This is the third article in a row providing book reviews of recent Rhode Island history books. Surprisingly, each of the three books here is a historical novel that has the American Revolutionary War and slavery in Rhode Island as the backdrop. The latter two, specifically, have Newport as the backdrop. The first book, by James Glickman, who currently teaches writing at the Community College of Rhode Island, enjoyed a coup recently, a favorable review in the Wall Street Journal.

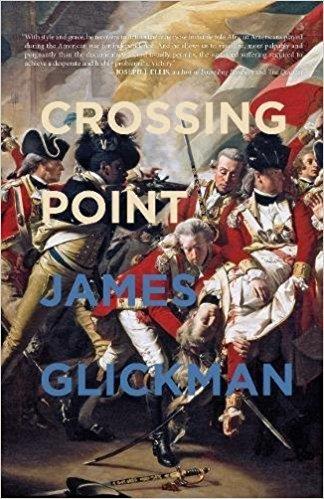

James Glickman, Crossing Point (Rare Bird Books, 2017) (448 pages) ($17.95 (currently $12.16 on amazon.com) paperback).

Glickman makes two terrific decisions in choosing his two main characters. First, he chooses Samuel Ward, a young gentleman on the make from Westerly determined to mark his service in the First Rhode Island Regiment with military glory and honor. Through the youthful major, we follow the First Rhode Island Regiment as it joins George Washington’s newly-formed Continental Army outside Boston, makes its treacherous trek through the woods of Maine and to the gates of Quebec, and puts up an incredibly stout defense of Forts Mercer and Mifflin on the banks of the Delaware River outside Philadelphia. Sammy’s courtship with Phebe Greene, the daughter of a future state governor, also rings true. Interspersed in the book are major historical figures, such as Ward’s friend, Major Nathanael Greene of East Greenwich, and many minor figures from Rhode Island’s revolutionary era who are worth remembering.

His second decision was even better, focusing on Guy Watson, an enslaved man to the Hazzard (yes with two z’s) family in South Kingstown. In real life, Guy Watson, a South Kingstown resident, served honorably in the First Rhode Island Regiment, when its ranks were first opened to Rhode Island slaves and other persons of color, in exchange for granting slaves their freedom. Even as late as the 1830s, as one of the last surviving veterans of the war and one if the famed “Black Regiment,” he was feted at July 4th parades in Providence. In this book, Watson decides to enlist in the First Rhode Island Regiment, hoping that one day soon after the war he could purchase his wife June and their first child, still enslaved by the Hazzards. Glickman brings to life the experiences and feelings of enslaved persons by having them meet without any whites around. His book is an excellent way to learn about Rhode Island’s role in the Revolutionary War in general, and the role of the extraordinary slaves who gained their freedom in return for risking their lives by serving in the First Rhode Island Regiment for the duration of the war. The book nears its end with Samuel Ward and Guy Watson fighting side-by-side at the Battle of Rhode Island at the north end of Aquidneck Island in August 1778. It concludes with a tension-filled court martial with the fate of Guy Watson and the son of his master at stake.

As a close student of Rhode Island in the Revolutionary War, I did notice several minor factual errors. The author would have done well to have read my authoritative books on the Battle of Rhode Island and the capture of General Richard Prescott at Portsmouth (The Rhode Island Campaign and Kidnapping the Enemy). He might have understood the difference between Kingston and South Kingstown, and that the village of Kingston had its name changed from Little Rest in 1825, if he had read my History of Kingston (to be fair, many Rhode Islanders get confused on that score). And if he had read Robert Geake’s recent book on the First Rhode Island Regiment, the author likely would have added to the book soldiers in the regiment who were members of the Narragansett tribe or of mixed African-American and Narragansett heritage. But these are only minor quibbles. This is good history well written.

To purchase the book or visit Glickman’s website, go to:

https://www.amazon.com/Crossing-Point-James-Glickman/dp/1945572426

https://www.amazon.com/James-Glickman/e/B0759R953S/ref=sr_tc_2_0?qid=1512743146&sr=1-2-ent

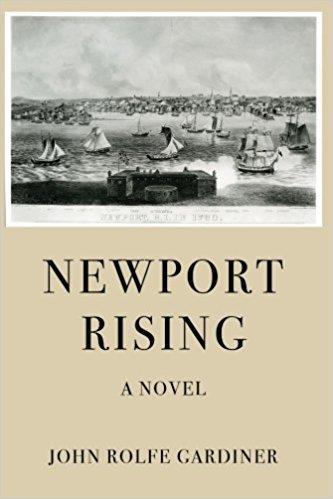

John Gardiner, Newport Rising, A Novel (Strafford & Unison, 2017) ($14.00 paperback). The protagonist of this novel, set in Newport in the period prior to and during the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, is journeyman typesetter Cotton Palmer, who occasionally pens political essays that cause him trouble. In Newport, he finds himself allied with several outcasts—Sally, an unmarried woman of questionable repute but with a strong personality and is a secret abolitionist; her mercurial brother, a skilled shipbuilder at Warren; and several slaves whom they befriend. They form an unlikely ring intent on upsetting the status quo in Revolutionary Newport. Real historical characters in the novel include the colorful Reverend Ezra Stiles of the Second Congregational Church, Quaker furniture-maker Job Townsend, and newspaper publisher Solomon Southwick. John Gardiner is a talented fiction writer and the book makes for interesting reading, though the reader does have to concentrate. The characters are compelling and it is a good story about pre-revolutionary and revolutionary Newport. But I wish the author had paid more attention to getting the port’s Revolutionary War history correct and interspersed with the novel’s story.

To learn more about this book or to purchase it, go to:

https://www.amazon.com/Newport-Rising-John-Rolfe-Gardiner/dp/069283981X

http://johnrolfegardiner.com/product/newport-rising/

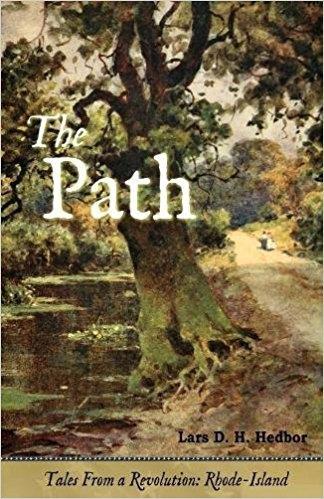

Lars D. H. Hedbor, The Path: Tales from a Revolution: Rhode Island (Brief Candle Press, 2017) (212 pages) ($12.99 paperback). Told from the point of view of an ordinary French soldier who embarks on board a French warship as part of French general Comte de Rochambeau’s expedition to North America to assist the Americans in their war for independence against Great Britain, the soldier lands in Newport in July 1780. Yves de Bourganes sought only some money to give to his mother, and perhaps experience an adventure, but he never expected to become enmeshed in a war between Great Britain and her rebellious colonies, far from the shores of his birth. It is when he encounters Amalie, an enslaved Newport woman with a difficult past, though, that his world is truly turned upside down. This novel does not develop as interesting characters as the other two, and the author shows little grasp of the geography of Aquidneck Island and Narragansett Bay or the military events that occurred there during the French occupation of Newport starting in July 1780. It is most interesting in its depictions of an ordinary French seaman, describing his motivations for joining the French Navy, his difficult life on board a French warship making an Atlantic Ocean crossing, and his landing in a strange land. It is also worth reading about the French soldier’s stay in the simple home of an abolitionist Quaker on the mainland.

To learn more about this book or to purchase it, go to:

Note on Slavery in Rhode Island. Given that Rhode Island’s history of slavery and participation in the slave trade is understandably a sensitive issue, I was curious how each book addressed the issue. At the time of the start of the Revolutionary War, Rhode Island had the highest percentage of slaves of any colony in New England (about 6 percent), due in large part to Newport merchants dominating the African slave trade among all North American merchants. None of the novels addresses in detail the slave trade, a much more difficult topic to deal with.

All three books refer to slave auctions occurring in Newport during the Revolutionary War years from 1775 to 1783. Hedbor’s book does have Amalie briefly describe her journey in the lower hold of a slave ship from Guadeloupe in the Caribbean, ending up being sold at a slave auction occurring in Newport, apparently while the British occupied the port from 1776 to 1779.

Hedbor has the French soldier saying that slave auctions were regular events in Newport in 1781 and 1782. Glickman’s and Gardiner’s books also mention slave auctions occurring in Newport during the war. However, my research indicates that the last slave auction in Newport occurred in the mid-1760s. In addition, there is no known record of either Newport or any other Rhode Island port sending out any slave ships to Africa during the Revolutionary War. (After the war, Bristol’s de Wolf family dominated the trade). Still, slave auctions did occur in Newport in colonial times, so novelists should therefore have some license on the matter.

I think Glickman’s book handles slavery the best. While the white masters, such as the Hazzards, are clearly the bosses in the relationship and could invoke terror to enforce their will, most times whites and blacks converse with each other on a relatively level playing field. Indeed, at times, the white masters have to negotiate with their enslaved persons to try to get their way. I believe this is an accurate portrayal for Rhode Island slavery. In Virginia and South Carolina, plantations sometimes had large numbers of slaves supervised by paid white overseers who, fearing insurrections, could often be cruel. In Rhode Island few farms had as many as five or even ten enslaved persons, so no overseers were hired and instead white masters dealt directly with their slaves, and often worked side-by-side with them.