There were probably more changes in shipping in the 19th and early 20th century than the world has ever known. Since the home my father, Captain Halsey Chase, built at Homestead on Prudence Island commanded a view of the entire east and north portions of Narragansett Bay, we didn’t miss much that was nautical.

Although the American clippers were at the height of their glory between 1830 and 1860, there were still a few in service when I was a child. It was a rare sight to see one speeding up the bay with all sails set. The name “clipper” was derived from “going at a good clip” or “clipping time from previous records.” Oak and teak were used in the construction of those early crafts — the latter, because of its oily nature, could resist water and weather. When metal replaced wood for hull construction about 1856, teak was still used for decks and fittings. The iron and steel hulls reduced the danger of fire hazards, which were always a problem with wooden ships.

Donald McKay of Boston was a master builder of clipper ships. Because of the expanding tea and wheat trade, and the California gold rush of 1848, his designs were planned for speed rather than tonnage capacity. His famous Flying Cloud broke the speed record twice by making the trip to San Francisco in 89 days.

Those gay ships can best be remembered for their use in the East India and China Trade. Chests made of camphor wood or mango with brass locks and hinges were to be found in many homes. Living rooms were adorned with Tibetan rugs, ormulu clocks, Chinese export ware and crystal chandeliers. Mothers told their daughters how they had stood upon the widow’s walks of their homes watching for the return of the clippers from distant voyages.

Figureheads were often used on the bow of clippers to symbolize the ship’s name. The Great Republic, the largest wooden clipper, used an enormous eagle under the bowsprit. The Red Jacket had an Indian chief in feathered headdress. The, Lightning used a young woman whose long hair and drapery were artistically designed. The famous Flying Cloud used an angel blowing a trumpet. A fan-shaped shell and a dolphin were also popular figureheads.

The post-war American designers built medium clippers that were more functional. Construction of these “Down Easter” schooners was almost completely of Maine woods. The frame, stem and stern posts were of white oak; the planking and deck beams of pitch pine. They were seaworthy and fast enough to compete with the steadily growing steamer fleets. They, mainly, hauled grain from California to the East Coast.

The growth of the coal trade after 1870, especially in Taunton, Massachusetts, created a demand for larger vessels; therefore, the schooner era began. Of the sixty-eight four-masted schooners built in Maine between 1880 and 1889, ten belonged to Taunton, and Rhode Island owned five (three were from Providence and two from Newport). Many of them had Indian names: such as Pocahontas, Tecumseh and King Philip. Gradually the schooners became five and six-masted by 1900. It was a -thrilling sight to watch them sail by Prudence Island with their cargoes of coal, a fuel that was so necessary in every household when I was young. Most American schooners had a horseshoe nailed to their bowsprits with the open end upward to “keep the good luck from running out.”

The four-masted schooner Hope Sherwood in icy water. Launched in 1903, it was 172.8 feet long and had a breadth of 36.6 feet (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

In winter the crews on the coal schooners faced great hardships, for their decks were never free of water in rough seas. In zero weather, they would enter the bay with decks and rigging absolutely encased in ice from the frozen spray. Sometimes tugs would be able to plunge through the ice in order to, open a channel for the schooners before they could proceed up the bay to Providence with their cargoes. In 1917-18 the bay was completely closed for several weeks because of the ice.

The Jessie H. Freeman, a three-master commissioned in 1883, had an auxiliary coal burning steam engine but relied upon her sails mainly. She and the Lorenzo Jones imported fruit for the United Fruit Company.

The Thomas W. Lawson was the only seven-masted schooner ever built. She was constructed entirely of steel in 1902. Because of her size, she was unwieldy and a failure in the coal trade, simply because she was too deep to load a full cargo of 11,000 tons at any port except Newport News. Unfortunately, she capsized in a hurricane off the Isles of Scilly in 1907 and all of the crew were lost except the captain and an engineer.

The war of 1914 gave schooners a new impetus; but by 1920, they were unable to compete with steamboats. The Edna Hoyt was a five-master still in operation until 1938 when she was destroyed on the rocks off the Azores.

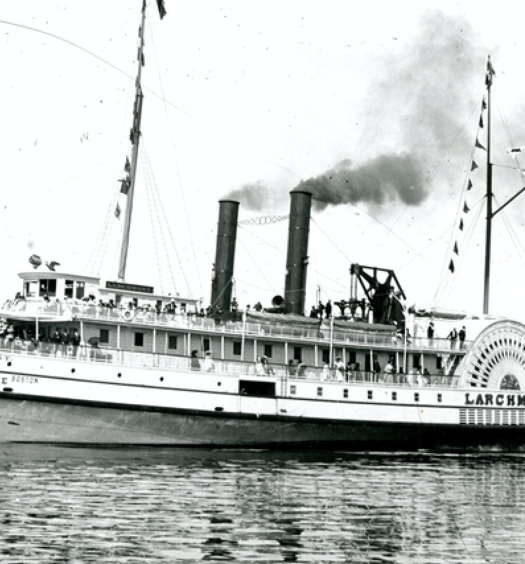

The steamship SS Chauncey M. Depew, owned by the Block Island, Newport and Providence Transportation Co., with passengers visible on all three levels (Providence Public Library)

Powerful ocean tugs would leave their coal barges moored off Prudence until a smaller tug came down from Providence for the final trip up the bay. Once my father took my sisters and me out in his rowboat to visit an empty barge that was waiting for an ocean tug to continue its journey. The crew greeted’ us in a friendly way and put down a rope ladder so that we could climb up for a visit. It was pretty scary climbing such a long ladder, but we made it safely and were served doughnuts and coffee in the immaculate galley by the captain. Descending the ladder was even more hazardous; however, it was an experience that I never forgot.

Fishing was a popular sport as well as an industry in those early days. It was especially interesting to watch the men in the menhaden boats lower their nets in a circle around a school of those oily fish. They would gradually decrease the size of the circle until the flapping fish were secured in the net and lifted to the deck.

Of course, the greatest thrill on Prudence Island was to see the Old Fall River Line boats go down the bay in winter when they were brilliantly lighted. We always watched them until they disappeared from sight on their way to Newport and New York. On a calm night in summer, we could even hear the orchestra playing as they sailed by. We often lighted huge bonfires on the shore for the ship would be sure to respond with a salute of three long toots of her whistle.

When I was eight years old, my father announced that we were going to New York. What excitement! My twin sister and I wore the new red dresses that our Mother had made with matching felt hats. We drove to the North End of the island in our democrat wagon and a friend took us to Fall River in his boat where we boarded the Priscilla. We had dinner in the gay saloon and admired the gold carpet and the beautiful columns and corned ceiling decorated with gold leaf. The orchestra played until midnight.

We didn’t get much sleep, because every time the fog horn blew, my older sister tried to echo the sound. At four a.m., we were on deck to view the bridges and the skyline of the big city. It was a spectacular sight even though the Flatiron and World buildings were the tallest at that time.

After we landed, we walked along the waterfront on old South Street. The jibbooms of schooners and some square riggers were projecting, over the street as cargoes were being unloaded into wagons. Drays clattered along the cobblestoned street transporting produce to the Farmer’s Market. It was a busy scene that is still vivid in my memory.

It was a great treat to go to Providence on a Saturday on the old City of Newport, which was a steamer with a walking beam. When we reached the big city, it was fun to watch the crew unload the produce that had been sent to the markets. The harbor would be filled with boats of every description for the sailing crafts were still in use until about 1920. I can remember the thrill of shopping in the Arcade. It was also fun to ride on the trolley car.

The sad part of the trip was to be left on the west side of the island at Prudence Park on the return trip. I would watch the lights of the steamer as long as I could; then, shedding a few tears, climb into our wagon for the two-mile ride to the east side of Prudence where our home was located. I longed, even then, for the life and gayety of the city.

Now, from our second floor apartment on Arnold Street, I enjoy watching the huge oil tankers and an occasional cruise ship as they enter Providence Harbor. Of course, they must wait for the powerful tugs that are still in use to maneuver them into, or out from, the docks. They even blow farewell toots as they leave the vessels, just as they used to when they left the old barges off Prudence Island.

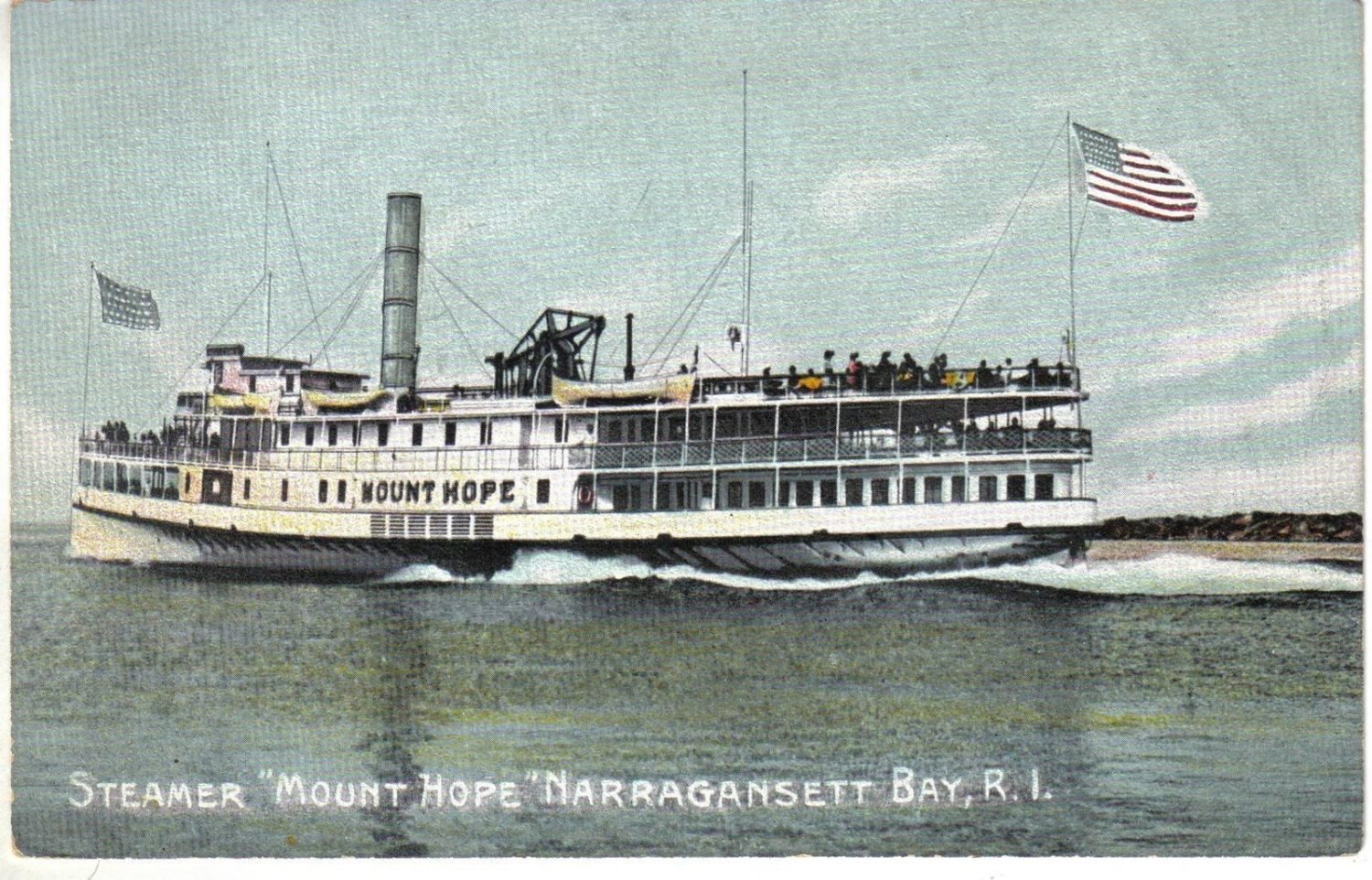

[Banner image: The steamboat Mount Hope in Narragansett Bay (Sandy Neuschatz Collection)]