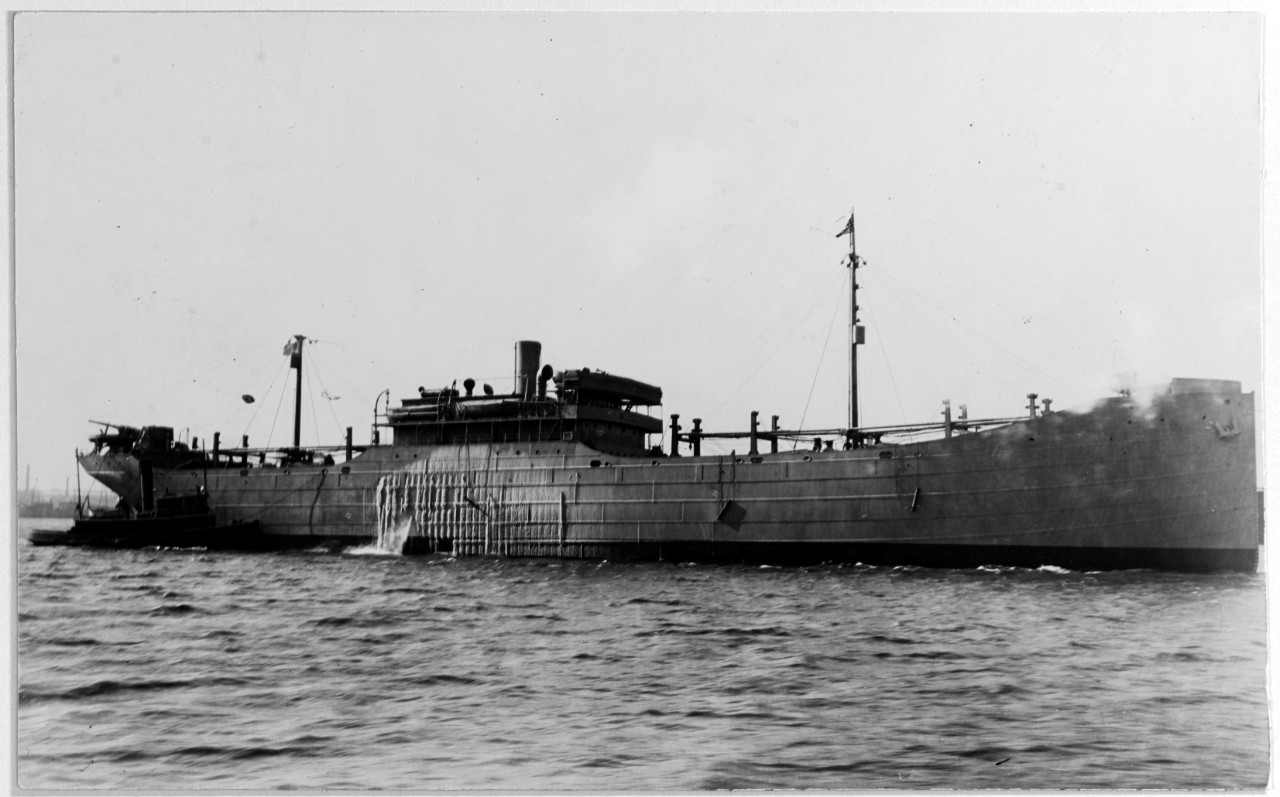

In the late afternoon of May 5, Frömsdorf spotted in his periscope the SS Black Point, a 368-foot, 5,000 ton collier, launched in late 1917, carrying 7,500 tons of coal on a voyage from Newport News, Virginia, to Weymouth, Massachusetts. Black Point in 1918 had made two voyages carrying supplies to the U.S. army in France and after the war had ended had participated in a food relief program, bringing flour and coal to Holland. In May 1942, while operating on the American East Coast in the civilian U.S. merchant fleet, Black Point received a 6-pounder gun in its stern. Navy armed guards were assigned to man the gun and defend the ship, in case of attack.

The U.S. coal collier SS Black Point before her sinking. Note the deck gun in its stern (National Archives)

Black Point was then less than three miles southeast of Point Judith and about seven and one-half miles northeast of Sandy Point on Block Island. The German submarine commander did not spot any enemy warships in his periscope in the East Passage to Narragansett Bay or elsewhere in Rhode Island Sound. Seeing the rough seas and poor visibility, and with overcast skies limiting air operations, the German captain ordered a torpedo to be fired.

In the minutes before the torpedo sped from the submarine, on board Black Point, radioman Raymond Tharl later recalled, “As far as anybody knew, the war was over.” Believing his unescorted ship was in safe waters, its captain Charles E. Prior, did not bother to post lookouts or to zigzag to avoid submarine torpedoes. Most of the crew was eating dinner when Frömsdorf gave the order to fire.

At 5:40 p.m., U-853’s torpedo struck the vulnerable stern of Black Point. A staggering explosion rocked the collier and blew off its 6-pounder, provoking chaos on board. The stricken vessel’s captain, in interviews with the Providence Journal in 1985, said, “I don’t mind telling you that it hit the fan all right. The mainmast went over the port side, and about everything on the bridge that was breakable did break. The vibration and concussion was really something. It blew open both doors of the pilothouse.” He further informed the newspaper in 1945, “the stern of the ship was blown off and sank to the deck level immediately. The men below decks aft didn’t have a chance.”

Captain Prior immediately gave the order to abandon ship and was the last survivor to leave his vessel. Black Point rolled over twenty-five minutes later and went down stern first, carrying the bodies of eleven crewmen and a Navy petty officer, Lonnie Lloyd, in charge of a four-man armed guard, with it. “It stood straight up and the last thing I saw was the belly of it,” merchant seaman Howard Locke recalled, who saw it from a life raft crammed with sixteen other surviving crewmen. The stricken vessel settled on the ocean floor 100-feet below.

Seven men took to boat number 1, but boat number 2 swamped in the water, its occupants had to be rescued by the other boat. Blown clear of the ship, one of the armed Navy guards, Stephen Svetz, struggled in the sea, experiencing considerable difficulty. Seeing his shipmate in distress, another armed Navy guard, Henry T. Berryhill, climbed over the heaving debris in the water, grabbed Svetz by the shoulders, and dragged him into the boat, thereby saving his life.

Thirty-four crew members were rescued. Air-sea rescue boats sent from Quonset Point picked up fifteen survivors, landing them at Newport. Coast Guard boats took in the remaining nineteen survivors, taking them to the nearby Point Judith Coast Guard Station. Fifteen of the thirty-four survivors were taken to the U.S. Naval Hospital at Newport.

The most perplexing question regarding the sinking of Black Point is whether Frömsdorf never received the radio message from Admiral Dönitz ordering all U-boats to cease hostilities, or whether he received it and ignored it. The answer will never be known with certainty, but the best evidence is that he never received Dönitz’s message. Most likely U-853’s radio equipment became broken shortly after the submarine’s departure from Europe or Frömsdorf stayed submerged as much as possible, during which time he could not receive messages from Germany, and his radio equipment was then damaged by the attacks on his submarine in the Gulf of Maine.

Strong support for the position that Frömsdorf’s radio equipment did not work was revealed in post-war correspondence between the submarine captain’s sister, Helga Deisting, and his flotilla commander in Germany, Guenther Kuhnke. According to Kuhnke, after U-853’s departure from Norway, he never heard from Frömsdorf again. Contrary to normal operating procedures, U-853 failed to radio back to headquarters. Kunhnke thought that this approach kept the crew alive into May. The other four submarines all reported in regularly, but they were sunk by early April. It appears their radio messages had been intercepted by U.S. intelligence forces, leading to their sinkings. This is a topic that merits more study by historians of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Frömsdorf’s decision to steer U-853 into Rhode Island Sound, so close to Newport and Quonset Point, could be considered evidence that the submarine commander had a desire to end his submarine’s patrol in a burst of supposed glory, but it is not persuasive evidence by itself. According to Frömsdorf’s sister, the captain was neither a fanatic nor a member of the Nazi party. There is little reason to suspect that he was eager to spill more American blood and risk that of his crew’s in a defunct cause.

Still, before the departure of U-853, Frömsdorf’s former commander had advised the young captain not to risk unnecessarily the lives of his men. By going so close to the powerful Navy base at Newport and Naval air station at Quonset Point, and in shallow waters close to the U.S. coastline, Frömsdorf was doing what his former commander had warned him to avoid. Frömsdorf and his crew would soon suffer the consequences.

Next in the four-part series: was an opportunity to avoid the sinking of Black Point mishandled?

[Banner image: The U.S. coal collier SS Black Point prior to her sinking. (National Archives)]

Bibliography:

This article is based mostly on part of a chapter written by the author in the book World War Rhode Island (History Press, 2017) by Christian McBurney, Brian L. Wallin, Patrick T. Conley, John W. Kennedy, and Maureen A. Taylor.

Books

Downie, Robert. Block Island—The Land. Block Island, RI: Book Nook Press, 1999.

Offley, Ed. The Burning Shore, How Hitler’s U-Boats Brought War to America. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Puelo, Stephen. The True World War II Story of the USS Eagle 56. Guildford, CT: Lyons Press, 2005) (also quoting Frömsdorf’s letter to his parents).

Schroder, Walter K. Defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II. Providence: Rhode Island Publications Society, 1980.

Periodicals

Arnold, David. “The Final Hours of the U-853.” The Boston Globe Magazine, May 5, 1985 (summarizing letters from Guenther Kuhnke and Helga Deisting).

Arsenault, Mark. “The Night World War II Came to R.I.” Providence Journal, May 6, 1998.

Boston Globe. “39 Saved, One Missing after Sub Scores Three Hits Close Off L.I. Shore,” January 15, 1942.

Carbone, Gerald M. “’They Were All Somebody’s Sons.’” Providence Journal, May 6, 1995.

Lynch, Adam. “Kill and Be Killed? The U-853 Mystery.” Naval History Magazine 22, no. 3 (June 2008).

Other

Cressman, Robert J. Ship Histories: Fairmont (Id. No. 2429) (March 20, 2016). http://www.history.navy.mil (Black Point was originally named Fairmont)

DiCarpio, Ralph. “The Battle of Point Judith.” Destroyer Escort Sailors Association. http://www.desausa.org/Stories/battle_of_point_judith_2.htm.

“German submarine U-853.” Online Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_submarine_U-853

World Public Library. “German Submarine U-853.” www.worldlibrary.org/articles/German_submarine_U-853