In 1912 a third edition of Jacob Frieze’s book, A Concise History of Efforts to Obtain an Extension of Suffrage in Rhode Island; from 1811 to 1842, was reprinted by Freize’s son, Lyman. Frieze’s book was first printed in 1842 immediately following the tumultuous Dorr Rebellion. The book’s popularity caused a second edition to be printed soon after the first edition. The question must be asked: why after seventy years was a third edition needed?

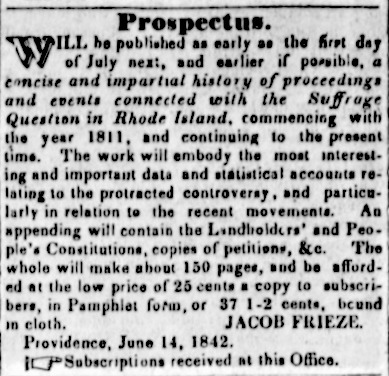

Prospectus for Frieze’s book ,appeared in the newspaper The Northern Star and Farmer’s and Mechanics’ Advocate on July 9, 1842.

Jacob Frieze (1786 – 1880) was a journalist and Universalist minister. His book is one of the more detailed accounts of the Dorr Rebellion printed at the time.[1] Frieze favored suffrage extension and had been active in the suffrage movement, first as a supporter of the Constitutional Party of the mid-1830s and then as a member of the Rhode Island Suffrage Association in 1840. He left the Suffrage Association in July 1841 when he felt that members of the Democratic Party had “foisted themselves” on the Association.

In his book, Frieze criticized the actions of both sides of the political spectrum. Of the conservative politicians who resisted suffrage extension in 1834, eight years before the rebellion, he questioned their sincerity and that of the state legislature when it moved to hold a constitutional convention. He noted:

“It is unpleasant to question the sincerity even of an individual; and much more so to doubt the good faith of a solemn deliberative body. But, as a faithful historian, we are bound to state honest convictions, be they what they may. The General Assembly, in this instance, gave too much reason for the inference which many drew from their conduct on the occasion, that the call for a convention was a sham movement designed to amuse that portion of the citizens of the state, who were loud in their demands for a constitution and an extension of suffrage. Much of the language uttered in debate was of a bitter, sarcastic, and contemptuous character; and manifested a disposition on the part of the speakers, to resist, at all hazards, every attempt to meet the wishes of those who thought themselves aggrieved, and who demanded redress.”

Frieze also harshly criticized the leaders within the suffrage movement, referring to them as “political demagogues, with Thomas W. Dorr at their head; and who came in at the eleventh hour, to promote their own objects of private ambition.”

If Frieze was correct, and to a degree many agreed with him in 1842, then Thomas Dorr paid a handsome price for his ambition. Following sixteen months in exile Dorr returned to Rhode Island, where he was arrested, tried for treason, found guilty and sentence to life in prison. After eighteen months in prison, his health shattered, Dorr was released.

As noted, Frieze was an active member of the Rhode Island Suffrage Association when it was formed in February 1840, and he remained so until he left the organization the following year when he felt its leadership had been taken over. This most likely is what Frieze was referring to when he mentioned the entrance of “eleventh hour” demagogues. According to Frieze, the initial intent of the association was to make “use of memorials, petitions, and the ballot-box,” and if that failed it would be justified, as a last resort, to test the validity of its claims, either in Congress or in the Supreme Court. Frieze felt that the eleventh-hour demagogues ignored this original intent of the association. He wrote “that a few ambitious men who had become the chief counsellors of the suffrage party, the master spirit among whom, was THOMAS W. DORR, had resolved to revolutionize the State, and to form a government to suit themselves.”

Frieze felt that the purpose of the suffrage movement was to extend suffrage and not to embrace free or universal suffrage. As Frieze saw it suffrage extension was to be open to all native citizens of the United States and not, as he said, to “naturalized foreigners.” This is Frieze showing nativistic feelings for at no point does he refer to naturalized citizens as anything other than as naturalized foreigners. Dorr and his Democratic so-called “eleventh-hour demagogues” favored suffrage for naturalized citizens too. Moreover Dorr, even if many in his movement did not, favored suffrage for citizens of color as well.[2]

It is evident Frieze resented Dorr’s leadership in the suffrage movement, often calling him out in his book and in one instance mentioning him by name in all capital letters. He felt Dorr had “unconquerable obstinacy” due to his “tenacious adherence to the principle of universal suffrage” and an “indefatigable perseverance in any and every cause in which he might be engaged.”[3] Frieze felt these traits led Dorr to reject compromise with the state’s government, especially after the General Assembly in May 1842 appeared willing to call for another constitutional convention and even to allow the open election of delegates to the convention by an expanded electorate that did not consist of just landholders.

For the remainder of the 19th century, including after Dorr’s death, Dorr’s actions during the rebellion were held in low regard by Rhode Island’s propertied class and their entrenched interests, yet even Dorr’s enemies, Frieze included, recognized his many talents and uncompromising principles. As late as 1901, historian Arthur May Mowry wrote an account of the rebellion that still faulted Dorr for his actions when he carried the quest for political reform from discourse to the battlefield. Frieze too felt that Dorr went from revolution to rebellion when he decided to use military action on the evening of May 17, 1842 and led a force of nearly 250 pro-suffrage men in an attempt to overtake the state arsenal on the Cranston Road by force.

By the beginning of the 20th century the narrative began to change. Amasa Eaton first put the rebellion and Thomas Dorr in a positive light in his paper, “Thomas Wilson Dorr and the Dorr War” published in June 1909. Eaton said of , “A man is sometimes born, lives and dies so far in advance of his times, circumstances and surroundings that he is not understood or appreciated until a later day. Then the way opens for an appreciation of the principles for which he in vain contended. He may have had intellect, character, education that gave him insight into principles but dimly appreciated by those about him or which were ignored or denied because in conflict with selfish vested interest.”

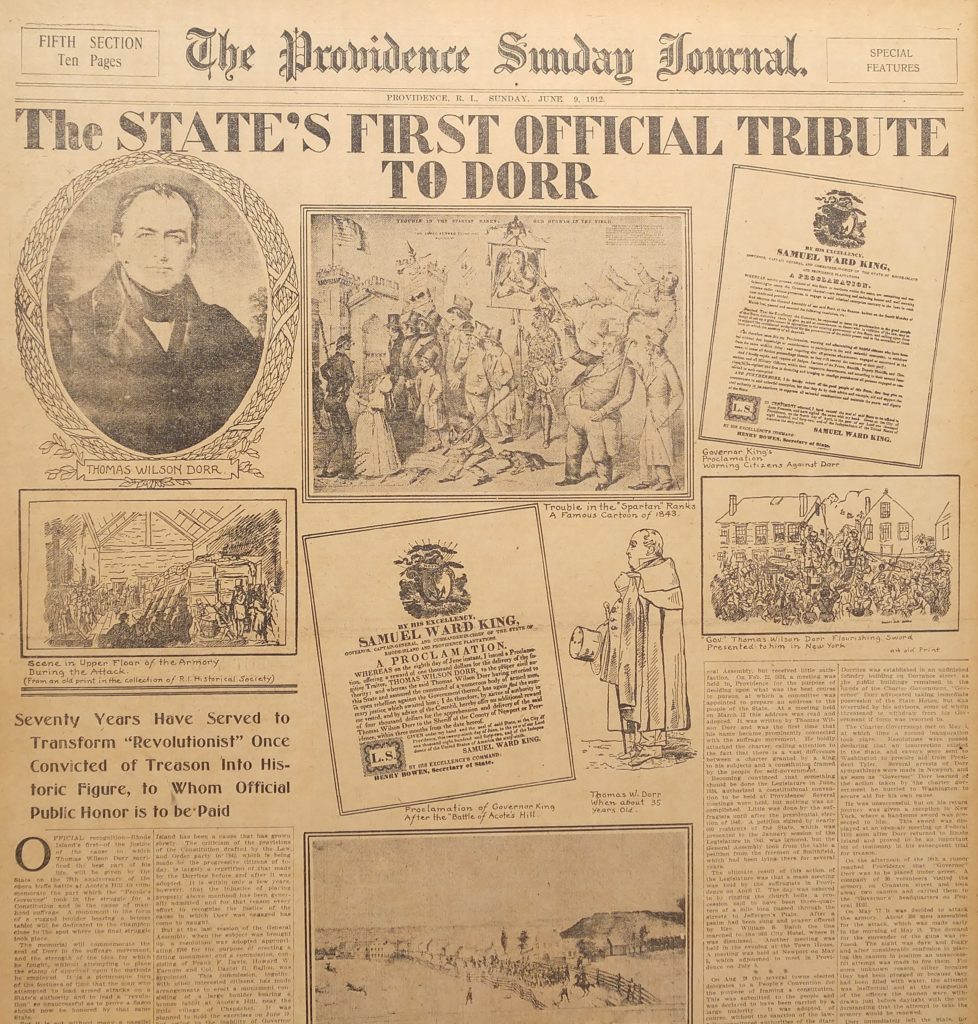

The Providence Journal, in its Sunday edition on June 9, 1912, ran a full page spread with numerous illustrations and bold lettering titled “The State’s First Official Tribute to Dorr.” This was a surprising turnaround as it was the Providence Journal that spewed much of the vitriol against Dorr and the suffrage movement in the columns of its paper in 1842.

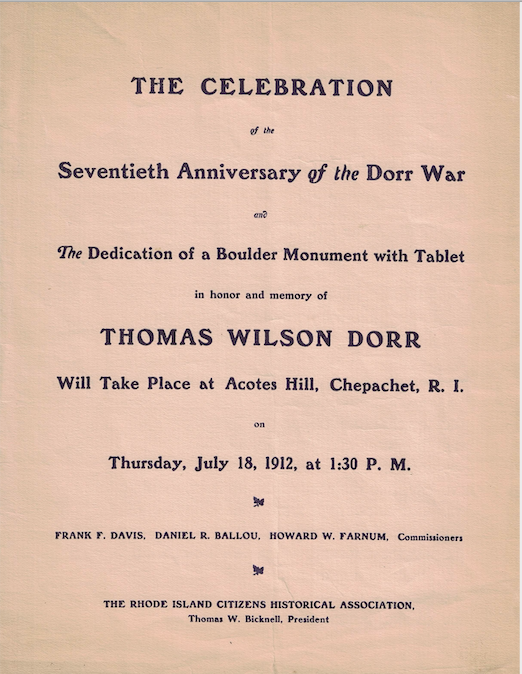

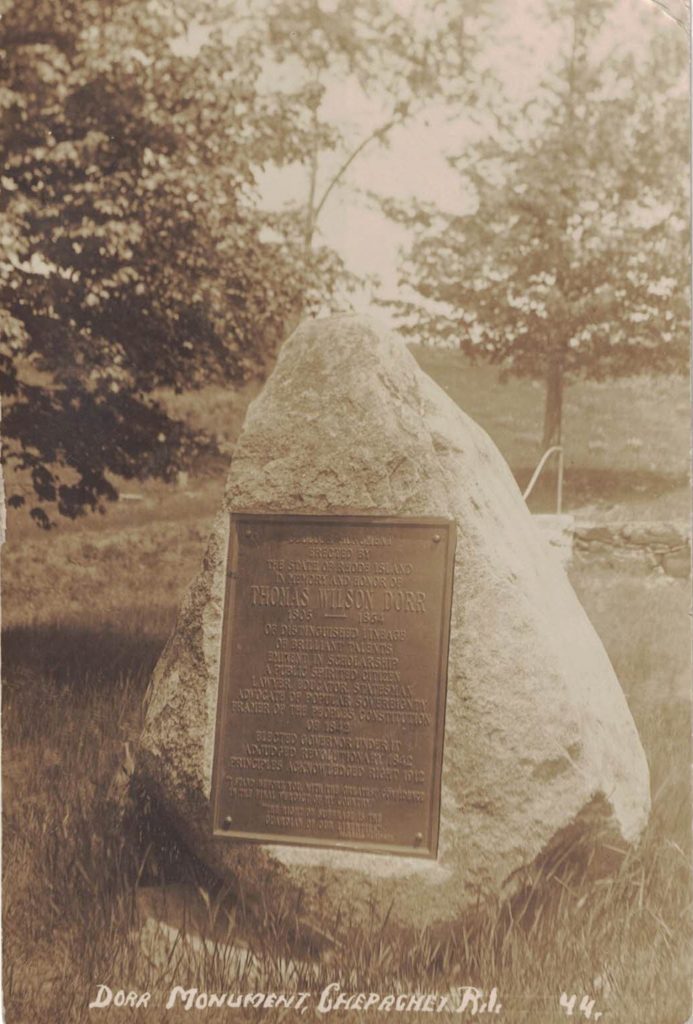

The following month the Rhode Island Citizens Historical Society Association held a celebration and dedication of a monument at Acotes Hill in Chepachet. Governor Aram J. Pothier was on hand to accept the monument on behalf of the state, and noted Rhode Island historian Thomas Bicknell gave the historical address.

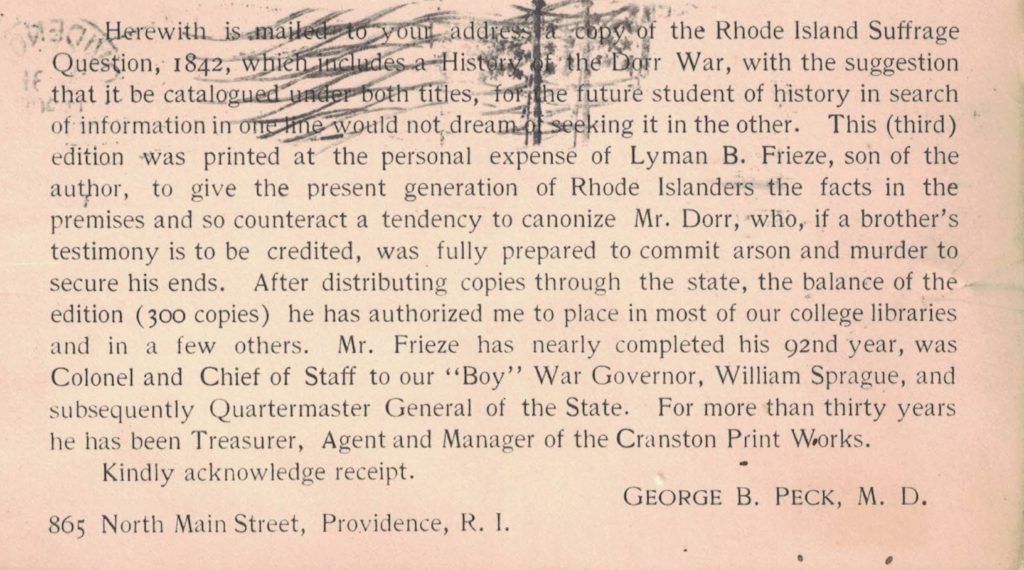

All this unexpected glorification of Dorr must have been too much to bear for Jacob Frieze’s son, Lyman, so much so that he had his father’s book reprinted by Providence printer Thomas Hamond in a small edition of 300 books [4] Lyman’s stated purpose as revealed in a postcard printed at the time of the book’s printing was to “give to the present generation of Rhode Islanders the facts in the premises and so counteract a tendency to canonize Mr. Dorr . . . .” Lyman Frieze’s efforts failed, however, to tarnish the achievements of Thomas Dorr or impede his apotheosis.

Dorr’s reputation continued to grow throughout the 20th century. In 1942 Providence Journal literary editor Winfield Townley Scott penned a poem, “The Sword on the Table,” that took a sympathetic look at Thomas Dorr. In a prefatory note, Scott said Dorr was “a brilliant lawyer, inept strategist, and a leader of great integrity.” He also suggested that “Dorr remains a Wilsonian figure in the history of American democracy,” referring to the democratic idealism of President Woodrow Wilson. This praise was a prophetic choice of words as Dorr’s middle name was Wilson.

Continuing further into the 20th century, on Rhode Island Independence Day, May 4, 1943, United States Senator Theodore Francis Green unveiled a portrait of Dorr at the State House. Up until that time no portrait of Dorr hung in the State House’s halls alongside those of Rhode Island’s other governors. Senator Green, recognizing Dorr’s integrity, said of Dorr, “he was incapable of compromise of principle. In that lay both the tragedy of his defeat then, and the glory of his triumph now.”

Adding to Dorr’s recognition, in 1954 a bronze maker was placed at Dorr’s grave at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence. It described Dorr as Rhode Island’s governor under the “People’s Constitution.”

Marker denoting Thomas Dorr as governor under the People’s Constitution at his Swann Point Cemetery gravesite (Russell DeSimone)

Scholarship on Thomas Dorr and his rebellion increased dramatically during the 1970s with the publication of Marvin Gettleman’s The Dorr Rebellion – A Study in American Radicalism 1833-1849 in 1973, George Dennison’s The Dorr War – Republicanism on Trial 1831-1861 in 1976, and Patrick Conley’s masterwork, Democracy in Decline – Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development 1776 – 1841 in 1977. All these accounts provided a favorable view of Dorr.

In 1992, on the sesquicentennial of the rebellion, a major exhibit was held at the Rhode Island Historical Society’s Aldrich House. Numerous programs were held to mark the anniversary and another book, The Broadsides of the Dorr Rebellion, co-compiled by this author and Daniel Schofield, was published by the Rhode Island Supreme Court Historical Society. Patrick Conley’s pamphlet, “No Tempest in a Teapot: The Dorr Rebellion in National Perspective,” was also published.

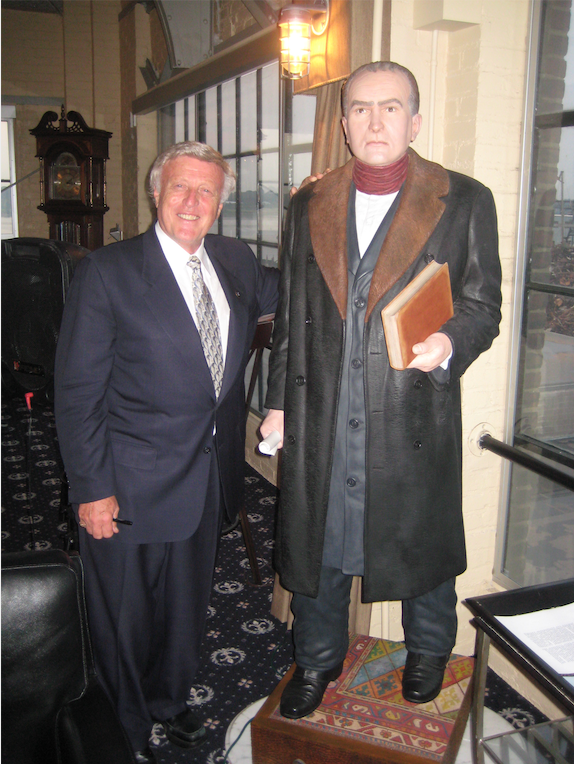

Further into the 21st century, the canonization of Dorr continued. Patrick Conley and his wife Gail commissioned a life-size statue of Thomas Dorr in 2001. The statue created by Rhode Island sculptor Joseph Avarista today stands at the entrance to the senate chamber at the Rhode Island State House. In addition, Providence College undertook the development of the Dorr Rebellion Project, an educational website including a short-form documentary, image gallery, correspondence (to and from Thomas Wilson Dorr), interviews with Dorr scholars and supporting curricular materials. This website can be viewed at http://library.providence.edu/dorr/. In 2013 Erik Chaput’s outstanding book, The People’s Martyr – Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion, was published. Judging from its title, if Dorr truly sacrificed himself in the cause of the people, then martyrdom, often a requisite for sainthood, would certainly qualify Dorr for canonization.

Surely, Lyman Frieze’s fear of the canonization of Dorr had come true. Lyman would have strongly disapproved with the conclusions of these later day historians, much as his father disapproved of Dorr’s actions in 1842.

Rhode Island Historian Laureate Patrick Conley with the statue of Thomas Dorr he commissioned before it was moved from the Fabre Line Club to the State House.

Amasa Eaton closed his 1909 paper by noting, “high upon the roll of Rhode Island’s great men will stand forever the name of the political reformer and public benefactor, Thomas Wilson Dorr.” While Dorr’s actions came to be looked upon favorably by 20th and 21st century chroniclers of the rebellion, perhaps it was Noah Arnold, a contemporary of Dorr, who said it best. Arnold first elevated Dorr to a sort of sainthood with the lines, “His name will go down to posterity, hand and hand with Roger Williams, Roger Williams as the great defender of soul liberty and religious freedom: Thomas Dorr as the great defender of political freedom and the rights of Man.”[5] For any Rhode Islander there can be no greater tribute than to be compared favorably to Roger Williams. If there is a pantheon of Rhode Island’s greats then we must look there for Thomas Wilson Dorr.

NOTES

[1] Another suffrage work attributed to Frieze was the small pamphlet “Facts for the People: Containing a Comparison and Exposition of Votes on Occasions Relating to the Free Suffrage Movement in Rhode Island,” published in 1842. Edwin Maxey, in his “Suffrage Extension in Rhode Island Down to 1842,” published in 1908, said of Frieze’s book, “Frieze has told the story of Dorr’s rebellion, but it was written in 1842, and is told in a popular way and from an intensely partisan standpoint.” [2] Black people had been disenfranchised in Rhode Island in 1822 at a time when many other northern states were also disenfranchising their citizens of color. [3] Dorr’s obstinacy and perseverance were well known. His friends attributed it to the fact he was a man of high principles and unyielding when he felt principle was at stake. Edwin Maxey, in his pamphlet on the Dorr Rebellion, noted “Dorr was not at all the kind of man to stop until something heavy was placed in his way, and not even then unless it was so heavy and hard that he could by no possibility remove it or surmount it.” [4] Lyman B. Frieze (1825 – 1917) was a seventeen-year-old teenager at the time of the Dorr Rebellion Accordingly, he had firsthand knowledge of the rebellion’s events. He served on Governor William Sprague’s staff and in 1863 was appointed by President Lincoln as Collector of Internal Revenue for Rhode Island. A lifelong Republican, for a time he was the Rhode Island representative to the National Republican Committee. [5] Taken from Noah Arnold’s essay, “A History of Suffrage in Rhode Island,” in Narragansett Historical Register, vol. VIII (1890). Other 19th century pro-Dorr accounts included Frances Harriet Whipple Green’s Might and Right (1844), and Dan King’s The Life and Times of Thomas Wilson Dorr (1859).