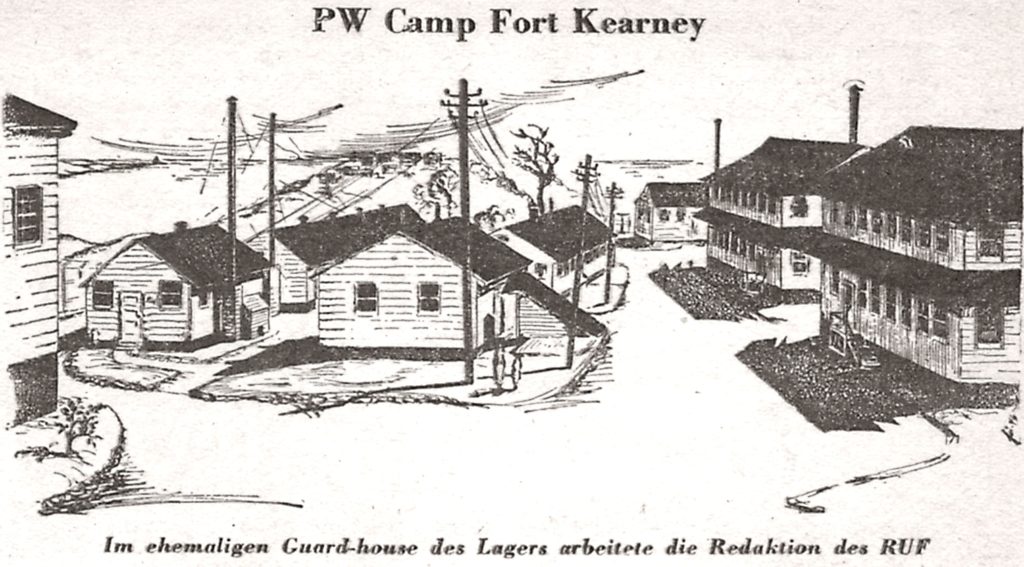

The site of the former Fort Kearney, at the end of South Ferry Road and about one mile south of the village of Saunderstown in Narragansett, is now occupied by the Narragansett Bay Campus of the University of Rhode Island. It may come as a surprise that in the waning months of World War II, the U.S. War Department chose this site as one of three small, unique prisoner-of-war camps for German captives in Rhode Island (the other two, Forts Getty and Wetherill, were located on nearby Conanicut Island, which encompasses the town of Jamestown). The camps were used in attempts to reeducate German prisoners away from their recent Nazi-dominated past and to prepare them for rebuilding a new and what was hoped for democratic society from the ashes of war-torn Germany.

This article is about the unique activities conducted at Fort Kearney. A companion piece, the following article, describes very different efforts made at Forts Getty and Wetherill.

Military policeman, with no gun, standing guard at the entrance of Fort Kearney (Edward Davison Papers, Yale University Library)

The story begins in early 1944, when prominent newspaper journalist Dorothy Thompson wrote an article about how cadres of hard-core Nazis dominated much of the life inside many German prisoner-of-war camps in the United States, beating up those who spoke out against Adolph Hitler and sometimes even murdering or forcing the suicides of anti-Nazi prisoners. Outraged at what was happening, Eleanor Roosevelt met with Thompson and U.S. Army officer Major Maxwell McKnight, and finally buttonholed her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, to see what could be done. This was the genesis of one of the most unusual Department of War units, the Prisoner of War Special Projects Division, established in the fall of 1944 by the Office of the Provost Marshal General.

The Special Projects Division faced the daunting task of trying to “denazify” and reeducate some 380,000 German POWs housed in several hundred camps across the country. As an initial step, fanatical adherents to Nazism were identified and moved to a special maximum-security camp at Alva, Oklahoma. The goal was to prepare the rest of the German POWs to return to postwar Germany and serve as a vanguard promoting democratic ideals and a respect for peace. This would not be an easy task, as Germans had spent more than a decade under Hitler’s rule, dominated by pro-Nazi propaganda and fearing jail or worse if they spoke out against the regime.

Lieutenant Colonel Edward Davison was appointed Chief of the Special Projects Division. Born in Scotland and moving to America as a child, he became one of the most gifted English-language poets of his day and a professor at the University of Colorado. An ideal selection, he had gained useful experience by serving as an officer with British Naval Intelligence during World War I.

Davison and his assistant, Major McKnight, were hesitant to push for reeducation, fearing retaliation against American POWs held in Germany. In addition, the Geneva Convention prohibited the indoctrination of prisoners. On the other hand, the convention’s Article 17 encouraged “intellectual diversions” at POW camps. The Special Projects Division, in a liberal interpretation of this last clause, chose a small number of well-vetted prisoners identified as having strong anti-Nazi views to work at creating “intellectual diversions” for their fellow POWs, in what became known as the “Idea Factory” or just the “Factory.”

On October 31, 1944, the Factory began operating at a former Civilian Conservation Camp in Van Etten, New York, which had been converted to a German POW camp replete with barbed wire, towers, armed guards, and strict rules. When the camp commander insisted on treating the Factory’s special prisoners like all the other prisoners—with daily roll calls, Saturday inspections, kitchen duty, and the making of beds—the Special Projects Division began to scout out a new location that would be larger and solely devoted to the Factor’s mission.

It found one at Fort Kearney, located on twenty acres in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, overlooking the West Passage of Narragansett Bay and Jamestown. Named in honor of Philip Kearny, a Union general killed in the Civil War, some time prior to World War II the U.S. Army added an extra “e” and began spelling the name of the fort as Kearney. (Some elderly Rhode Islanders who lived at the Narragansett Bay Campus in the late 1940s and 1950s still pronounce Kearney as “Cahnee” rather than the correct “Keernee.”)

Fort Kearney was constructed and garrisoned in 1908 as one of a number of coastal defense sites in the area. During World War I and the first part of World War II, these so-called Endicott forts were armed with heavy artillery designed to reach far out to sea. As the naval threat diminished by the start of 1945, most forts around the bay had their artillery removed and were deactivated. At Fort Kearney, a four-man guard belonging to the Harbor Defense Command maintained watch on the large, concrete gun emplacements left behind. With barracks for prisoners and their guards, as well as a kitchen and administrative buildings already in place, and with the grounds shielded from public view, Special Projects Division inspectors liked what they saw, and on February 27, 1945, Fort Kearney was reclassified. Almost immediately the special prisoners were transferred to the new location.

The first approximately eighty-five prisoners chosen for the special duty at Fort Kearney were a group of former German professors, writers, and artists who had successfully passed a number of evaluations confirming that they were ardent anti-Nazis. Most had served in the German army against their will, some had spent time in Nazi concentration camps, and all of them wanted to work to make Germany a different and better place after the war. Their story at Fort Kearney is not only how they helped to reeducate the German POWs at other U.S. camps, but also how they rose to become influential postwar writers and thinkers in their own right.

Kearney’s commander, U.S. Army Captain Robert L. Kunzig, was instructed to keep the camp’s role secret for several reasons. For one, many Americans had lost loved ones in the war in Europe and understandably hated Germans. Fueled by Allied war propaganda, the public often did not distinguish between Nazis and other Germans. Thus, there was concern the public would express outrage upon learning that some prisoners were being “coddled.” In early 1945, several newspaper columnists and radio announcers had already charged the War Department with “coddling” POWs. In actuality, many German POWs were not Nazi sympathizers and had fought for their country out of a sense of duty, pride, or fear. Kunzig became so concerned about the unauthorized disclosure of the camp’s activities that he decided to inform Rhode Island’s governor, J. Howard McGrath, of the camp’s purpose and to request that it be kept secret. McGrath agreed and gave an appreciative Kunzig help when requested.

Steps were also taken to protect the identities of the Kearney prisoners from Nazi prisoners. There was a fear that the names of anti-Nazi “rats” and “traitors” could be smuggled back to Germany where their family members would suffer the consequences. As one protection, the mailing address of the men who worked at the Factory was listed as Fort Niagara, New York, a regular German POW camp. Few photographs showed the faces of Kearney POWs.

While some prisoners volunteered to work at Fort Kearney, others took unusual paths. Raymond Hörhager was a prisoner at a POW camp in Arizona when he made the mistake of making a casual derogatory remark about Nazis. Put on a mock trial at the camp by an officer who had been a prosecutor in the Third Reich, Hörhager was sentenced to be tried as a traitor upon his return to Germany. The sentence for treason, of course, was death. Fortunately, the condemned man received help from a friendly camp guard who himself was a German Jewish refugee who had fled Germany in 1933. Two weeks later Hörhager was taken to another camp, where he was vetted about his anti-Nazi views. Along with a handful of others, he wound up at Fort Kearney.

Franz Wischnewski, a twenty-four-year-old artist who had been captured in July 1944 as a junior officer in the 114th Division, recalled being called out of his POW camp at Ruston, Louisiana, and told to bring his belongings. Accompanied by American guards who acted like they wanted to kill him, Wischnewski was taken on a three-day train trip, which likely ended at the Kingston, Rhode Island, train depot, and then was brought to Fort Kearney. A grateful Wischnewski suggested that the writer Alfred Andersch be brought to Fort Kearney and camp officials agreed.

Andersch had been a prisoner in the infamous concentration camp at Dachau. Forced to join the German army, in 1944 in Italy he deserted his unit on a bicycle and was captured by the Allies and brought to an anti-Nazi POW camp in Louisiana. Upset at being forced to leave this camp and go on a trip to an undisclosed location, upon being dropped off at Fort Kearney one night in about May 1945, Wischnewski later recalled, “tears welled in Andersch’s eyes” when he realized that Wischnewski and other prisoners he knew “were waiting for him.”

The Special Projects Division recognized that to gain the trust of these vetted prisoners and allow them to do their important work, it could not impose on them the same level of discipline as in other German POW camps. While Fort Kearney was surrounded by barbed wire, it had no armed guards or towers. Kunzig relaxed the discipline in his camp, explaining, “We had almost no problems at Kearney. Once in a while we’d have to sort of jack them up and make sure they kept their beds neat—try to keep it very military and correct. We had inspections, but at the same time there were no real pressures.” No prisoner ever escaped from Fort Kearney or tried to do so. Andersch recalled that a loudspeaker on the roof of the mess hall “woke us up every morning with a Duke Ellington version of ‘Lady be Good’ . . . .”

In order to remain at Fort Kearney, POWs were required to sign a remarkable declaration, given that Germany and the U.S. were still at war. It stated in part, “I declare that I owe no allegiance or loyalty to Adolph Hitler, the Hitler Regime, and the Nazi Party. . . . I further declare that I will strictly refrain from any activity which might be detrimental or appear hostile to the United States Government or the American people. I believe in a democratic way of way of life and am opposed to any form of dictatorship.” The declaration further provided, “I promise not to escape or to help others escape the control of the United States War Department . . . and to cooperate fully with the United States Army [personnel] appointed over me.”

Signing the declaration also meant the POWs had to renounce their German military ranks. This was intended to minimize potential friction and encourage an environment where all of the prisoners interacted as equals. POWs were also addressed as “Mr.” by the American guards and instructors. On the other hand, prisoners did have to wear clothes with “PW” imprinted on to them and to sleep in barracks as in other prison camps. However, the few images of the POWs at Fort Kearney indicate that sometimes they were allowed to wear khakis without the “PW” mark on them.

The November 15, 1945 edition of Der Ruf (Office of the Provost Marshal General, RG 389, National Archives)

The most important and time-consuming mission at Fort Kearney was the production of a German language POW newspaper intended for nationwide distribution to all German POW camps. Called Der Ruf, or in English, The Call, the newspaper was, as proclaimed on its masthead, “edited and prepared by and for German prisoners of war.” The primary goal of Der Ruf was to persuade German POWs to focus on the future rebuilding of their country and to abandon Nazi ideas. It was also intended to present the facts of the war honestly and to give an accurate picture of the American way of life. The paper was not intended to be a vehicle for voicing official American opinion or policy, although there were limits on what could be published.

The first editor-in-chief of the newspaper was Dr. Gustav R. Hocke, a prize-winning German novelist and newspaper correspondent who had been forced to serve as a civilian interpreter for the German Army in Sicily before being captured in September 1944. Hocke was supported by a remarkable staff of writers and other intellectuals who not only wrote the articles, but also, led by Curt Vinz, produced the layout of the newspapers at Fort Kearney. The newspapers were printed using offset printing presses on good quality newsprint at The Adjutant General’s Office’s Recruiting and Publicity Bureau on Governor’s Island in New York City. (For each German edition, about 500 copies of a mimeographed English version were sent to War Department and State Department officials who could not read German.)

The first issue of Der Ruf appeared in 134 POW camp canteens on March 6, 1945, and was priced at five cents. POWs were given small amounts of money for performing manual labor, and it was thought that if the newspaper was issued at no cost, it would be more likely seen as mere propaganda. The War Department’s role in promoting Der Ruf was not disclosed to POWs. The newspaper, with 11,000 copies distributed and supported by 500 advertising posters put up at the camps, created an immediate sensation. Nazis at a few camps bought the issues and burned them; at other camps they threatened fellow prisoners who intended to purchase the newspaper. At Camp Helen, Texas, for example, Nazi prisoners described the first edition as “Jewish propaganda . . . not fit for men.” Yet prisoners at many other locations received the publication with “overwhelming enthusiasm” and responded by purchasing all of the copies at their camp canteens.

Because some Nazi POWs tried to keep other POWs from purchasing Der Ruf, American prisoner commanders were able to identify them and remove them from positions of power in the camp or to send them to the Alva, Oklahoma, camp. For example, seven Nazi officers at Camp Trinidad in Colorado caught burning copies of the newspaper were immediately transferred to Camp Alva. Some Nazis also gave themselves away in letters they sent back to Germany, all of which were read and censored by U.S. military personnel. One prisoner wrote that Der Ruf was “supposed to be a political reeducation for us. But we are Nazis and we will remain Nazis and only laugh about it.”

One incident at Camp Fanning in Texas was typical. A POW managing the camp canteen, objecting to the newspaper’s contents, removed the issues from the store’s inventory. The American camp commander responded by temporarily placing the POW in solitary confinement, “on a diet of bread and water,” and returning the newspapers for sale. An American lieutenant then reported, “All issues of Der Ruf were sold in a few minutes after being placed on sale, and more copies have been ordered.”

By the time the fifteenth edition was issued on October 15, 1945, after issuing editions twice a month, 75,000 copies were printed, with sales totaling more than 73,000. One copy could be read by numerous POWs, consistent with one POW’s letter from Camp Concordia, Kansas, who wrote, “We circulate [the paper] by exchanging and handing it over to others.” The production, printing and distribution of Der Ruf did not end up costing American taxpayers—it actually earned a small profit.

POWs became bolder in reading Der Ruf. “When I read this newspaper,” one POW wrote in a letter-to-the-editor, a Nazi “came up to my bunk and yelled, ‘Traitors read such kind of newspapers,’ and that if I continued reading it, he would try to kill me. I didn’t pay much attention and continued to read the newspaper.”

The style of Der Ruf was intentionally “high-brow.” As many prewar German newspapers and magazines had adopted the same style, it was thought by some that if a more common approach was used, it would seem like propaganda. In addition, the intellectual elites at Fort Kearney wanted to reach their counterparts at the POW camps, in the hopes that they might instill democratic values in their less literate comrades. However, adopting this approach made the publication less influential with rank-and-file prisoners than it could have otherwise been.

One issue, intended to show that the Americans were not uncultured brutes as Germans had been taught, had a page of excerpts from Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Walt Whitman, Abraham Lincoln, Thornton Wilder, and Thomas Wolfe. Alfred Andersch wrote an article on his choices for the best American writers, including Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck. A third issue described the German tradition of free labor unions going back to the nineteenth century. Other issues focused on the strengths of the American political system and culture.

Captain Kunzig observed that the newspaper “was indoctrination by correct facts.” German soldiers, he noted, “weren’t used to correct facts and didn’t believe what they saw in Der Ruf until time proved how right the [newspapers] were and how wrong [Nazi] communiqués were.” Along that line, one issue described the horrors discovered by Allied armies at concentration camps and work camps. The Office of War Information provided the newspaper with the war reporting news the POWs craved.

POWs wrote hundreds of letters thanking Der Ruf’s staff. “Der Ruf is our favorite reading,” wrote Helmut Reiser of Camp Wheller, Georgia, “with impatience we are waiting for each issue in our camp.” Private Bruno Wittman from Camp Hood, Texas, complimented the newspaper profusely, adding, “What I like most in it is the truth, even if sometimes a bitter truth. But the eyes of many have now been opened.” Letters from POWs were overwhelmingly positive, but a few captives still had difficulty overcoming Nazi propaganda. Commenting on the statement in one edition that Hitler had declared war on the United States (which he had done a few days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor), one unbelieving POW wrote to the newspaper’s staff, “I wonder whether you can’t lie any better.”

American supervisors of the production of Der Ruf, led by Walter Schönstedt (sometimes spelled Schoenstedt), a German leftist émigré who had become a captain in the U.S. Army, encouraged free thought and gave the prisoners great leeway. Lieutenant Robert Pestalozzi, a Swiss-American, worked closely with the German editorial staffers, earning both their esteem and affection. War Department and State Department officials reviewed a draft English edition prior to publication, but it appears few revisions and omissions were required by them. The “Kearney Spirit,” mentioned by many of the Germans and Americans at Kearney, developed. The camp’s German spokesman, Gerhard Weiss, after the war defined it as “total cooperation between the Germans and Americans, without reservation.”

The German writers did not always agree with their American military supervisors, but the Americans were remarkably tolerant and did not insist that writers publish articles in which they did not believe. The most significant dispute surrounded American insistence on the policy of “collective guilt,” making all Germans responsible for starting the world war and for Nazi war crimes against Jews, Gypsies, Poles, Russians, and others. But, understandably, the Fort Kearney prisoners, some of whom had suffered in Hitler’s concentration camps, entirely rejected this notion and refused to reflect that view in the newspaper. One time an American officer travelled from Washington, D.C. to object to a proposed story of a German poet’s resistance to Hitler—the poet was ultimately shot dead by the Gestapo—on the ground that there had been no German resistance to the dictator. Imfried Wilimzig, a ballet dancer before the war, argued with the American officer, recalling later, “They obviously had no idea how many people in Germany weren’t Nazis.” Wilimzig won the argument and the piece was published unchanged.

On May 8, Germany surrendered to the allies. About a month later, the Office of the Provost Marshal, deciding that it was no longer necessary to keep its German reeducation program classified, issued a press release describing its work, including the production of Der Ruf (although the identity of Fort Kearney was still not disclosed). In the press release, Brigadier General B. M. Bryan, Assistant Provost Marshal, credited the newspaper, which had included accurate accounts of the progress of the war in Europe, with the lack of “serious demonstrations in camps” when the surrender of Germany was announced.

On June 28, the editorial staff presented a petition, signed by Hocke, Andersch, and others, complaining that “After these ten issues it becomes evident that . . . Der Ruf cannot maintain its old standard of quality and liveliness behind barbed wire.” The writers did not believe they could accurately describe American society without interacting with American civilians. Hocke, in particular, expressed frustration that he had “seen nothing of America except prisoner of war camps.”

The main reason for their discontent was that they yearned for what POWs wanted most of all: to return home as soon as possible to discover the fates of their loved ones. At a reeducation school run at Fort Kearney, the first graduates had been brought to the front of the line for repatriation back to Germany. In return for their loyal work, the petitioners also wanted to be among the first to return to their homeland as well and not be left behind to train more POWs who would be bound for Europe ahead of them.

In addition, in the next two editions of Der Ruf, the writers pressed hard against the doctrine of “collective guilt.” The August 15 issue blamed Hitler and Mussolini for being solely responsible for ruining peace efforts in 1939 and 1940 and for starting the war. In the next issue, the author of an article blamed the war on Hitler and the Nazi regime and for their using terror to eliminate the possibility of resistance. Neither piece even hinted at asking fellow Germans to accept some degree of responsibility for Nazism. There was room for compromise with both sides of this argument.

Major McKnight, who sympathized with the June 28 petition, recommended to his superiors that a new editorial staff be recruited as soon as possible and to permit the POWs on the current staff to be sent back to Germany. The recommendation was converted to an order and all of the POWs were also allowed to send letters to their family members. In August Hocke and ten other staffers were shipped to a POW camp near Cherbourg, France, to perform reeducation work there, before returning to Germany. Alfred Andersch was transferred to Fort Getty on August 25, and after passing the course there, embarked for Germany on October 28. Many of the original POWs departed Kearney in early December.

New editors, writers and production workers were transported to Fort Kearney and assumed their new positions in September 1945 and remained there until the paper was discontinued in late March 1946. One of the new writers was the intellectual Hans Werner Richter, captured with the 999th Division in November 1943. The change also presented an opportunity to resolve the main point of contention: it was agreed that Der Ruf would no longer contain articles rejecting the “collective guilt” doctrine, but that the Americans could not insist that staffers write articles blaming the German people either. One writer, Kurt Brockmeyer, served on the Der Ruf staff for its entire run, providing needed stability.

The prisoners at Fort Kearney had several important missions besides publishing Der Ruf. One was to monitor the newspapers published at other POW camps, which were typically printed on mimeograph paper, to detect Nazi influence. In March of 1945, it was found that out of forty-four camp newspapers examined, three were anti-Nazi; seven were nonpolitical; one was religious; twenty-five were Nazi; and eight were strongly Nazi. By the fall of 1945, through the replacement of Nazi editors at other camp newspapers, the influence of Der Ruf, other reeducation efforts, the gradual realization by POWs that the war was lost, and their interactions with Americans, a change of outlook had occurred: out of eighty camp newspapers studied, twenty-four had a democratic tendency; eighteen were strongly anti-Nazi; thirty-two were nonpolitical; three were religious; one was camouflaged Nazi; and two were militaristic.

The busy prisoners at the Factory also reviewed books proposed for use in POW classes, on library shelves and for sale in camp canteens, and translated American classics into German. The selections emphasized humanitarian values and individual liberties; some had been banned and burned by Hitler’s regime. “They sold like hotcakes” in the POW camps, recalled one Kearney writer. Prior to this effort, some schools in POW camps dominated by Nazis even required readings from Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf.

A rare image of the Der Ruf editorial staff at Fort Kearney, probably around August 1945. They are not wearing uniforms with PW on them. Alfred Andersch, wearing a sweater, smokes his pipe, and Hans Werner Richter stands behind the man sitting on the right. (Edward Davison Papers, Yale University Library)

Kearney prisoners also screened hundreds of radio programs and movies before they were shown at other POW camps, and recommended to drop those that showed the dark side of American life (such as gangster films) or were deemed to be overly propagandistic. It was even advised not to show films with bad acting and poor plots, as such films provided Nazi POWs with the opportunity of arguing that American culture was shallow. While watching most films was optional (they were very popular in the camps), POWs were required to view films of German atrocities discovered at concentration camps and the “Why We Fight” series sponsored by the War Department.

Professor Howard Mumford Jones, hired as an educational consultant, wrote pamphlets describing America’s institutions, history, and its people. Fort Kearney prisoners translated them into German—about 85 percent of POWs spoke only German. German and English versions of these and other pamphlets were distributed to POW camps. Jones also led Fort Kearney POWs in operating a pilot school to reeducate selected German POWs—the forerunner of the schools later established at Forts Getty and Wetherill.

A small staff of POWs, numbering about eight men and headed by Camp Spokesman Gerhard Weiss, supervised the administration of Fort Kearney from the POW perspective and helped to maintain its facilities. Jobs included a car driver for U.S. officers, two chefs, including a pastry chef, a manager of a commissary store, a manager of the canteen, a man who kept the barracks and other buildings supplied with coal, and a carpenter.

While the barbed wire at Camp Kearney protected POWs from the outside world, its American staff was not so protected. When the War Department was accused of harboring Communists, Professor Jones’s name cropped up and in August 1945 he resigned his post. At his August 6 farewell party, attended by Lieutenant Colonel Davison, Major McKnight, Captain Schönstedt, and other camp officers, Major G. B. Gemmill, sent from the Provost Marshal General’s Office, observed, “During the course of the evening, considerable ‘kidding’ was heard about them all being Communists, but at no time during the evening was there any serious discussion concerning either Communism or loyalty investigations.” Two days later, Gemmill noted in his memorandum that Professor Jones personally met with “all of the prisoners of war in the Factory and most of the American enlisted men” to say his good-byes. “All of the personnel at Kearney are very fond of Dr. Jones and are sorry to see him go.” Writing about the remaining officers and instructors at Camps Kearney, Getty and Wetherill, Gemmill concluded his memorandum with the following judgment: “my personal opinion is that there are no Communists among them. Everyone seems to be very earnest about his job and his responsibility.” Earlier in July, Lieutenant Frederic Handschy, an American officer who worked closely with the Der Ruf staff, was summarily transferred to another posting, presumably because of an accusation that he had Communist sympathies.

Still, on August 15, 1945, after hearing of the surrender of Japan, the American staff and the Fort Kearney prisoners celebrated the end of World War II. Following speeches from Captain Kunzig and Lieutenant Pestalozzi, and a prayer by Captain Richard Chase, a chaplain based in Fort Adams, a group of German representatives congratulated the American officers on the allied victory and solemnly promised “to cooperate, with all their strength, in the reconstruction of a new Germany in a peaceful Europe, based on the principles of democracy, humanity, and a sincere and enduring understanding of all mankind.”

Life was not all work at Fort Kearney. In addition to viewing movies, prisoners were allowed on the rocky Narragansett Bay beach next to the camp. The prisoners had time to read, write, draw, and paint, and once they created an art exhibition from paintings and drawings borrowed from the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence. They spent much time discussing politics and culture not only among themselves, but also with American officers at the camp.

German POW artist Franz Wischnewski, with Der Ruf production editor Curt Vinz sitting (Edward Davison Papers, Yale University Library)

Life at the POW camp was “really quite beautiful,” recalled Frank Wischnewski after the war. “Every day in Kearney was like Sunday.” However, Gerhard Weiss noted one drawback of Kearney, the “small space on which we had to live during the last year,” which meant that POWs could not play their favorite sport, soccer, or engage in other recreation “to the same degree as in a big camp.” POWs occasionally played fistball, a popular game in Germany similar to volleyball.

It appears there was almost no interaction between POWs and local residents before the war ended, but that there was some after that. Alfred Andersch recalled in a 1978 letter to Walter Schroder, with evident bitterness, “there was no contact” between the POWs from Fort Kearney and Fort Getty, and between the POWs “and the civilian population, as it was strictly forbidden. I do not know a single instance where a German prisoner was granted permission to socialize with the Americans, be it inside or outside the camp. Those were the regulations . . . .”

On occasion, prisoners (presumably working in camp administration) would jump into army trucks and be driven over the bridge to Jamestown and then travel by ferry to Newport to pick up supplies for their camp. On the ferries they would socialize with the other passengers. “I know this was true at Kearney,” explained Kunzig, “because I sent them.” Some stories go further and state that the other passengers did not know they were talking with German POWs, but that seems unlikely, given that the captives were always required to wear their prison clothes and typically had heavy German accents.

One Saunderstown resident, C. Michael Hazard, who was fourteen years-old when the POW camp at Kearney opened, informed one of the authors, “It was no secret to those of us who lived in its vicinity. I don’t remember seeing prisoners outside the camp, but I did get inside the facility on a regular basis and the prisoners appeared to be a happy, well-fed group. We used to go down to the camp, pay ten cents and watch current movies with the prisoners.”

Painting by POW Franz Wischnewski of fellow Fort Kearney POW Neumann. Signed and dated 1945 (Collection of the author)

Charles “Ted” Wright’s family used to live at the corner of Boston Neck Road and Saunderstown Road. He recalled that as a thirteen-year-old, he and his brother twice sneaked through the woods and walked up to the mesh fence surrounding Fort Kearney, where they engaged in pleasant banter with some POWs who were proficient in English. One POW even gave them a few cigarettes—apparently they were well provided for in that respect. Finally, an American officer, not wanting the POWs to mingle with locals, yelled at them in German and the POWs left the fence.

It appears that after Alfred Andersch left for Germany, perhaps beginning in November of 1945, a few POWs from Fort Kearney were allowed outside the barbed wire without escort. Ted Wright informed one of the authors that on a few occasions he saw POWs, in their prison clothes with “PW” stamped on them, walking north on Boston Neck Road—he suspects to the Twin Willows bar, which operated even back then. Neil Ross, who worked for eighteen years at the University of Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay Campus, over the years spoke with a few people familiar with the POW camp and heard that at days’ end and on weekends, the POWs were sometimes allowed to visit Wakefield, Narragansett, and Newport unescorted, even though they were required to wear their “PW” clothes. Ross heard stories of local residents being unconcerned as the German POWs strolled by or hitchhiked rides. If these incidents told to Ross did occur, presumably they occurred well after the end of World War II.

When sisters Elizabeth (Betty) and Louise (Lulu) Sheldon were college-age women, their family used to summer at their large shingled house fronting Narragansett Bay at Saunderstown, called Spindrift. Captain Kunzig, Lieutenant Pestalozzi, and a few of the other officers would sometimes visit their family and stay for dinner. Afterwards Kunzig would play the piano, Pestalozzi the accordion, and they would all sing along. The two sisters were skilled and avid sailors and would sometimes take the Kearney officers out on Narragansett Bay for a sail. They recently recalled that all of the officers spoke fluent German. Lulu said that once she was sailing a fifteen-foot boat alone “when I came upon a man swimming in the bay far out from Fort Kearney. He said, ‘Guten Tag!’ jovially and I waved. Might he have used my sailboat to escape? (Probably not, but it’s an amusing thought!).” Lulu recalled that she and Betty, still in the dark about the purpose of the POW camp, once were invited by Captain Kunzig to a candle-lit dinner at Fort Kearney, cooked by a POW German chef and served by a POW German former butler of a baron.

While the German POWs thrived in the relaxed atmosphere at Fort Kearney, the same cannot be said of the American guards whose duty was to watch over them. When a stickler for discipline, Major Frank Brown, visited the camp he found that when he entered the guard compound accompanied by another officer from Fort Kearney, only one of the twelve guards stood at attention, with the remainder sitting or lying on their beds. When Brown passed some of the POWs, he was irked that they did not stand at attention or salute, as was required at other camps. After he travelled back to his office, Brown personally began the paperwork to transfer some of the guards out of the post. New guards were brought in and trained to understand the rules they were expected to follow. Unlike the supercilious Major Brown, Lieutenant Colonels William Bingham and A. J. Lamoureaux of the First Service Command (covering New England), based in Massachusetts, were “proud” of Kearney, with the former calling it “the show place of the First Service Command.”

By the time of the November 1, 1945 issue of Der Ruf, the attempts at German reeducation were publicized to fellow POWs. In an account of the reeducation program, a POW author wrote that the efforts at Forts Kearney, Getty, and Wetherill were “probably unique in human history.” The author explained, “Voluntarily, German prisoners of war have undertaken to start a work of positive aid to their own fellows here in captivity . . . . They did it as men who believe in the future of their home country, a country that must become a part of a peaceful world.”

On November 30, at a farewell ceremony for many of the German POWs who had worked at the Factory for more than a year, held at the Post Theater at Fort Kearney, German speakers praised Davison, Schönstedt, Pestalozzi, and their professors. POW Karl Kuntze wondered that “Never before has a combatant nation, while the battle was still raging, undertaken to aid the enemy for the purpose of building up the possibilities for post-war peace.” Gerhard Weiss began his address, “For days our thoughts have been with our loved ones at home. We try to imagine the reunion with our families and contemplate what our personal future may be. Some are still without news from home. The uncertainty about the fate of their loved ones and the anxiety about their own uncertain futures constantly occupy their minds.”

The twenty-sixth, and final, issue of Der Ruf was distributed to camps on April 1, 1946. The newspaper staff also produced a magazine distributed to POWs as they boarded ships taking them back to Europe.

The German POWs and their American supervisors at Fort Kearney performed important work all out of proportion to their small numbers. They helped to reduce Nazi violence and influence in POW camps nationwide. They also helped to reduce tensions at the camps by accurately reporting war news. Most importantly, they helped to persuade many repatriated German soldiers returning to Europe to leave with a favorable impression of the United States and democracy. One survey of some 22,000 prisoners concluded that 74 percent of German prisoners left with “an appreciation of the value of democracy and a friendly attitude toward their captors,” while only 10 percent remained “militantly Nazi.” These “reeducated” returning POWs would play a role in the remarkable post-war transformation of Germany. Even though Fort Kearney cannot claim all of the credit for this change in outlook, it deserves a healthy share.

One returning POW, Paul Metzner, recognized the importance of what had transpired at Fort Kearney. He brought back with him a full collection of Der Ruf (probably the only other full collections are at the National Archives in Silver Spring, Maryland, and U.S. Army Museum at Carlisle, Pennsylvania). Metzner also brought back copies of art work drawn by Walter Junge, Walter Pöhls, and Huebscher, and poetry done by Richter and K.E. Meese. Paul’s son, Joachim Metzner, has retained these relics with pride and even visited the former location of Fort Kearney in 2015.

From “The Final Forty,” a poem/song written by, and with drawings by, POW Paul Metzner. Metzner has a squib on each of the last forty POWs at Fort Kearney. Showing on this page in the lower left is Hans Richter smoking a pipe, and a German POW about to swim in the icy bay (Collection of Joachim Metzner)

Fort Kearney closed down in April 1946 and its POWs were eventually repatriated to Germany. By October 1946, several of its buildings had been offered to Rhode Island State College (now the University of Rhode Island). Today, now expanded to more than 100 acres, the site is the location of the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

In 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Davison received the Legion of Merit for his work heading the Prisoner of War Special Projects Division. His files at Yale University indicate that he valued most his work with the Factory at Fort Kearney.

Professor Howard Mumford Jones, probably drawn by a Fort Kearney POW, showing Dr. Jones on graduation day, November 30, 1945. (Edward Davison Papers, Yale University Library)

Back in rubble-strewn Germany, the American soldiers, hardened by combat, when encountering the freed POWs cared little about their reeducation project. The American soldiers in occupied Germany “showed us their fists,” recalled one former Kearney prisoner. “It was quite a disappointment.” But they had been previously warned of the reception they would receive in the outside world by Professor Jones, whose speech to the first graduates of the Kearney school contained the following: “Outside the barbed wire, which, if it keeps you in, also keeps out the world, you are not loved. . . . the name of Germany is not a pleasant word. . . . You must therefore prepare yourself to face contempt and misunderstanding and hatred.”

Alfred Andersch, Hans Werner Richter and Curt Vinz began to publish their own version of the Der Ruf newspaper in occupied Germany, with the assistance of several others from their POW days in Rhode Island. Growing to a circulation of 100,000, it had a strong socialistic and democratic bent, and it also criticized American military occupation policy, sometimes harshly. Andersch and Richter promoted unity with the rest of Europe, but also wanted Germany to follow its own path and not be dominated by either the United States or the Soviet Union. Some articles were viewed as overly nationalistic, a taboo in occupied Germany. With the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union heating up in 1947, American military authorities cracked down and eventually shut down the newspaper.

In response, Andersch, Richter, other POWs from Kearney, and some of their friends held a meeting in a Bavaria village and formed what they called the Group of 47. According to Richter, “Its members were determined to prevent for all time a repetition of what had happened, and they wanted to lay the foundation of a new democratic Germany, a better future and a new literature, conscious of the responsibility in regard to politics and the development of society as a whole.” German-speaking Dan Stets, when he was a Providence Journal reporter, interviewed several of the surviving POWs in Germany and Austria in 1982. Stets wrote:

The Kearney experience . . . led these same POWs to establish a world-famous literary clique, Die Gruppe 47, the Group of 47, named for the year it was formed. They initiated a literary movement which helped rebuild German culture from the rubble of war and spawn and nourish younger, and, ultimately, even more important writers like Guenter Grass and Nobel laureate Heinrich Böll. The clique dominated German literature for two decades after the war—and it got its start here, in Rhode Island.

Alfred Andersch and Hans Werner Richter became well-known authors in postwar Germany and the most famous of the POWs at Fort Kearney. Each had a different take on this time spent there. Richter after the war claimed that he was forced to serve at Fort Kearney. It is improbable that he was involuntarily brought to Rhode Island. More likely, he made the claim after returning to Germany from pressure he felt to distance himself from charges that he collaborated with the Americans as a POW.

In one of his novels that was translated into English, Beyond Defeat, the main character likely represents Richter himself. While he hates the war and Nazis, he runs the tightrope of never betraying himself, his comrades in arms or his country. Interestingly, in the book, he never fires a shot at the enemy. When he is finally captured by the Americans in combat in hills near Cassino in Italy, he refuses to provide an American intelligence officer with information about his unit. At a POW camp in California, his friend is beaten almost to death by hardcore Nazis who control the camp under the noses of unknowing American guards. After the war, while still a POW, the main character criticizes the American reeducation effort, especially the collective guilt doctrine, asserts Nazi POWs were signing up for reeducation classes in order to speed their return home, and scoffs at attempts to democratize POWs. Despite that fact that Richter’s career as a writer and journalist began at POW camps, he puts a negative spin on them.

By contrast, in his autobiographical short-work, “The Cherries of Freedom,” Andersch celebrates his desertion from his army unit in Italy and turning himself over to the American army. His is a different kind of patriotism. He returned to Rhode Island in 1970 to deliver a lecture at Brown University at the invitation of one of his Fort Kearney instructors, Brown professor and poet James Schevill. As a result of that experience, Andersch wrote an autobiographical story of his visit, titled “My Disappearance from Providence.” While back on his brief visit to Rhode Island, Andersch drove to Saunderstown where he toured the countryside surrounding the old Fort Kearney site for the first time. He found there “old farms, weather-beaten frame houses surrounded by scrub oak and negligently harvested fields. They must have been there in 1945, when we were taken to the camp in tarp-covered trucks. As a prisoner, I had lived at the foot of the shore dunes, which hid the countryside, yet strange to say I had always imagined the countryside around Fort Kearney exactly as I finally saw it on that day in October 1970.”

After arriving at South Ferry, he parked his rental car and walked down to the shore. He wrote, “After an absence of twenty-five years I looked out at the white lighthouse in mid-channel, at the low hills of Conanicut Island, and at the mouth of the bay. . . . At the time my old camp meant a great deal to me, everything in fact. . . After all, it was in the seclusion of Fort Kearney, after years of fear and trembling, that I decided to become a writer.” The German author further recalled, “In Fort Kearney, in the germ-free environment of that luxurious prison camp, I also learned democracy. ‘Democracy,’ said Professor [T.V.] Smith, ‘is a technique of creative compromise.’ The idea appealed to me.” In a 1978 letter to Rhode Island author and historian Walter Schroder, Andersch said “the treatment we received in the American POW camps was excellent and a truly humane experience.”

[Banner Image: Wonderful drawing of Fort Kearney on the left (note two story barracks), Fort Getty on the right, the lighthouse on Dutch Island in the upper right, and the old Jamestown Bridge in the upper center. By POW Walter Junge (Der Ruf, Nov. 1, 1945) (Collection of the author)]For Further Reading:

The attempts to reeducate German POWs, including the efforts at Fort Kearney, have spawned a surprising number of books, dissertations and articles. The best of the early books are Judith M Gansberg, Stalag, U.S.A.: The Remarkable Story of German POWs in America (New York, NY: Crowell, 1977), which takes a positive view of U.S. efforts at reeducation; Rob Robin’s The Barbed Wire College, Reeducating German POWs in the United States During World War II (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), takes a more negative view (overly so, in the authors’ opinions). For the most balanced view and insightful analysis of the publishing of Der Ruf, see Aaron D. Horton, German POWs, Der Ruf, and the Genesis of Group 47: The Political Journey of Alfred Andersch and Hans Werner Richter (Lanham, MD: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014). See also Arthur L. Smith, Jr., The War for the German Mind: Re-educating Hitler’s Soldiers (Providence, RI: Berghahn Books, 1996) and Barbara Schmitter Heisler, From German Prisoner of War to American Citizen (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013).

Some helpful dissertations are: Pam Croley, American Reeducation of German POWs, 1943-1946, master’s thesis, East Tennessee State University, 2006; Charles Michael Muskiet, II, Educating the Afrika Korps: The Political Reeducation of German POWs in America During the Second World War, master’s thesis, Baylor University, 1995; and Anna Hermann, German Prisoner of War Programs in the United States including Fort Getty German Prisoner of War Camp, undergraduate thesis, Brown University, April 14, 2008 (includes interviews with ten former prisoners of war; copy also at Jamestown Historical Society).

An excellent article was written by Providence Journal reporter Dan Stets in 1982. Stets, who speaks German, travelled to Germany and Austria to interview several of the Fort Kearney POWs. Dan Stets, “’The Spirit of Kearney’” Late in World War II…,” Providence Sunday Journal (Magazine), July 18, 1982. Stets’s article can be purchased and downloaded for a reasonable fee at the online archives of the Providence Journal. Another excellent article, which can be found on a web search, is Ronald H. Bailey, “Lessons in Democracy: The secret and controversial attempt to teach German POWs about freedom while they were still in captivity,” World War II Magazine (August/September 2008), pp. 52-59. See also Genevieve Forbes Herrick, “Behind Barbed Wire,” The Rotarian, vol. 68, no. 3 (March 1946), pp. 22-24, which can also be found on the web.

For original records we reviewed, see Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, 1920-1975, RG 389, National Archives, Building 2, College Park, MD, and the Edward Davison Papers, YCAL MSS 787, Series I: Military Files, Yale University Library, New Haven, CT.

For Rhode Island’s coastal forts, see Walter K. Schroder, Defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II (Chapel Hill, NC: Professional Press, 1980). Schroder had also donated his helpful research files to the Rhode Island Historical Society, which include copies of contemporary Providence Journal and other newspaper articles, and provided additional information and comments for this article.

For works cited in this article by Richter and Andersch, see Alfred Andersch, My Disappearance in Providence and Other Stories (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977) and Hans Werner Richter, Beyond Defeat (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1950).

The authors received emails and spoke with Michael Hazard, Charles “Ted” Wright, Neil Ross, Louise (Sheldon) MacDonald and Elisabeth Kellog (Sheldon) Ascham.

The authors thank Joachim Metzner of Wolfsburg, Germany, for sharing with them his treasure trove of materials relating to the time spent by his father, Paul Metzner, as a POW at Fort Kearney. One unique document was a song/poem written by Paul Metzner, called The Final Forty, which provided a blurb on each of the last POWs at Fort Kearney.