On May 3, 1768, a man was killed in Newport, Rhode Island, in a fight on Thames Street near Green Dragon Lane.[1] Four days later, Sarah Goddard and John Carter published the first report of that “very unfortunate Affair” in their Providence Gazette newspaper:

a Quarrel arising between two young Gentlemen, Midshipmen, belonging to the Senegal Man of War, lying in that Harbour, and some People on Shore, one of the latter was killed, and another so dangerously wounded, that ’tis thought he cannot recover. The Coroner’s Inquest having sat on the dead Body, we are told, brought in their Verdict, wilful Murder.

On May 9, Solomon Southwick of the Newport Mercury reported more details about the violent confrontation:

…between 11 and 12 o’Clock, as Mr. Henry Sparker, Shoe-Maker, of this Town, and Mr. Philip Dexter of Providence, being in Company with some of the People belonging to his Majesty’s Sloop Senegal, now in this Harbour, commanded by Capt. [Thomas] Cookson, a Difference happened between them, which ended in a very tragical Manner; Sparker being run almost thro’ the Body, with a Sword, as ’tis supposed; by which he died in about an Hour after; and Dexter received a Stab in his right Side, and had his head very much cut and mangled, by which his Life is still in Danger.

The Senegal’s Men concerned in this unhappy Affair are Mr. Robert Young, Mate, Mr. Thomas Careless, and Mr. Charles John Marshall, Midshipmen; who are now confined in his Majesty’s Jail in this Town, and are to have their Trial on the first Monday in June next. As yet it seems to be a little uncertain who were the first Aggressors in this melancholy Event, the Particulars must therefore be deferred till after the Trial.

The legal filings make clear that the officer who actually stabbed Sparker was Midshipman Thomas Careless (or Carless). Suffering a wound four inches deep, the shoemaker was taken into the nearby house of Elijah Knap and died.[2]

Southwick told his readers that he had omitted some details from his newspaper so as not to prejudice a jury. But his omissions also served to make Newport look more respectable. Up in Massachusetts, the printers of the Boston Chronicle felt no such compunctions. On May 9, they published a fiery account of the Sparker killing, how it came about, and how the people of Newport had responded. However, their report also got some important details wrong:

We hear from Newport, that on Tuesday the 3d inst. about midnight a fray happened at a house of bad fame there, between some of the officers of the Senegal man of war on that station, one Nichols a Dutchman a shoemaker, and one Dexter a sailor, both belonging to Newport.

It began in the house with high words, during which Dexter put out the candle, and a scuffle ensuing one of the officers had his nose cut off, then Nichols and Dexter went away, and the people belonging to the man of war, went to a doctor’s.

Soon after their departure, it is said, Dexter having changed his dress, came back to the house with a club stuck with nails, threatening to search it, but on being answered they were not there, after some time departed, they however unluckily met again in the street, came to blows, when Nichols and Dexter were both run through the body—the Dutchman immediately ran home, called out that he was a gone man, and died in a few minutes. Dexter was alive when the post came away, but, it was thought could not long survive.

Next day an application being made to Capt. Cookson, of the Senegal, he expressed much sorrow for what had happened, accompanied the sheriff [Joseph G. Wanton] on board his ship, and delivered up his officers to the civil authority; a vast concourse of people attended their landing, and threatened to dispatch them; but by the prudent management of the sheriff, they were safely conducted to the court house, followed by the crowd, where they were examined, and afterwards committed to gaol [jail].

During the examination, several of the crowd behaved with such indecency to the judges, that they ordered the sheriff to carry them to gaol, but the mob prevented him from putting their orders in execution.

Neither of the Rhode Island newspapers had said anything about the establishment where the men first clashed, but the Boston paper declared right out that it was “a house of bad fame.” On top of that, the Boston Chronicle portrayed the Newport “mob” as threatening to “dispatch” or lynch the naval officers and showing disrespect toward the local sheriff and judges.

Yet the Chronicle account also said that the victim was a “Dutchman” (Dutch or German?) named Nichols instead of Sparker, and that the wounded man was a local instead of from Providence. So the out-of-colony newspaper’s account of the affair might have been distorted in other ways.

Still, decades later, when defying royal officials had become respectably patriotic, Rhode Island chroniclers looked back on the Sparker killing and linked it to the larger Revolutionary conflict. Wilkins Updike wrote in 1842 that the case “excited an intense interest growing out of the exasperated state of animosity existing between this country and Great Britain, respecting the Stamp act.”[3] That law had actually been repealed two years before, but there was ongoing friction in Newport over the impressment of sailors and the enforcement of customs laws. In that atmosphere, a Royal Navy officer killing a local man could be tied to the larger political conflict, even if it was just a street fight.

By the time any newspaper reported on the case, Midshipman Careless and his accused accomplices had filed their first legal motion. They petitioned the Rhode Island General Assembly to authorize the superior court to convene quickly. Ordinarily that court would not have sat until September. Indeed, the legislature did not even select five gentlemen to serve as superior court justices for the coming year until the day after the killing.[4]

Often defense attorneys try to delay trials until after public passions have cooled, but in this case the defendants were asking for a faster process. They argued that “His Majesty’s service,” meaning the Royal Navy, might “greatly suffer” if three of its officers were stuck in jail until September.[5] In response, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed “An Act empowering the justices of the superior court of judicature, court of assize and general jail delivery, to meet and hold a special court, for the trial of Thomas Careless, Charles John Marshall and Robert Young….”[6]

Careless must have felt confident about his claim of self-defense. In the petition to the General Assembly he stated that he and his naval comrades had been “assaulted…and knocked down” by Sparker, Dexter, Knap (the man who owned the house where Sparker died), and “one other person.” The midshipman said he had wielded his sword only to defend himself and his companions. He listed five members of the Senegal’s crew who could support that claim of self-defense.[7]

On June 1, slightly less than a month after the fatal fight, the special court session began. Chief Justice Joseph Russell presided, with justices Metcalf Bowler, William Greene, Nathaniel Searle, and Samuel Nightingale also sitting. Rhode Island attorney general Oliver Arnold prosecuted the naval officers on the charge of murder. It is not clear which lawyer handled the defense.[8]

The trial lasted three days. On June 6, Southwick’s Newport Mercury reported the result:

The Jury, consisting of Gentlemen of Capacity and undoubted Reputation, having heard the Case plead, with the Evidences and Circumstances attending the unhappy Affair, went out, and in a few Minutes returned to their Seats, and declared the Prisoners not Guilty, the Verdict being to the entire Satisfaction of the Court; and accordingly the Prisoners were immediately and honourably discharged.

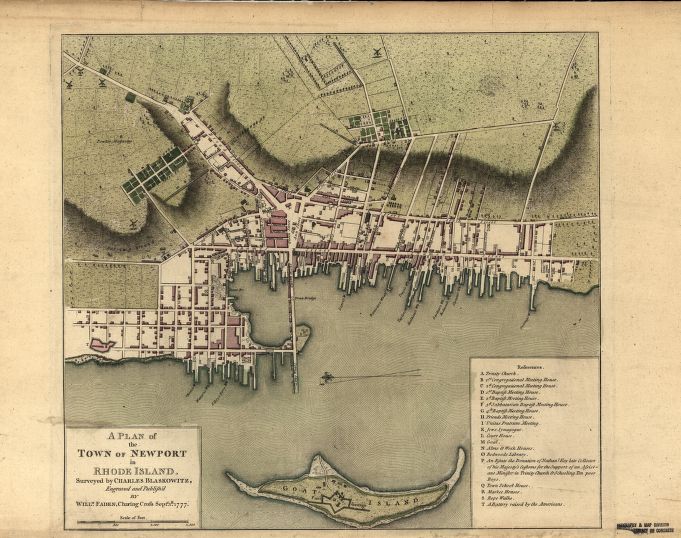

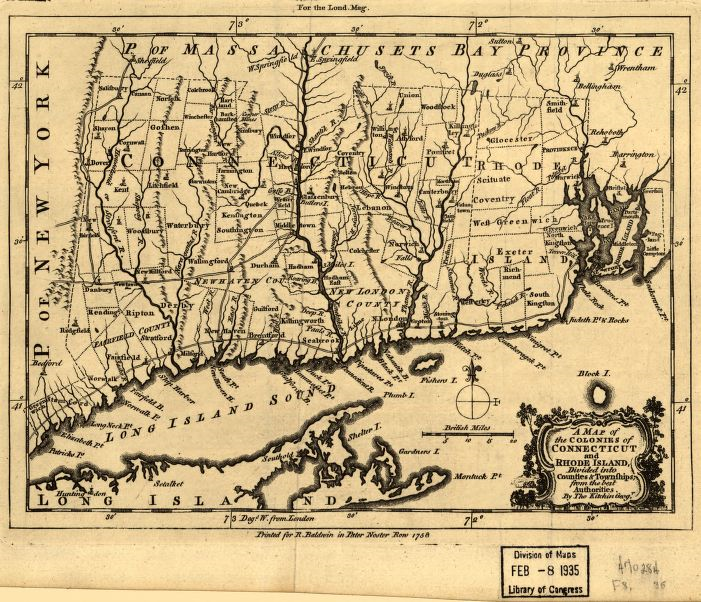

Connecticut and Rhode Island Colonies, 1758. Block Island is south of Rhode Island (Library of Congress)

N.B. Mr. Dexter, the other Person wounded, is now almost recovered: His Evidence was greatly in Favour of the Prisoners.

A month before, the Rhode Island newspapers had stated that Philip Dexter would probably soon die, leaving Midshipman Careless responsible for killing two local men. But Dexter had “almost recovered” and was healthy enough to testify. Indeed, the sailor’s testimony appears to have been the decisive evidence for acquittal. Dexter’s description of his own actions that night might have revealed that he had been the aggressor, as the Boston Chronicle had reported.

In his newspaper Southwick emphasized the jurors’ fine reputations and the appropriate verdict, once again highlighting Rhode Island’s respectability. If there was any loud objection to the acquittal of Midshipman Careless out on the streets, it never made the papers.

Young, Careless, and Marshall went back to their stations in the Royal Navy. Almost immediately the Senegal left Newport, sailing for Halifax.[9] In 1776 Careless was assigned to H.M.S. Eagle, the ship that carried Admiral Lord Richard Howe to North America as he took over command of the naval forces there.[10] The following June, his run-in with the law apparently having no negative impact with his superiors, Careless received a promotion to the rank of lieutenant.[11]

Careless and Rhode Island were not yet done with each other. In 1780 the lieutenant was serving on H.M.S. Royal Oak, part of the fleet of Vice Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot. A French fleet was inside Narragansett Bay, and Arbuthnot had his ships hover outside, hoping to bottle up the enemy. At one point the Royal Oak anchored off Block Island, part of Rhode Island but so vulnerable to passing warships that it had become neutral ground. The island was used by spies and smugglers, and British ships often sent squads ashore for fresh water.

A retired midshipman named Francis V. Vernon recalled Careless’s ill-fated interaction with a Block Island official—not a “governor,” as Vernon labeled him, but perhaps a local officeholder:

The inhabitants were disaffected; but being awed into an appearance of loyalty, their governor came to pay his respects to the Admiral, and on his return was accompanied by a Lieutenant Careless, in one of the Royal Oak’s boats. The governor thought he might now display his sentiments, and making some illiberal reflections against the British government, was seized by the Lieutenant and thrown into the sea. The boat was near land, and gave an opportunity to the governor to get on shore; who soon after, on making a complaint to the Admiral, occasioned a court-martial to be held on Lieutenant Careless.

The circumstance of throwing the governor overboard was clearly proved, which might have been pardoned, on considering that it proceeded from zeal to his Majesty’s service; but as Mr. Careless was fortunately for himself, an independent man, this counterbalanced every other excuse, and he was therefore dismissed the service.[12]

Lieutenant Thomas Careless’s naval career ended on July 28, 1780, slightly over twelve years since he had been acquitted of murder in Rhode Island.[13] Presumably he returned to Britain, but no evidence has turned up to show how he enjoyed his “independent” fortune there. Or whether he finally managed to keep away from more trouble.

[Banner Image: “A View of Part of the Town of Bostin in New England and British Ships of War Landing Their Troops!, 1768.” The Senegal is the vessel on the left with the number 2 written under it. Engraved by Paul Revere in 1770 (American Antiquarian Society)]

Notes:

For clarity, paragraph breaks have been added to the quotations from newspapers, and dashes have been converted to periods.

[1] The most thorough study of this incident using Rhode Island government sources is Kenneth Scott, “A Newport Street Fight in 1768,” Rhode Island History, vol. 18 (1959), 119-21. [2] Scott, “Newport Street Fight,” RIH, 18:120. Almost all American sources refer to the British midshipman as Careless; most, but not all, Royal Navy sources use the spelling Carless. In an eighteenth-century novel naming such a character Careless would be almost too blatant, but when that spelling is documented in real life it’s impossible to resist. [3] Wilkins Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode-Island Bar (Boston: Thomas H. Webb, 1842), 75. [4] Newport Mercury, May 9, 1768. [5] Scott, “Newport Street Fight,” RIH, 18:120. [6] Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, vol. 6 (1757-1769), John Russell Bartlett, editor (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1861), 544-5. [7] Scott, “Newport Street Fight,” RIH, 18:119-20. [8] Ibid., 121. [9] Ibid. [10] “Journals of Captain Henry Duncan,” John Knox Laughton, editor, The Naval Miscellany, vol. 1 (1902), 113. [11] David Syrett and R. L. DiNardo, editors, The Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy, 1660-1815 ([Aldershot]: Scolar Press for the Navy Records Society, 1994), 73. Thanks to Christian M. McBurney for supplying this source. [12] Francis V. Vernon, Voyages and Travels of a Sea Officer (London: [Wm. M’Kenzie], 1792), 34-5. It is possible that the Admiralty Office papers in the British National Archives contain a record of the Careless court-martial with more detail about what happened just off Block Island. [13] Syrett and DiNardo, Commissioned Sea Officers, 73.