Today, August 9, 2019, marks the second Black Ships event held in Bristol by the Japan-America Society and Black Ships Festival of Rhode Island, Inc. This event is a tribute to Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry.

Although, Matthew Perry, whom we honor, was born in Newport, this is an historical and cultural observance and Bristol is renowned for both. In addition, the Perry family’s connection to Bristol has been significant and enduring.

Oliver Hazard Perry by Edward L. Mooney, after John Wesley Jarvis, 1839 (Navy History and Heritage Command)

Quaker Benjamin Perry came from Massachusetts to the Narragansett Country (as Washington County was then called) in 1704 for greater religious freedom. His son Freeman Perry married Mercy Hazard and lived with her in the South Kingstown village of Matunuck.

Their son, Christopher Perry, who plays a prominent role in our narrative, fought in the American Revolutionary War at the Battle of Rhode Island and then in the Continental Navy as a privateersman. While on one privateer voyage, he was captured off the British Isles and imprisoned at Newry in Ireland’s County Down. There he met and was smitten by a young Irish lass named Sarah Wallace Alexander.

Christopher escaped from the very loosely-guarded detention facility, made his way south to the port of Cork, and returned home by a very circuitous route. After war’s end he sailed back to Ireland and brought sixteen-year-old Sarah to America. The couple were married in Philadelphia where they landed. Soon after, they moved to South Kingstown.

Their romantic story produced two major results—Oliver Hazard Perry and Matthew Calbraith Perry. The name Calbraith was in honor of the son of Sarah’s guardian.

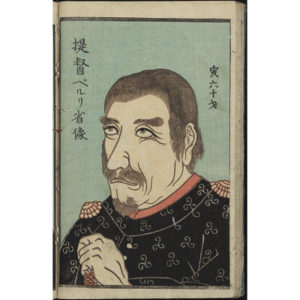

This portrait of Matthew Calbraith Perry, included in the Japanese book Ikobu Ochiba Kugo (“a basket for fallen leaves from abroad”), shows Perry with the prominent nose that the Japanese associated with Americans (Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait Gallery)

The audacious Christopher Perry, always the sailor, came to Warren, Rhode Island with his first son, Oliver, in 1798 to supervise construction of the 32-gun frigate General Greene, destined for service in the limited naval war with France, then being fought on the high seas.

Fifteen years later Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry won the pivotal Battle of Lake Erie, one of the three major American victories in The War of 1812 (Thomas MacDonough’s victory on Lake Champlain and Andrew Jackson’s overwhelming defeat of the British at New Orleans being the others). These three men of recent Irish ancestry took their revenge on England.

In 1814, Captain, and later U.S. Senator, James DeWolf, Bristol’s famous (or infamous) first citizen and, by far, the most successful privateersman of the War of 1812, held a victory party for Commodore Oliver that was attended by younger brothers Raymond (born in 1789) and Matthew (born in 1794). At that soirée, Raymond Perry, who had commanded a ship with MacDonough on Lake Champlain, met Marianne DeWolf, the daughter of Captain James.

Following the War of 1812, the three eldest Perry brothers came to Warren to supervise the building of a 16-gun brig-of-war designed by Oliver and named the Chippewa after a prize he took in the Battle of Lake Erie. He made Matthew the ship’s recruiting officer and Raymond served as his aide.

The wealthy James DeWolf not only financed the vessel for the U.S. Navy, he also provided living quarters in Bristol for the Perry brothers and their parents. That house was probably located on the east side of Hope Street about a quarter-mile north of Silver Creek. That stay began the long, continuous connection between the Perrys and Bristol.

After the Chippewa was completed, the familial union of the DeWolfs and the Perrys began. In 1815, the Chippewa’s officers formed an arch of swords as newly-weds Raymond and Marianne (DeWolf) Perry marched out of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church on Hope Street. Captain James furnished the couple with a home in one of his Bristol mansions.

However, Raymond, like his restless brothers, continued his naval activities. He cruised with Matthew in the early 1820s until illness ended his career in 1823. Raymond died in 1826 after fathering two sons. Marianne died in 1834. Their eldest child, James DeWolf Perry, firmly established the Perry family in Bristol in 1836 when he married Julia Jones, the granddaughter and heiress of Judge Benjamin Bourne, Rhode Island’s first U.S. Congressman.

Julia’s inheritance was a spacious home on the north side of Hope Street at Silver Creek. It dated from about 1680 and was built by Deacon Nathaniel Bosworth. Reputed to be the oldest existing house in Bristol, the structure and its surrounding thirty acres of land had been acquired by the famous Bourne family through the marriage of Ruth Bosworth to Shearjashub Bourne in 1747, the same process that gave the estate to the Perrys in 1836.

To further establish the Perry tradition in Bristol, Captain James DeWolf willed Hog Island off Bristol Point to his grandson and namesake, James DeWolf Perry in 1837. The will stated (in vain) that Hog Island was “hereafter to be called Perry’s Island.” By this will DeWolf gave his valuable Bristol waterfront property to the two children of Raymond and Marianne.

The descendants of Raymond and Marianne Perry owned the Silver Creek home until 1957. Some of those descendants still reside in Bristol. Their most notable progeny were grandson Rev. Calbraith Bourne Perry and Rev. James DeWolf Perry, a great-grandson, who became Bishop of Rhode Island and Presiding Bishop of the American Episcopal Church.

Since Raymond and Matthew Perry had served together on naval vessels for over a decade, we can assume that Matthew often visited Bristol to see his older brother and his nephews while on shore leaves and that he had frequent contact with this historic port town.

Having thus established the Perry presence in Bristol, we can examine the fate of the two most famous Perrys. On August 23, 1819, his thirty-fourth birthday, Oliver died of yellow fever while on a diplomatic mission to Venezuela to meet liberator Simon Bolivar, the George Washington of Latin America. A life-size bronze statue of this Perry stands at the front of our State House. The South Kingstown village near Wakefield where he was born is now known as Perryville.

Landing of Commodore Perry, Officers and Men of the Squadron, to Meet the Imperial Commissioners at Yoku-hama, Japan, March 8th 1854 (Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait Gallery)

Our honoree, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, the Newport-born younger brother of Oliver, was a career naval officer who served in the War of 1812, the Second Barbary War against Algiers in 1815, and the Mexican War. He gained the rank of commodore in 1840. By that time, he had also earned the title of “Father of the Steam Navy” for his efforts to introduce steam power into American naval vessels.

Matthew Perry’s great achievement, however, was diplomatic in nature. In 1853 and again in 1854, his squadron visited Japan and persuaded that insular nation to accept a treaty that “opened” Japan to Western influence and, ultimately, trade.

Perry’s first visit to Japan occurred from July 8 to 17, 1853 when he anchored in what is now known as Tokyo Bay off Japan’s east coast, just south of Kanagawa and Yokahama. He carried a letter of friendship from U.S. president Millard Fillmore, crafted in part by Secretary of State Daniel Webster. It contained a request for a formal relationship between the two nations.

Perry’s small flotilla of two steam frigates towing two sailing vessels reached Japan by way of Shanghai, China after stopping at then independent Okinowa Island. The initial landings were at the villages of Uraga and Kurihama in Yokosuka. Perry’s vessels were the first steamships ever seen in Japan. The isolated Japanese at that time referred to all foreign vessels as KUROFUNE, meaning “Black Ships,” because, unlike Japanese vessels, they used tar and pitch for caulking to prevent leaks. Perry’s steamships were not only foreign but also dark-hulled.

After giving the emperor time to respond to the U.S. overture, Perry returned to Japan on February 13, 1854 with a squadron of ten vessels to negotiate a maritime agreement. On March 31, 1854, after long and delicate discussions, Perry and four representatives of the Japanese emperor signed the Treaty of Kanagawa.

This agreement of peace and friendship allowed the United States to access two Japanese ports—tiny Shimoda and Hakodate. At these towns, U.S. ships could stop for coal, provisions, water, and wood, but could not trade. Shimoda and Hakodate were also designated as ports of refuge for shipwrecked American sailors.

After the signing, Perry cruised south to Shimoda arriving on April 18, 1854. Following 25 days of celebration, he left for the other treaty port, Hakodate, arriving on May 17th and departing on June 3rd after more festivities. Shimoda today conducts a large, annual Black Ships festival to commemorate the arrival of Perry’s fleet in April, 1854. Our festival is a small replication of these welcoming celebrations.

Upon his return to the United States, Perry was praised and rewarded by Congress for opening Japan to Western influence, although such progress at first was very slow. Before his death in 1858 at the age of 63, he prepared a valuable and beautifully-illustrated three-volume report on his Japan expedition.

In the 20th century Bristol developed two important connections with Japan. In 1924, Senator LeBaron Colt, a prominent resident of Bristol’s Linden Place, was chairman of the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Immigration during the struggle that led to the passage of the restrictive Immigration and Nationality Act of 1924. Although the measure lowered the annual quotas for Southern Europeans, such as the Portuguese and Italians, its most discriminatory feature was its Japanese exclusion section. Modeled on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, it declared the Japanese and other Asians as aliens ineligible for citizenship. They were forbidden to immigrate to America.

Senator Colt vigorously opposed this Asian exclusion, but the Senate and Congress overruled him. When Colt died unexpectedly later in that year, his family received numerous condolences from Japanese and Italian officials praising his fairness and humanity.

Three decades ago, my wife Gail and I purchased a large scrapbook containing these expressions of sympathy at a Boston auction and presented it to Linden Place. In July, 1990, a Japanese delegation came to Linden Place to view the letters and pay their respects to this Bristol humanitarian. (That event was covered by the always vigilant Bristol Phoenix.)

Nine years after Senator Colt’s death, a new Irish and American missionary order—the Columban Fathers—chose Bristol for their House of Studies. Their missionary apostolate included Japan. The Columban Fathers now maintain their former seminary on Bristol Point as a retirement home where several of the priests with Japanese connections now reside. I might add, given Bristol’s large Portuguese-American population, that Japan’s first Western missionary was St. Francis Xavier of Portugal who came to Japan in 1547.

In sum, the Japan-American Society and Black Ships Festival of Rhode Island, Inc. is a statewide organization in the same way that the Perrys are a statewide family and its support of Japanese culture and connections is a statewide concern. We are glad that Bristol has welcomed this festival with such cordiality and enthusiasm.

[Banner image: Landing of Commodore Perry, Officers and Men of the Squadron, to Meet the Imperial Commissioners at Yoku-hama, Japan, March 8th 1854 (Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait Gallery)]