The Great Gale of 1815 was one of the three strongest hurricanes ever to hit Rhode Island. Communities throughout the state suffered damage. This article quotes from three histories containing descriptions of the Great Gale of 1815’s impact on Newport, Providence, Narragansett, South Kingstown, and Tiverton. Slight edits were made to the original to use modern grammar, punctuation and usage.

The death toll from the storm, based on the excerpts below, was as follows:

Newport: 5

Providence: 2

Narragansett: 10 (5 adults and 5 children)

Total: 17

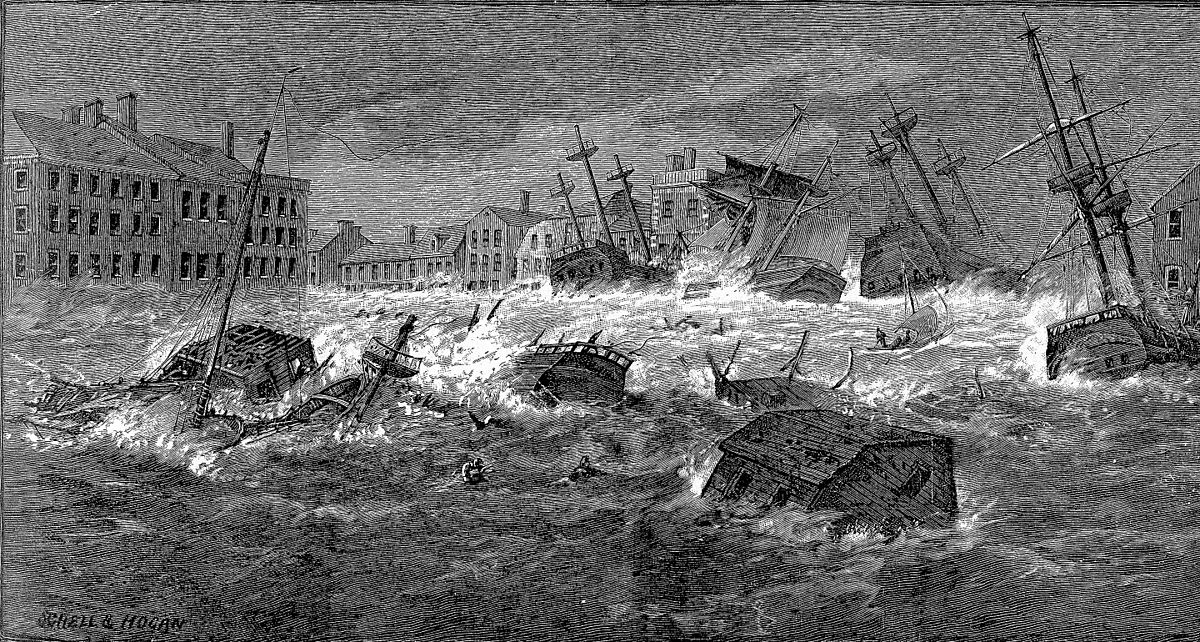

From a painting in the possession of the Rhode Island Historical Society showing downtown Providence during the Great Gale of 1815 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

This excerpt is from Arthur A. Ross’s history of Rhode Island, regarding the Great Gale of 1815’s impact on Newport:

The 23rd of September, 1815, is rendered memorable by a most awful and destructive storm, which swept away and laid prostrate, almost everything in its course. The Newport Mercury says, “The gale commenced early in the morning, at N. E., and continued increasing in violence, the wind varying from N. E. to S. E. and, S. W., until about 11 a.m., when it began to abate, and about 1 p.m., the danger from the wind and tide was over.” At Newport, the tide rose three feet and a half higher than it had ever been known before.

Two dwelling houses and nine stores and workshops on the Long Wharf, were swept away by the violence of the wind and waves; and those that withstood the power of this desolating scourge were rendered almost untenable by the vessels, lumber, &c., driving against them. Several of the stores carried away, contained a considerable amount of property, nearly the whole of which was lost.

In one of the houses carried away from the Long Wharf, five persons perished. The wharves on the Point, with most of the stores on them, were carried away. The wharves also in other parts of the town, with the stores on them, sustained considerable injury, and everything moveable on the wharves was swept away. In some of the stores, the water was four feet deep. A large three story store, containing hemp, flour, etc., was lifted from its foundation and floated into the harbor. The steeples of the first and second Congregational Churches were partly blown down, and the roofs of the Episcopal and first Congregational Churches were partly carried away.

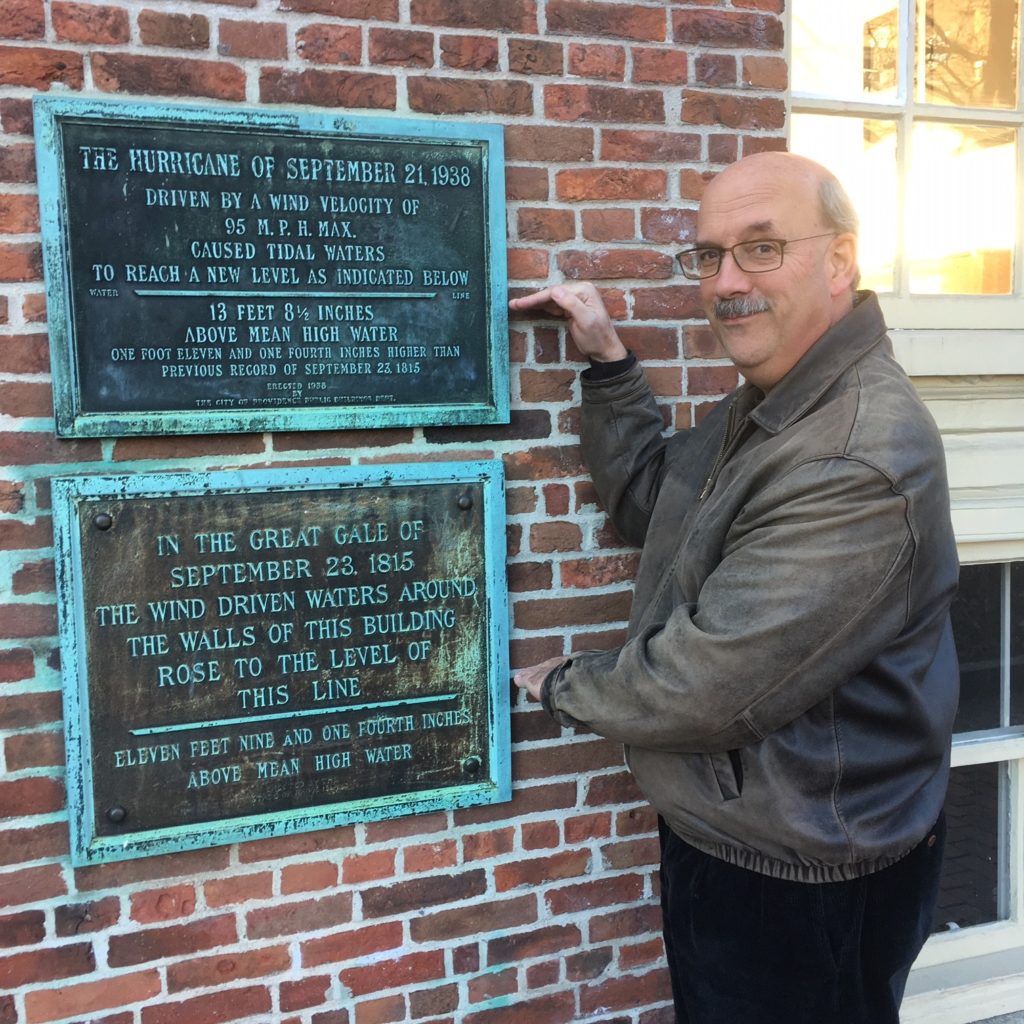

The author pointing to the water levels of the 1815 and 1938 hurricanes in two plaques at the Old Market House (built in 1775) in downtown Providence (next to the RISD Museum at 20 North Main Street, at the bottom of College Hill off College Street and the Canal Walk) (Margaret McBurney)

After the storm, it was found that the outside of windows, in the houses of this town, were covered with a fine salt, conveyed from the ocean through the air. This was also noticed for many miles inland, after the gale.

The shipping in the harbor were driven from their anchorage, and went ashore. Some lying side of wharves were lifted on them by the violence of the wind and tide, and left. Four sloops were lifted on the Long Wharf, and a sloop loaded with wood, went over the wharf into the cove.

The bottom plaque reads: In the Great Gale of September 23, 1815 the wind driven waters around the walls of this building rose to the level of this line, Eleven feet and one fourth inches above mean high water (Margaret McBurney)

This excerpt is from Arthur A. Ross’s history of Rhode Island, on the Great Gale of 1815’s impact on Tiverton and Point Judith:

The stone bridge, connecting [Aquidneck] Island with Tiverton on the main, was greatly injured and rendered wholly impassable. The draw and toll-house were carried away ; a new channel about three hundred feet wide, was made at the west end of the bridge, and where the toll-house had stood, the water was thirty. feet deep at low tide.

The light-house on Point Judith was swept away, with several other houses, in its vicinity. The Rhode Island Republican, says, “So great and general has been the devastation of property, that it is found impossible to give a correct account of the extent of damage.”

Bristol, Warren, Wickford, and East Greenwich also suffered great damage, in vessels and buildings.

This description of the Great Gale of 1815’s impact on Providence is from Welcome Greene’s history of Providence.

After a spring and summer of unexampled activity and prosperity, on the twenty-second day of September, an ordinary “line storm” seemed to have commenced. The wind was northeast and the usual amount of rain fell, and the townsmen went to bed anticipating the usual results. In the night the force of the wind increased. On the morning of the 23rd the wind changed to the east and blew with increased force. At about 9 a.m., it veered to east-southeast, and at 10 a.m., or before, to southeast, and blew a hurricane for nearly two hours.

Before 12 noon the wind had changed to the southwest, had calmed down, and the sun was shining brightly on the ruin and devastation those two short hours had wrought. The water had stood twelve feet higher than the spring tide-mark. It had extended from well up towards Benefit Street on the east side nearly to Aborn Street on the west. With the first burst of the hurricane the East India ship “Ganges,” belonging to Brown & Ives, of over five hundred and twenty tons burthen, and the largest in the harbor, had been forced from her moorings and hurtled against the Weybosset Bridge. Without a pause she smashed through the bridge, swinging her bowsprit into, and wrecking the upper story of the Washington Insurance building, as an angry elephant with his tusks destroys an enemy without stopping in mad career, and sped onwards till she reached the firm land at the head of the cove where she ended her career forever. Through the gap which she made poured other craft and wreck stuff till the shores of Smith’s Hill and the Moshassuck River were strewed with the wrecks of three ships, nine brigs, seven schooners, and fifteen sloops, besides houses, lumber, casks, and every imaginable sort of material that the angry flood had raised from the shores below and flung to the end of its reach. The succeeding vessels passing through the breach in the bridge had, by striking against its sides, widened it till no bridge was left. Nearly every vessel in the harbor had gone that way, and one sloop was carried into the limits of North Providence. All the vessels in the harbor, save two, had been driven from their moorings. As the waters abated—almost as rapidly as they rose—a large sloop was seen reposing in Eddy Street, between Weybosset and Westminster streets, against a three-story brick house, her mast showing proudly above it.

A plaque at the Rhode Island Hospital Trust Company building, built in 1919, at 15 Westminster Street in downtown Providence. The building is now a dorm for RISD (Margaret McBurney)

To the south of the bridge, the wharves, “on which had been stored the riches of every clime,” exhibited a most sad and repulsive aspect. “Scarcely a vestige remained of the stores, many of them very spacious, which had crowded the wharves bordering on Weybosset Street but two short hours before. Most of those on the east side from the south of the Market House clear round to India Point, suffered the same fate.” The wharves themselves were washed away, wrecked, and in many places utterly destroyed. Many of the streets in the lower part of the town were “almost barricaded” by an accumulation of lumber, scows, boats, etc., and as soon as the waters receded were crowded by anxious sufferers desirous of identifying and saving any of their property that had escaped destruction. Many dwellings were carried away from Eddy’s Point, while from other homes every article of furniture, clothing, and provision was lost.

The Second Baptist Meeting-house succumbed and went to pieces under the combined force of the wind and the waves, while the tall spire of the First Baptist Church wavered and bent to the blast, but it fell not. The streets in the upper parts of the town were strewn with the ruins of chimneys, trees, fences, and houses. At India Point houses and wharves were destroyed. The Washington Bridge was floated from its piers and destroyed, while the east end of the Central (Red) Bridge, suffered the same fate. Five hundred buildings were destroyed in this storm. It was “short, sharp, and decisive.” Never before, and it is to be hoped, never again will two hours witness an equal destruction in Providence.

The plaque at the Rhode Island Hospital Trust Company building reads: Height of Water in the Great Gale of September 23, 1815

Fortunately the loss of life was small, but two men, David Butler and Reuben Winslow, having perished, both at India Point. The pecuniary loss was estimated at the time at one and a half million dollars, which was about one-fourth of the total valuation of the town. This loss fell on the most enterprising and active members of the community.

The following excerpt is from J. R. Cole’s History of Washington and Kent Counties regarding the Great Gale’s impact on Narragansett and South Kingstown:

On the 23d day of September, 1816, a most terrific storm, accompanied with thunder and lightning, visited the coast of New England and spread desolation and dismay in every direction. In a southeasterly direction from South Kingstown, a confused mass of bright copper-colored clouds was seen, which dazzled the sight almost as much as the sun would, shining with its full effulgence. A mass of clouds arose from the horizon and after assuming the arch-like proportions of the rainbow, was driven with frightful rapidity toward the zenith, whilst upon either side were broken clouds that kept up a kind of vibrating and trembling motion that it is difficult to describe.

It was generally supposed that the storm was caused by a submarine volcanic eruption. This opinion was somewhat confirmed by the statement of the captain and crew of a vessel on her way from the Bermuda’s to Boston, who positively stated that, when about one hundred miles distant from Point Judith in a southeasterly direction, they saw a dense smoke arise from the ocean some miles in-shore, followed by a blaze and fire which appeared to extend over a space of a quarter of a mile. A violent southeast wind arose and continued to increase until it became a frightful hurricane.

This plaque at the Bannigan Building, built in 1896, at 10 Weybosset Street in downtown Providence, shows the water lines for the 1938 and 1954 hurricanes, both of which are higher than the water line for the Great Gale of 1815 (Margaret McBurney)

It was different from any gale ever before witnessed. The wind would blow in one direction for fifteen or twenty minutes and then it would lull for a moment and again resume its former direction with increased velocity. All buildings that had not substantial frames were blown down and the materials scattered in every direction; many others were unroofed, and the tunnels of the chimneys were swept away. Trees of all descriptions were either broken down or uprooted, and even the white oak, which is called the “monarch of the forest,” was prostrated to the ground. Fences, and in some cases stone walls, were no protection to corn fields, for they were blown down and the cattle had free range after they had got over their fright. Stacks of fodder were blown over and the contents scattered all over the meadows. The spray was driven twenty miles from the sea, and was recognized by the fruit which had a salt taste. The waves of the sea rose to a frightful height, and broke over Little Neck Beach and washed the sand hills in every direction. Before the gale a range of sand hills extended nearly the whole length of the beach, with intervening spaces which were partly covered with a rank growth of beach grass and a few scattering bunches of bayberry bushes, which afforded shelter for many small birds who deposited their eggs there during the. summer season and reared their young birds.

The middle bridge over the Pettaquamscutt River was swept away, as the water extended from the foot of the hill on the Dyer farm to a considerable distance up the pasturage, beyond the first wall east of the bridge.

Two families occupied a house which stood at the northeastern extremity of Little Neck Beach, and some members of each family were drowned, for the house was swept away by the flood. James. Phillips, the father of one of the families (a white. man), after the water had ascended some feet above the floor, laid hold on a chest and floated a mile up the river and cove and landed alive on the Hannah Hill meadow. Jesse Weeden (a colored man) was last seen alive on the top of the house hanging to the chimney, but was at length carried away and found dead upon the farm of Mr. Nichols. William Short, a lad ten years of age, was found on the Samuel Helme lot adjoining the homestead of Stephen Caswell, and two colored children were also found there. These three children were buried in the evening in the orchard of the Dyer farm, then owned by John J. Watson.

Captain John A. Saunders was building his first vessel on the training lot (as it was called) at this time, but she was not carried away, for he had blocked her up very high in order to square her bottom; but his temporary workshop was thrown down and tools scattered all around.

The water rose very high at New York and at all the intervening places between there and Boston. The most furious work of the hurricane was on the coast between Cape Cod and New. London. Several vessels were wrecked and quite a number of seamen were drowned.

When the storm commenced six men on Point Judith, whose names were William Knowles, and his son William, Joseph Hawkins, Jabez Allen and two colored boys named Joseph and Peter Case, went to the beach to secure a boat, but becoming frightened by an enormous wave (which was thought. to be forty feet high when it broke by those who saw it), took refuge in an ox-cart, but were swept away and drowned. The bodies of all of these men were found when the waters subsided, with the exception of William Knowles’s son, whose body was found twenty-one days afterward on Ram Island by Jeremiah W. Whalley, who in company with his cousin Ezekiel was on the island, gunning. William Knowles’s son, without doubt, landed on the island alive, and had crawled up some little distance out of reach of the tide, but was so much exhausted that he died there.

[Banner image: From a painting showing downtown Providence during the Great Gale of 1815 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]

Bibliography:

Arthur A. Ross. A Discourse, Embracing the Civil and Religious History of Rhode-Island (Providence, RI: H.H. Brown, 1838).

- R. Cole. History of Washington and Kent Counties (New York, NY: W. W. Preston & Co., 1889).

Welcome Arnold Greene. The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years: An Historical Review of the Foundation, Rise and Progress of the City of Providence (Providence, RI: J.A. and R.A. Reid, 1886).