Here is my list of the greatest Rhode Islanders of all time, numbers ten to six. In my last two articles, I counted down from numbers twenty to eleven, and also listed honorable mentions and current Rhode Islanders to watch. Next week I will reveal my top five.

Rhode Islanders can be proud of this top ten and twenty list. I am safe in saying that this list is more impressive than that of any other small or lightly populated state in the country, and is more impressive than many of the medium-sized and large states. Small state big history indeed!

Next week I will present some of the lists I created that influenced my decisions.

10. H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937)

Born Howard Phillips Lovecraft in Providence, he had a difficult childhood. His father suffered from a mental disorder caused by untreated syphilis and was committed to Butler Hospital in Providence. Lovecraft attended Hope High School, but suffered a nervous breakdown before he could graduate. Reading Edgar Allen Poe, he developed an interest in fantastical horror stories and ultimately became a master writer of the craft. After spending several years in New York City, including having a failed marriage, he returned to Providence in 1926, where he wrote most of his best work, including the short stories “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Colour Out of Space,” and the short novel The Case of Charles Dexter. He lived at 10 Barnes Street north of Brown University until 1933. Virtually unknown in his lifetime and barely able to survive on his writings in his later years before dying of cancer in Providence, since his death he has earned great acclaim and has inspired new generations of horror and fantasy fiction writers. The great horror fiction writer Stephen King wrote of him in American Heritage magazine, “Now that time has given us some perspective, I think it is beyond doubt that H.P. Lovecraft has yet to be surpassed as the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.” What you can see now: his house at 33 Barnes Street, a stop on organized Lovecraft walking tours of Providence, which are frequent. For further reading: Lovecraft’s works remain in print in a variety of forms.

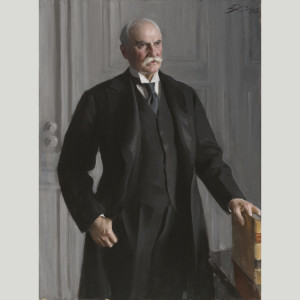

9. Nelson W. Aldrich (1851-1915)

Born in a farmhouse in Foster, he was the son of a mill worker and his first job was as a grocery clerk in Providence. After serving briefly in the Union Army in the Civil War, he rose in politics in the state Republican Party. The General Assembly elected him to the U.S. Senate in 1881 and he held that seat for thirty years, winding up as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. He became the state’s most powerful politician ever to serve in the nation’s capital. In an age of weak presidents, Aldrich led a small coterie of Congressional leaders, becoming known as “the political boss of the United States” and “the general manager of the U.S.” He represented conservative business interests, including those on Wall Street and the sugar trust looking for government privileges. While he believed that America was best when big business and government worked together, he was fiercely criticized by progressives. Strongly opposing the income tax, he instead designed a tariff bill that increased tariff rates, which benefitted Rhode Island’s textile and other factories, helping them pay their workers high wages, but it hurt consumers and farmers, and caused a backlash in Congress. As a compromise, he allowed submitting to the states for ratification a constitutional amendment providing Congress with the power to levy income taxes, which he expected to fail, but to his dismay passed in 1913. His greatest achievement was being one of the driving forces to establish the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913, thereby finally modernizing America’s financial system. Since the Great Depression, the Federal Reserve Bank has helped to minimize the impact of economic downturns. He became fabulously wealthy after borrowing funds from sugar trust companies and investing in Rhode Island trolley lines. With his new money, he built a 99-room chateau at Warwick Neck on Narragansett Bay and acquired a 200-foot yacht. His daughter, Abbey, raised and educated in Providence, in 1901 married one of the world’s richest men, John D. Rockefeller, and became a renown philanthropist, including being the primary founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. What you can see today: the Nelson W. Aldrich House is a Federal-style house at 110 Benevolent Street in Providence , Aldrich’s home from 1881 to 1911; it is now held by the Rhode Island Historical Society. For further reading: Roger Lowenstein, America’s Bank. The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve (Penguin, 2015).

8. John E. Fogarty (1913-1967)

Born into an Irish Catholic family in Providence in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood, he attended LaSalle Academy before being forced by the Great Depression to put his studies aside and work as a bricklayer. In 1939 he rose to become president of Bricklayers Union No. 1 of Rhode Island. Elected to the U.S. Congress at the age of just twenty-seven in 1940, he resigned on December 4, 1944, to enlist in the U.S. Navy. He was reelected to the House and served Rhode Island in that capacity from 1945 until his death. In 1949, he was appointed Chairman of the Subcommittee on Labor, Health, Education and Welfare. This union leader and New Deal Democrat suddenly became one of Congress’s all-time champions of medical research and public health. During his time in Congress, subcommittee chairs had much more power than they do currently. At his insistence, funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which now supports most of the nation’s biomedical research, increased from $26.5 million in 1948 to $1.24 billion in 1967, which was a tremendous amount back then. He firmly believed that dollars spent for medical research would ultimately save many more dollars later in medical care and save more lives. His compassion showed in bills that he sponsored for persons who were mentally disabled, physically disabled, deaf and blind. He became known as the “Champion of Better Health for the Nation” and “Mr. Public Health.” He was also a key sponsor for legislation promoting libraries and for establishing the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities. In 1964, he established the John E. Fogarty Foundation for Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, which continues its work today. Despite his focus on national health issues, he was known as “Everybody’s Congressman” and was popular in his home state. Working closely with all U.S. presidents during his tenure as chairman, he was the state’s most influential member of the House of Representatives in its history. The Historian Laureate of Rhode Island, Patrick T. Conley, wrote of Fogarty, “He was the Ocean State’s most productive congressmen yet, and had more impact on the world than any other Rhode Island political figure because of his path-breaking health initiatives.” A fellow congressman, Philip Philbin of Massachusetts, said of him, “It can be said without fear of contradiction . . . that John Fogarty is the greatest political health leader in our nation’s history.” Unfortunately, his own health was poor and he died of a heart attack at the age of only fifty-three as he was being sworn in for his fourteenth term on January 10, 1967. In his memory, the Fogarty International Center was created at NIH, which continues to train doctors worldwide and work in more than 100 countries. Four health and educational facilities are named after him in Rhode Island. What you can read today: Patrick T. Conley’s remembrance, originally published in the Providence Journal on March 26, 2013, at www.fogartyfoundation.org (type in Google “John E. Fogarty” and “Patrick T. Conley”). Conley will also include a chapter on Fogarty in his upcoming book, Rambles Through Rhode Island and Beyond, to be published by the Rhode Island Publications Society.

7. Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910)

Julia Ward Howe, author, poet, lecturer, and women’s club and rights organizer, is best known for writing the Civil War anthem, “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and co-founding the American Woman Suffrage Association with Lucy Stone. Her father was a wealthy New York City banker, Samuel Ward, whose grandfather was one of Rhode Island’s signers of the Declaration of Independence and whose father was a distinguished Revolutionary War officer from Rhode Island (both also bearing the name of Samuel Ward). Her mother died when she was five. She was educated primarily by tutors at her New York City home. Despite their eighteen-year age difference, in 1843 she married the dashing Samuel Gridley Howe, who had gained some fame fighting in Greece’s struggle for independence from Turkey and as the head of a Massachusetts school for blind children. While they had six children together, their marriage was not a happy one, as a result of Samuel insisting that Julia keep to the domestic sphere and trying to prevent her from achieving the greatness that she sought. While the couple lived in Boston, they summered at Newport and Portsmouth. In 1852, for example, they summered in Newport with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his wife. In 1862, Atlantic Monthly published “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which brought her lasting fame. A favorite of Abraham Lincoln’s, it framed the Civil War and freeing the slaves in the South as a Christian crusade. Finding her place in the women’s movement, she helped establish the New England Women’s Club, the American Woman Suffrage Association (1868), the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, the New England Suffrage Association (1868), and the Association for the Advancement of Women (1873). In the late 1870s, Howe conducted speaking tours in the Midwest, Europe, and the Middle East, calling for a peace movement in response to the Franco-Prussian War and attending a Woman’s Peace Conference in London. In 1871, the Howes purchased a summer cottage in Portsmouth. Her husband died in 1876, with much of her inheritance lost by him through poor investments. In 1886, she moved to a larger abode called Glen Oak on Union Avenue in Portsmouth and stayed there for a good portion of the remainder of her life. She served as the President of the American Woman Suffrage Association until 1877 and again from 1893 to 1910; she presided over the New England Suffrage Association from 1870 to 1878; and she served as Director of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in the 1890s. At a meeting of the New England Woman Suffrage Association in 1887 at the Newport Casino, she and Susan B. Anthony were the keynote speakers. Beloved by many, the snowy-haired Ward lectured widely and traveled the country, but also spoke at churches in Newport, Portsmouth, and Tiverton. In 1908, Howe became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She also received an honorary degree from Brown University. She died of pneumonia in 1910 at age 91 at Glen Oak in Portsmouth. Her daughter, Maud Howe Elliot, was a writer and founded the Newport Art Association, which became the Newport Art Museum. For further reading, see Elaine Showalter, The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

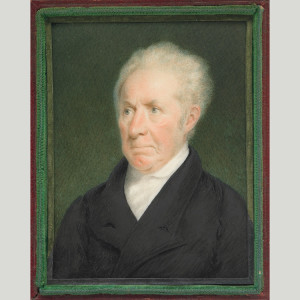

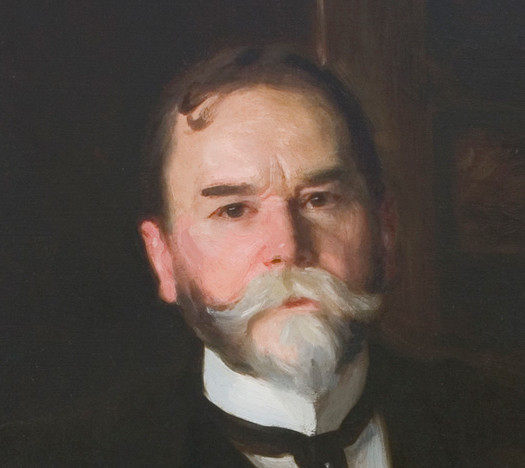

6. Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828)

Born in North Kingstown to a Scottish immigrant who built the first snuff mill in the thirteen North American colonies, Stuart and his family moved to Newport when he was age six. In 1769, when he was thirteen or fourteen, Stuart was tutored by Scottish artist Cosmo Alexander and painted Dr. Hunter’s Spaniels, which can be seen today at Newport’s Hunter House. Alexander took Stuart to Scotland the next year, but then Alexander died. Stuart returned to Newport, probably in late 1773, and stayed until September 1775. In that period he honed his craft, painting several portraits that hang at the Redwood Library& Athenaeum, including Christian Banister and Son. He then studied in London under American painter Benjamin West, culminating in his painting The Skater in 1782, in which a skater glides across the ice. He became perhaps America’s foremost painter of portraits. He is best known for his unfinished 1796 Athenaeum portrait of George Washington, which is still shown on the U.S. one dollar bill and hangs at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. His Lansdowne portrait of Washington hangs in the East Room of the White House. Most state capitols have a copy of a Stuart portrait of Washington hanging in them. In 1801, the Rhode Island House of Representatives commissioned Stuart to provide two full-scale portraits of Washington; one now hangs in the Rhode Island State House in Providence, and the other in the Old Colony House in Newport. Traveling throughout the nation, Stuart painted more than one thousand portraits, including six presidents. His portrait of an elderly John Adams in the last year of his life, now hanging in the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., is particularly endearing. His pieces are currently held by most of the major fine art museums in the U.S. Stuart died in Boston, where he lived for many years. His daughter Jane had a studio in Newport, from which she painted and sold excellent copies of his paintings, as well as her own fine works. What you can see today: The Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum, including a snuff mill, in North Kingstown. For further reading: Dorinda Evans, The Genius of Gilbert Stuart (Princeton University Press, 1999).

[Banner image: Miniature of Gilbert Stuart by Sarah Goodridge of Boston around 1825 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)