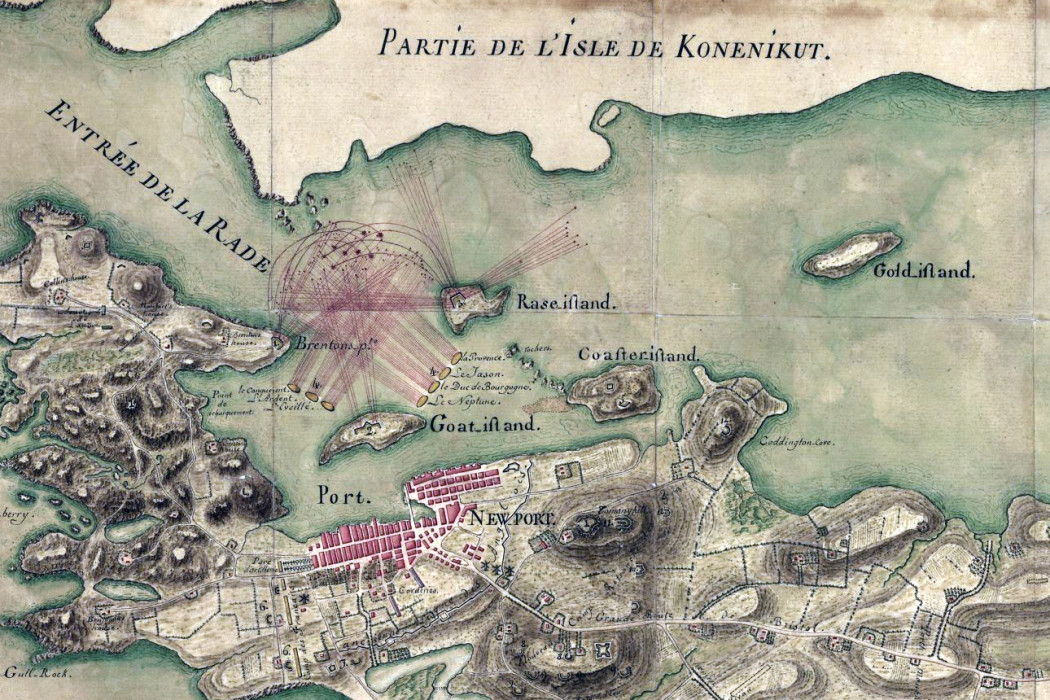

On July 10, 1780, a French fleet of seven ships of the line and four frigates under Admiral Chevalier de Ternay, along with thirty-six transport vessels carrying about 6,000 French soldiers commanded by Lieutenant General Comte de Rochambeau and their supplies, arrived off of Newport, Rhode Island. The plan was to use the port town as the primary base of French operations in the United States. Meanwhile, the British commander in chief in North America, Sir Henry Clinton, felt that if the combined forces of the British navy and army could attack Newport after the French arrived but before they established their defenses, they could gain a crushing victory that might take France out of the war.

As mentioned in a prior article of mine, with the recent popularity of spies in the Revolutionary War, led by AMC’s TURN cable television series and the bestselling book George Washington’s Secret Six: the Spy Ring that Saved the American Revolution,[1] the impact that spies had on the outcome of campaigns and other aspects of the war has sometimes been exaggerated. I focus on two examples in my recently published book, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island.[2] The second example, and the subject of this article, is the role of the Culper spy ring in warning General Rochambeau of Clinton’s plans. (The Culper spy ring is also the subject of TURN and Secret Six.) In this respect, the Culper spy ring performed highly dangerous work brilliantly, but there were other sources who conveyed the same intelligence in a timely fashion.

Prior to the arrival of the French at Newport, General George Washington called on the services of his successful Culper spy ring, based in Long Island, for intelligence of Clinton’s movements. “As we may every moment expect the arrival of the French fleet a revival of the correspondence with the Culpers will be of very great intelligence,” wrote the commander in chief to Major Benjamin Tallmadge, the talented Continental officer who handled the spy ring.[3] Tallmadge first contacted Captain Caleb Brewster, who took his sailboat across Long Island Sound from Connecticut to Setauket, Long Island. Finding his and Tallmadge’s boyhood friend and spy, Abraham Woodhull, sick in bed, Brewster then sought out Austin Roe, a tavern keeper in East Setauket. Roe rode almost nonstop to New York City and met with the ring’s key spy, Robert Townshend, a dry goods storeowner and part owner of a coffeehouse frequented by sometimes loose-lipped British officers.

Townshend soon learned of Clinton’s large ground force gathering on the north side of Long Island and passed on a letter containing the explosive intelligence to Roe. The same day, Roe rode the fifty-five miles back to Setauket and delivered the letter to a still ailing Woodhull. Woodhull forwarded the letter to Brewster, along with (as historian Alexander Rose put it), “the most urgent note he ever penned.”[4] Woodhull advised Brewster, “The enclosed [from Townshend] requires your immediate departure this day by all means, let not an hour pass for this day must not be lost. You have news of the greatest consequence perhaps that ever happened to your country.”[5] Brewster rushed back across Long Island Sound to the Connecticut shore and, bypassing Tallmadge to speed delivery of the message, dispatched a rider to Washington’s headquarters to the west.

At Preakness, New Jersey, Alexander Hamilton, one of the commander in chief’s young aides, received the message the afternoon of July 21. The time of Washington’s initial request to Tallmadge to Hamilton’s receipt of the intelligence was a mere ten days.

Hamilton read Townshend’s intelligence that the British were aware of the expected arrival of the French fleet at Newport; that nine powerful British warships had departed from New York and had “sailed for Rhode Island;” and that “8,000 troops are this day embarking at Whitestone,” Long Island, with a design to attack the French at Newport.[6] Even though Washington was away, Hamilton immediately penned a letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, who had left Washington’s headquarters on July 19 for Newport in order to help coordinate military affairs between Rochambeau and Washington. The young colonel stated that he had “just received advice from New York through different channels that the enemy are making an embarkation with which they menace the French fleet and army. Fifty transports are said to have gone up the Sound to take in troops and proceed directly to Rhode Island.”[7] A bit after 4:00 p.m., he sent an express rider eastward to catch up with Lafayette.

At the time, the Continental army was camped west of the Hudson River. When Washington returned to his Preakness, New Jersey, headquarters, he used the Culper spy ring’s intelligence to prepare for a diversionary attack outside New York City at the key point of Kingsbridge, New York, in the hope of causing Clinton to call off his planned expedition against Newport.[8]

On July 18, Clinton received shocking news: the French fleet had arrived outside Narragansett Bay on July 10.[9] To Clinton’s dismay, not only had Royal Navy ships lost track of the opposing fleet, they had not become aware of Ternay’s arrival in Newport for a full week. Still, Clinton wanted to attack Newport immediately.

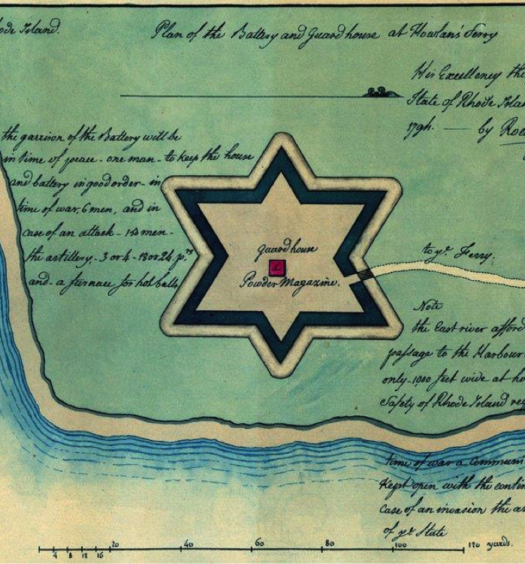

The French took time getting their defenses in order. Starting on July 13, the healthy troops began to disembark. By July 15 they were all ashore, hard at work repairing the forts abandoned by the British nine months earlier and building new ones at the south end of Aquidneck Island. On July 16 and 17 the approximately 1,500 sailors and 800 soldiers and marines sick with scurvy and other illnesses contracted during the seventy-day Atlantic crossing were disembarked and conveyed to nearby temporary hospitals.[10] The next important matter was getting ashore the artillery, which was crucial for fending off any land or sea attack. On July 21, ten days after their arrival, all of the field artillery was on land and placed in position.[11] Jean-François-Louis Crévecoeur, then serving as a lieutenant in a French artillery company, recorded that the town’s impressive coastal defenses included seventy artillery pieces consisting of “twelve 24-pounders, eight 16-pounders, eight 12-pounders, sixteen 4-pounders, two 8-inch howitzers, eight 6-inch howitzers, six 12-inch howitzers, six 12-inch mortars and four 8-inch mortars.”[12] “In twelve days’ time,” wrote Rochambeau in his memoirs, the defense of Newport was “rendered respectable.”[13]

The first word received by General Heath of Clinton’s plans came in the sloop Gates,whose captain boldly sailed it from Stonington, Connecticut, evading the British blockade of Narragansett Bay and arriving at the Newport wharves about 3:00 p.m. on July 24. The sloop carried Colonel Samuel B. Webb, a colonel of a Continental army regiment named after him, who was then on parole as a former prisoner. After he had been captured on a transport vessel in Long Island Sound during a mission and brought to Newport in December 1778, Webb had been generously and quickly paroled, and allowed to reside at his home in Wethersfield, Connecticut. On learning of the arrival of the French fleet from Major Tallmadge, Webb, along with four of his Connecticut friends, had decided to sail to Newport and visit the newly-arrived French officers, almost as a lark.[15] However, it was a risky adventure, since their boat could have been intercepted by a British frigate.

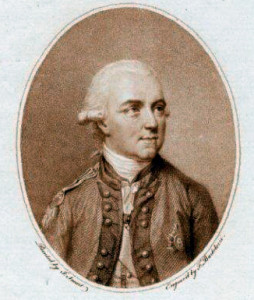

In the afternoon of July 25, the two allied commanders at Newport—Major General William Heath of Massachusetts, the head of American forces in the Rhode Island theater, and General Rochambeau—received the first intelligence of Clinton’s attack plans. But, contrary to the conclusions of some early historians covering the famous Culper spy ring, the first word did not arrive from the express rider dispatched by Alexander Hamilton. This rider never caught up with Lafayette prior to the French general arriving in Newport on July 24.[14]

After leaving the central Connecticut coast on July 18 and leisurely making their way eastward, Webb and his friends arrived in Stonington, Connecticut, on July 23 and heard the stunning news of Clinton’s imminent attack on Newport. When they arrived in Newport the next day, they brought with them a written statement from Clark Pratt, who had left Long Island on July 23, probably by whaleboat. On Long Island, Pratt had met a man who had departed New York City on July 21. This man had informed Pratt that Admiral Graves had arrived from England with his ships of the line, that he had landed his sick sailors, recruited 1,000 volunteers to replace them and had proclaimed that Newport was their destination. The same man informed Pratt that British troops had embarked onto ships carrying them to the eastward, that they numbered 10,000, and that they were on transports poised to make the perilous passage through Hell Gate in the East River and onward to Newport. The author of the report stated that both Pratt and the man who had been at New York City “are both known in Stonington to be of veracity.”[16] Webb’s actions, delivering valuable intelligence against the interests of the Crown, violated the terms of his parole, but he felt that the news was too important to leave to others.

Heath then immediately penned the following to Rhode Island’s Governor William Greene:

Intelligence this moment received by the way of Long Island that Sir Henry Clinton intends to make an attempt on Rhode Island with a large body of troops, it is said ten thousand men. His Excellency Count de Rochambeau requests that he may be immediately reinforced with two thousand militia. I request that you would order fifteen hundred of that number properly officered, armed and accoutered to rendezvous without the least delay at Tiverton. General Rochambeau says that in six or seven days, he shall be perfectly secure without them, and they may return home at that time…The account says the enemy has embarked.[17]

Heath wrote a similar letter to Brigadier General George Godfrey—who commanded Massachusetts militia hailing mainly from the neighboring counties of Bristol, Plymouth and Barnstable—requesting an additional 800 soldiers.[18]

The message from the Culper spy ring was not the second warning to arrive in Newport either. That honor went to Colonel Henry Babcock from Westerly, Rhode Island, who had in 1776 commanded a Rhode Island regiment, but had been sacked by the state’s general assembly. Babcock, it seems, had met the same man who had recently arrived from Long Island at Stonington. After repeating the same intelligence, Babcock added, “The person who brought me the above intelligence from Long Island is a young man of undoubted veracity and son to a member of the Assembly of New York State, who fled from Long Island and lived a year without his family in my house at Stonington, and he may be relied upon. He says the person who informed him is a man of character.” Babcock sent his children’s tutor, a Mr. Whitman, to deliver the message. Despite the weighty matter addressed in his letter, Babcock made a trivial request of Heath to allow Whitman to board Ternay’s flagship, “as Mr. Whitman was never on board a ship-of-the-line.”[19] Babcock sent another message the next day, after receiving a confirming report from another man who had just departed from Long Island and arrived at Stonington, as well as word from another “gentleman” who added that “the British officers flatter themselves of entirely captivating both the Fleet and Army of His Most Christian Majesty.”[20]

The express rider carrying Hamilton’s dispatches from Preakness, New Jersey, finally arrived at Lafayette’s quarters in Newport just before midnight on July 25. While he was writing a letter to Governor James Bowdoin of Massachusetts, requesting more militia, General Heath penned the following postscript: “P.S. 12 o’clock at night. By a letter this moment received from headquarters, the intention of the enemy against this place is confirmed.”[21] After the dispatch from Colonel Hamilton arrived, Heath took the threat even more seriously and issued requests for all of the militia of Rhode Island and even more militia from Massachusetts to gather at Tiverton or Bristol.

Meanwhile, by the morning of July 28, more than seventy transport vessels carrying Clinton and his troops were anchored in Huntington Bay off Long Island. The soldiers, broiling in the summer sun, waited impatiently for orders to proceed with the attack on Newport.[26] But the orders never came.

In the next few days, other reports of Clinton’s preparations to invade Newport arrived at Heath’s headquarters. One came from Major Benjamin Tallmadge, who sent his message separately, in case Hamilton’s messenger had been waylaid.[22] Hamilton, as a result of “receiving advices through different channels from New York” of the British embarkation, sent a second dispatch to Newport on July 21, this one addressed to General Rochambeau.[23] Major General Robert Howe, based in the Highlands of New York State, received accurate intelligence of Clinton’s intentions from a “variety of agents,” and, on July 23, dispatched to Heath an express, which arrived in Newport probably on July 27 or 28. Brigadier General Samuel Parsons, based in Danbury, Connecticut, wrote Lafayette on July 24 of British naval and army movements, which led him to “believe the enemy designs to attack the ships and troops at Rhode Island.”[24] On July 28, Heath wrote Governor Greene, “The intelligence received here of the motions and probable intentions of Sir Henry Clinton was from Colonel Hamilton at headquarters, Major General Howe, General Parsons, Major Tallmadge, some gentlemen at Long Island, and other sources from thence.”[25]

Recent historians of the Culper spy ring have emphasized that the intelligence provided by the Culper spy ring led Washington to prepare a diversionary attack, which they say caused Clinton to drop his Newport plans and rush back to defend New York City.[27] In fact, according to the historian who has studied the matter most closely, the British decision to call off the attack was due more to the lack of coordination between Clinton and the senior admiral of the Royal Navy in North America, Marriott Arbuthnot.[28] These stumbles are also described in some detail in my Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island book.[29] Thus, it appears to be overstating the case that Washington’s diversionary efforts alone halted Clinton’s plans.

In addition, as this article has shown, word of Clinton’s preparations came, as Hamilton wrote on July 21, from a number of “different channels.”[30] One of the lessons of this episode is to consider the variety of intelligence sources at Washington’s and Heath’s disposal. The Culper spy ring, as amazing as it was, cannot be credited alone.

One early historian of the Culper spy ring, John Bakeless, credited the Culper spy ring with giving the French in Newport time to establish their defenses.[31] But, as this article has shown, French defenses were already well established by July 22. In addition, intelligence reports from Colonels Webb and Babcock arrived during the day on July 25 at Newport, ahead of the Culper spy ring’s report sent by Hamilton.

The intelligence brought by Webb, Babcock, the Culper spy ring and others did lead General Heath to call out thousands of militiamen and spurred Rochambeau to hurry improving the preparations of Newport’s fortifications. These militiamen and improvements in Newport’s defenses were noticed by Loyalist spy Thomas Hazard and British naval observers, which helped to discourage Admiral Arbuthnot from cooperating with Clinton, forcing the commanding British general to drop his plans against Newport.[32] Accordingly, these various American spy efforts played a substantial role in thwarting the British attack on Newport.

/// Featured image at top: French map showing the firing lines of the French ships lined up outside Newport harbor and the French fortifications (view full size map). Source: Library of Congress

[1] Brian Kilmeade and Don Yeager, George Washington’s Secret Six: The Spy Ring that Saved the American Revolution (New York, NY: Sentinel, 2013).

[2] Christian McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014). My first article on this topic in the Journal of the American Revolution is “Ann Bates: British Spy Extraordinaire,” December 1, 2014.

[3] Quoted in Alexander Rose, Washington’s Spies: The Stories of America’s First Spy Ring (New York, NY: Random House, 2006), 289.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Quoted in ibid, 289–90.

[6] Quoted in ibid., 291.

[7] A. Hamilton to M. Lafayette, July 21, 1780, in Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1961), 2:362–63 (the editor noted that the letter was sent from Preakness, New Jersey). For Washington’s headquarters being at Preakness, New Jersey on July 21 and 22, 1780, see general orders issued from headquarters on those dates in John Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1931), 19:222–23. For Hamilton writing his letter to Lafayette at 4:00 p.m., see id., 223, n. 91.

[8] G. Washington to C. Rochambeau, July 27, 1780, in Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of George Washington 19:268; G. Washington to W. Heath, July 31, 1780, in id., 282.

[9] Henry Clinton Recollections, in William B. Willcox, ed., The American Rebellion, Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaign, 1775-1782 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1954), 199; see also Diary Entry, July 25, 1780, in William H. W. Sabine, ed., Historical Memoirs of William Smith (New York, NY: New York Times and Arno Press, 1969), 311 (“I perceived by it that on the news last Tuesday [July 18] from Montauk [in eastern end of Long Island] of the arrival of the French Fleet, 10th and 11th instant…”).

[10] C. Rochambeau to W. Heath, July 25, 1780, William Heath Papers, reel 16a, Massachusetts Historical Society; Robert W. Kenny, Town and Gown in Wartime: A Brief Account of the College of Rhode Island, Now Brown University, and the Providence Community During the American Revolution (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1976), 29 (quoting Marquis de Chastellux); Diary Entry, July 1780, in Harold C. Rice, and Anne S. K. Brown, eds., “Crévecoeur Journal,” inAmerican Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1972), 1:18 (troops disembarked July 14 and 15); Diary Entries, July 10-15, 1780, in Rice and Brown, eds., “Verger Journal,” ibid., 1:120; Diary Entries, July 30, 1780, in Evelyn M. Acomb, ed., The Revolutionary Journal of Baron Ludwig von Closen, 1780-1783 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1958), 28 (Closen’s regiment disembarked on July 13); Count William de Deux-Ponts Recollections, in D. K. Abbass, Rhode Island in the Revolution: Big Happenings in the Smallest Colony (Washington, D.C.: USDI National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program, 2006), 1:469 (“The grenadiers and chasseurs were the first to land…They were followed on the 14th and 15th by the well troops, and the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th were given up to landing the sick.”).

[11] Lee, B. Kennett, The French Forces in America, 1780-1783 (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1977), 49.

[12] Rice and Brown, eds., “Crévecoeur Journal (July 1780),” American Campaigns of Rochambeau1:18.

[13] Quoted in Edward M. Stone, Our French Allies in the Great War of the American Revolution(Providence, RI: Providence Press, 1884), 204.

[14] For the arrival of Lafayette on July 24, see William Heath, Heath’s Memoirs of the American War (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries, 1970) (first published in 1798), 259. None of Lafayette’s correspondence indicates that the French general received Hamilton’s letter prior to about midnight July 25.

[15] S. Webb to J. Barrell, July 16, 1780, in Worthington C. Ford, ed., Correspondence and Journals of Samuel B. Webb (New York, NY: Wickersham Press, 1893), 2:274–75.

[16]W. Heath to Admiral Ternay, July 24, 1780, William Heath Papers, reel 16a, Massachusetts Historical Society, with enclosure on Intelligence, July 24, 1780. Alexander Rose, in his fineWashington’s Spies, at least addressed the possibility that the Americans may have learned about Clinton’s plans from a source other than the Culper spy ring. He writes in a footnote, “About a week after the Culpers’ report, Hamilton received a note from the mysterious agent ‘L.D.,’ who sounded as if he lived somewhere outside the city in what today would be Queens. Nothing more is known of him. It is officially dated July 21 in the Washington Papers, but it was written over the course of four days as the author updated it, the last entry being written on the twenty-fifth. The first section was written in the evening of July 21…[L.D.’s] report is accurate, but late, too late to be of any use.” Id., 328, n. 88 (citing Intelligence Report, L.D. to G. Washington, July 21–25, 1780, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress). It does not appear that L.D.’s report was ever sent to General Heath in Newport, probably because it was duplicative of intelligence received earlier at Washington’s headquarters.

[17]W. Heath to W. Greene, July 25, 1780, Letters to the Governor, Rhode Island State Archives. The time of the letter is set as 4:00 p.m. The reference to 10,000 British soldiers is also an indication that Heath at this time was relying on intelligence from Stonington, and not from the Culper spy ring, which had reported the number of British troops (more accurately) at 8,000.

[18]W. Heath to General Godfrey, July 25, 1780, William Heath Papers, reel 16a, Massachusetts Historical Society (timed 5:00 p.m.).

[19] H. Babcock to W. Heath, July 24, 1780, in ibid. (writing from Westerly).

[20]H. Babcock to W. Heath, July 25, in ibid. (writing from Stonington; this message was carried by Colonel Babcock’s son).

[21] W. Heath to J. Bowdoin, July 25, 1780, ibid. The next letter Heath wrote, to Governor Greene, he said, “I send you the letter that Mr. Lafayette has received from an adjutant who is an intimate friend of General Washington [meaning Major Benjamin Tallmadge]. He asserts the certainty of Clinton’s getting on board with 8,000 men to come and joint the fleet.”

[22]See B. Tallmadge to G. Washington, July 22, 1780, George Washington Papers, reel 68, Library of Congress (from Croton on the Hudson River, 6:00 p.m.).

[23] G. Washington to C. Rochambeau, July 21, 1780, in Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of George Washington 19:223 (in Hamilton’s handwriting).

[24] S. Parsons to M. Lafayette, July 24, 1780, in William Heath Papers, reel 16a, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[25]W. Heath to W. Greene, July 28, 1780, Letters to the Governor, Rhode Island State Archives. There are other intelligence reports in Heath’s and Washington’s files as well. One report found in Heath’s files, which is undated and unsigned, is detailed and appears to have been written about July 22. Undated and unidentified intelligence, item #97, William Heath Papers, reel 16a, Massachusetts Historical Society. Elias Dayton, writing from Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth), New Jersey, also wrote an accurate report of British intentions on July 21. He may have had difficulty getting it timely delivered to Washington at his headquarters near the Hudson River. E. Dayton to Unknown, July 21, 1780, George Washington Papers, reel 68, Library of Congress.

[26] Diary Entry, July 28, 1780, in Ira D. Gruber, ed., John Peebles’ American War: The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), 398. Most of the British army troops had arrived at Frog’s Neck on July 23, embarked on the arriving transports on July 24 and 25 and made it through Hell’s Gate on July 25 and 26. Ibid., 396–97.

[27]See, e.g., Rose, Washington’s Spies, 190–92; Kilmeade and Yeager, George Washington’s Secret Six, 124–26; Kenneth A. Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2014), 193–94.

[28] See William B. Willcox, “Rhode Island in British Strategy, 1780–1781,” Journal of Modern History 17:4, 311 (December 1945).

[29] See McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 79-96.

[30] A. Hamilton to M. Lafayette, July 21, 1780, in Syrett, ed., Papers of Alexander Hamilton 2:362.

[31] See, e.g., John Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1975), 235–36.

[32] McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 91-96.