The following are my top ten turning points in the history of Rhode Island. You may differ with some of my choices, but that is part of the fun.

- Founding of Rhode Island, 1636. Foundings are always important, and Rhode Island’s was no exception. In 1636, two Puritan colonies with deep English roots, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut, dominated white New England. With his radical religious views sharply conflicting with conservative Puritan practices, the minister Roger Williams found himself facing banishment. Williams fled to the area of what is now Providence. What would one day become the colony and later state of Rhode Island had not yet been settled by whites, primarily because it was then dominated by two tribes, the Narragansetts, with its historic lands in the southern part of Rhode Island, and the Wampanoags, then centered on Bristol Neck and to the east. Fortunately for Williams, he was welcomed by local Native Americans, and he would later frequently serve as an intermediary between them and Puritan authorities in Boston and Pilgrim authorities in Plymouth. Williams paved the way for other white settlers with so-called heretical religious views, including Samuel Gorton who settled Warwick in 1642, and Ann Hutchinson, William Coddington, and John Clarke, who settled Aquidneck Island in 1638. This resulted in the initial name of the colony being the colony of Rhode Island (i.e., Aquidneck Island) and Providence Plantations. The Baptist sect was first established Providence in 1639.

- The Rhode Island Charter of 1663. Dr. John Clarke of Newport was able to secure Rhode Island’s existence as a separate colony and prevent it from being gobbled up by her stronger neighbors, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut, by obtaining in England a charter from King Charles II. The charter of 1663 also brought Rhode Island’s feuding towns under one system, fixed its boundaries, and, uniquely, made her a “lively experiment” where freedom of religion could be practiced by Baptists, Quakers, and other nonconformist Protestant sects, and eventually, Jews and Catholics. This development was to the great chagrin of the Puritans who had created a system based on the established Puritan (later Congregational) Church. The policy of religious liberty would later be embedded in the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution. The charter also granted the colony democratic freedoms that in colonial times made Rhode Island one of the most democratic jurisdiction in the world. Its percentage of white adult male voters was high for the times, and Rhode Islanders voted for governor and General Assembly delegates twice a year. Rhode Island was one of only two of the original thirteen colonies lacking an appointed Royal governor. The Charter of 1663 lasted until 1843.

- The Great Swamp Fight, 1675. The outbreak of what became known as King Philip’s War began modestly in 1675 when Metacom, or King Philip, the chief of the Wampanoags, with his seat at Mount Hope in what is now Bristol County, violently reacted to a series of humiliations suffered at the hands of Plymouth authorities. Soon most of New England was a battleground, and the desperate struggle raised the question of whether the white settlers in New England would be pushed back to an area around Boston or whether the Native Americans would fall under the domination of white authorities forever. Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut authorities decided that the neutrality of the strongest tribe in southern New England, the Narragansetts, could not be assured and that a preemptive strike against them was their best strategy. Putting together a relatively small invasion force armed with muskets, the brutal winter conditions made marching difficult, but also made it possible for the army to penetrate usually impassable swamps and locate the Narragansett’s unfinished palisade fortress deep in the Great Swamp, several miles from what is today West Kingston, in the town of South Kingstown. On December 16, 1675, striking at the unfinished part of the fort, after a short but fierce firefight with Narragansett warriors, the invaders set fire to wigwams, which soon led to a scene of burning and devastation. The ensuing fire killed hundreds of Indians, including many women and children, and destroyed the tribe’s winter food supplies. Some soldiers then questioned the ethics of killing women and children, and some historians today call it a massacre. In revenge, despite white Rhode Islanders’ decent record of dealing fairly with Indians, Narragansett warriors burned practically every white structure on the mainland of Rhode Island, not even sparing Roger Williams’s small settlement at Providence (though they did not kill him or his followers). Most white Rhode Islanders fled to the safety of Aquidneck Island. In March 1676, the chief sachem of the Narragansetts, Canochet, led a large party that ambushed and killed about sixty-five whites and twenty of their Indian allies near what is now Central Falls, but Canonchet was captured and killed several days later. When Connecticut forces from the New London area made a series of raids into southern Rhode Island, the power of the Narragansetts was permanently broken. With the killing of King Philip in a swamp near Mount Hope, on August 12, 1676, by a party commanded by Captain Benjamin Church of Little Compton, the war ended and the rebuilding of mainland Rhode Island by white survivors began. With the defeat of the Narragansetts, the southern part of the state was opened for white settlement.

- The Burning of the Gaspee, 1772. For nearly one hundred years, Rhode Island merchants from Newport, Providence, Bristol and other smaller ports plied their maritime trade with little oversight from Royal authorities in distant Great Britain. What rules were in place were typically ignored and smuggling became common. The General Assembly kept maritime restrictions and taxes to a minimum. Rhode Island gained the dubious distinction of dominating the slave trade among the original thirteen colonies (though colonial American ships overall carried a small percentage of African slaves). When finally in the 1760s Great Britain began to tighten its maritime trade rules and impose duties and taxes, and to send Royal Navy ships to enforce the new rules, Rhode Island merchants and sailors naturally resisted. In the night of June 9-10, 1772, matters came to a head, when news arrived in Providence of the Royal Navy schooner Gaspee, which had been vigorously enforcing navigation laws in Narragansett Bay, had become stuck on a sand bar on Namquit Point near Warwick. A small party of men, led by prominent Providence merchant John Brown and one of his ship captains, Abraham Whipple, departed in small boats and approached the stricken vessel, shot and wounded its captain, and then burned it. Outraged Royal authorities could never obtain any credible witnesses against the raiders, despite their concerted efforts. After this spectacular event, it was not far for Rhode Island to become the first colony to declare its independence from Britain on May 4, 1776, two months prior to the Continental Congress sitting in Philadelphia making its declaration on behalf of all of the thirteen colonies. During the war, the British army and navy occupied Newport, then one of the five top ports in North America, and the rest of Aquidneck Island, as well as Conanicut Island (Jamestown), from December 1776 to October 1779. Patriot authorities controlled the mainland and the new state’s government. In August 1778, an allied French and American force failed to capture Newport from the British, but the American army fought effectively at the Battle of Rhode Island, led by a regiment consisting mostly of freed Rhode Island slaves. From July 1780 to September 1781, a French naval and army expeditionary force occupied Newport, when it helped to win the Revolutionary War at Yorktown, Virginia. Newport never reestablished itself as one of North America’s key seaports.

- Rhode Island Joins the United States, 1790. Rhode Island showed its independent streak by not only being the first of the thirteen colonies to end its allegiance to the Crown, but by also being the last of the thirteen colonies to join the new United States. Rhode Islanders feared being dominated by larger states and worried that a central government would directly tax them. The rural party then dominated state politics and, led by Jonathan Hazard, supported the controversial policy of issuing paper money that could be used to repay wartime and other debts. In a 1788 popular referendum, ratification lost by 2,708 to 237, which was lopsided even taking into account a Federalist boycott of the vote. After the General Assembly then rejected numerous calls to convene a ratifying convention, one was finally held at Little Rest in South Kingstown in March of 1790, but the delegates failed to ratify the U.S. Constitution. Under the threat of being treated as a foreign country and having its exports taxed accordingly, and possibly of being gobbled up by Massachusetts and Connecticut, or having Providence secede, Rhode Island delegates, meeting at Newport on May 29, 1790, finally adopted the U.S. Constitution by the narrow vote of 34 to 32.

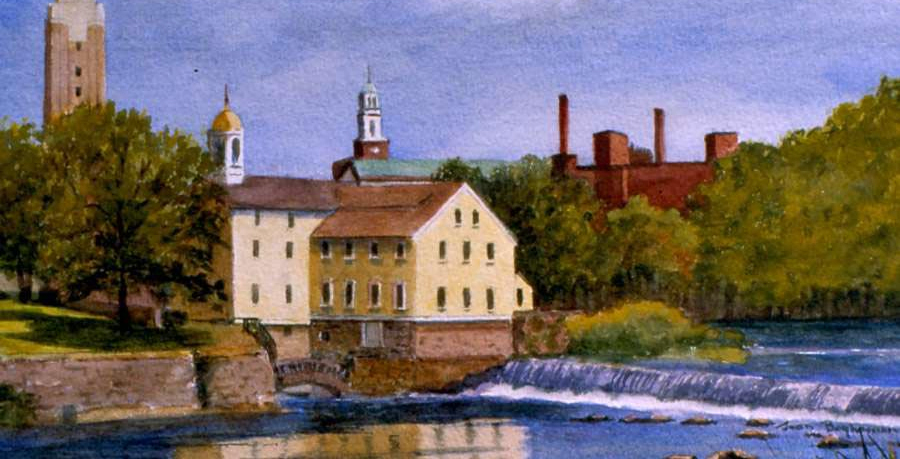

- Samuel Slater Establishes a Factory at Pawtucket, 1793. In 1789, Moses Brown engaged English immigrant Samuel Slater to establish a new textile mill powered by the running waters of the Blackstone River. Slater knew the technological secrets of cotton spinning machinery and managing mills after working for six years at the most modern textile mills in England. Slater’s success at Pawtucket starting in 1793, at what is now called the Slater Mill historic site, ushered in not only the state’s, but the country’s, age of industrialization. Soon mechanized textile mills dominated the Blackstone River Valley in the northern part of Rhode Island. Many of their first employees were women escaping the drudgery of farm work and seeking more personal independence, but they were then joined by child laborers and low-wage immigrants, many fresh from Ireland. In South County, woolen mills, including those owned by the Hazard family, produced kersey or “slave cloth,” which was used to clothe slaves in the South. These small family concerns were the forerunners of larger industrial enterprises that came to employ many Rhode Islanders by the mid-to-late nineteenth century, such as B.B. & R. Knight Company, which owned and operated eighteen textile factories throughout the state, including the largest mill in America at Natick (West Warwick). The founding of the American jewelry industry by Nehemiah and Seril Dodge helped make Providence one of the chief industrial cities of New England by the 1820s. In Providence, the Corliss steam engine was invented and manufactured at the country’s largest steam engine factory, and Brown and Sharp rose to become the country’s largest producer of precision tools, and it manufactured sewing machines used to produce uniforms and tents for the Union Army during the Civil War. The large numbers of factories and their workers in Rhode Island spurred improvements in transportation, including railroads, steamboats, and streetcars.

- The Dorr War, 1841-1842. Following the American Revolution, many states updated their constitutions, reducing restrictions on voting by white males (and in some cases black males). Rhode Island kept, however, its Charter of 1663, which not only required a minimum ownership of land to vote, it allowed the rural part of the state to dominate politics. Under the charter, the House of Deputies had to consist of six deputies from Newport, four each from Providence, Warwick and Portsmouth, and two from every other town. While this apportionment made sense in colonial times, in no longer did in a changed Rhode Island. For example, in the General Assembly, the small town of Exeter was entitled to two deputies, the same as the burgeoning towns of Pawtucket and Cumberland. Tensions rose as more and more landless white males moved from their farms to more urban areas to work in textile mills and city jobs such as firemen, policemen, and tradesmen. Landholding conservative elements in the state also became increasing concerned about rising numbers of Irish immigrants and what they viewed as their strange Roman Catholic religion. Suddenly, Rhode Island had become the least democratic state in the Union. Thomas Wilson Dorr, a scion of an east side Providence family, took over leadership of a reform movement and organized an extralegal vote to adopt a more liberal constitution in December 1841, under which he was voted in as its first governor in March 1842. Facing strong conservative opposition, matters came to a head on May 18, 1842, when Dorr tried to rally his dispirited supporters and seize the Providence armory by force. When that attempt failed, Dorr fled the state, only to return later in June to hold a People’s Legislature at Chepachet. When an army of 2,500 marched to Gloucester, Dorr’s movement fell apart and Dorr fled the state a second time. Returning in October 1843, Dorr was tried for treason, convicted and jailed. In 1843, a new state constitution liberalized voting rights to some extent, including extending the suffrage to black males, but some undemocratic features remained. In an anti-Irish immigrant measure, naturalized males still needed $134 of property to vote (this rule was not eliminated until 1888); and rural control of the state senate was retained (each town was entitled to one senator).

- Immigration, 1880-1930. Between 1880 and 1930, hundreds of thousands of immigrants flowed into Rhode Island, changing its character forever. Many sought to improve their economic plights by leaving their homelands of French Canada, Ireland, England, Scotland and Germany. By the 1920s, new immigrants from Italy, Portugal, Poland and the Azores arrived. These immigrants were drawn by jobs in the burgeoning industrialized economy of Rhode Island, led by Providence firms such as Brown and Sharpe, Gorham Manufacturing Company (the country’s premier silverware manufacturers), and the American Screw Company (one of the country’s largest manufacturers of screws), and Woonsocket’s National Rubber Company (one of the country’s largest rubber boot manufacturers, owned by Irish-American Joseph Banigan). Many of the Italian, Portuguese and Azores immigrants arrived at the port of Providence on the legendary Fabre Line and stayed; others wound up in neighboring small cities such as Cranston and Warwick. Urban neighborhoods of Irish, Italian and French Canadian immigrants arose. Eventually, Rhode Island had the highest percentage of immigrants of any state in the country, and by 1905 it became the first (and still is the only) state in which Roman Catholics were the majority. Catholic churches, schools and charitable institutions were established in urban areas, and Bishop Mathew Harkins (1887-1921) served as an effective prelate.

- The Revolution of 1935. From the Civil War to the 1920s, the Republican Party, dominated by the traditional Protestant elite, was able to control state politics, despite the growing numbers of immigrants. Using tough campaigning and sometimes corrupt practices, political bosses such as Charles R. Brayton kept a firm grasp on political control of the state. Their power was aided by the state’s constitution, which continued to favor the conservative, rural parts of the state, even as they faded into a small feature of the state’s economy. By 1910 Providence and the six large factory towns around it had two-thirds of the state’s population, but twenty-two small towns with populations of fewer than 5,000 controlled the state senate. By 1935, spurred by the ongoing Depression and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and led by Governor Theodore Green, a broad state coalition of foreign born, Catholics, labor unions and blacks allowed the Democratic Party to seize control of state government branches. Finally, the sons and grandsons of immigrants would become key political leaders in the state, starting with Irish-Americans, and later including Italian-Americans and other ethnic nationalities. The dominance of Democrats in the state General Assembly permitted the balance of power to shift from employers to employees, and from the rural parts of the state to Providence, but as a result of creating what has (again) effectively been a one-party state, periodic scandals and corruption have arisen and Democratic politicians arguably have gone too far in favoring their supporters.

- The Departure of Nicholson File Company, 1959. In the early 1900s, Rhode Island’s manufacturing-based economy peaked and thereafter suffered a steady decline. While at the turn of the twentieth century Rhode Island was the home of dozens of thriving factories employing tens of thousands of workers, by the end of the century most of them had either shut their doors or moved out of state. Even the state’s jewelry industry, once the pride of Rhode Island, has declined. The causes of the departures and decline were due to national and worldwide economic forces beyond the state’s control. The state fell victim to the economic reality that businesses can move to other states or even countries, to find lower-wage workers and to avoid what they believe are onerous state and local laws, even if such laws are viewed objectively as fair. The departure of Nicholson File Company from the state in 1959 typified this trend. Started in Providence in 1864, the Nicholson File Company became one of the country’s premier manufacturers of files and rasps, including jeweler’s files with as many as 300 teeth to the inch. While the company established plants in various states, its main manufacturing plant was located in Providence. An image of it in 1889 shows that the plant covered an entire city block, and another 1954 image shows the same. But in 1959, the company shut down its Providence plant and moved the operations to Anderson, Indiana, and it moved its administrative headquarters to East Providence. In 1972, the company was acquired by Cooper Industries, thus ending the existence of another long-established Rhode Island manufacturing company. The population of the state’s dominant city, Providence suffered from such moves—it fell from 248,674 in 1950 to 179,116 in 1970, the largest outmigration of any major American city during that span. Today, while the state’s economy has had some success in the areas of education, health care, tourism, and a combination of new and traditional businesses, Rhode Island still lags behind most states in key economic indices, such as the rate unemployment.

Other key turning points: Roger Williams obtains Rhode Island’s first charter, 1643-44; long and stable governorship of Samuel Cranston, 1698-1727; King settles colony’s boundary disputes, adding the towns of Cumberland, Barrington, Bristol, Warren, Tiverton, and Little Compton on its eastern boundary and securing the western boundary with Connecticut, 1747; law gradually emancipating slaves enacted, 1784; Providence overtakes Newport as a commercial maritime port, 1790s; Vanderbilt mansion constructed in Newport, which becomes a playground for the eastern elite, 1895; right of women to vote for President, 1917; the reduction of the Navy’s presence and historic renovation in Newport, 1970s; renewal of commercial areas of Providence, including the opening of its waterfront, 1980s and 1990s; and various financial and political scandals, 1980 to the present; election of Gina Raimondo as state governor, the first woman to hold the position.

Most of my top ten selections are from the state’s early history. I think that is because my selections relate to what makes Rhode Island unique, which tended to be in its early years. For example, the impact of the Civil War, World War I and World War II were felt deeply by state residents, but not in a unique way compared to other states. An another example, the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of all U.S. women to vote, which was a tremendous development in Rhode Island, as it was in most other states.

Most of my top ten selections are from the state’s early history. I think that is because my selections relate to what makes Rhode Island unique, which tended to be in its early years. For example, the impact of the Civil War, World War I and World War II were felt deeply by state residents, but not in a unique way compared to other states. An another example, the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of all U.S. women to vote, which was a tremendous development in Rhode Island, as it was in most other states.

For two other views on the state’s top ten turning points, see William G. McGloughlin, “Ten Turning Points in Rhode Island History,” and J. Stanley Lemons, “Rhode Island’s Ten Turning Points: A Second Appraisal,” in Rhode Island History, vol. 45, no. 2 (May 1986), pp. 41-55 and 57-70