Today, May 29, 2015, is the 225th anniversary of Rhode Island’s entry into the Union under the United States Constitution of 1787. For thirteen months prior to May 29, 1790 (i.e., since April 30, 1789 when George Washington was inaugurated as president), Rhode Island was an independent republic. It shared this distinction with North Carolina until November 21, 1789, when the “Old North State” ratified the Constitution. After that event, Rhode Island stood alone.

During the nineteenth century, Americans in their thirst for expansion created four other temporary independent republics. In 1810, while Spain was distracted by the Napoleonic Wars and revolt in her colonies, American settlers, encouraged by agents of President James Madison, seized Baton Rouge and declared the area eastward to the Perdido River—the present Gulf Coast of Mississippi and Alabama—“free and independent.” These aggressors adopted a blue flag with a lone star and asked the United States to annex them. Madison promptly complied, and during the War of 1812 the accession of the short lived Republic of West Florida was completed by General James Wilkinson.

A similar fate befell Mexico in 1835 when those Americans who had been invited to settle in the Mexican province of Coahuila, Texas (and given generous land grants to do so) staged a revolt against their adopted country on the stated ground that the new centralization of power in Mexico City denied them local autonomy. The fact that Mexico had abolished slavery in 1829 and was a Roman Catholic nation that required settlers to become Catholics in order to own land were not among the proclaimed abuses, but they were really the driving forces.

On March 2, 1836, the Americans adopted a declaration of independence and created the Republic of Texas under the leadership of Sam Houston. After reverses at the Alamo and Goliad, Sam Houston, aided by numerous American volunteers, defeated Mexican President and General Santa Anna on April 21, 1836 at the Battle of San Jacinto. The victorious Republic of Texas immediately sought annexation, but the issue of slavery delayed the admission of Texas to statehood until 1845 when this action precipitated the Mexican War.

At the outset of that conflict, aggressive American frontiersmen created a republic in northern California on Mexican soil. In June 1846, with the help of a U.S. Army “exploring expedition” headed by Captain Charles C. Fremont (“The Pathfinder”) and his famous scout Kit Carson, these Americans proclaimed the “California Republic” and adopted a flag depicting a bear as its emblem. By January 1847, all of California had been conquered, and in September 1850 the former “Bear Flag Republic” became America’s thirty first state. We were fulfilling our “manifest destiny” to overspread the continent from sea to shining sea.

Hawaii became the final U.S. republic. Its acquisition and annexation followed a familiar pattern. In January 1893 a bloodless coup led by American sugar planters and merchants, with the assistance of American Marines from the USS Boston, ousted Polynesian Queen Liliuokalani. The revolutionaries immediately sought annexation, but America’s highly principled President Grover Cleveland regarded the revolt as unjustified. He sent ex-congressman James H. Blount to investigate the role played by the United States in this overthrow. As a former Confederate cavalry colonel from Georgia, Blount may have been a little upset when Queen Lil’s Royal Hawaiian Band, desirous of making him feel at home, played the Union war song, “Marching through Georgia” to welcome him.

Despite this incredible diplomatic faux pas, Blount determined that the U.S. improperly aided the revolution, so Cleveland refused annexation. This rebuke notwithstanding, Sanford B. Dole, president of the provisional Republic of Hawaii, refused to restore the monarchy. Eventually in August 1898, after Commodore George Dewey seized the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, President William McKinley and the Congress granted the Hawaiian republic’s plea for annexation.

The Republic of Rhode Island—unlike those in West Florida, Texas, California, and Hawaii—did not clamor for union with the United States nor was it tarnished, like them, by ignoble origins. Rhode Island remained resistant because it could not eagerly embrace a constitution that countenanced slavery, lacked a Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties, and threatened state sovereignty. It also believed, consistent with its democratic tradition, that such a basic law should be ratified by the people directly, not by a convention. (Rhode Island had been the only state to permit a direct vote on adoption, and the proposal was soundly defeated in 1788.)

Alone among the other republics (including North Carolina), Rhode Island was pressured and coerced by the national government to join the Union. Congress threatened Rhode Island with tariffs, debt collection, and commercial isolation to compel its ratification of the Constitution. Massachusetts and Connecticut hungrily looked on, considering what parts of Rhode Island could be annexed to them. On May 29, 1790 Rhode Island finally yielded, but its convention ratified the Constitution by the narrowest margin of any state—34 delegates in favor and 32 opposed.

Considering the basis of Rhode Island’s opposition to the 1787 constitution—fear of an overweening and unrestrained central government, concern for the sovereignty and integrity of the states in the spirit of true federalism, solicitude for individual liberty, especially religious freedom, opposition to slavery and the incidents of servitude, and concern for democratic participation in the constitution-making process— we might ask not why it took the Republic of Rhode Island so long to join the Union, but why it took America so long, at least on these issues, to emulate Rhode Island!

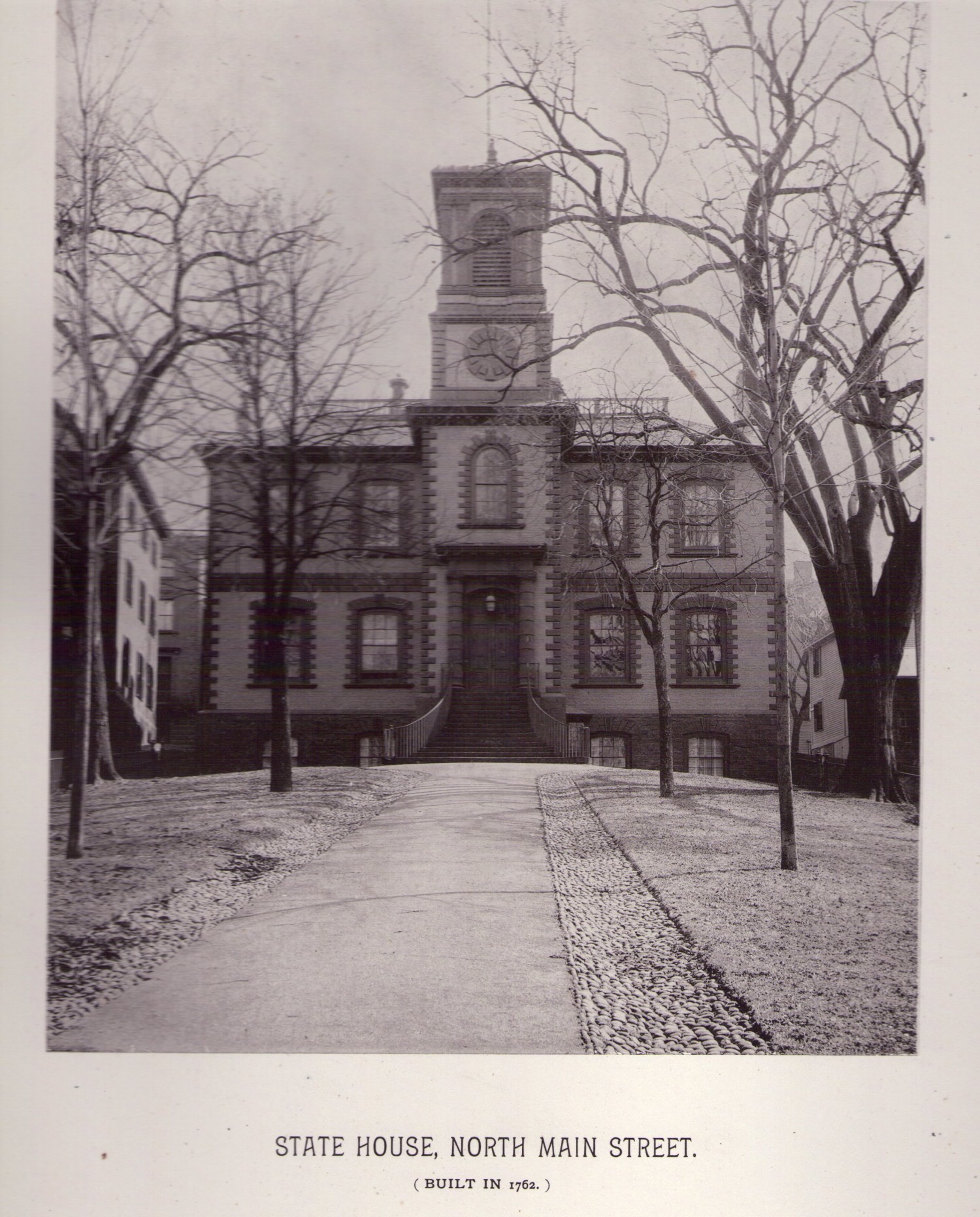

(Banner Image: Old Providence State House, built in 1782, image taken in 1886 (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)