The Idea for Rebuilding

In 1966, a young Harvard graduate in Rhode Island with a passion for naval history noted that the American Bicentennial was approaching. No one else seemed to be paying any attention to this milestone event just yet, but John Fitzhugh Millar thought that Newport, as the heart of a maritime state and the place which prompted the founding of the Continental Navy, ought to contribute to the expected national celebration by focusing on the maritime aspect of Revolutionary history. Eventually, Millar selected five ships he thought could tell the story of the birth of the navy and set about getting reproductions built. Surely, with this much lead time, money could be raised and ships could be launched. Surely, many people would be interested and financially supportive.

Or not. While plenty of people thought that a tall ship celebration was a fine idea, no one was willing to contribute funds. So Millar turned to a local bank in 1968, the manager of which initially gathered the staff together for the express purpose of laughing at the young man and his idea of building five full-size Revolutionary-era ships. When Millar persisted, the manager promised $250,000 to build one ship if a shipyard could be found that would do it for that little. The manager then sent Millar on his way, never expecting to see the young man again. But the bank manager underestimated him – a few months later, Millar found an experienced shipyard in Canada in need of additional work and returned to the bank to collect his loan. The manager had to give it to him.

This loan was not to build the replica of Providence, but one of her early enemies, HMS Rose.

Given his financial limitations, Millar chose to build Rose, the largest of his envisioned fleet because of all the stories it could tell. It took several years, but Rose was launched in 1970 and created a lot of interest. Rhode Island’s Lieutenant Governor made Millar a founding member of the Rhode Island Bicentennial Commission and Millar promptly suggested that the Rhode Island Commission invite the commissions of other states to band together into a larger organization to raise money. The resulting Bicentennial Council of the Thirteen Original States was able to raise millions for bicentennial projects over the next few years.

By 1973, they had enough money to move forward with the next part of Millar’s plan. He created a nonprofit organization dubbed the Seaport ’76 Foundation for the purpose of taking responsibility for Rose off Millar’s shoulders and to fund the construction of the additional ships, starting with Providence. These men, mostly former naval and marine officers, insisted that the replica of a ship as important to the American Revolution as Providence must be built in the United States. Millar argued that the cost differential was prohibitive – the Canadian shipyard he’d used for Rose could build Providence for $150,000, but building her in Rhode Island would cost $1.6M. The board was unmoved. Providence had to be built in the United States.

The Construction

And so it was. Providence was built in a disused section of the U.S. Navy Base at Newport over the course of two years. No plans for the original ship existed, but Rhode Island sloops of her type were common, so designing a reproduction was not particularly difficult. There were also several paintings depicting Providence, and a few models based on intelligent guesswork. The models were flawed and the artwork lacked detail, but based on the evidence at hand, the plans the naval architect drew for the reproductions were certainly very close to what the original Providence must have been like.

Only one significant change from the original was made — the new Providence would be built with a heavy-gauge fiberglass hull instead of wood, which has a lifespan of only 15 years. The board agreed that this was appropriate for the sake of longevity and maintenance. However, one member of the board had more ideas about her construction. This board member – without informing the rest of the board – called the naval architect, Charles Wittholz, with requests. The original Providence had a reputation as a fast ship. Could the architect make some modifications to make her sharper? Yes, that could be done. The board members also had plans to sail her in the Inland Waterway, so could her keel be made shallower with a draft of only eight feet? Yes, that could be done as well. And so it went. A few weeks before the ship was due to be completed, the architect called Millar. He had made the requested modifications, but now his calculations for stability showed that the modified ship would not meet Coast Guard standards. What would Millar have him do?

Stunned, Millar quickly came up with some fixes of his own. First, the amount of sail would have to be reduced. Second, an additional lead keel would have to be added along the length of the ship to increase stability. The increased draft meant that the ship would never sail the Inland Waterway, but that couldn’t be helped. Lastly, a “dolphin striker,” a vertical spar pointing downward from the bowsprit, was added despite the fact that Millar could not find any evidence of dolphin strikers being used prior to 1792. Even with the reduced sail area, the tension on the bowsprit would be too much without the striker. It had to be done.

It was enough. The ship was completed and Coast Guard-approved. It was not quite as historically accurate as planned, but still pretty close. The new Providence was completed in October 1976. While the highlight of the Bicentennial was the Fourth of July, celebrations took place over the entire year, so Providence was able to take part in a number of events.

The rebuilt sloop Providence on one of its first sails, in 1976 in Narragansett Bay (Heritage Harbor Foundation)

Christian McBurney in the foreground checking his musket, with his brother Shaun McBurney in the background sitting on the railing, on one of the first sails of the rebuilt sloop Providence, which occurred in Narragansett Bay in 1976 (Dr. Alexander McBurney)

The Board Has Other Ideas

Around 1980, they informed Millar that they actually did not intend to exhibit Providence with Rose as part of a Revolutionary-era fleet, in fact, they had no interest in Rose at all. Also, they did not want to build any more ships because they were just too expensive to maintain, insure, and repair. Instead, they wanted to have fun sailing Providence around. Millar was heading off to graduate school that fall and in no position to pay the costs by himself, so he made plans to sell Rose and then resigned from Seaport ’76.

The Senator John Warner Maritime Heritage Center, Home of the Tall Ship Providence, at the waterfront in Alexandria, Virginia, September 2023 (Christian McBurney)

The Interim

Providence was left in the hands of the board members, who did have fun sailing her around. They were not able, however, to raise enough money to support her, and Seaport ’76 was bankrupt by 1995. Providence was going to be sold to an organization on the West Coast when the mayor of Providence, Rhode Island, “Buddy” Cianci, stepped in and convinced the creditors to donate their interests to the city. For the next few years, the sloop served as a symbol of the city and was used to take high school students on short sailing ventures around Providence Harbor. When the next mayor was elected, however, he felt this was a luxury the city could ill afford. The city created the Providence Maritime Heritage Foundation to take over responsibility for the ship, which developed a number of programs and experienced some success. They conducted sail training and participated in tall ship events.

In 2004 the Foundation leased Providence to the Walt Disney Company to appear in the second and third movies of the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. But in 2005 the Foundation ran into financial difficulties that could not be overcome. The ship was put in dry dock, where it slowly fell into disrepair.

The Rescue

In 2011, the city sold the ship to a charter-boat captain, Thorpe Leeson. Captain Leeson used Providence for charter sails out of Newport and took good care of the ship for about four years. Then, in February 2015, a severe winter storm struck while Providence was in dry dock in Newport Shipyard. One of her jack stands collapsed, the ship fell, the mast and spars were shattered, and the jack stand punched a large hole in the hull. Leeson listed the sloop for sale to anyone interested in restoring it, and in 2017 Providence was purchased by the Tall Ship Providence Foundation for the express purpose of restoring the ship to its previous glory and using it as the centerpiece of the new maritime museum experience in Alexandria, Virginia, later named the Senator John Warner Maritime Heritage Center, Home Port of Tall Ship Providence.

It took nearly two years of work, but under the guidance of Master Shipwright Leon Poindexter, Providence was repaired and restored to its original appearance as a sloop of the Continental Navy. After arriving in Old Town Alexandria in 2019, additional electrical work was done and further restoration work completed so that the ship could meet the current standards for Coast Guard approval.

Reenactors, one reenacting Captain John Paul Jones and the other a crewmember, ready to give tours of the sloop Providence at Alexandria, Virginia (Christian McBurney)

About the Foundation

The Tall Ship Providence Foundation (TSPF) is a 501(c)(3) educational organization formed in August 2017 by business leaders based in Alexandria, Virginia. Its mission is to educate visitors on the role the Continental Navy played in the American Revolution using Tall Ship Providence as its anchor.

TSPF acquired Providence in 2017 and conducted a 30-month “keel to masthead” restoration, returning the ship to her authentic beginnings with a few modern conveniences. Serving as a floating classroom, guests will learn about Providence, see where sailors lived, meet Captain John Paul Jones, who will enthrall them with a sea story or two, and view a film, Providence: Dawn of the U.S. Navy, created especially for the Maritime Heritage Center. TSPF has an independent board representing a wide range of industries and an Advisory Committee of eight former Secretaries of the Navy.

Here is the link to the sloop’s website: https://tallshipprovidence.org/

The Original Providence—Its History

The Early Years

The sloop Providence was originally named Katy and was one of a fleet of ships owned by John Brown of Providence, Rhode Island. Records of the ship’s voyages start in 1769 and show that Katy was used as a merchant ship, privateer, and whaler in its early years. The sloop’s style was a common one in Rhode Island, featuring a fore-and-aft rigging style that allowed the ship to sail closer to the wind than square-rigged ships, which made her faster and more maneuverable. This appealed to both traders and pirates.

In June 1775, Katy became the flagship of the tiny Rhode Island Navy, created to protect the interests of Rhode Island merchants against British naval captains. These captains were aggressively enforcing British tax laws that fell heavily on the maritime trade that made up a large portion of the Rhode Island economy. Realizing that their two-ship navy could never truly protect their interests, in August the General Assembly requested that Rhode Island’s representatives in the Continental Congress initiate legislation calling for the formation of a Continental Navy.

After a great deal of debate, on October 13th, 1775, legislation was passed authorizing the purchase of Katy and another ship to serve as the first ships of a new Continental Navy. The passage of this legislation is why October 13th is still celebrated as the birthday of the U.S. Navy today.

As Katy was on another mission at the time, four other ships were commissioned before Katy arrived in Philadelphia to be refitted for service. When the ship was commissioned, it was renamed Providence in honor both of its city of origin and the fact that all the Rhode Island delegates to the Continental Congress were from Providence.

Painting depicting Continental Sailors and Marines landing on New Providence Island, Bahamas, on March 3, 1776. The sloop Providence is the most prominent vessel in the background. By V. Zveg, 1973 (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Continental Navy Accomplishments

In early January, the entire fleet sailed southward on its first mission. Encountering terrible weather and illness, Commodore Esek Hopkins (also of Providence, Rhode Island) decided to reroute the fleet to the Bahamas to search for gunpowder, a military necessity that was in extremely short supply in the colonies. When they reached the Bahamas, Providence was the ship used to land the Marines aboard the fleet in their first amphibious landing on foreign shores.

After returning to New England, command of Providence was transferred to a Scot named John Paul Jones, who had been serving as first lieutenant aboard another ship in the fleet. Captain Jones commanded Providence from May to November of 1776, an assignment he later described as his favorite command and with a crew he said was the finest he ever served with.

During those six months, captain and crew took 16 other ships as prizes for the Continental Navy, wiped out part of the Nova Scotia fishing industry (a significant food source for British troops), and became renowned for their narrow escapes and derring-do.

Shortly after Captain Jones left the ship in November, Providence — along with most of the other ships of the Continental Navy — was caught in the British blockade of Narragansett Bay and Newport during the winter of ’76 – ’77. It took about four months, but Providence was the first ship to break the blockade, escaping in early April.

Under the command of its former second lieutenant, John Peck Rathbun, Providence continued to take prizes and accomplish feats of seamanship that made the ship legendary. Among the most significant was the return to the Bahamas in early 1778, when Providence’s Marine captain John Trevett led an audacious raid on Fort Nassau, capturing the fort and leaving the Stars and Stripes flying above foreign territory for the first time when the crew departed a few days later.

During its four years of service, tiny Providence managed to take more than 40 prizes on behalf of the Continental Navy.

These ships and their cargoes were sold at auction in the nearest ports and the money divided between the Continental Congress and Providence’s crew. The most valuable capture of the ship’s career was HMS Mellish, carrying 10,000 British winter uniforms. Not only were these (crimson) uniforms diverted to Continental troops who desperately needed them, the British army was left without, creating great difficulties for British troops during the winter of 1776–77.

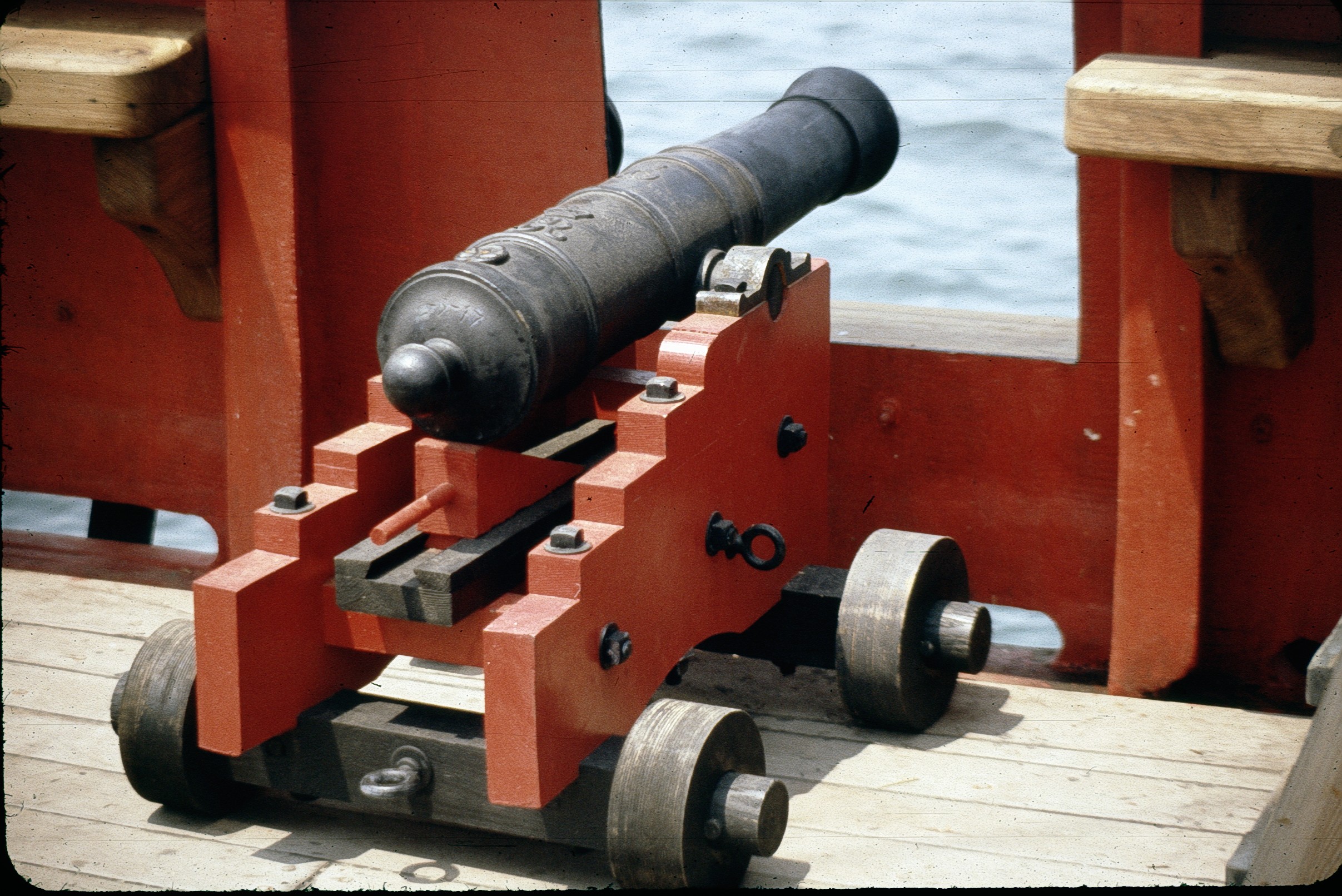

Cannon with naval gun carriage on the recreated sloop Providence, 1976. The scene is very similar to the one that can be seen today (Dr. Alexander McBurney)

The Burning

In late summer of 1779, Providence, along with most of the Continental Navy, was part of the Penobscot Expedition to eject British troops from a small peninsula in the part of Massachusetts that is now Maine. This should have been an easy victory for the Americans, who greatly outnumbered the British, but squabbling over tactics between the naval and land forces caused such significant delays that British reinforcements sailed up from Boston and the Americans were routed. A number of ships, including Providence, attempted to evade the British by sailing upriver, but were forced to concede defeat and burn their ships to avoid having them captured by the British. Providence was the last ship to go up in flames.

It was a sad ending for a ship which had served so well and accomplished so much. However, now that the reproduction is welcoming visitors, its stories will live on in a new generation.