[Note from the Author: Written in 1999 as an entry in The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America, ed. Michael Glazier (Notre Dame, 1999), 803-08, this essay was an abridgement and update of my 1986 booklet in the Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. This version appeared my Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection, Public Addresses and Essays (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2002), and has been slightly edited for length.]

The Protestant Pioneers

The Irish presence in Rhode Island dates from the mid-seventeenth century. Our knowledge of this Irish vanguard stems from the researches of several Irish American genealogists and apologists, such as Rhode Island’s Thomas Hamilton Murray, who scoured the records of the American colonies to establish a long Irish American lineage and thus overcome the charge of “foreignness” hurled at the nineteenth-century Irish and their Catholic Church. Ironically, most of these early Irish Rhode Islanders were Protestants — mainly Baptists, Quakers, Presbyterians, or Anglicans — and those few with Catholic antecedents soon lost their religious affiliation for lack of Catholic clergy within the colony. Among the handful of seventeenth-century Irish Rhode Islanders were Nicholas Power, an original Providence settler and his early descendants; Charles McCarthy, an original proprietor of (East) Greenwich in 1677; and Edward Larkin of Newport and Westerly, who served briefly in the colonial legislature.

In the early eighteenth century the colony’s most notable Irishmen were clergymen or schoolmasters. Among the former was Derry-born Reverend James MacSparran (1680-1757), for thirty-seven years the distinguished rector of St. Paul’s Church (Wickford), which served the spiritual needs of South County Anglicans. MacSparran, who tutored President Thomas Clap of Yale, gained renown by publishing America Dissected (Dublin, 1753), a collection of his letters to friends in Ireland, which proved for its British audience a valuable source of information on the American colonies. Another even more illustrious Irish scholar and clergyman was George Berkeley, the Anglican essayist and philosopher, who stayed at Whitehall Farm in present-day Middletown during his eventful sojourn in America from 1729 to 1731. After the failure of his cherished but impractical project of establishing an Anglican college in Bermuda, Berkeley returned to Ireland, where he was rewarded with the bishopric of Cloyne.

Notable Irish tutors (of whom there were a good number in relation to the small Irish population) included Stephen Jackson (1700-1765), who left Kilkenny and settled in Providence. This teacher and prosperous farmer had a son, Richard, who became president of the Providence-Washington Insurance Company (1800-1838) and a four-term congressman, and a grandson, Charles, a prominent industrialist who served as governor in 1845-46 after campaigning on a platform calling for the liberation of imprisoned reformer Thomas Wilson Dorr.

Other Irish schoolmasters were John Dorrance (1747-1813), a Providence civic leader, and the Reverend James “Paddy” Wilson of Limerick, first a teacher and then the colorful pastor of Providence’s Beneficent (“Roundtop”) Congregational Church. James Manning, first president of the College of Rhode Island (now Brown University) and the son of a New Jersey farmer, was probably of Irish descent. Though a Baptist in religion, Manning graduated from the College of New Jersey (Princeton), then a citadel of Irish Presbyterianism. Despite the fact that Manning’s Celtic origins are in doubt, it is certain that Protestants in Ireland financed much of the initial endowment for his College of Rhode Island.

Colonial Rhode Island’s most famous Irish craftsman was Kingston silversmith Samuel Casey, whose pieces are displayed today at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Its most renowned business family (Irish or otherwise) were the Brown brothers of Providence—James, Nicholas, Joseph, John, and Moses. The Browns’ mother, Hope Power, was the daughter of Nicholas Power III (1673-1734), a native of Providence who served in the Rhode Island General Assembly and as a colonel in the state militia. Colonel Power’s oldest daughter, Mary, was the mother of Nicholas Cooke, the state’s Revolutionary War governor (1775-78). In view of the sparseness of their numbers (one genealogist counted only 166 Irish surnames in the pre-1776 colonial records), the impact of the Irish on the English colony of Rhode Island was considerable.

During the American Revolution nearly three hundred Irish names appeared on Rhode Island’s military and naval rolls, and the American commander in New England’s largest military engagement, the Battle of Rhode Island, was General John Sullivan of New Hampshire, whose parents had migrated from Ireland in the 1720s. When Rochambeau’’ French army came to Newport as allies of the American cause in 1780, many of its soldiers were Irish nationals, particularly those men from Colonel Arthur Dillon’s regiment who served in Lauzun’s Legion.

A strong journalistic supporter of the Revolutionary cause was John Carter (1745-1814), the son of an Irish naval officer killed in the service of the Crown. Carter came to Providence as a journeyman printer from Philadelphia, where he had been apprenticed to Benjamin Franklin. From 1767 until 1814 he molded public opinion in Providence as the editor of the Providence Gazette. A major supporter of the ratification of the federal Constitution, Carter also served as Providence postmaster from 1772 to 1792. His daughter Ann (1769-98) married Nicholas Brown, Jr. (son of the famous Providence merchant), the great benefactor of Brown University. The present-day Brown family is descended from their only child, John Carter Brown.

Whereas John Carter was the child of an Irish naval officer, two notable Rhode Island commodores of the early national period were sons of an Irish immigrant mother. Newport’s Oliver Hazard Perry (1785-1819), hero of the decisive Battle of Lake Erie (1813), and Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858), who opened Japan to Western trade and influence in the 1850s, were the children of Sarah Wallace (Alexander) Perry, a native of Newry in County Down, and mariner Christopher Perry of South Kingstown, who met Sarah when he was confined to a British internment camp in Kinsale, Ireland, as a Revolutionary War prisoner (he had been part of the crew of an American privateer captured by a British ship). After the conflict, Perry sailed back to Ireland to bring Sarah to America. Another notable person of Protestant Irish ancestry was Governor John Brown Francis, who served as governor from 1833 to 1838 and in the U.S. Senate from 1844 to 1845.

The Catholic Pioneers

The first significant migration of Catholic Irish to North America began in the aftermath of the War of 1812, and Rhode Island partook of this influx. During the three decades between 1815 and 1845, a million Irishmen, most of whom were Roman Catholics, came to North America. Perhaps five thousand of these settled in Rhode Island.

The overwhelming majority of Irish migrants to Rhode Island became urban dwellers despite their rural background. They entered this unfamiliar milieu because they needed immediate employment, which Rhode Island’s burgeoning economy provided, and because they lacked the funds to continue onward to frontier areas. The federal census of 1850, the first national survey to record the nativity of the population, revealed that Rhode Island had 23,111 foreign-born out of a total population of 147,545. At this point the natives of Ireland totaled 15,944, or 69 percent of the foreign-born. By the time of the first state census in 1865, the foreign-born population had climbed to 39,703; of this figure the Irish-born accounted for 27,030, or 68 percent. By the federal count of 1870, there were 31,534 of Irish birth, and Providence ranked sixth among the cities of the nation in its number of Irish-born residents.

By 1875—sixty years after the onset of their immigration—the Catholic Irish had established settlements and churches in all the urban and industrial areas of the state, including Newport (especially the lower Thames Street neighborhood), Providence (mainly in Fox Point, the North End, Smith Hill, Olneyville, Manton, Wanskuck, and South Providence), Pawtucket, Woonsocket, the mill villages of Lincoln and Cumberland (including Central Falls, Valley Falls, Lonsdale, and Ashton), Harrisville, Pascoag, Greenville, Georgiaville, Cranston (especially Arlington and the Print Works district), the Pawtuxet Valley (particularly the villages of Crompton, Riverpoint, and Phenix), East Greenwich, Wakefield, Westerly, Warren, and Bristol. Aside from the English, no other Rhode Island ethnic group dispersed so widely.

Of the thousands of Irish who flocked to the state in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, many found their circumstances bleak. Depressed to the status of paupers by the conditions of their flight from Ireland, driven into debilitating slums or drab mill villages by their position as unskilled laborers, and isolated intellectually by their cultural background and physical segregation, these Irish saw insuperable social, economic, and religious barriers between themselves and the so-called “Yankees.”

On the eve of the Civil War, the Irish were the substratum of Rhode Island society. Spurned as lower-class menials, politically impotent, and discriminated against as Catholics (“No Irish Need Apply”), they were caught in a web of poverty and social alienation from which they would not escape until new immigrants came to take their place. Even politics, the traditional road of the Irish to power and prestige, was blocked by formidable constitutional obstacles such as the real estate requirement for voting, imposed by Rhode Island’s basic law upon those of foreign birth.

During the nineteenth century, Irish immigration and the growth of the Catholic Church were closely intertwined. The first tiny Irish Catholic communities were at the Portsmouth coal mines and in the Fox Point section of Providence near that town’s bustling harbor. French priests from Boston began to visit both areas during the second decade of the century. The Providence Irish secured the use of a building on Sheldon Street as the state’s first Catholic church in 1813, but the structure was destroyed by the Great Gale of 1815.

A more significant influx of Irish occurred in the mid-1820s, prompting Bishop Benedict Fenwick of Boston to dispatch Father Robert Woodley to Newport in 1828 as Rhode Island’s first resident priest. There, in April 1828, the young cleric founded St. Mary’s, the state’s oldest parish. In 1829 the busy Woodley—whose mission territory included the states of Rhode Island and Connecticut in their entirety, plus southeastern Massachusetts —built the state’s first Catholic church specifically constructed for that purpose at St. Mary’s, Pawtucket.

When Woodley came to Rhode Island to establish a Catholic presence, Rhode Island’s Roman Catholics numbered about 600 out of a total state population of 97,000, a mere six-tenths of 1 percent. The 600 faithful served by Woodley in 1828 were concentrated in Newport, where they worked as laborers on Fort Adams; in Portsmouth, where they were employed as miners at the coal pits; and in Providence, Cranston, Pawtucket, and Woonsocket, where they served the needs of the growing factory system or were employed in such public works projects as the construction of the Blackstone Canal. Nearly all of them were Irish. In the 1830s, as the railroad came to Rhode Island, this Irish migration continued, and in the 1840s and 1850s, in the wake of Ireland’s disastrous famine, it reached impressive proportions. By 1865 three out of every eight Rhode Islanders were of Irish stock, the state’s Irish Catholic community numbered nearly 50,000, and pioneer missionary priests like the Reverend James Fitton had established twenty widely scattered parishes. The energetic and seemingly ubiquitous Fitton, a founder of Holy Cross College (1843), was a driving force in the development of Rhode Island Catholicism, serving in every major area of Irish settlement.

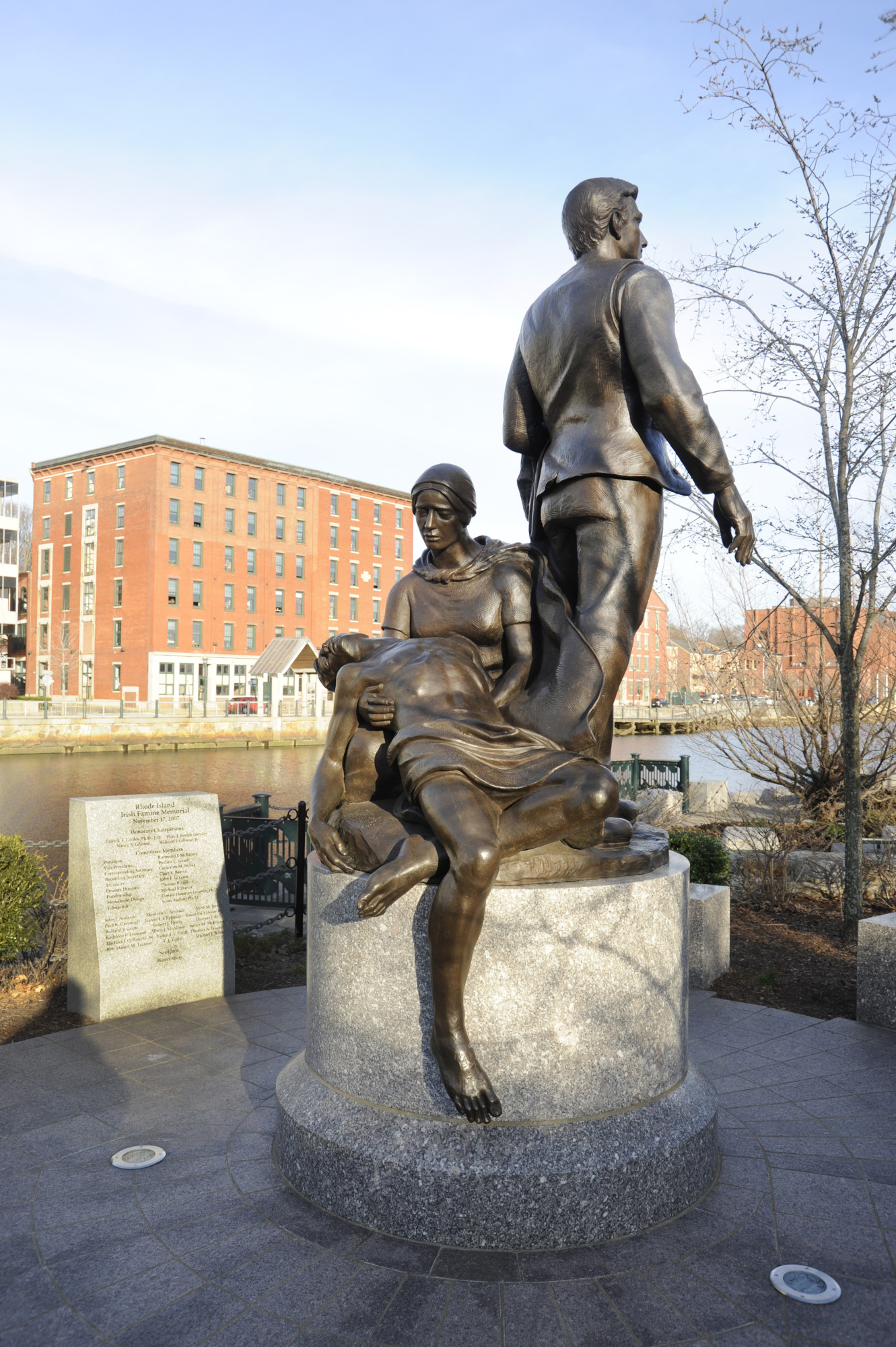

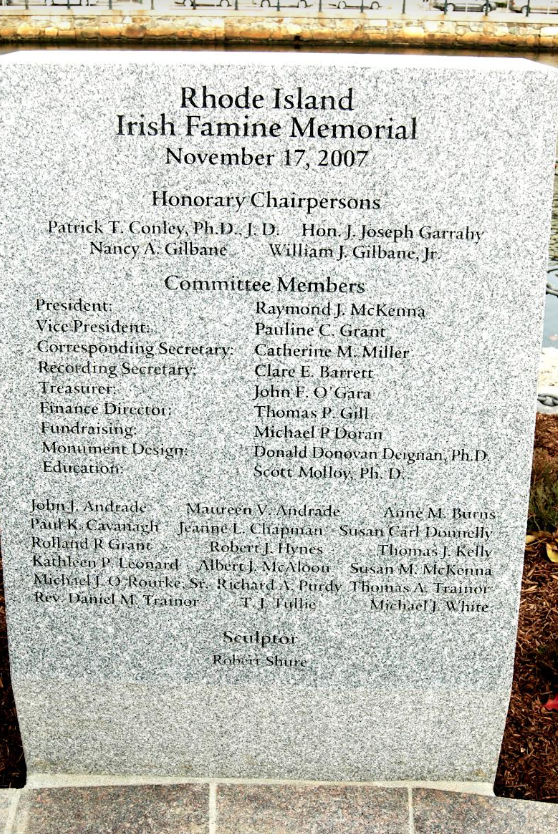

View of the grounds at Riverwalk, at the head of navigation, of the Rhode Island Irish Famine Memorial and statue (Richard McCaffrey)

To accommodate the Catholic Irish influx of the mid-nineteenth century, the Diocese of Boston was subdivided and the Diocese of Hartford created in 1844. This new administrative entity included the states of Connecticut and Rhode Island. Its first bishop, William Tyler, was a Yankee convert from Protestantism. Although the see city of his new diocese was Hartford, Tyler decided to govern from Providence, which was a more prosperous community with a larger Catholic population.

The decade of the 1840s saw several important developments affecting the Irish Catholic community. One was the famous Dorr Rebellion, which occurred between 1841 and 1843 over an attempt to broaden democracy in Rhode Island and replace the antiquated royal charter of 1663 with a written state constitution. The opponents of political reformer Thomas Dorr were partly motivated by anti-Catholic prejudice and political nativism, themes that have often been ignored or downplayed in discussions of this colorful but crucial episode in the state’s history. Over the objections of Dorr, Rhode Island’s state constitution of 1843 established a real estate requirement for foreign-born voters that was primarily designed to discriminate against Irish Catholic immigrants.

Another event of importance was the John Gordon murder trial—the Sacco-Vanzetti case of the nineteenth century. This 1844 travesty of justice, which on the basis of circumstantial evidence resulted in the hanging of a young Irish Catholic immigrant for the killing of prominent industrialist Amasa Sprague, caused such misgiving that it contributed to the abolition of the death penalty in Rhode Island eight years later.

In 1850 William Tyler was succeeded as bishop of Hartford by Irish-born Bernard O’Reilly, called “Paddy the Priest” by some native Rhode Islanders. In 1851 this bold and strong-willed bishop brought Mother Mary Frances Xavier Warde and the predominantly Irish Sisters of Mercy to Providence, where they immediately founded a school for girls, St. Xavier’s Academy, the first Catholic secondary school in the state. Four years later, during the height of the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing movement, O’Reilly personally defended the Mercy nuns from an anti-Catholic mob that had congregated at St. Xavier’s Convent to “free” a young girl who had allegedly been confined therein. Returning from a clerical recruiting trip to Europe in 1856, O’Reilly perished at sea when his ship was lost in a North Atlantic storm.

The last bishop of Hartford to preside over Rhode Island Catholicism was Francis Patrick McFarland, whose episcopacy coincided with the Civil War and Reconstruction years. This gentle and scholarly prelate’s tenure was marked by the emergence of a Catholic presence in the social and political affairs of Rhode Island. McFarland’s energy and learning built the first bridges to the non-Catholic community of the state, resulting in a lessening of the ethnocultural antagonisms that had dominated the 1840s and 1850s.

The Civil War was a testing ground that also helped to mollify native fears of Irish Catholics. Animated by a desire to preserve the Union and thereby prove their Americanism, Irish immigrants and their sons fought side by side with Yankee boys. Two members of the local Irish community—John Corcoran and James Welsh—were recipients of the newly created Congressional Medal of Honor for their wartime heroism.

The other salient fact of this period was the role of the lowly Irish immigrants in building the Diocese of Providence. During the years prior to 1872, almost the only influences upon Rhode Island Catholicism were those distinctive Irish traits that gave the local Catholic community a unified religious outlook and produced what was in reality an Irish national church. The creation of the Diocese of Providence (with Irish-born Thomas F. Hendricken its first bishop) was the Irish immigrants’ first notable achievement in Rhode Island.

Irish on the Rise, 1880-1921

During the last third of the nineteenth century, the era of America’s Industrial Revolution, the Irish of Rhode Island made a slow yet significant climb up the socioeconomic ladder as new immigrants from French Canada, eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean took their place on the bottom rungs. Political advancement also became less difficult as more native-born Irish reached voting age. Whereas the 1865 state census revealed that “only one in twelve or thirteen of the foreign-born of adult age was a voter,” economic advancement for the Irish immigrant and native birth for his male children combined by the 1880s to make the real estate requirement for voting and officeholding much less restrictive.

According to the census of 1885, the state had 92,700 citizens with at least one parent of Irish birth, but for the first time more than half of these (50,313) were native-born. When these foreign-stock Irish (immigrants or their children) were added to second-and third-generation Irish Americans and Irish migrants from England, Scotland, and Canada, the total number must have approximated 125,000 in a general Rhode Island population of 304,000. This ratio was the relative high point of the Irish numerical presence in the state.

Numbers plus native birth equaled political clout. Leading the Irish political advance was Charles E. Gorman (1844-1917), Boston-born of an Irish father and a Yankee mother. An outspoken advocate of equal rights and suffrage reform, Democrat Gorman successively became the first Irish Catholic member of the Rhode Island bar (1865), state legislator (1870), Providence city councilman (1875), Speaker of the House (1887), and U.S. attorney (1893). His younger colleague, attorney Edwin Daniel McGuinness (1856-1901), became the first Irish Catholic general officer, winning election as secretary of state in 1887. In 1896 Democrat McGuinness also became Providence’s first Irish Catholic mayor.

The city’s most notable chief executive of this or any era was Thomas Doyle, of Irish Protestant stock, whose eighteen years of service between 1864 and 1886 constituted an unparalleled era for Providence’s growth and development. A contemporary of Doyle’s, Dublin-born Thomas Davis, was a prominent businessman who served one term (1853-55) in the Congress of the United States. Although Davis was a Protestant, he was an outspoken foe of nativism.

In the state’s other cities, where the urban-dwelling Irish had also congregated, similar political breakthroughs occurred. In Pawtucket, Irish Catholic Hugh J. Carroll gained the mayoralty in 1890, followed by coreligionists Patrick J. Boyle in Newport (1895), Thomas McNally in Central Falls (1905), and Edward Sullivan in Cranston (1910), the first mayor of that city.

Attorney James H. Higgins, who had succeeded the colorful and dynamic John J. Fitzgerald as mayor of Pawtucket in 1903, won election in 1906 and again in 1907 as Rhode Island’s first Irish Catholic governor. He had been preceded by reformer Dr. Lucius F. C. Garvin, a Protestant of Irish ancestry and a native of Tennessee who served as governor of Rhode Island from 1903 to 1905.

Galway-born Democrat George O’Shaunessy (1868-1934) became another local Irish Catholic pathbreaker, securing election four times to the U.S. House of Representatives (1911-19). He was followed to Washington two years later by Irish Republican Ambrose Kennedy of Woonsocket, who served five terms in the House. In 1913, with the victory of Joseph Gainer, the Irish began their unbroken sixty-two-year grip on the Providence mayoralty, and by that time they were firmly in control of the organizational structure of the Democratic party.

The Irish economic rise, though less spectacular, had some rags-to-riches scenarios. The most notable climb was made by Joseph Banigan (1839-98), Rhode Island’s first Irish Catholic millionaire. The Irish-born son of parents who migrated to Rhode Island from Scotland in 1849, Banigan got in on the ground floor of the emerging rubber-goods industry and improved Charles Goodyear’s process for the vulcanization of rubber. By 1889 he opened the Alice Mill in Woonsocket, then the largest rubber-shoe factory in the world. Three years later Banigan helped form the massive U.S. Rubber Company and became its president (1893-96). In 1898 he financed the construction of Providence’s first ‘skyscraper,” the ten-story Banigan Building, which still stands today.

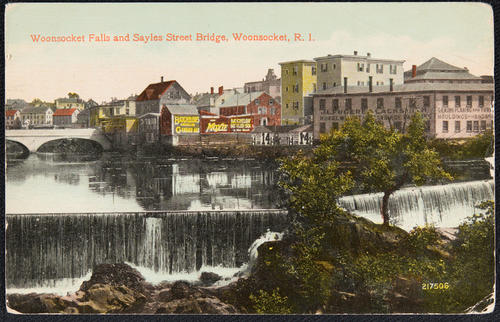

Statue of an Irish immigrant family. The man seems to look forward to immigrating to Rhode Island for a better life (Richard McCaffrey)

By the end of the century Irish-born William and Thomas Gilbane had directed their firm (established in 1873) to the forefront among local building contractors, and James Hanley (1841-1912), another Irish immigrant, had become the region’s most prominent brewer. Though such Horatio Alger stories were not common, Irish American small businessmen, lawyers, and physicians were becoming increasingly so in the early years of this century. Especially notable was Dr. John William Keefe, a founder of St. Joseph Hospital, a World War I surgeon, president of the Rhode Island Medical Society (1913-14), president of the American Association of Obstetricians, Gynecologists, and Abdominal Surgeons (1916-17), and founder of a surgical center in Providence.

In the blue-collar field, Irish Americans made great strides in the building trades, acquiring skills as masons, carpenters, plumbers, steamfitters, painters, plasterers, electricians, and ironworkers. Railroad, streetcar, and public-utility employment, professional police work, and firefighting also had strong appeal.

As Irish American labor leaders affiliated with the Knights of Labor or the AF of L led the fight for the eight-hour day, Americans used their newly acquired leisure to partake of such popular spectator sports as professional baseball. The new national pastime produced a number of local Irish American luminaries, including “Orator Jim” O’Rourke, batting star of the national champion Providence Grays, and Hugh Duffy of Cranston, whose 1894 batting average of .438 with Boston of the National League is still the unapproachable major league baseball record. Both O’Rourke and Duffy are enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

A more genteel spectator activity of great popularity was vaudeville. Here also the Rhode Island Irish community produced performers of national stature, the most magnetic of whom was George M. Cohan. Born in the Fox Point section of Providence on July 3, 1878, to variety performers Jerry and Nellie (Costigan) Cohan, George joined his sister Josie and their parents on stage well before he reached his teens. The four Cohans left the local circuit for Broadway during the 1890s. Cohan eventually became America’s most successful theatrical producer, and during his fifty-five years in show business he composed more than five hundred songs, including such patriotic airs as “Over There,” “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” and “Yankee Doodle Boy.”

In 1917 Bishop Matthew J. Harkins, the fourth and most productive in a line of seven Irish Catholic bishops of Providence spanning the years from 1850 to 1971, joined with a group of Irish professionals and businessmen and the Dominican Fathers of the Province of St. Joseph to found Providence College. The original purpose of the college—to provide higher education with a Christian perspective to aspiring young men from the local Catholic community—was proclaimed at the dedication mass offered at the doors of Harkins Hall in May 1919. A major participant in these exercises was Dr. Charles Carroll, Rhode Island’s most prominent public educator. The scholarly Carroll would eventually write the most authoritative multivolume history of the state, the first such work to give prominence to Rhode Island’s more recent immigrants.

By the time Providence College was founded, Rhode Island Irishmen had already achieved distinction for their cultural and literary attainments. In 1884 Alfred Thayer Mahan, descendant of an eighteenth-century Irish immigrant, began a productive tour of duty at Newport’s newly created Naval War College, where he served both as professor and president. In 1890 Mahan (1840-1914) published The Influence of Sea Power upon History, the most famous and influential of his numerous historical volumes advocating American expansion on strategic grounds.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, the local Irish were given an advance look at the literary efforts of several promising young Irish authors by a most unlikely source—the Providence Journal. For forty-five years (1839-84), while the paper had been under the malign influence of nativist and machine Republican Henry B. Anthony, Irish Catholics and Democratic politicians had been its twin enemies. This changed (at least temporarily) when Alfred M. Williams (1840-96) began his seven-year tenure as Journal editor in 1884. The most notable aspect of Williams’s career became his study and promotion of Irish literature. He wrote several works on the topic and published in the newly created Providence Sunday Journal the early efforts of several then-obscure Irish authors, including William Butler Yeats, Douglas Hyde, Katherine Tynan, and Mary Banim. Professor Horace Reynolds, in his booklet A Providence Episode in the Irish Literary Renaissance, calls these works “a record in miniature of the beginnings of a movement that is today recognized as one of the most distinctive in the stream of English letters.”

In January 1897 the American-Irish Historical Society was formed, largely through the efforts of Thomas Hamilton Murray, editor of the Woonsocket Evening Call and the Pawtucket Times, who became this national organization’s first secretary-general and the editor of its widely circulated historical journal. Murray wrote a number of well-researched articles on the early Rhode Island Irish for his journal and hosted several of the society’s national conventions. Many prominent Rhode Islanders of Irish ancestry (regardless of their religious affiliation) joined the organization, including Thomas Z. Lee of Providence, who succeeded Murray as secretary-general, and Father Austin Dowling of Providence, who wrote the first scholarly history of the Diocese of Providence in 1899 and later became archbishop of St. Paul, Minnesota.

By 1922, the year the Irish Free State was created, Rhode Island’s Irish had made major advances in all walks of life. No major political office had eluded their grasp, and they dominated the hierarchy of the state’s Democratic party, though that party was still the minority.