In the last three weeks, I gave you my list of the top fifteen greatest Rhode Islanders of all time. The following famous Rhode Islanders fill out my top five (there is one tie, making six in all).

Rhode Islanders can be proud of this top twenty list. I am safe in saying that this list is more impressive than that of any other small or lightly populated state in the country, and is more impressive than many of the medium-sized and large states. For example, I believe the list is more impressive than those for nine of the original thirteen states (New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut (yes!), New Jersey (again, yes!), Maryland, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, and let’s throw in Vermont), is as strong as one for Pennsylvania, and is only overshadowed by those of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. Small state big history indeed!

At the end of this article are some lists that I relied on in part in making my selections. For the criteria that I used, see the ends of the articles for Counting Down from Number 15 to 11 and Counting Down from Number 20 to 16. Those two articles also contain the up-to-date lists of honorable mentions and current Rhode Islanders to watch.

At the end of this article is a brief explanation of the criteria I used.

5. Metacomet (King Philip) (ca. 1638-1676)

He was the son of Massassoit, the chief sachem of the Wampanoag tribe whose lands encompassed much of the east bay lands of Rhode Island, as well as southeastern Massachusetts. Massasoit befriended both the Pilgrims when they settled at Plymouth in 1620 and later Roger Williams at Providence. Metacomet (or Metacom), or King Philip as he became better known among whites, became chief sachem of the Wampanoags in 1663, after his father died the prior year and his older brother then died under mysterious circumstances when in the custody of Pilgrim authorities. He maintained his tribal seat at Mount Hope in Bristol, Rhode Island. Relations with the Pilgrims soured as white settlers expanded onto his tribe’s lands and Pilgrim courts dealt with Metacomet in disrespectful ways. In June of 1675, the charismatic sachem persuaded several New England tribes to rise up in a bloody war against Puritan and Pilgrim Massachusetts. While scoring early successes, Indian warriors and their families eventually suffered devastating losses, including the defeat of the Narragansetts at the Great Swamp in South Kingstown in December 1675. The war ended with the hunting down and killing of Metacomet in August of 1676 at Mount Hope, by a force commanded by Captain Benjamin Church of Little Compton. The war was named after the sachem: King Philip’s War. In terms of the percentage of deaths of population, King Philip’s War was the bloodiest war in American history, and it ended forever the power of the Native Americans in southern New England. What you can see today: King Philip’s Seat at Mount Hope in Bristol, on grounds off Tower Street managed by the Mount Hope Trust. For further reading: Nathaniel Philbrick, Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War (Penguin, 2006).

4b. Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858)

Born in Newport, he became a career naval officer, sailing under the command of his younger brother, Oliver Hazard Perry, before serving in the War of 1812 and the Barbary War. In 1837 he commanded the U.S. Navy’s first steam-powered warship, the USS Fulton, and organized the first U.S. Naval Engineer Corps. He is considered the father of the U.S. steam navy. He commanded the Home Squadron off the east coast of Mexico in 1847-48 during the Mexican War. He won recognition as a reformer in naval education, training for recruits, and steam engineering. He helped establish the curriculum at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis and many of his ideas were taught at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport. Most famously, under orders from President Millard Fillmore, he commanded a U.S. naval expedition to Japan on two visits in 1853 and 1854 that opened U.S. trade with Japan, which prior to then had isolated itself from the outside world for nearly 250 years. Perry proved that the Shogun, Japan’s hereditary military dictator, could not enforce Japan’s isolationist policy; this led to the collapse of the shogunate and ultimately to the modernization of Japan. On his return to the U.S., Congress awarded him $20,000 (about $500,000 in today’s currency). Shortly after completing a three-volume work on his expedition to Japan, he died at age sixty-four. His remains were moved from New York City to Newport in 1866; he and his famous brother are interred at Newport’s Island Cemetery. Perry Park in Kurihama, Japan, a monolith monument to the landing of Perry’s forces, has a small museum dedicated to the 1854 events. What you can also see today: a nice exhibit on his service at the Naval War College Museum in Newport, including a bust. For further reading: John H. Schroeder, Matthew Calbraith Perry: Antebellum Sailor and Diplomat (Naval Institute Press, 2001).

4a. Oliver Hazard Perry (1785-1819)

His father, Christopher Raymond Perry, when he was a prisoner-of-war held in Ireland during the American Revolutionary War, met a spirited Scotch-Irish woman, Sarah Wallace Alexander, a descendant of the Scottish warrior William Wallace, and later married her and brought her to his home in Rhode Island. Born in South Kingstown, Oliver Hazard Perry was their eldest child and moved with his family to Newport around 1793. He became a midshipman on his father’s ship attacking French commerce during the quasi-war with France in 1799 and 1800. Strikingly handsome, he married Elizabeth Champlin Mason in Newport in 1811. During the War of 1812, the British and Americans fought for command of the Northwest Territory around the Great Lakes. Only twenty-eight years old and a mere lieutenant, Perry was sent from his post at Fort Adams in Newport to Lake Erie to supervise the construction of a small American naval fleet at Presque Isle Bay, Pennsylvania. More than 150 Rhode Island sailors volunteered to help man the fleet, a testament to the loyalty he inspired. On September 13, 1813, Perry commanded the fleet, boldly attacking the Royal Navy fleet on Lake Erie. His flagship Lawrence, which aptly carried a flag with “Don’t Give Up the Ship” emblazoned on it, at one point desperately fought the British virtually solo. With all of the officers on his shattered ship either killed or wounded, except Perry and his younger brother, he was rowed to the Niagara, after which he completed a stunning victory, capturing all of the enemy ships. His brief but memorable words after the battle were, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” He then cooperated with General William Henry Harrison’s army in retaking Detroit. These were key strategic victories for the United States , which allowed it to keep territory in post-war negotiations. Prior to the battle, he described his crews as “a motley set of blacks, soldiers, and boys.” But after the battle he spoke “highly of the bravery and good conduct of the negroes, who formed a considerable part of his crew. They seemed to be absolutely insensible to danger.” Back in Newport, hearing about a shipwreck off Point Judith, he personally led a whaleboat into a storm to rescue eleven survivors. In 1816 and 1817, he commanded a U.S. frigate against Barbary pirates operating in North Africa, where in the end he conducted successful diplomatic negotiations without resorting to combat. While on a diplomatic mission in Venezuela in 1819, he contracted yellow fever and died shortly thereafter on this thirty-fourth birthday. His body was disinterred at Trinidad and returned to Newport in 1826, where the city held the most elaborate funeral service in its history. He was reinterred at Island Cemetery in 1841, when the state paid for a granite monument to him. Many localities are named after him throughout the country, including ten Perry counties. Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial, located at Put-in-Bay, Ohio, is a 352-foot tall memorial overlooking Lake Erie celebrating Perry’s victory and peace with Canada. What you can also see today: a nice exhibit on his service, including a painting and bust of him, at the Naval War College Museum in Newport. His wife put up a memorial plaque honoring him in Trinity Church. For further reading: David Curtis Skaggs, Oliver Hazard Perry: Honor, Courage and Patriotism in the Early U.S. Navy (Naval Institute Press, 2006).

3. Samuel Slater (1768-1835)

At age fourteen he began a seven-year management apprenticeship at Jedidiah Strutt’s mill in England, which used the latest water-powered mill machines designed by Richard Arkwright to spin cotton. Leaving for America in 1789, he moved to Rhode Island, lured by financing offered by Moses Brown of Providence. Slater began work in Pawtucket (then part of North Providence) at Carpenter’s Fulling Mill, which Brown had rented in order to collect and further develop the most recent experimental spinning and carding machines of the day. Slater improved those designs, and in some cases started from scratch with new designs, with the assistance of local mechanics Sylvanus Brown and David and Oziel Wilkinson. After that mill began operating in December 1790, the same investors, led by Moses Brown and including Slater, built a new cotton mill nearby at what is now Slater Mill, powered by water flowing from the Blackstone River. Slater’s machines produced the first cotton thread in August of 1793 and Slater Mill became the first successful water-powered cotton-spinning factory in North America. Five years later, Slater partnered with the Wilkinsons to build across the river White Mill, which became the inspiration for other mills, first throughout the Blackstone Valley and eventually all over New England. In 1803 Slater and his brother John built a mill village in North Smithfield they called Slatersville (now an historic district). Slater developed the “Rhode Island System,” in which entire families, including women and children, were hired, and often lived in company housing, shopped in the company store, and attended company schools. Slater is considered the father of American industry; President Andrew Jackson called him, “the father of American Manufactures.” Rare for an inventor, he became wealthy as a result of his businesses. He spent a considerable amount of time in Rhode Island, after marrying in 1791 Hannah Wilkinson of Pawtucket, who invented a type of cotton sewing thread and in 1793 at the age of nineteen became the first American woman to be granted a patent. What you can see today: The Slater Mill Historic Site at Pawtucket, one of the state’s leading historical sites and birthplace of the American industrial revolution. For further reading: Barbara Tucker, Samuel Slater and the Origins of the American Textile Industry, 1790-1860 (Cornell University Press, 1984).

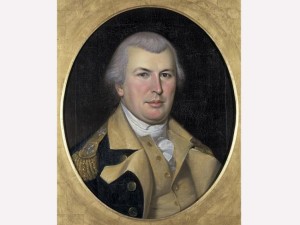

2. Nathanael Greene (1742-1786)

Nathanael Greene in his Continental army uniform, by Charles Wilson Peale, c. 1794 (National Historic Independence Hall Collection)

Born in Warwick into a Quaker family, he read military history on his own but was rebuffed from becoming an officer in East Greenwich’s Kentish Guards due to a limp he had developed from a childhood injury. Still, after the Revolutionary War broke out at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the Rhode Island government recognized his future promise and put him forward as its leading military commander. Greene quickly rose to become a major general in the Continental Army. Impressed by Greene’s sound judgment, General George Washington decided that if he died he wanted Greene to replace him as commander-in-chief. During the crucial winter at Valley Forge, Washington asked him to serve as quartermaster general to feed and clothe the troops to the extent possible, which Greene did brilliantly. In August 1778 he served on Aquidneck Island, helping to repel a British attack. Greene was probably the best military strategist of the war on either side. From December 1780 to June 1781, he led the undermanned southern army in a brilliant campaign against a more powerful British army led by General Charles Cornwallis. Greene’s army was defeated on several occasions, yet would rise again and again, and outmaneuver Cornwallis. He excelled at dividing, eluding and tiring his opponents by long marches. Ultimately, his army gained control of most of the South and Cornwallis’s exhausted army was captured at Yorktown, Virginia in October of 1781. Married to the vivacious and intelligent Catharine Littlefield of Block Island, Greene tragically died of heatstroke at the age of forty-four, while working on the plantation in Georgia granted to him by that state. What you can see today: the Major General Nathanael Greene Homestead, built by Greene in 1770, in Coventry at 50 Taft Street, and open to the public. For further reading: Gerald M. Carbone, Nathaniel Greene: A Biography of the American Revolution (Palgrave MacMillan, 2008).

1. Roger Williams (ca. 1603-1683)

Born in London, England and becoming a clergyman, he is considered the founder of Rhode Island. In January 1636 he fled persecution by Puritan authorities in Massachusetts and, a few months later, settled, with a few of his followers, on land peacefully acquired from Native Americans. He named the new settlement Providence. He also founded the first Baptist Church congregation in America in 1638 and 1639, even though he spent most of the rest of his life not affiliated with any formal church. Travelling back to England in 1643, he used his influence with top Puritan officials to obtain a charter bringing together Providence with two other havens from persecution by Puritan Massachusetts—Newport and Portsmouth—thereby securing the colony’s separate legal existence. While in England, he wrote influential pamphlets advocating freedom of conscience and separation of church and state, and practiced it in Rhode Island, thereby anticipating, by about 150 years, the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. His stance was remarkable, in an age when practically every country had a policy of imposing its established religion on others. In 1663, Dr. John Clarke of Newport built on Williams’s vision by obtaining a royal patent securing freedom of religion and separation of church and state in Rhode Island, as well as protecting it from encroachments by Massachusetts and Connecticut. Williams was fair to the Indians he dealt with and he wrote a book on the language and culture of the Narragansett tribe, the first published anthropological study of Native Americans in North America. The Indian-white alliances he wrought fell apart during King Philip’s War, with Narragansett warriors burning Providence, but they spared the lives of Williams and his fellow settlers. Roger Williams University in Bristol and Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence are named after him. What you can see today: Roger Williams National Memorial at 282 North Main Street, where Williams laid out his first settlement in Providence, now a federal park with a visitor’s center. For further reading: John M. Barry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul. Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty (Viking, 2009) and Alan E. Johnson, The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience (Philosophia Publications, 2015).

[Banner Image: U.S. stamp celebrating the 200th anniversary of Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813]In preparing my list, I relied in part on the following lists that I created.

Prominent Statues of Rhode Islanders

- Nathanael Greene, National Hall of Statuary, U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C. (first statue placed in Statuary Hall, in 1872)

- Roger Williams, National Hall of Statuary, U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C.

- Nathanael Greene, south side of Rhode Island State Capitol (right side of steps)

- Oliver Hazard Perry, south side of Rhode Island State Capitol (left side of steps)

- Roger Williams, Prospect Park, Providence

- Thomas Wilson Dorr, outside entrance to State Senate

- William Ellery Channing, Boston Public Garden

- Oliver Hazard Perry, Eisenhower Park, Newport

- Ambrose Burnside, Burnside (formerly City Hall) Park, Providence

- Esek Hopkins, Hopkins Square, corner of Charles Street and Branch Avenue, Providence

- Matthew Calbraith Perry, Touro Park, Newport

- William Ellery Channing, Touro Park, Newport

- Christina Bannister (organizer with African-American and Narragansett Indian heritage), inside the Rhode Island State Capitol

- J. Howard McGrath, Rhode Island governor, U.S. senator, and U.S. Attorney General, inside the Rhode Island State Capitol

- Dr. John Clarke, who obtained a key charter for Rhode Island in 1663, Memorial Boulevard, Newport

- Ebenezer Knight Dexter, early philanthropist, Dexter Training Grounds, Cranston

- Ninigret, sachem, Watch Hill, Westerly

- Mayor Thomas A. Doyle, corner of Broad and Chestnut Streets, Providence

- Monsignor Galliano Cavallaro, Atwells and Dean Streets, Federal Hill, Providence

- Canonchet, Narragansett sachem, Narragansett Beach, Narragansett

United States Postage Stamps with Rhode Islanders Appearing on Them

- Oliver Hazard Perry, 1870-90

- Roger Williams, 1936

- Nathanael Greene (and George Washington), 1936

- Gilbert Stuart, 1940

- Matthew Calbraith Perry (opening of Japan), 1953

- Nathanael Greene (Battle of Eutaw Springs), 1981

- Julia Ward Howe, 1987

- Roger Williams (settling of Rhode Island), 1986

- Samuel Slater (Slater Mill Historic Site; Slater not shown), 1990

- Oliver Hazard Perry (Battle of Lake Erie), 2013

Number of Words Written about Rhode Islanders in the Dictionary of American History, Stanley I. Kutler (editor), ten volumes, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2001-2003

- Roger Williams—318

- Nathanael Greene—311

- Ambrose Burnside—214

- Samuel Slater—179

- Oliver Hazard Perry—161

- Matthew Calbraith Perry—148

- Julia Ward Howe—97

- Metacomet (King Philip)—88

- Thomas Wilson Dorr—66

- Robert Gray—63

- Samuel Hopkins—34

- Mary Dyer—27

- Gilbert Stuart—16

- Theodore Francis Greene—15

- Nelson W. Aldrich—14

- George Corliss—12

A Separate Biographical Entry is in the Oxford Companion to United States History (London: Oxford University Press, 2001) for these Rhode Islanders:

Roger Williams, Nathanael Greene, and Oliver Hazard and Matthew Calbraith Perry

Number of Hits When the Rhode Islander’s Name is Searched in Google in Quotation Marks, with “Rhode Island,” on Nov. 9, 2015 (the next number is the number of hits when the name is searched in Google without the term “Rhode Island,” which in cases of common names can pick up unrelated persons)

- Roger Williams—528,000 (3,550,000)

- King Philip—140,000 (587,000)

- Nathanael Greene—94,400 (377,000)

- H.P. Lovecraft—79,900 (527,000)

- Theodore Francis Greene—74,300 (285,000) [airport named after him]

- Ninigret—69,900 (122,000) [some local places include his name]

- Gilbert Stuart—66,000 (400,000)

- Stephen Hopkins—57,100 (398,000

- Oliver Hazard Perry—48,300 (378,000)

- John Clarke—52,600 (473,000) [very common name]

- Claiborne Pell—47,100 (105,000)

- Samuel Slater—45,000 (127,000)

- Robert Gray—41,300 (435,000) [very common name]

- Canochet—31,000 (55,000) [some local places include his name]

- Royal Little—27,200 (110,000)

- John Chafee—27,200 (60,100)

- Canonicus—25,300 (353,000)

- Julia Ward Howe—20,600 (325,000)

- Mary Dyer—18,000 (136,000)

- Samuel Hopkins—18,100 (170,000)

- John La Farge—17,600 (161,000)

- Nelson Aldrich—17,400 (68,400)

- Ambrose Burnside—16,300 (110,000)

- William Ellery Channing—12,400 (259,000)

- Howard McGrath—12,000 (58,200)

- Thomas Wilson Dorr—10,600 (13,400)

- Matthew Calbraith Perry—9,960 (49,000)

- John E. Fogarty—9,780 (28,700)

- John O. Pastore—9,650 (27,770)

- George Downing—6,720 (66,000)

- Zachariah Allen—5,530 (16,800)

- Nap Lajoie—5,400 (66,900)

- James Varnum—4,560 (8,210)

- Sissieretta Jones—2,960 (30,300)

- Edward Bannister—2,680 (15,500)

- Antoinette F. Downing—1,920 (3,280)