In eighteenth-century southern Rhode Island a group of ambitious stock and dairy farmers attempted to create a landed, manorial gentry amid a rural New England dominated by villages, small farms, and few elites. Though their reign was short-lived, the Narragansett planters succeeded to a significant extent in developing a plantation-based economy. On a wider scale, they were New England counterparts to other colonials who intentionally created rural gentry communities. The most successful ones were located in the South where farmers grew tobacco, rice, and indigo for the market, but they were also to be found in New York’s Hudson River valley where vast grain plantations prospered. Wealth derived from commercial farming enabled the planters of the Narragansett country and elsewhere to attain their highest aspiration: to imitate the lifestyle of the English country gentry, who enjoyed social prominence, political influence, and a life of leisure and privilege.

South Kingstown, which then included the town of Narragansett, was the heart of the Narragansett country. Its planters were wealthier, more socially prominent, and more politically significant than their counterparts in the three other Narragansett country towns: North Kingstown, Charlestown, and Exeter. Examination of surviving written and artifactual evidence left by the planters in the town of South Kingstown provides an in-depth portrait of the conditions leading to the rise of their plantation economy, the community’s structure during its most successful era, and the factors that caused its decline on the eve of the American Revolution.

The Economic Activities of the Narragansett Planters, by Ernest Hamlin Baker. This mural showing the economic activities of the South Kingstown Planters, inclduing the production of cheese and the raising of Narragansett Pacers. It also shows the use of enslaved labor. The mural was in the Wakefield Post Office on Robinson Street for decades until it closed in 1999. Restored in 2000, it is now held by the South County History Center (South Kingstown History Center)

The Rise of the South Kingstown Planters, 1660-1730

Fortuitous circumstances in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries converged to permit the development of commercial farming and the formation of a planter class in South Kingstown by 1730. In short, rising demand from Newport merchants for livestock and produce to trade in foreign markets attracted ambitious stock and dairy farmers to the outlands of Rhode Island, including the Narragansett country. Some enterprising farmers took advantage of a long-running jurisdictional dispute between Rhode Island and Connecticut by purchasing large tracts of inexpensive Narragansett land and selling off parcels when land values began to climb once the disagreement was settled. This speculation gave these farmers the necessary capital to purchase more land, livestock, and enslaved workers.

Newport merchants in the seventeenth century discovered eager markets in the West Indies and southern colonies for livestock and provisions. The raising of staple crops in these areas became so profitable that planters chose to import foodstuffs and farm animals rather than set aside enough land to raise food for their own population. The merchants needed a hinterland to provide these goods. Between 1640 and 1690, lands around Newport and Portsmouth were quickly developed, and ambitious farmers on Aquidneck Island began to look west across Narragansett Bay in search of more land to raise cattle, sheep, and horses.

Land in southern Rhode Island, including Aquidneck Island and the Narragansett country, was well suited for developing a commercial farm economy based on grazing. The fertile soil, high-quality grass, and open pastures made the area ideal for raising livestock. Southern Rhode Island benefited from a mild climate and shorter winters, unlike the rocky and less fertile coastal lands of Massachusetts and Connecticut.

The lack of a Puritan hierarchy also contributed to the development of a commercial farming economy in South Kingstown. Puritan leaders in Massachusetts and Connecticut inhibited the development of their farm economies by tightly controlling settlement and land distribution. The legislatures ensured a gradual and orderly settlement of towns. Settlers were given permission to form a new town only when a sufficient number applied, usually at least forty families. Local leaders allocated the land. Taking after well-known customs in England, they decided how much land a villager received, determined who was qualified to enter the town, and apportioned undivided land as needed. Thus, a middling gentleman who had owned a farm in England received more land than a common laborer. Puritans adopted the village plan in settling their towns; houses and the church were clustered together while farms were located in the countryside. The purpose for this pattern of settlement went beyond the need for mutual protection against unfriendly Indians: Puritan clerics wanted to maintain an intimate connection with their congregants to ensure that they followed proper church teachings.

A cheese house and possible quarters for enslaved people on the Hazard Hoxie Farm, circa 1700 (Old Houses in the South County of Rhode Island, 57)

Initially, the four original towns of Rhode Island—Providence (1636), Portsmouth (1638), Newport (1639), and Warwick (1642)—followed the compact village plan. Portsmouth and Newport divided land among townsmen according to gradations of social status. A group of exiled Boston merchants received huge tracts, while most Aquidneck settlers were awarded relatively small land plots. But the attempt to impose a fixed social hierarchy and the compact village plan quickly broke down. Lacking a Puritan oligarchy and a strong legislature to control land distribution, Rhode Island developed a free market economy. Middling Aquidneck Island farmers, dissatisfied with their original allotments, sought to meet market demands for livestock and provisions. Land lust broke out in the colony.

In 1657-58, speculators from Portsmouth bought from the Narragansett Indians a twelve-square-mile tract in the heart of the Narragansett country. The land from the Pettaquamscutt Purchase, as the deal came to be called, eventually was named Kingstown and included parts of the present towns of South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Narragansett, and Exeter. The purchasers assigned thousands of acres to each member and offered the remainder for sale.

Widespread settlement of Kingstown, however, was inhibited by a serious competing land claim by the Atherton Syndicate, comprising influential Massachusetts speculators who used fraudulent means in 1659 and 1660 to obtain from the Narragansetts land that overlapped the Pettaquamscutt Purchase. A struggle over the competing claims immediately ensued. The Atherton Syndicate turned to Connecticut to validate its claim, and as a result that colony asserted jurisdiction over the Narragansett country. Throughout the remainder of the seventeenth century, both colonies sent envoys to London to argue their cases before royal councils and hassled settlers supporting the opposing side.

The presence of the powerful Narragansett Indians also discouraged settlement. That threat ended in 1676 when the Narragansetts were virtually wiped out in King Philip’s War. Before the climactic battle in Kingstown, the Narragansetts drove the settlers back to Aquidneck Island and destroyed their farms, rending the town “a desolate wildernesse againe . . . replenished with howling wolves and other wild, creatures” until settlers returned to rebuild their farms.

Although Connecticut officially did not concede jurisdiction over the Narragansett country until 1726, the matter really was settled by 1700. Since the lobbying in London ended in stalemate, the dispute was decided by which colony could attract the most sympathetic settlers. Connecticut settlers were constrained by the need to form entire villages and feared that their communities would become part of the heretic colony of Rhode Island. Although Rhode Island’s Baptists and Quakers feared a Connecticut victory, ambitious Aquidneck Island individuals took their chances and moved to Kingstown. Analysis of the previous residences of twenty-three of the forty-eight men recorded as living in Kingstown in 1671 reveals that ten moved from Newport, seven from Portsmouth, two from Providence, and one from Warwick. Only the remaining three came from Massachusetts or Connecticut. The free market economy in Rhode Island worked to the colony’s favor.

The few settlers who did venture into the anarchy of seventeenth-century Kingstown were able to acquire large tracts of cheap land. A Portsmouth farmer in the 1670s could sell his small farm worth about 150 shillings per acre and use the money to buy hundreds of acres in Kingstown for about 2 shillings each. Robert Hazard probably did exactly that when he bought 500 acres in Kingstown in 1671 for £28. Entrepreneurial men scrambled to earn money by any means so that they could raise cash to buy more land. Hazard worked as a surveyor for the Pettaquamscutt purchasers, and Nathaniel Niles served as a tenant farmer for a purchaser’s heir. Fortunate farmers also acquired land through family ties to the original settlers. The Gardiners and Watsons, for example, received land from purchaser John Porter, a relation by marriage, who willed 2,550 acres in 1678.

The early settlers sold parcels of their holdings to obtain desperately needed cash to develop their land into profitable farms. Land prices remained low, however, since the jurisdictional dispute discouraged widespread migration to Kingstown and left the town in disarray. By 1678 only 142 families had moved to Kingstown. A group of townsmen in 1679 sent a petition to the king urging that “he put an end to these differences about government thereof, which hath been so fatal to the prosperity of the place; animosities still arising in people’s minds, as they stand affected to this or that government.”

When it became apparent by 1700 that Rhode Island would win the dispute, an environment favorable for land speculation arose. By 1708 Kingstown’s population had increased dramatically to 1,200, making it the third most populous town in the colony, behind Newport and Providence. In 1723 Kingstown was divided into two towns, North Kingstown and South Kingstown. By 1730 South Kingstown had 1,523 inhabitants while 2,105 resided in North Kingstown. Population pressures increased the demand for more land and this meant rising land prices. Thomas Hazard, for example, purchased 900 acres for £700 in 1698 and in 1710 bought 300 acres for £500.

Enterprising landholders used the extra money from land sales to buy more livestock and enslaved blacks, an expanding source of labor for the planters. Rowland Robinson’s investments followed this pattern. In 1709, he bought 3,000 acres of the “vacant lands,” an area in Charlestown where Rhode Island wanted to promote the settlement of friendly families. Robinson made money from the tract by selling off parcels of 100 to 150 acres to settlers and invested the money from land speculation in his farming operations. By the time of his death in 1716 he had sold 2,700 acres of vacant lands. He was perhaps Kingstown’s greatest stockholder, owning at his death 666 sheep, 175 cattle, and 51 horses. Robinson willed to his only son, William, nine enslaved blacks and 680 acres of land.

The capital gained from land speculation and surplus stock and dairy farming enabled ambitious farmers to accumulate enough land to begin family dynasties and pass their new wealth and social position to their sons. Thomas Hazard, one of four sons sired by early settler Robert Hazard, used the base of his inheritance to acquire immense amounts of land. He made his first purchase in 1698 when he bought 900 acres on Point Judith, which he rented as tenant farms. Between 1703 and 1738, Hazard bought another 2,731 acres of prime land in South Kingstown and left his sons with ample estates. Commercial farming had enabled about a dozen families to establish a planter class whose position would remain firm up to the American Revolution.

Commercial Farming and Elitism, 1730-1774

By 1730 South Kingstown estates included unusually large stockholdings and landholdings. The wealthiest planters owned thousands of acres, exceptional by New England standards. Thomas Hazard by 1738 and William Robinson by 1751 each had purchased about 3,600 acres of land. William Gardiner willed 1,620 acres in 1732 and James Perry willed 1,440 acres in 1766. Planter landholdings usually consisted of several farms, each of which was large by Rhode Island standards. Consider the fifty-two farms ranging from 30 to 800 acres advertised for sale or lease from 1760 to 1766 in the Newport Mercury and Providence Gazette. Of the twelve of these farms that exceeded 250 acres, seven were located in South Kingstown, with acreages of 250, 265, 350, 400, 500, 550, and 800. The remaining five were dispersed in five different Rhode Island towns.

These farms were not only large, they were productive. Probate records indicate that the number of livestock owned by South Kingstown planters far exceeded those of Rhode Island farmers outside the Narragansett country. Eleven wealthy planters who had been among the highest tenth of South Kingstown taxpayers and died between 1730 and 1760 left estates averaging 391 sheep, 93 cattle, and 18 horses. Individual planters exceeded these averages. For example, Jonathan Hazard in 1746 owned 676 sheep, William Robinson in 1751 owned 162 cattle, and Jeffrey Hazard in 1759 held 44 horses. The wealthiest farmers in Portsmouth, Middletown, and Jamestown in this period had inventories averaging about 140 sheep, 20 cattle, and 5 horses.

South Kingstown was probably the premier cheese-producing town in New England. Its “Rhode Island cheese” and other stock and dairy products were traded to Newport merchants who then shipped the foodstuffs to the West Indies and the southern colonies. An English observer describing Rhode Island’s grazing economy in the 1750s wrote, “Their most considerable farms are in the Narragansett country. Their highest dairy of one farm ordinarily milks about one hundred and ten cows . . . makes about thirteen thousand pounds of cheese, besides butter, and sells off considerable in calves and fatted bullocks.” Another English traveler, Dr. Alexander Hamilton, met John Potter of South Kingstown, “a man of considerable fortune here,” while journeying down the post road in 1744. Hamilton spoke of Potter’s farm in impressive terms: “He has a large house close upon the road and is possessor of a very large farm where he milks daily 104 cows and had besides, a vast stock of other cattle.”

South Kingstown was also probably New England’s most important horse-raising town. Its settlers raised both carting and riding horses for planters in the West Indies and the South. The small, hardy Narragansett Pacers were a favorite breed, admired for their speed and comfort.

The former house and farm of Rowland Robinson, one of the wealthiest South Kingstown Planters of the colonial period. The farm, located near Saunderstown near the South Ferry Church, is beautifully preserved (Christian McBurney)

As most New England farmers maintained relatively small farms and livestock herds, slavery never flourished. The South Kingstown planters, however, needed a large, cheap labor force to tend to their great herds and to cultivate their vast farms. Not surprisingly then, South Kingstown also became the most important slaveholding town in rural New England. Enslaved black people were easily available for purchase from nearby Newport merchants involved in the African slave trade. Most were purchased prior to 1730. After that, the black population increased primarily by natural births. While blacks numbered no more than 3 percent of the total population in eighteenth-century New England, in South Kingstown between 1730 and 1774 they constituted 16 to 25 percent of the town’s population, as the enslaved population rose from only a few in the seventeenth century, to 85 in Kingstown in 1708, to 498 in South Kingstown alone by 1730.????

Though they probably underestimate the actual numbers, probate and census records indicate that the average slaveholding for South Kingstown planters ranged from 5 to 20. When he died in 1751, William Robinson, the third wealthiest South Kingstown resident in 1744, left 19 black slaves, the highest number among the town’s estate inventories. In 1840 Elisha R. Potter, Jr. of South Kingstown, a respected historian who undoubtedly conversed with relatives of planters, reported to the General Assembly that planters on the average held from 5 to 40 slaves each.

A South Kingstown planter often supplemented his enslaved labor force with one or two Indian servants. Taken mainly from the local Narragansett tribe, these Indians were probably hired to fill temporary work needs. An exception was the town’s wealthiest man in 1774, Silas Niles, who, according to that year’s census, hired 10 Indians in addition to owning 6 enslaved blacks.

Commercial stock and dairy farming was so profitable that some South Kingstown planters became involved in mercantile activities. For example, Robert Hazard in 1744 invested in two privateers. In 1753 Hazard bought shares in seven trading voyages from Newport merchant Jonathan Nichols. Additionally, Robert Hazard’s grandson stated that the planter often loaded two ships a year with horses and provisions from his farm for shipment directly to the West Indies. Hazard also probably acted as middleman, selling to Newport merchants farm products he had purchased from lesser farmers.

The elevated level of commercial activity enabled South Kingstown to support an unusually large planter class. Tax records indicate that the highest tenth of South Kingstown taxpayers between 1730 and 1760 owned from 45 to 50 percent of the town’s wealth, a concentration comparable only to New England’s port cities. The highest tenth of taxpayers in rural Massachusetts and Connecticut towns during this period consistently owned around 25 percent of the wealth. South Kingstown’s tax lists also demonstrate that wealth and family were important characteristics of the large planter class. The Hazard, Robinson, Gardiner, Potter, Niles, Watson, Brown, Perry, and Babcock families are found in the highest tenth of taxpayers from 1730 to 1774.

Wealth and family alone did not characterize the planter class. South Kingstown elites consciously imitated the English country gentry in their religious, political, and social lives. Rich planters sought to affiliate-themselves with churches of the elite class. Rural Rhode Island was dominated by Quakers and Baptists, but the austere and democratic nature of those churches did not appeal to every upwardly mobile planter. The Anglican and Congregational churches, previously confined to Newport’s merchant elite, made impressive gains in the Narragansett country. The Anglican meeting house built in 1707 in South Kingstown swelled with new members after 1721 when the Reverend James MacSparran assumed leadership of the parish. MacSparran was both orthodox and elitist, attitudes that endeared him to his new parishioners seeking to flaunt their recently acquired social status. Referring to the Quakers, MacSparran wrote, “wherever Distinction of Persons is Decried, as among that People, Confusions will follow: For Levelism is inconsistent with Order, and a certain Inlet to Anarchy.” Of course many of the town’s numerous birthright Quakers who could not accommodate their new wealth with the Society of Friends’ restrictions did not convert. They either attended weekly worship while forgoing monthly and quarterly disciplinary meetings or ceased to associate with any church.

Wealth also brought political influence. Other than Newport and Providence, South Kingstown was the most important town politically in the colony. Planters George Hazard, William Robinson, and Robert Hazard served as deputy-governor. Nathaniel Niles and James Helme served many terms as chief justices of the Supreme Court. Planter families also dominated leadership positions at the county and town levels.

As much as religious affiliation or role in public life, the physical environment created by the planters testifies to their wealth and aspirations. Unlike the archetypal rural New England community, villages were unimportant to the Narragansett planters. Only Little Rest (now Kingston) and Tower Hill came into existence, solely because they served at separate times as the seat for the county courthouse and jail. Churches and graveyards were spread throughout the countryside.

The houses of planters reveal a high level of cultural standards for rural Rhode Island. The interior of the large Rowland Robinson House, remodeled in 1755 and still standing today, includes a pleasant spiral staircase and several fine built-in cupboards. Pictures show that John Potter’s “Greate House,” built near Matunuck in 1742, was decorated with elegant wood paneling. Potter and other planters adopted the English custom of attaching high-sounding names to their commodious homes. Matthew Robinson called his house “Hopewell,” which was described as built in 1750 “after the style of the English Lodge.” Although South Kingstown society was somewhat refined, planters really looked to Newport’s cosmopolitan society for cultural leadership. The Newport merchants with whom planters traded were often richer and more sophisticated. For example, the interior architecture of the Rowland Robinson and John Potter houses reveal similarities to earlier Newport homes. Robinson and Potter apparently imitated patterns in Newport houses which had been constructed more than a decade earlier.

The decorative and fine arts left by the South Kingstown planters provide further evidence of the use and display of wealth. In the third quarter of the eighteenth century, South Kingstown remarkably supported four silversmiths, a number unmatched in rural New England, including Samuel Casey, among the finest at his trade in the colonies. Anglican planters also had their portraits painted by famous artists of the day. Sylvester Gardiner, son of William Gardiner, posed for John Singleton Copley. John Smibert painted Reverend MacSparran and his wife, the former Hannah Gardiner. Surviving murals from the John Potter and Rowland Robinson houses, though not painted by expert artists, are revealing. The Potter mural, now hanging in the Newport Historical Society, shows John Potter’s family enjoying tea on dishes of valuable porcelain and silver. Potter, a member of the Congregational church, wears a red coat with a ruffled shirt containing gold buttons. Three ladies are adorned in colorful dresses. The presence of an enslaved person adds to the atmosphere of wealth and status. The mural in the Robinson house shows the planter on horseback sacking a deer, a favorite sport of the English aristocracy at the time.

The image of South Kingstown planters as culturally refined, fun-loving socialites must be tempered somewhat. Some planters enjoyed their leisure time. Reverend MacSparran’s diary shows that dinner parties and corn-huskings were social highlights. Nicholas Gardiner’s wedding reception for his daughter was attended by a reported six hundred guests. Horse racing on Narragansett beach or on man-made circular tracks was a favorite pastime. But religious convictions restricted the behavior of many. The town’s Quaker planters especially avoided vanities, dancing, drinking, and other “frolicking.” Jeffry Watson’s diary, for example, reveals his preference for evangelical sermons over wedding receptions. A friend of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, the English traveler then residing in Newport, found trouble with South Kingstown innkeeper Immanuel Case one Sunday. Hamilton wrote:

Case was mightily offended att Mr. Laughton for singing and whistling, telling him that he ought not to profane the Sabboth. Laughton swore that he forgot what day it was, but Case was still more offended at his swearing and left us in bad humour.

Moreover, relations between planters were not always harmonious. Fierce competition over possession of land and political offices sometimes divided the planter community. Jeffry Watson in his diary mentions several disputes between local planters over land ownership, including one long and bitter struggle he had with his wealthy neighbor John Gardiner. Watson’s diary also includes references to the Ward-Hopkins controversy which rocked Rhode Island politics between 1757 and 1770. South Kingstown was primarily Ward country, as planters, led by Watson and James Helme, joined with Newport merchants. But Hopkins had solid support in the town, led by the Hazards. Watson, Helme, and their allies gained town and county offices when the Ward faction won the annual election for governor, while the Hazards replaced them when Hopkins was elected. In 1760 Watson described some typical electioneering for seats in the General Assembly. On 26 June he wrote, “I was at Little Rest where we met and set up William Potter and Hezekiah Babcock.” On 26 August Watson wrote, “I was at Town Meeting. Potter and Babcock was chose Deputies by 30 majority after a great deal of fending and probing. Hard words and a Great Strife but ended well.” Although political differences divided the planter community, South Kingstown’s elite social structure was never threatened.

The presence of enslaved blacks and Indian servants led to the creation of a very strict social order based on race, wealth, and family. Planters stood at the top of the social regime. For nonwhites, race determined the extent of their economic dependence on planters and of their legal rights. Enslaved blacks, depending almost totally on planters for subsistence and enjoying few legal rights, were at the bottom. South Kingstown supplemented Rhode Island’s slave code, described as the harshest in New England, with even harsher restrictions subjugating blacks.

As in other slave societies, terror was used to enforce the laws. Reverend MacSparran beat his enslaved male for breaking Rhode Island’s curfew law applied to people of color; he also beat his enslaved female for violating local law by receiving a gift from a male slave suitor without permission. An enslaved runaway who returned to his enslaver reportedly was stripped of his clothes, tied to a stake in a swamp, and left to the mercy of mosquitoes.

Indians and mulattoes occupied a slightly higher position. By law Narragansett Indians could not be held in slavery, and many lived in their own households. The 1774 census, for example, revealed that 99 of the town’s 220 Indians lived in their own households. But some were so destitute that they hired themselves out as field laborers or as indentured servants for a term of years. Social custom apparently demanded that mulattoes be used as servants. The low level of miscegenation in South Kingstown indicates that social pressures were aimed at upholding the regime based on race. A state census in 1782 reveals that one mulatto for every eleven blacks lived in South Kingstown; towns where slavery was less important maintained mulatto-to-black ratios of one to five, one to three, and even one to one.

Poor landless whites also enjoyed some freedom, though their opportunities were limited by the influx of cheap black and Indian labor. These whites depended on planters for employment but usually received only seasonal work. Only landholding whites had the right to vote. Small and middling white landholders in the voting class still often had to depend on planters to buy their surplus farm products and to supply them with goods.

A gorgeous silver teapot made by Samuel Casey, circa 1760. South Kingstown (then including Narragansett) supported five silversmiths in the colonial period. Casey was one of the most talented in all the colonies; his pieces can be found at the Boston Fine Arts Museum, Metropolitan Art Museum of New York City, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence, and many other museums (Silversmiths of Little Rest).

This social system made South Kingstown resemble the colonial South more than the English countryside. Planters in Rhode Island and the southern colonies were similar in kind: they both resided on isolated estates, engaged in commercial farming, depended heavily on an enslaved workforce, and dominated their communities socially and politically. Still, though South Kingstown’s gentry society was unique in colonial New England, southern planters enjoyed more land, social prominence, and cultural refinement.

Decline of the Gentry, 1770-1784

By 1774, South Kingstown planters confronted economic and demographic problems faced by towns throughout New England and some additional problems caused by the town’s economy. Increasing population, rising land prices, vulnerability of Newport merchants, over exportation of quality horses, movements to free the enslaved, and the American Revolutionary War speeded the planters’ downfall. At war’s end South Kingstown was not much different from other rural New England towns.

By 1770 a finite supply of land and growing population combined to make New England an increasingly overcrowded society. Family lands were divided repeatedly to accommodate the increasing number of young men in families. South Kingstown experienced these population pressures with other rural New England towns. Its white population had grown from 965 in 1730, to 1,405 in 1748, to 2,185 in 1774. As a preindustrial agricultural society, South Kingstown’s planters required at least 250 to 1,000 acres to maintain their level of commercial farming. South Kingstown, too, was becoming overcrowded.

It became increasingly difficult to inherit or purchase land. Planters faced the prospect of not being able to pass on as much land to their sons as they themselves had owned. William Robinson in 1751 left a will dividing 1,385 acres between nine sons and grandsons. The eldest son, Rowland, received the most land, the homestead farm, but that amounted only to 300 acres. This experience was repeated among the Hazard, Gardiner, and other planter families. At the same time, rising population forced land values higher throughout Rhode Island, making it difficult to purchase large estates to transfer the plantation system. Unlike Virginia planters along the James River, who purchased and developed huge tracts of land in the colony’s vast interior, South Kingstown’s farmers had no interior of which to take advantage.

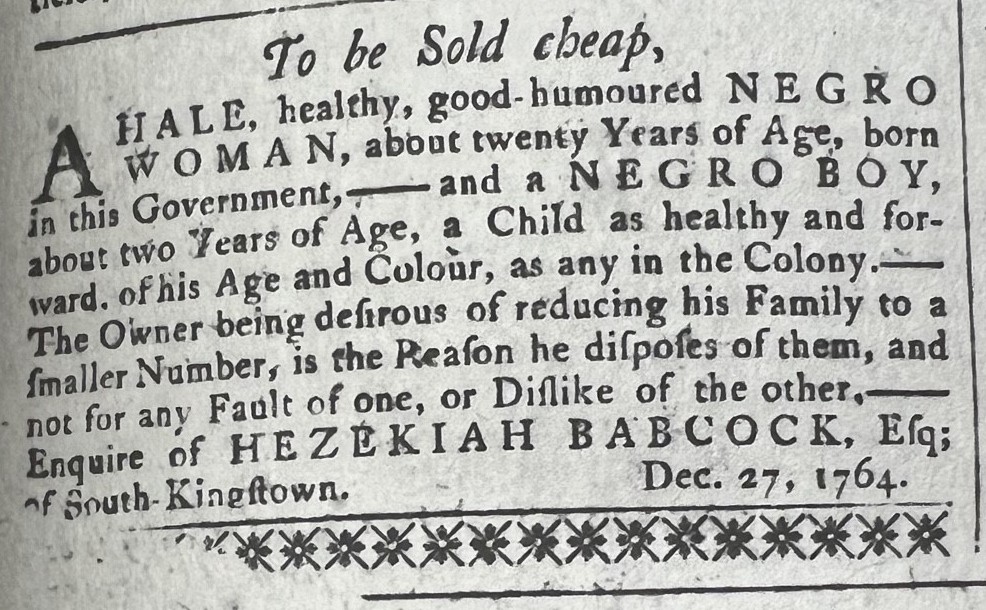

Hezekiah Babcock of South Kingstown, a planter, advertised the sale of an enslaved woman and her child in the February 4, 1765 edition of the Newport Mercury (Christian McBurney)

The division of family estates meant smaller stockholdings and a reduction in agricultural surplus. Inventories of planters who paid the highest tenth of taxes show a dramatic decrease in livestock holdings by 1774. As mentioned previously, eleven wealthy planters who died between 1730 and 1760 owned on the average 391 sheep, 93 cattle, and 18 horses. The average holdings of four planters who died between 1762 and 1774 fell to 166 sheep, 54 cattle, and 4 horses.

Slavery also became less important. Fewer laborers were needed to work the smaller farms and livestock herds. Four inventories from 1743 to 1752 listing the highest number of enslaved people averaged thirteen; from 1762 to 1771 that figure declined to six. In addition, South Kingstown Quakers, led by Thomas Hazard, increasingly opposed slavery. Following the example of Friends in Philadelphia, they threatened in 1771 to expel members who “kept slaves.” In June 1773, South Kingstown Quakers appointed to “Visit Slave Keepers” proudly reported that “they don’t find there is any held as Slaves by Friends,” and six Quakers who were among the highest tenth of taxpayers in 1774 did not have any enslaved blacks residing at their homes.

South Kingstown planters also were guilty of some poor farming practices, including over exporting their best breeding horses. Wealthy West Indian planters sent agents to Newport to buy all the best breeds in the Narragansett country. An advertisement appearing in the Newport Mercury on 28 March 1763 decried that “the best Horses of this Colony have been sent off . . . to the West Indies and elsewhere by which the Breed is much dwindled, to the great Detriment of both Merchant and Farmer.” Shortly after that advertisement appeared, Newport merchants sponsored a race open only to horses meeting quality standards. Though a purse of one hundred dollars was offered, only three horses entered the race, won by Samuel Gardiner of South Kingstown.

The planters also suffered because they depended on Newport merchants whose success was vulnerable to changing economic conditions. Surviving ledgers show South Kingstown planters sending great quantities of cheese, beef, hay, and livestock on the hoof to these merchants. In return the planters received imported luxuries from Europe such as linen, silks, chocolates, mirrors, and watches, in addition to necessities such as building materials and kitchen utensils. New England rum also was popular among the planters. Although Newport merchants prospered between 1763 and 1774, they lacked the larger hinterlands of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, and were susceptible to encroachment by the rising merchants in Providence and Bristol. Newport merchants were forced to rely on West Indian and other export trade at a time when production of food products by the Narragansett planters was on decline.

Disaster struck in 1775. A recession arrived in the foreign market trade, both in the West Indies and England. Business came to a stand-still. Aaron Lopez, the leading Newport merchant, admitted that he had to strain his resources just to pay four hundred dollars for ship repairs.

The Revolutionary War hastened the downfall of both Newport commerce and the South Kingstown planters. While the war’s effects on Newport are well known, its influence on the Narragansett economy are not. With the West Indies trade halted and Newport occupied by the British, South Kingstown planters lost their primary outlet for surplus farm goods. Furthermore, to replenish dwindling supplies, British troops invaded South Kingstown on several occasions in 1779, seizing sheep, cattle, cheese, and white and black laborers. Additionally, the town bore a heavy burden in paying Rhode Island’s war taxes. South Kingstown residents usually paid the third highest percentages of taxes in the colony, behind Newport and Providence. But the British and French occupations of Newport and the American army’s stay in Providence drained those ports’ resources. Thus in 1780 South Kingstown was assessed twice the tax paid by Newport residents and one-third more than Providence. Finally, the decline of slavery in the Narragansett country was hastened by legislative acts awarding freedom to any enslaved male capable of bearing arms who enlisted in Rhode Island’s First Regiment of Continentals and the manumission in 1784 of all children born to enslaved mothers.

The former Narragansett Church of the Anglicans. South Kingstown was unusual in having a rural Anglica Church, which was generally supported by wealthy colonists. In 1800, it was moved from rural South Kingstown to Wickford in North Kingstown, where it stands today (Christian McBurney)

By war’s end South Kingstown was no longer the gentry society of isolated estates and large farms. It was becoming more like other rural New England towns. Between 1774 and 1790 South Kingstown’s population increased from 2,835 to 4,131. Most farmers created only a small agricultural surplus; four men who were among the highest tenth of taxpayers in 1774 left inventories between 1788 and 1796 averaging only 50 sheep, 43 cattle, and 4 horses. Compact villages including Wakefield, Saunderstown, and Perryville were becoming important. Townspeople preferred to build their churches in villages rather than spread throughout the countryside. Significantly, in 1800 the Anglican meeting house located between Little Rest and Tower Hill fell into such disrepair that it was moved to Wickford. By the early nineteenth century the transformation of South Kingstown was so complete that the grandson of one prominent planter noted, “Few persons are now aware of the change that has taken place in the society here within the last fifty or sixty years.”