Last week, I gave you my list of the top twenty greatest Rhode Islanders of all time, numbers twenty through sixteen (as well as my honorable mentions and five current Rhode Islanders to watch). The following famous Rhode Islanders just missed my top ten, but still rank high. Next week I will give you numbers ten to six and the week after that numbers five to one.

Rhode Islanders can be proud of this top ten and twenty list. I am safe in saying that this list is more impressive than that of any other small or lightly populated state in the country, and is more impressive than many of the medium-sized and large states. Small state big history indeed!

I have made a few revisions to my Honorable Mention list; I set it forth below, as well as top current Rhode Islanders to watch.

At the end of this article is a brief explanation of the criteria I used.

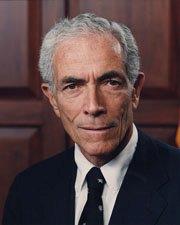

15. Claiborne Pell (1918-2009)

The patrician United States Senator from Rhode Island is best known for creating the college grant program for poor and middle class students that bears his name (the Pell Grant), but he also wrote the legislation that established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. He further pushed through legislation in 1966 to promote the responsible use and long-term development of America’s coastal and ocean resources, which ultimately led to, among other things, the creation of the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography. He was proud of his key role in spurring what is known as the Seabed Treaty, in which the U.S., Soviet Union and other countries agreed not to use nuclear weapons and other weapons in the ocean floors. A Democrat, he was widely regarded as the most formidable politician in Rhode Island history—in six victories over Republican opponents in U.S. Senate campaigns, he received an average of 64 percent of the vote. This despite President John Kennedy once calling him, jokingly, “the least electable man in America.”

Claiborne DeBorda Pell was born in New York on Nov. 22, 1918. Among his ancestors, one was the founder of the Lorillard Tobacco Company and five, including his father, Herbert Claiborne Pell, served in Congress. When Claiborne Pell was nine, his wealthy family moved to Newport, Rhode Island. He graduated from Princeton University and received a master’s degree in history from Columbia University in 1946. During World War II, he served in the Coast Guard in the Atlantic. After the war, he joined the Foreign Service. After participating in the 1945 San Francisco conference that drafted the United Nations charter, he became a staunch defender of the institution, often carrying a copy of the charter in his pocket. When he decided to run for the U.S. Senate in 1960, he defeated two former governors for the Democratic nomination. He was committed to maritime and foreign affairs issues, strongly in favor of abortion rights, a consistent vote for labor and an ardent advocate of arms control and the rule of law in international affairs. While always courteous, he could be aloof and diffident. His unwillingness to impose his agenda on others served him poorly, some thought, when he became chairman of the prestigious Senate Foreign Relations Committee after the Democrats regained control of the Senate in 1987. In 1991, he reorganized the committee and gave much of the work and funding to subcommittees. (I won a Pell Medal Award for U.S. History while attending South Kingstown High School in 1977, a program that Senator Pell sponsored at Rhode Island high schools and colleges for many years and continues today. After meeting him in Washington, D.C. later that year, I next met him at Brown University, after I organized a student aide event that he kindly attended as the main speaker.) In 1995, Time magazine dubbed him “Senator Oddball,” rehashing a 1987 incident when, fearing an extrasensory perception gap with the Soviets, he invited carnival-level spoon bender Uri Geller to Washington to demonstrate his skills. Senator Pell also attended a symposium on UFO abductions. Parkinson’s disease forced him to retire in January 1997 and he died at his Newport home in 2009. At his memorial service held at Trinity Church, he was fondly remembered in speeches by Senator Edward Kennedy, former President Bill Clinton, and vice-president elect Joe Biden. The Newport Bridge was renamed in his honor in 1992. For further reading, see G. Wayne Miller, An Uncommon Man: The Life and Times of Senator Claiborne Pell (UPNE, 2011).

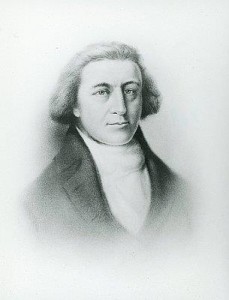

14. Robert Gray (1755-1806)

Born and raised in Tiverton, he descended from the prolific Gray family, which arrived in Tiverton in the seventeenth century. He learned to be a sailor there and is one of three Rhode Islanders on this list from its sailing heritage. During the Revolutionary War, he probably served as a low-level officer on privateers. As an adult he operated mostly out of Boston. Departing Boston in 1787 as captain of one of two vessels, he was the first American to reach what is now the west coast of the United States, when his fur trading ship arrived at Oregon in 1788. He traded for otter pelts with local Native Americans on the coasts of Washington and Oregon and then carried the pelts to sell at Canton, China, thus pioneering the American maritime fur trade in that region and opening a new market in Asia. On his way he stopped at the Hawaiian Islands, commanding the first American vessel to dock there. When he finally returned to Boston after three years, he became the first American citizen to circumnavigate the world. He returned to Oregon in 1792, where he entered the mouth of the Columbia River, which he named after his ship. His discoveries helped to secure the Oregon territory for the U.S. and to keep it away from British-controlled Canada. When he returned to Boston, he had circumnavigated the globe again. He died at sea of an unknown illness (possibly yellow fever) at the age of fifty-one. Other than by his surviving wife and four daughters, little notice was taken of his death, as his achievements did not become famous in his lifetime. Today six elementary and middle schools are named after him in Oregon and Washington, as well as several geographic points in that region. What you can see today: his homestead, a private home, at 3622 Main Road in Tiverton. For further reading: John Scofield, Hail Columbia! Robert Gray, John Kendrick, and the Pacific Fur Trade (Oregon Historical Society Press, 1992) and J. Richard Nokes, Columbia’s River, The Voyages of Robert Gray, 1787-1793 (Washington State Historical Society, 1991).

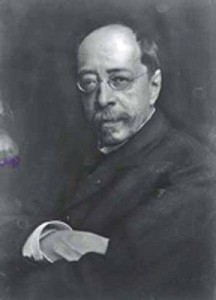

13. John La Farge (1835-1910)

John La Farge is best known for his innovations in stained glass design during the late 19th century, but he was also a skilled painter. Born in New York in 1835, after graduating from the Roman Catholic Mount St. Mary’s College in Maryland, at the age of 24, he went to Paris to study painting under Thomas Couture. La Farge returned to the United States in 1859 and settled in Newport, Rhode Island to begin his career as an artist. There, La Farge studied with American romantic artist William Morris Hunt, and became close friends with famous intellectuals William and Henry James. Then he fell in love with Margaret Mason Perry, granddaughter of Oliver Hazard Perry. After he finally convinced her to convert to Catholicism, the two were married at St. Mary’s Church in Newport in 1860. The family lived at various locations in Newport and on Paradise Valley in Middletown. His Newport paintings, in the 1960s, were considered “avante guarde” for their period, particularly ones of Paradise Valley he painted from 1866 to 1868. La Farge lived in Newport until around 1880, but his family always remained there. In 1876 La Farge was commissioned to design the interior of Trinity Church in Boston, Massachusetts. These murals and stained glass designs were greatly admired, leading to a number of important commissions for public buildings, including St. Thomas’s Church, New York (1878), the Church of the Ascension, New York (1888), and Memorial Hall at Harvard University. In 1880 he painted and fitted with stained glass windows for the Newport Congregational Church at 73 Pelham Street. He did private commissions for prominent patrons, such as making a stained glass skylight for Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York City, which was later moved to the Breakers in Newport. La Farge also worked in watercolor, and among his best-known watercolor paintings are those made during his travels, particularly those during his visit to the South Seas in 1890 and 1891. He wrote eight books and numerous essays on art. La Farge continued to produce art, write, and travel until he suffered a serious mental illness in the Spring of 1910, possibly resulting from his working with lead. He died later that year at Butler Hospital in Providence. What you can see today: his stained glass windows, murals and paintings are exhibited at art museums across the country, including the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and Rhode Island School of Design Museum.

12. Thomas Wilson Dorr (1805-1854)

Born in Providence into one of the state’s most prestigious families, Dorr spent most of his adult life supporting the extension of voting rights to landless white Protestant and Irish Catholic men, in an attempt to modernize and make more fair Rhode Island’s political system. In 1841, Dorr’s “People’s Constitution” granted universal adult white male suffrage, which was approved by popular vote but resisted by the conservative legislature. His creation of a parallel government drew both criticism and commendation on a state and national level. President John Tyler, although in the Democratic Party, failed to support him; some of Tyler’s powerful supporters from Virginia were concerned that the doctrine of popular sovereignty could be used to end slavery in the South. In May 1842, Dorr resorted to arms. After an abortive assault on the Providence armory, his government collapsed and he fled the state. Governor Samuel King declared martial law, arresting many of his followers. In late June of 1842, Dorr once again attempted to resurrect his government in the small village of Chepachet in northwest Rhode Island, but a strong army loyal to Governor King easily dispersed his followers, with Dorr fleeing the state once more. While progress in expanding voting rights was eventually made in a new 1843 state constitution, Dorr suffered the consequences of his efforts. Returning to the state, he was charged with treason, and in 1844 was convicted at a rump trial in Newport and sentenced to solitary confinement and hard labor for life. Democrats across the nation decried the incarceration—the northern Democratic slogan for the 1844 presidential election was “Polk, Dallas, and the Liberation of Dorr.” Dorr was released from prison in 1845, but after spending a year in a dank Providence jail in solitary confinement his health was broken. With state voters electing his allies, Dorr’s civil rights were restored in 1851 and his conviction was set aside in 1854. Remaining in poor health, he died at the age of forty-nine and was buried at Swan Point Cemetery. What you can see today: the Dorr Rebellion website, hosted by Providence College, and maintained by Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone (search in Google for “Dorr Rebellion” and “Providence College” and click on “Dorr Rebellion Project Page”). For further reading: Erik Chaput, The People’s Martyr. Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion. (University of Kansas, 2013).

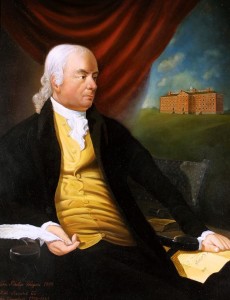

11. Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785)

Born in what is now Scituate, he was apparently self-taught, becoming a judge on the court of common pleas and then selected as Speaker of the House in the General Assembly. In 1742, he moved to Providence and resided in his house at the corner of Hopkins and Benefit Streets for the remainder of his life. In 1754, as a delegate to the Albany convention in New York, he supported Benjamin Franklin’s early plan of union. About the same time he helped to establish what would become Brown University and Providence’s first library. He was the leader of the Providence faction opposing Samuel Ward and his Newport faction in what became known as the Ward-Hopkins controversy that rocked Rhode Island politics in the 1750s and 1760s. Hopkins and Ward traded the governorship numerous times. Hopkins spoke out against what he saw as British tyranny in the 1760s and in 1764 he wrote an influential pamphlet, “The Rights of the Colonies Examined,” attacking the Stamp Act and Sugar Act. He authorized gunners posted at Fort George, on what is now Goat Island off Newport, to fire cannon at the British navy eight-gun schooner St. John on July 9, 1764, in order to protect Newport’s smuggling industry. These were the first shots in resistance to British authority in America leading to the American Revolution. As Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the colony, he helped to quash attempts to identify the perpetrators of the 1772 burning of the British revenue schooner Gaspee. He attended the first Continental Congress in 1774, and later signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Wearing a distinctive hat in John Trumbull’s famous painting of the signers, his signature was famously shaky, as he suffered from palsy. He said at the signing, “My hand trembles, but my heart does not.” At age 69, he was the second oldest signer, one year behind Franklin. In Congress, he helped to establish the Continental Navy and arranged for his brother, Esek, to serve as its first (and only) admiral. Departing Congress in 1778 due to bad health, he continued to serve on the state’s war committee. He died in 1785 at the age of 78 and is buried at the North Burying Ground. What you can see today: The Governor Stephen Hopkins House at 15 Hopkins Street on College Hill is open to the public. For further reading: Marguerite Appleton, Portrait Album of Four Great Rhode Island Leaders (Rhode Island Historical Society, 1978) and Patrick T. Conley, Rhode Island’s Founders: From Settlement to Statehood (History Press, 2010) (both are available at the Rhode Island Publications Society).

[Banner Image: “Paradise Valley,” set in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, by John La Farge in 1868 (Private Collection)]

Honorable Mentions (in Alphabetical Order)

Here are fifteen great Rhode Islanders who just missed making my top twenty list but still deserve honorable mention:

- Edward Bannister (1828-1901) of Providence, nationally respected African American painter of pastoral scenes

- Moses Brown (1738-1836), influential Quaker abolitionist and philanthropist from Providence, who also hired and financed Samuel Slater

- William Ellery Channing (1780-1842), influential Unitarian minister in Boston, born and raised in Newport

- George Corliss (1817-1888), inventor of an advanced steam engine, a marvel of its day

- Antoinette Downing (1904-2001) of Providence, influential in the historic preservation movement in the twentieth century

- Mary Dyer (1611-1660), early pioneer in Portsmouth and Newport who was executed by Puritan authorities in Boston in 1660 for refusing to renounce her Quaker beliefs

- George Downing (1819-1903), African American civil rights leader from Newport

- John Goddard (1723-1785) and John Townshend (1732-1809), Newport colonial cabinetmakers whose distinctive pieces with a Quaker-inspired plainness today sell for millions of dollars

- Theodore Francis Green (1867-1966), from Providence, who when he became state governor in 1935 helped to end the stranglehold of Republican rule and later served as U.S. Senator from 1937 to 1961

- Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803), influential Congregationalist minister in Newport and early abolitionist

- Napoleon (Nap or Larry) Lajoie (1874-1959), Hall of Fame baseball player from Woonsocket

- Royal Little (1896-1989), founder of Textron Inc. and pioneer of the idea of conglomerates (one company acquiring diversified businesses)

- James Mitchell Varnum (1748-1789), Revolutionary War general from East Greenwich, who was appointed a federal judge in the Northwest Territory and was an early Ohio pioneer

- Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones (1868-1933) of Providence, one of the great singers of the late 1800s and early 1900s who was the first African American women to sing at Carnegie Hall and performed at the White House for four Presidents

Current Rhode Islanders to Watch (in Alphabetical Order)

Here are five Rhode Islanders in the prime of their careers who one day may move up to my honorable mention list or top twenty list:

- Elizabeth Beisel of North Kingstown, Olympic and World Champion medalist in women’s swimming events

- Viola Davis of Central Falls, multiple award-winning movie, television and stage actress (African American)

- Jhumpa Lahiri Indian American acclaimed novelist who moved to the state when she was two and attended the University of Rhode Island

- Gina Raimondo of Smithfield, the state’s first elected female governor

- Dr. Rudolph E. Tanzi of Cranston, Harvard University professor leading a major effort researching Alzheimer’s disease

Criteria Used for Selections

This part explains in part the criteria I used in making my selections for my top twenty list of the Greatest Rhode Islanders of All Time.

First of all, I give the most weight to Rhode Islanders who made the greatest contribution at the national level and lesser weight to their contributions to Rhode Island. If my list was of Rhode Islanders who had the greatest impact on Rhode Island, Gilbert Stuart, among others, would not be on the list, while Thomas Wilson Dorr would probably be ranked second, and Dr. John Clarke, Theodore Francis Green, Woonsocket’s Aram Pothier, and historic preservationists Antoinette Downing and Doris Duke, among others, would be on the list.

Second, I had to define who is a Rhode Islander. I included those who were born and raised in the state, and those who moved to the state and lived in it during their periods of notable accomplishments. For example, I included Gilbert Stuart, who was born in North Kingstown and trained as a painter in Newport until he was fifteen years old (and returned to Newport for a short stint later). But I excluded George M. Cohan, who was born in Fox Point in 1878 of parents who were itinerant travelling entertainers and who left the state after he finished second grade. If I had included those simply born in the state, Cohan, the composer of favorites such as “Over There,” “Give My Regards to Broadway,” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” would have been in my top ten.

One feature of my top twenty list that jumps out is that, with the exceptions of Metacomet and Julia Ward Howe, each person listed was a white male, and all but four of them were Protestants (the other four were Catholics). The fact is that for most of our state’s and nation’s history, women were not allowed or encouraged to achieve greatness, but were largely relegated to the domestic sphere; and persons of color, and for much of our history, persons of different religions and ethnic backgrounds, suffered from discrimination. During most of our country’s early history, when this discrimination was at its worst, it was easier for men to accomplish a “first” and become famous. This is one of the products of discrimination: preventing talented individuals who could become great on a national level from becoming great on a national level.

There are certainly plenty of accomplished Rhode Island women and persons of color and ethnic and religious backgrounds to make up more top ten lists, which I plan to do in the future. The brilliant Puritan dissident Anne Hutchinson would have appeared on my top ten list, but I decided that she did not have a sufficient connection to Rhode Island to be considered a Rhode Islander. Her famous trial occurred when she was a Massachusetts resident. She moved to Portsmouth in April 1638 to join her supporters there and became one of the town’s founders, but so was William Coddington. After her husband’s death, Anne left Rhode Island in the summer of 1642 for Dutch-controlled New York and was killed by Indians there the next year.

Considering the historic discrimination against African Americans in the state and country, it is impressive that two of them achieved “honorable mention” status on my list. Interestingly, on my “current five Rhode Islanders to watch” list, four are women and there is substantial diversity.

After my fourth and last article in this series, I will share with you several lists that I prepared and relied in part in making my selections.