[Note from the Author: Written in 1999 as an entry in The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America, ed. Michael Glazier (Notre Dame, 1999), 803-08, this essay was an abridgement and update of my 1986 booklet in the Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. This version appeared my Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection, Public Addresses and Essays (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2002), and has been slightly edited for length. This is Part II of II.]

In the three generations from the early 1920s to 1999, Rhode Island’s Irish Americans achieved distinction and success commensurate with their rapidly increasing numbers. With two of every nine Rhode Islanders claiming Irish ancestry by the 1990 federal census, an essay of this limited scope can scarcely do justice to its subject.

The Irish Arrive in Politics, 1922-1999

During the two decades between world wars, the state experienced a turbulent political transformation from traditional Republican party dominance to rule by the Democrats. The Irish were the architects of that upheaval. By finally mastering the game of ethnic politics (much later than their counterparts elsewhere) and taking advantage of economic shifts, social changes, and cultural trends on both the state and national levels, Irish Democratic politicians weaned Franco-Americans, Italians, Jews, Poles, and blacks from their traditional Republican allegiance and ushered them into an Irish-led Democratic fold that dominated state government from 1940 through 1984.

The spearheads of this Irish political advance were a handful of youthful legislators who entered the General Assembly in the years following the outbreak of World War I. Foremost among them were William S. Flynn of South Providence, Holy Cross, and Georgetown Law School; Robert Emmet Quinn, a Brown- and Harvard-educated attorney from West Warwick and the nephew of Colonel Patrick Henry Quinn, who had carved the mill town of West Warwick from Warwick’s western sector in 1913; Francis B. Condon, a Georgetown Law School graduate from Central Falls; and Thomas Patrick McCoy, a Pawtucket streetcar conductor.

Of this bright, ambitious group, Flynn was the first to rise and the first to fall. Having won an upset victory in the 1922 gubernatorial race, he saw his administration made turbulent by zealous Democratic attempts to enact constitutional reforms, attempts that were countered by equally determined Republican moves to maintain the status quo. In 1924, after the adjournment of the infamous “stink-bomb legislature,” Flynn lost his bid to become Rhode Island’s first Irish American United States senator.

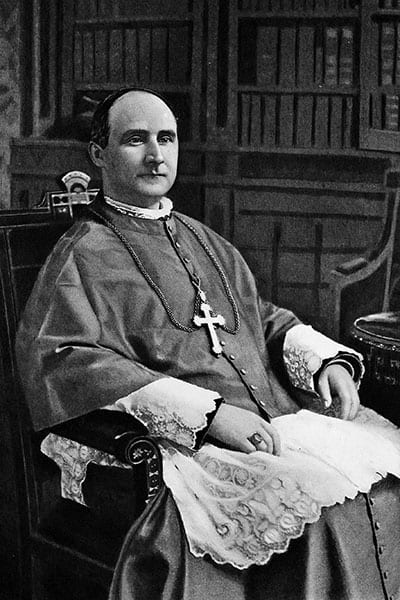

Harkins Hall at Providence College, circa 1940, named after Bishop Matthew Harkins (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Thomas P. (“Tom”) McCoy moved from the legislature to the city chairmanship and then to the mayoralty of Pawtucket (1936-45). Though his plans for statewide office were thwarted, he was a major strategist in the Bloodless Revolution of January 1935—that “first hurrah” whereby the Democratic party seized control of state government in a bold coup. McCoy also exerted a great impact on state policies and elections from his Pawtucket command post. There, with the aid of House Speaker Harry Curvin, he constructed Rhode Island’s best example of a genuine, smooth-functioning political machine.

Francis B. Condon, McCoy’s Blackstone Valley neighbor from Central Falls, operated on a more elevated plane. He moved in succession from the Rhode Island House (1921-26) to the Congress (1930-35) to the state Supreme Court (1935-65). For his last seven years on the bench, Condon served as chief justice, succeeding Edmund W. Flynn (William’s brother), who had assumed direction of the high court on January I, 1935, as a result of the Bloodless Revolution. Flynn’s twenty-two-year tenure has been the longest in Rhode Island’s history.

Of all those Irish political leaders of the post-World War I era, Robert Emmet Quinn was the most durable. Quinn rose from the state Senate (1923-25 and 1929-33), where he led the famous 1924 filibuster, to the lieutenant governorship (1933-37), where he presided over the Bloodless Revolution, to the governorship (1937-39), where he battled with Narragansett Park director Walter O’Hara in the ludicrous and nationally scandalous “Race Track War” of 1937, called by Life magazine “the War of the Wild Irish Roses.” Although that episode and a national recession cost “Battling Bob” reelection, he was later appointed to the Rhode Island Superior Court (1941-51) and then to the newly established U.S. Court of Military Appeals (1951-75), where he served as chief judge.

Cover of a book on Robert E. Quinn published by the Rhode Island Publications Society and available at its website (Rhode Island Publications Society)

One Rhode Island Celt who sought from the start to carve out his political career on the national level was Thomas Gardiner (“Tommy the Cork”) Corcoran (1900-81), a leading draftsman and lobbyist for much of the legislation now labeled Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Corcoran, a Pawtucket-born son of an Irish immigrant, attended Brown University where he was a football star, president of the debate club, class vice president, an accomplished pianist, a star of stage plays, and class valedictorian. Recommended by his Harvard Law School professor Felix Frankfurter, Corcoran joined the New Deal “Brain Trust” and drafted such landmark laws as those creating the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Housing Administration, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Fair Labor Standards Board. He often entertained Roosevelt with Irish ballads as well as drafting some of the president’s political speeches. Another local Irishman lured to the Potomac was John Fanning, a twenty-five-year member of the National Labor Relations Board, which he chaired from 1977 to 1981.

During the decades following 1935, when the Irish-led Democratic party solidified its hold on state government, a new wave of home-grown Irish American political leaders emerged. Most notable of these Roosevelt-era luminaries were J. Howard McGrath, John E. Fogarty, Dennis J. Roberts, William E. Powers, and Harry F. Curvin.

Curvin was the protégé and ally of McCoy. He represented Pawtucket in the state’s House from 1931 to 1964. During the last twenty-three years and 223 days of that long tenure, he presided (some say dictatorially) as Speaker. No one has ever approached Curvin’s longevity record as House leader.

William E. Powers of Central Falls overcame the handicap of blindness, the result of a childhood accident, to rank at the top of his Boston University Law School class. After five terms in the House (1939-49), Powers served nine years as attorney general before his elevation in January 1958 to the state Supreme Court. In 1973, having stepped down after fifteen distinguished years on the high-court bench, he reemerged to chair that year’s highly successful state constitutional convention.

Dennis J. Roberts, a noted high school athlete at LaSalle Academy, was perhaps the most powerful figure in state government during the decade following World War II. From 1941 to 1951 he served as mayor of Providence under that city’s first strong-mayor charter, and he presided as governor from 1951 to 1959.

John E. Fogarty was even more durable. This bricklayer-turned-politician went to Washington as congressman from Rhode Island’s Second District in January 1941. There he remained until his sudden death twenty-six years later. Fogarty’s many achievements in the area of health care legislation won him the national title of “Mr. Public Health,” but the man with the green bow tie was equally renowned as an unrelenting supporter of Irish unification.

Woonsocket-born J. Howard McGrath was undoubtedly the state’s most versatile politician. After spending the war years as Rhode Island’s governor, he was appointed U.S. solicitor general by his close political ally Harry S. Truman. In 1946 McGrath was elected to the U.S. Senate, the first Rhode Island Irish Catholic ever elected to that office. The following year Truman named him Democratic national chairman, and McGrath quickly proved his worth in the 1948 elections by overseeing Truman’s surprising upset of presidential hopeful Thomas E. Dewey. In the following year the ambitious Rhode Islander gave up his Senate seat to become U.S. attorney general. After resigning this post in 1952, he returned to private business and the successful practice of law.

In addition to this political “big five” of the past half century, passing mention, at least, should be accorded also to United States senator Jack Reed; U.S. congressmen Jeremiah O’Connell, James M. Connell, Robert O. Tiernan, Eddie Beard, and Patrick Kennedy (of the famous Kennedy clan); Supreme Court chief justices Thomas Roberts (brother of Governor Roberts), Thomas Fay, and Joseph R. Weisberger (whose mother was a Meighan); Lieutenant Governor, Acting Governor, and Superior Court justice John S. McKiernan; interim U.S. senator and federal District Court judge Edward L. Leahy; and four-term governor J. Joseph Garrahy. An impressive roster, certainly, even without all of those mayors, general officers, legislators, federal and state jurists, legislative leaders, and long-tenured civil servants who are simply too numerous to be included here.

In the annals of Irish achievement, the past two decades have been notable for the rise of women to the top of the political ladder. One such achiever worthy of special mention is Florence Kerins Murray of Newport, who became, successively, the first woman associate justice of the Superior Court (1956), that court’s first female presiding justice (1978), and the first woman to sit on the Rhode Island Supreme Court (1979).

The Irish Arrive in Many Fields, 1922-1999

From the 1920s until 1971, Irish Americans continued their dominance in the local hierarchy of the Catholic Church. William Hickey became coadjutor bishop of Providence in 1919, when Matthew Harkins was in declining health, and having ascended to the See of Providence in his own right on Harkins’s death in 1921, he presided until 1933. Hickey’s successor, Francis P. Keough (1934-47), was a popular bishop who made some important innovations, most notably the creation of the Catholic Youth Organization (1935), the establishment of Our Lady of Providence Seminary for the education of young men preparing for the priesthood (1941), and the founding of Salve Regina University in Newport (1947). A crusader against obscenity in movies and in print, Keough served as national chairman of the Bishops’ Committee of the National Organization for Decent Literature (Legion of Decency). After the departure of Keough to the archbishopric of the primal See of Baltimore in 1947, Russell J. McVinney (1948-71) assumed spiritual direction of the diocese—the only Rhode Island native to hold that post. The impressive material gains that the Church made during his episcopacy attested to McVinney’s administrative expertise. His tenure was a period in which Rhode Island Catholicism expanded its social role.

Many other able Irish clerics served as administrators in the Providence diocese or were raised here and then departed to assume positions of church leadership elsewhere. John Cardinal Dearden, archbishop of Detroit, was born and spent his boyhood in the Blackstone Valley, and Daniel P. Reilly of South Providence, a former diocesan chancellor, became bishop of Norwich, Connecticut, and then of Worcester, Massachusetts.

The Rhode Island Irish have been less conspicuously successful in the world of business and corporate finance. With the exception of the nationally ranked Gilbane Building Company (founded in 1873), which spearheaded the revitalization of downtown Providence and is currently the state’s largest private firm, there are no spectacular success stories, no Browns or Banigans, no Fortune 500 companies to the credit of Rhode Island’s modern Irish community. However, former pharmacist Thomas M. Ryan now serves as chairman, president, and CEO of Woonsocket-based CVS, Rhode Island’s largest Fortune 500 firm.

The Catholic Irish have not been well represented at the top echelon in the major white-collar businesses of insurance and banking, but there have been two notable exceptions: John J. Cummings, Jr., and his protégé J. Terrence Murray, who held in succession the top position at Fleet National Bank, once Rhode Island’s major financial institution and, under Murray’s leadership, one of America’s ten largest banks. A more local and more typically Irish business, the distribution of beer and liquor, gained wealth and prominence for Cumberland’s John McLaughlin and John E. Moran. In turn, they became civic leaders, philanthropists, and prominent Catholic laymen—pillars of their community and their Church.

In the field of letters, Rhode Island’s Irish American community produced two noteworthy novelists of Irish American life as well as a noted poet. In 1946 Edward McSorley, who lived for a time on Providence’s South Side, published Our Own Kind. This widely circulated Book-of- the-Month Club selection poignantly depicts the travails of the McDermotts, an Irish working-class family in St. Malachi’s (St. Michael’s) Parish. Its sequel, Young McDermott, appeared three years later. Even more famous and widely read than McSorley was Woonsocket’s Edwin O’Connor (1918-68). This product of LaSalle Academy had among his credits such Irish American literary classics as The Last Hurrah (1956), the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Edge of Sadness (1961), and All in the Family (1966). Galway Kinnell, a major American poet, has Rhode Island roots in Pawtucket. Among his many honors are a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

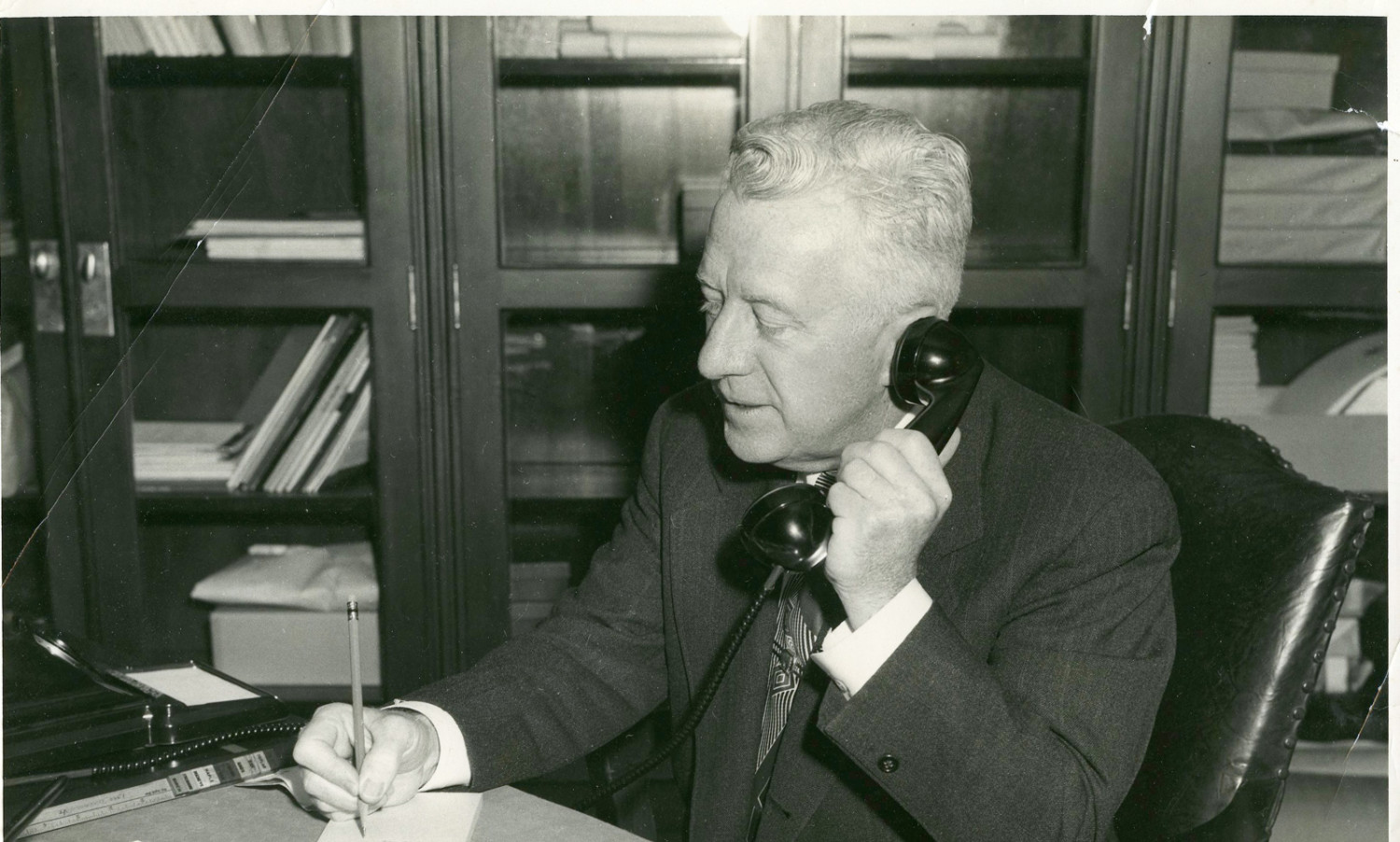

J. Howard McGrath speaking at an Armistice Day event on November 11, 1939 (Harry S. Truman Library & Museum)

In Irish American nonfiction, George W. Potter, a former editor at the Providence Journal, penned one of the best general histories of the early-nineteenth-century Irish migration—his popularly written and posthumously published To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America (1960). Another Providence Journal editor, John C. Quinn, went on to become one of America’s leading newspaper executives and a founder of USA Today.

Thomas N. Brown, who taught for six years at Portsmouth Priory, was the author of Irish-American Nationalism, 1870-1890 (1966), the standard account of Irish American reaction to the home rule movement led by Charles Stewart Parnell. More recently, Professors Robert W. Hayman, Matthew J. Smith, and Patrick T. Conley of Providence College have published books on nineteenth-century Rhode Island Catholicism emphasizing the impact of the Irish on Church growth.

In the modern period, the Rhode Island Irish community produced several nationally prominent entertainers, most notably Eddie Dowling of Woonsocket (1889-1976), a Pulitzer Prizewinning playwright, Broadway composer, and producer; jazz trumpeter Robert L. “Bobby” Hackett (1915-76) from Providence; Woonsocket’s famed soprano Eileen Farrell; Warwick’s James Woods, a noted Hollywood actor; and Cumberland’s Farrelly brothers, Peter and Bobby, who write and produce popular comedy films (including “Dumb and Dumber,” “There’s Something About Mary,” and “Outside Providence”).

Irish competitiveness and pugnacity have brought prominence to many in the annals of Rhode Island sports. In boxing, Leo Flynn achieved national prominence, serving as Jack Dempsey’s manager in the years following the Manassa Mauler’s loss of his heavyweight crown to fellow Irish American Gene Tunney. In football, another hard-hitting sport, the local Irish rooted for D. O. “Tuss” McLaughry, Brown’s most successful football coach and the mentor of the famed “Iron Men” of 1926, and for U.S. Navy ace pilot John A McIntyre, an All-American lineman at Notre Dame and a highly decorated war hero, who earned the Silver Star, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, and four Air Medals for his exploits in World War II and Korea.

But it was in baseball that Rhode Island’s Irish Americans made their greatest impact. O’Rourke and Duffy of an earlier era were succeeded in the Hall of Fame by Woonsocket-born Charles “Gabby” Hartnett. The oldest of fourteen children, Hartnett made his major league debut with the Chicago Cubs in 1922 and played with them for a nineteen-year span that included four World Series. Joe McCarthy, the great Yankee manager, labeled Hartnett “the best catcher of all time.”

Florence Murray, then a major in the Women’s Army Corps, ca. 1945. Signed, presumably to Harry S. Truman, “Affectionately Florence” (Harry S. Truman Library & Museum)

Also making their mark in the big leagues were the Cooney family of Cranston. James John Cooney, born in Cranston in 1865, was the patriarch of the clan. He had four ballplaying sons, and they in turn produced six grandsons in the same mold. Jimmy Cooney, Sr., played for three years as a shortstop with Cap Anson’s Cubs in the early 1890s. He then passed on the fundamentals of the game to his sons, two of whom —Jimmy Jr., known as “Scoops,” and John—also went on to the major leagues. Scoops Cooney won acclaim as one of the classiest-fielding shortstops of his era. In May 1927 he accomplished that extreme rarity in baseball, an unassisted triple play. Johnny Cooney played for twenty seasons in the major leagues with Boston and the Brooklyn Dodgers. An excellent outfielder, he led the National League twice in fielding and made only thirty-four errors during a career consisting of 1,172 games.

On the distaff side, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Murphy of Warren was a nationally prominent pioneer in women’s baseball. Indeed, she is credited with being the first woman to play the game professionally. Known as the “Queen of Baseball,” Murphy was also the first woman to play in the Negro Leagues. She played first base for the Cleveland Colored Giants during a game held at Rocky Point, Rhode Island.

In recent years basketball has held center stage among those sports played in Rhode Island. Providence College teams under Joseph P. McGee (also of Providence Steam Roller fame) and “General” Al McClellan won national recognition in the late 1920s and early 1930s, as did Frank W. Keaney’s fine squads at the University of Rhode Island in the 1940s. Keaney (who also coached four other sports at URI from 1920 to 1955) helped revolutionize basketball with his racehorse style of play and his “point-a-minute” teams that starred such renowned players as Ernie Calverley.

From the late 1950s through the 1970s, Providence College basketball again held the limelight. The Friars, under the successive tutelage of Joe Mullaney and Dave Gavitt, became a national basketball power featuring such luminaries as John Egan, Mike Reardon, Kevin Stacom, Fran Costello, Billy Donovan, and Providence’s own Joe Hassett, all of whom made it to the National Basketball League, and Ray Flynn, who became mayor of Boston and U.S. ambassador to the Vatican.

A lesser-known but even more successful (and more Irish) athletic program at Providence College has been cross-country. For a decade in the 1970s and early 1980s, Friar runners dominated New England long-distance events and were consistently among the best in the nation. This dominance was due primarily to a steady stream of Irish imports, some of whom took up permanent residence in Rhode Island. The most notable performer among this wave of talented Irish harriers was John Treacy, who won the 1984 Olympic silver medal for Ireland in the marathon.

Despite the effects of acculturation and assimilation in the several generations following the onset of the great Irish exodus, and notwithstanding the impact of intermarriage, suburbanization, upward social mobility, and the dwindling of immigration, Irish heritage and culture remain vibrant in Rhode Island.

Traditional Irish fraternal groups continue to be active. These organizations, though primarily for socializing, also engage in constructive social and cultural efforts. Meanwhile, the strong Newport Irish community and their Pawtuxet Valley counterparts faithfully continue their impressive St. Patrick’s Day parades in Newport and West Warwick each year, and Providence has revived its parade as well.

Although it is now more than three centuries since the first Irish pioneers settled in Rhode Island, the Irish community remains a distinct and vigorous presence in Rhode Island. Local Irish traditions are much in evidence, interest in the ancestral homeland continues strong, and the tendency of Irish Americans to identify themselves as such is pronounced and decisive.

The massive Irish Famine Memorial, occupying since 2007 a prominent location along the restored waterfront at Riverwalk in Providence on Point Street, gives permanent and prominent testimony to the historical fact that the Irish have exerted a significant impact on Rhode Island in every walk of life. In few other American states, if any, has the Irish community been so prominent in relative numbers and achievements.