The sixteenth, seventeenth and the first part of the eighteenth centuries were times of great turmoil in Europe. They were characterized by a number of wars, such as the Thirty Years War, which ostensibly were fought for political purposes but were really religious wars because the victors sought to impose their religious beliefs on their subjects. In Great Britain as well, conflicts occurred even within Protestant groups, between the established Anglican Church and “dissenters” (mostly Puritans). British kings and queens supported the Anglican Church and sometimes punished dissenters. Consequently, people who disagreed with their ruler’s beliefs sometimes sought greener pastures.

The Pilgrims arrived in America at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620, while the Puritans founded Boston in 1630. Although they came for religious freedom, they did not provide it to their own people. The Puritans expelled Roger Williams in 1636 and Anne Hutchinson in 1638 because of disagreements over religious beliefs.

Roger Williams purchased land from the Narragansett Indians and founded Providence. Anne Hutchinson and her group of dissenters purchased property on the northern end of Aquidneck Island (then known as Rhode Island) and founded the town of Portsmouth. She was the first woman to be a founder or co-founder of a town in America. A group headed by William Coddington broke off from Hutchinson’s band and founded Newport. Roger Williams, with his connections in England, was able to obtain a charter for the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He based the colony on the “lively experiment” of religious toleration and separation of church and state. As religious immigrants sought to benefit from this unique approach in the Western world, many flocked to Newport, which became known, at least among Puritans, as a cesspool of heresy.

Five major religious denominations dominated Newport during the colonial period:

Church of England (Anglican)

Congregational Church

Baptist Church

Judaism

Society of Friends (Quakers)

Catholics were not, however, welcome. Many colonists came to America to escape religious persecution, particularly from the Inquisition, which was run by the Catholic Church. King Louis XIV, the Sun King, tried to conquer all of Europe in the name of Catholic Church. King James II and his ministers made efforts to convert subjects back to the fold of Catholicism. For British Protestants, Catholics were anathema. To keep them out of power, in 1719 the Rhode Island General Assembly enacted a law requiring that generally any voter had to: (1) be male, (2) be a Christian (BUT NOT A CATHOLIC), and (3) own property worth at least $134. As Patrick T. Conley has written, this exclusion of Catholics (and Jews) was “a violation of the spirit, if not the letter, of the Charter of 1663.”[1]

Anti-Catholic bigotry was centered in the political and legislative domains and rarely erupted into sectarian violence seen in other places. The divisions were nonetheless deep and long-lasting, particularly when the Irish, who were mainly Catholics, started arriving in Newport in large numbers in the early nineteenth century. They came primarily to work on the construction of Fort Adams, to work in the mansions that were beginning to be built, and to escape the Irish potato famine. Anti-immigration policies were rooted in anti-Catholic bigotry.

St. Mary’s Parish, the first Catholic parish in Newport, was founded in 1828 but the church building was not constructed until 1848-52.

The first Catholic mass in Rhode Island is generally believed to have been celebrated when the French army under the Count de Rochambeau arrived at Newport in July 1780. It is commonly believed that it was celebrated at the Colony House, the largest building in the city at the time. However, as we shall soon see, in fact it was celebrated at the Baptist Church.

The French forces, comprising about 6,156 soldiers and 4,416 sailors, were mostly Catholic but included Huguenots (French Protestants), Lutherans (mostly from the Alsace), and men of other faiths. Each regiment and ship usually had one or more chaplains.

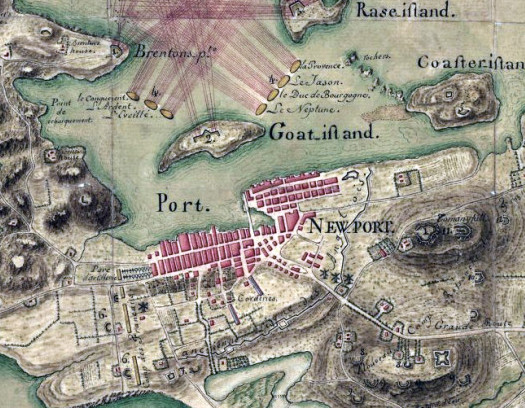

The troops began disembarking at Wood’s Castle on Sachuest Point on July 13, 1780 and had finished setting up camp by the 16th. (For more on the French landings, see my prior article: http://smallstatebighistory.com/identifying-french-landing-site-newport/.)

About 800 troops were ill with scurvy and other diseases after the 72-day crossing, so the first order of business was to set up hospitals. Rochambeau’s order book initially mentions a hospital in Newport on July 20, 1780 and specifically states that it was at the Baptist meetinghouse. Other hospitals were set up at Poppasquash Point and Providence (University Hall at what is now Brown University). The French army began posting a daily guard at the hospital at the Baptist meetinghouse on July 20. The guard consisted of a sergeant, a corporal, and 12 privates. The guard was changed daily during the entire duration of the French occupation.[2]

The French army under Count de Rochambeau arrived at Newport on July 13, 1780. Most, but not all, of the officers and soldiers were Catholics.

A guard of similar size was posted at Wood’s Castle. Louis-François-Bertrand du Pont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdière, General Rochambeau’s nephew and aide-de camp, identified this location as the landing site and anticipated that it might be the location of a possible British landing and attack on the city.[3] This site was also used for war games during the month of October to relieve the boredom of the troops. Another larger guard was placed at the William Vernon house, on Clarke Street, which served as the Count de Rochambeau’s headquarters. There was also a general guard of a captain, a lieutenant, and 50 men placed around the camp.

Claude Blanchard, the Commissary of the French Auxiliary Army, recorded in his diary that Rochambeau attended mass at the hospital on July 23, 1780. As the only hospital in Newport specifically mentioned by any of the French diaries, the first mass must have been celebrated at the Baptist meetinghouse, then located at the corner of Spring and Sherman Streets.[4]

The Comte de Charlus’s diary mentions another mass that was celebrated on August 12, when a band of Iroquois from New York came to visit Rochambeau and to render honor to the king of France.[5] The Iroquois wanted to attend mass but no building could accommodate everybody; the mass was celebrated in the middle of the army camp (probably in the area between Freebody Park and Sylvan Terrace).

This photo shows the First Baptist Church, at the corner of Spring and Sherman Streets in Newport, around 1906. This Greek Revival building replaced an earlier one that was built about 1737. It is believed that the first Catholic mass in Rhode Island was performed at the earlier building in 1780 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Another important mass was said at Admiral Charles Louis d’Arsac Chevalier de Ternay’s funeral on December 16, 1780. None of the diaries note where the mass was said. It was too cold to have it outdoors and no building was large enough to accommodate everybody, so perhaps only representatives from the various units attended the funeral mass. The body was buried in the cemetery at Trinity Church (which was Anglican) and troops lined the entire route, shoulder to shoulder on both sides of the street, from Hunter house, de Ternay’s headquarters, to the gravesite. The grave still exists.

The presence of the French army in Newport and its shared struggle against Great Britain changed the minds of many Rhode Islanders about Catholics. Even before the American Revolutionary War had ended, in February 1783 the General Assembly removed the prohibition against Catholics imposed in 1719 by giving members of that religion “all the rights and privileges of the Protestant citizens of this state.”[6]

President Washington replied to a letter, on March 12, 1790, from a five-person Catholic contingent congratulating him on his election as president. He acknowledged the claims of Catholic citizens to equality and added, “I hope to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality.” This was five months before his famous letter to the Friends of Touro Synagogue on August 21, 1790 in which he declares that “the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction to persecution no assistance.”

Reenactors of French regiments pose in front of a statue of General Rochambeau at King’s Park near Fort Adams. The author stands in the back row third from the right (Norman Desmarais)]

Ironically, Rhode Island is now the most Catholic state in the nation with 42 to 44% of the population identifying themselves as Roman Catholics.

[Banner image: Reenacators of French regiments pose in front of a statue of General Rochambeau at King’s Park near Fort Adams. The author stands in the back row third from the right (Norman Desmarais)]

Notes

[1] Conley Patrick T. and Robert G. Flanders, The Rhode Island State Constitution: A Reference Guide (Greenwood Publishing, 2007), 8. [2] Armée de Rochambeau, Livre d’Ordres Contenant Ceux Données Depuis le Débarquement des Troupes à Newport, Archives Departementales de Meurthe et Moselle. [3] Journal de l’armée aux orders de Monsieur le comte de Rochambeau pendant les Campagnes de 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, Bibliothèque nationale de France. [4] Blanchard, Claude, The Journal of Claude Blanchard, Commissary of the French Auxiliary Army sent to the United States during the American Revolution, Translated and edited by Thomas Balch (Albany, N Y: J. Munsell, 1876 [Reprint by New York Times and Arno Press, 1969]. [5] Charlus, Comte de, “The Iroquois Visit Rochambeau at Newport in 1780: Excerpts from the Unpublished Journal of the Comte de Charlus, by Durand Echeverria,” Rhode Island History 11 (July 1952), 73-81. [6] Quoted in Conley and Flanders, The Rhode Island State Constitution, 14. [7] See Conley, Patrick T., “Washington’s Open Letter of March 12, 1790 to American Catholics,” http://smallstatebighistory.com/washingtons-open-letter-march-12-1790-american-catholics/